By Laura Elliott

Honor. Duty. Acts of kindness. Extending benevolence to soldiers on the opposite side.

Incidents reflecting these noble traits were documented by the men who performed them, by those on the receiving end of aid, and by those who bore witnesses to such events. A few became iconic stories of the Civil War. Others are lost in time.

One of the forgotten stories is told here. It involves two captains: Benjamin Franklin Crabb of Iowa and Isaac Wheeler Avery Jr., of Georgia. Captured early in the war, both were exchanged and went on to make colonel. Details of their lives and how they intersected, scattered across time in various documents, are reassembled and recounted here.

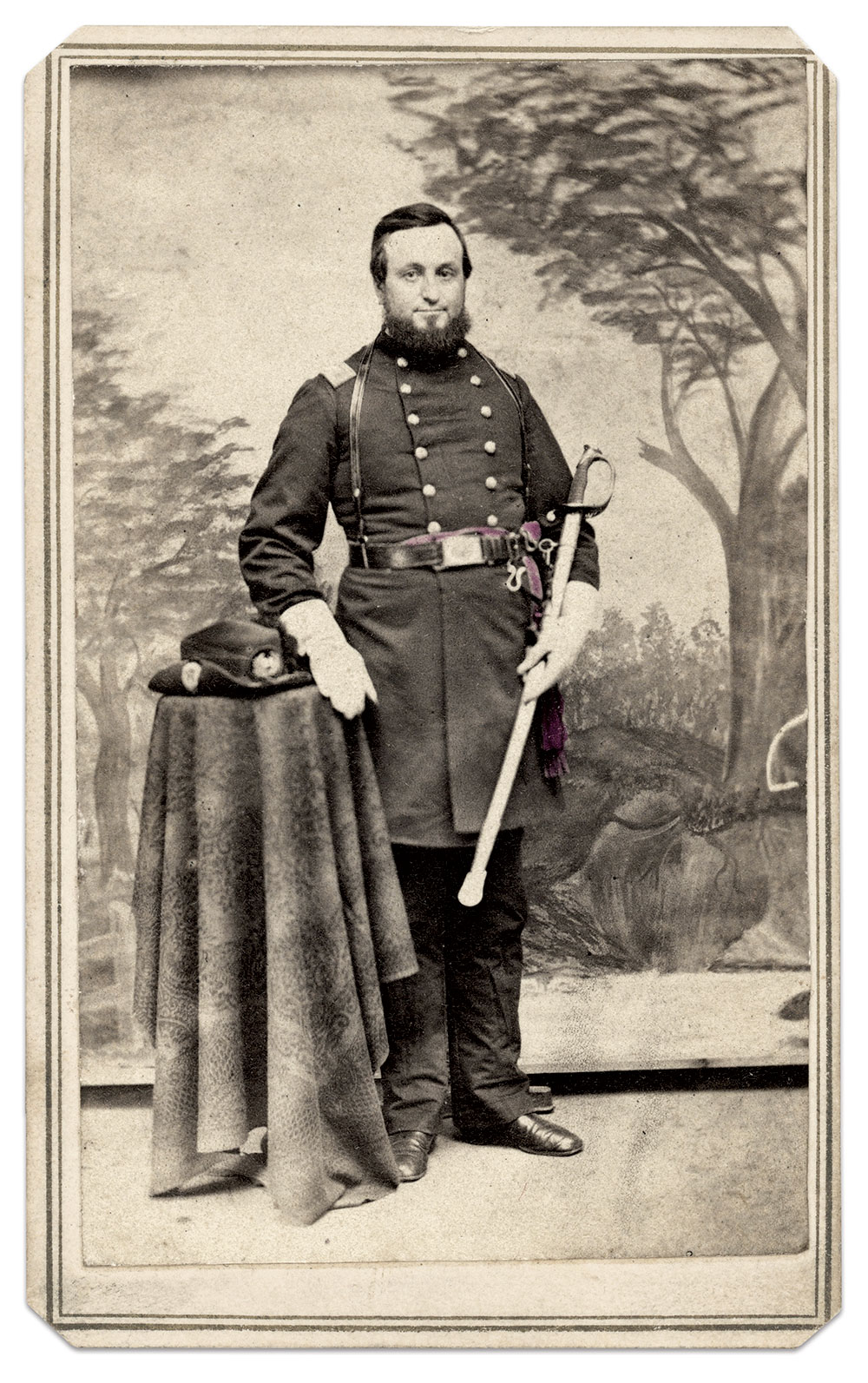

Commended for valor at the Battle of Belmont, where he was captured Nov. 7, 1861, peacetime hotel owner and Ohio native Benjamin Crabb served as the original captain of Company H, 7th Iowa Infantry. After falling into Confederate hands, Crabb’s captors transported him first to Memphis, Tenn., and then to Tuscaloosa, Ala. During this time, he sent at least two letters to his wife, informing her that he was well treated. He also asked her to have friends write to the commanding Union general, Henry W. Halleck, and lobby for his exchange.

Meanwhile, Confederates moved the Iowan to the prison camp at Macon, Ga. In June 1862 he gained his release, ending an eight-month stint in captivity. Crabb returned to his regiment, and was later promoted to colonel and the command of the 19th Iowa Infantry. He survived the war and returned to Washington, Iowa, where he resumed management of The Iowa House Hotel. He eventually settled in York, Neb., where he died in 1906 at age 85.

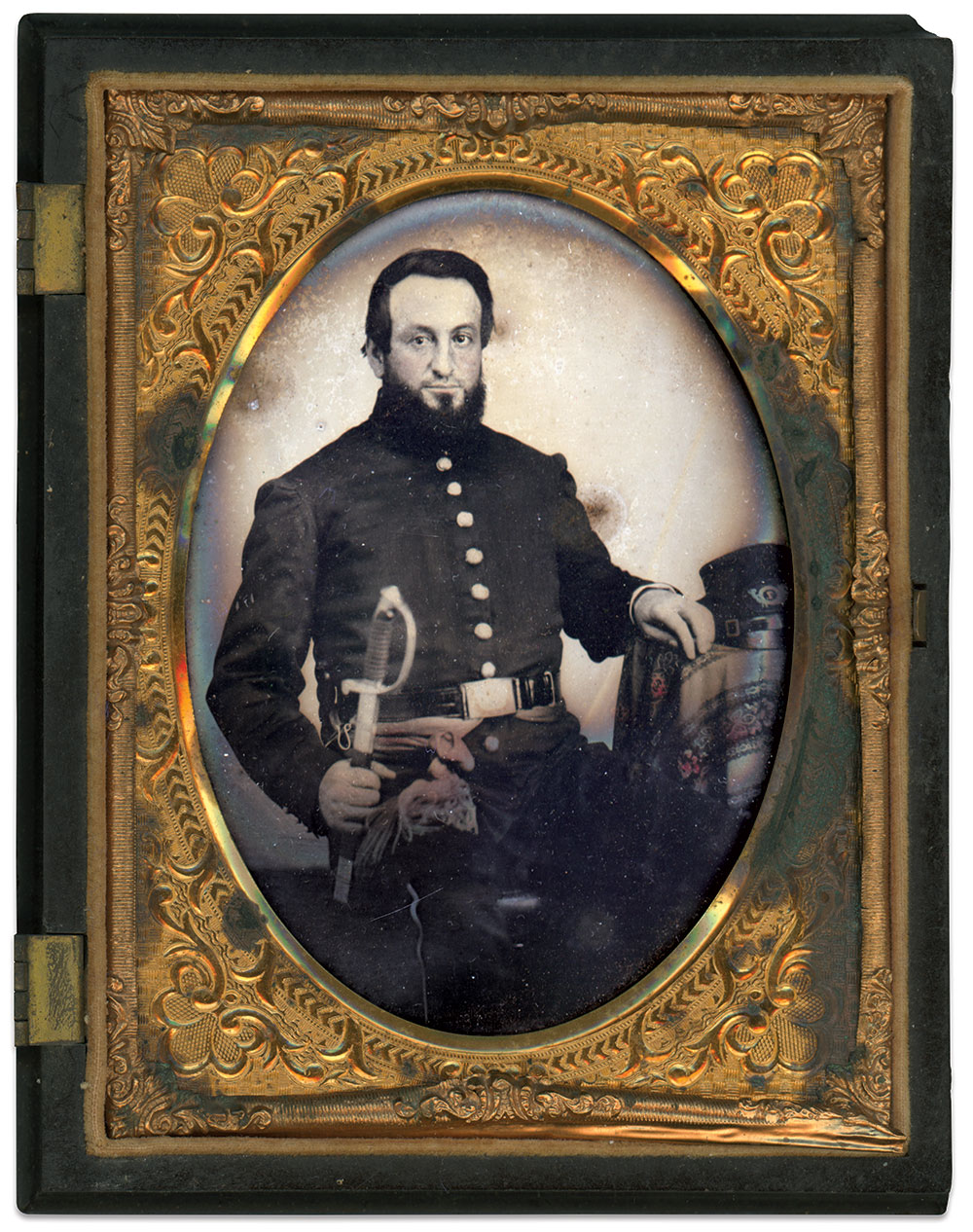

Six months after Crabb’s capture, in June 1862, as the Confederates retreated from Corinth, Miss., Isaac Avery fell into enemy hands. A peacetime attorney born in New York, he served as captain of Company A, 12th Georgia Cavalry, also known as the Georgia Mountain Dragoons. Captured by then Col. Phil Sheridan’s troopers between Booneville and Baldwyn, Miss., Avery was taken to Corinth. There he received a formal exchange and returned to the 12th. In January 1863, the regiment received a new designation as Georgia’s 4th Cavalry, and Avery advanced to its colonel and commander. At New Hope Church, near Dallas, Ga., in May 1864, Avery suffered a gunshot through the stomach, the bullet coming to rest near his spine. Thought to be a mortal wound, the Georgian beat the odds and survived. He used crutches most of the rest of his life. By 1868, Avery had become editor of the The Atlanta Constitution, and later authored The History of the State of Georgia from 1850-1881. He lived until 1897, dying at age 60.

An anonymous article published in The Constitution on Oct. 8, 1871, shed light on the connection between Avery and Crabb. The narrative has likely never been verified—until now.

The writer identified himself only as a captain in a Georgia cavalry regiment in service to Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard during the retreat from Corinth. He also stated that Sheridan’s men captured him and treated him well during his time in captivity. Moreover, that Maj. Gen. Halleck released him on his parole of honor, for two weeks only, to proceed to Confederate lines and track down a specific man for exchange—Capt. Crabb.

Recall that Crabb had been captured at Belmont six months earlier. If the writer could locate Crabb and effect a man-for-man trade, they would be considered free and duly exchanged. He detailed an arduous search, telegrams sent, and in-person visits to various prisons.

As the days passed, the writer contemplated his return to captivity. If he was unable to find the Iowan, he would have to turn himself back in as a prisoner to the nearest federal post in observance of his parole.

Our correspondent didn’t give up easily. With the clock ticking, he learned that prisoners were held in Macon. On the 14th and final day of his parole, he arrived at the Macon prison and, sure enough, found Crabb very sick, and, with regular exchanges at a standstill, hopeless of surviving his prison ordeal. The relieved Confederate captain produced official papers and completed the exchange.

It is a great story. But it seems far-fetched. Historians who study Iowa regiments were aware of the account, but, since there was no byline, no one knew the identity of the Confederate. To confirm the story, a researcher would have to work backwards to determine who wrote it. To identify the author, the Georgia cavalry regiments at Corinth would have to be identified and the record of each one carefully explored to determine which captains were captured.

Historians might dismiss such an account as a fabrication or exaggeration.

But it actually happened!

Avery’s military service record in the files of the National Archives detail his capture:

“Isaac Avery Captain of a Company of Georgia Cavalry Provisional Army of the Confederate States (PACS) taken prisoner in a cavalry skirmish between Booneville and Baldwin Mississippi June 1, 1862. Age—about 24 years. Complexion dark, face small, expression pleasing. Eyes dark. Hair dark and flowing. Height about 5 feet and 8 inches. Attached to Gen Hardees Army Corps. Headquarters Dept. of the Mississippi, Corinth, Mississippi, June 23, 1862”

This document confirms the terms of Avery’s parole:

“Capt. I.W. Avery will be released on parole to effect an exchange for Capt. Crabb, Seventh Iowa Vol. Infantry, U.S. Army, now in the Confederate lines. He will be allowed two weeks in which to affect the exchange, at the end of which time, if he fails, he will return and surrender himself a prisoner of war to the nearest U.S. Military Commander. By command of Maj. Gen. Halleck.”

Avery’s signed parole is also on file: “I, Capt. I.W. Avery, Georgia Dragoons, Confederate Army, a prisoner of war, do hereby pledge my parole of honor to proceed to the Head Quarters of the Confederate forces, to endeavor to effect an exchange with Capt. B. Crabb, Seventh Iowa Vol. Infantry, U.S. Army, a prisoner of war in the Confederate lines, captured at the battle of Belmont, and will not furnish aid or comfort to the enemies of the U.S. Government until duly exchanged. [Signed] I.W. Avery Capt. Ga Dragoons. Head Qtrs. Dept. Miss., Corinth, June 23, 1862.”

Avery could have easily slipped away without searching for Crabb. But he obeyed the terms of his parole. His persistence and determination likely saved Crabb’s life.

Sometimes the pieces of the story are out there, waiting to be found and reassembled.

Special thanks: The odds of finding a story such as this one, and verifying it by military service records, are extremely small. Having images of both men are even smaller! The carte de visite of Crabb is from the collection of Michael Huston of Wellman, Washington County, Iowa—Crabb’s place of residence. The tintype of Crabb is from the collection of Mike Rubino, who resides in nearby Indiana. The carte de visite of Avery is from the collection of David Wynn Vaughan—right in Atlanta where Avery edited The Atlanta Constitution. Many thanks to all for allowing use of these fabulous images from their collections.

Laura Elliott is an independent historian whose primary research interest is McLaws’/Kershaw’s division of Longstreet’s Corps. A family connection sparked her initial interest in Wofford’s Georgia brigade, and her research has gradually expanded to include all four brigades of that understudied division. She hopes to utilize her 10-plus years of research to write a regimental history of the 16th Georgia Infantry. Laura hosts a weekly virtual series for CivilWarTalk.com, which features historians, authors, and collectors. She lives near Gadsden, Ala.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.