One of the many joys of paging through back issues of Military Images is getting acquainted with collectors who were active during its early years. They shared their excitement and knowledge during the formative years of the hobby. They inspired a generation of seasoned and emerging collectors.

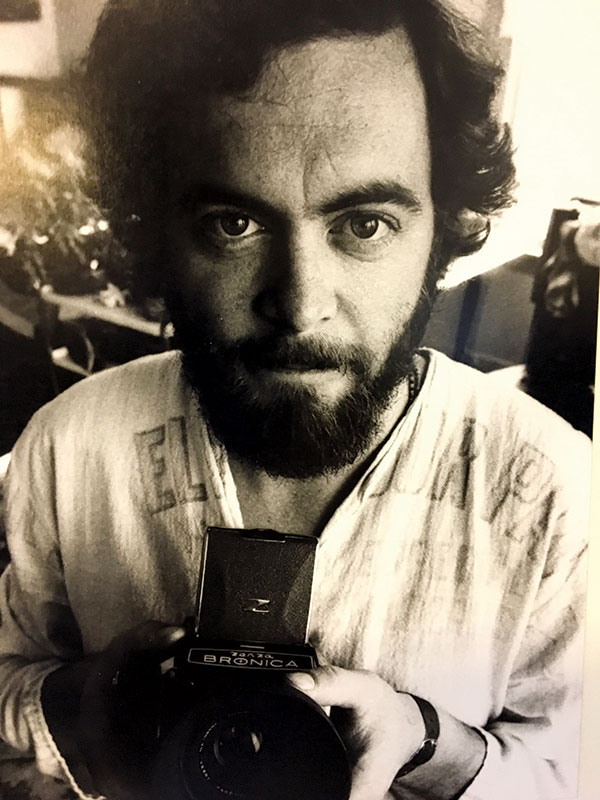

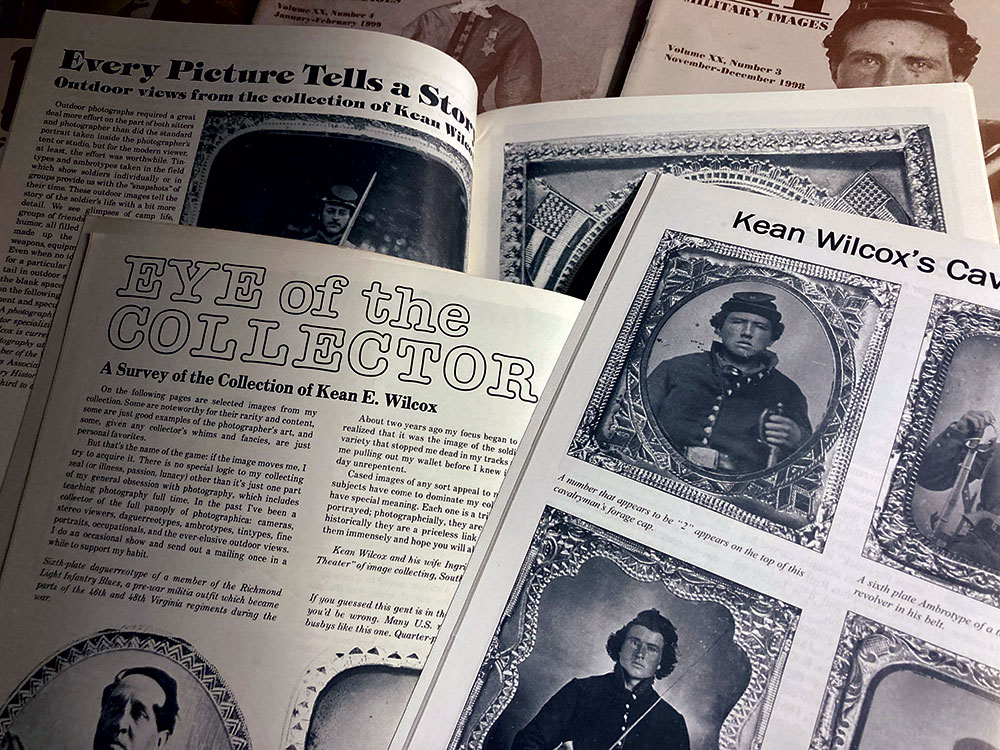

Standing tall among the ranks of these early contributors is Kean Wilcox, who exemplifies our mission to showcase, interpret and preserve. Cased images from his carefully built collection appear in 61 MI articles, including four major galleries, between 1982 and 2004. I reached out to Kean to learn more about how he became involved and his impressions of those times. In this interview, Kean reminiscences about his life as a collector during the pre-digital age.

Q: How did you become interested in the Civil War and 19th century photography?

I am 75 years old and spent my first 19 years growing up in Massachusetts. I had at least two relatives on my mom’s side of the family that served in the Union army.

I first became aware of the Civil War as a boy, as my dad was a real enthusiast and had a substantial library on the topic. As long as I treated his books with respect, I had full access to them. My dad also took me on an occasional field trip with his friend and fellow Civil War enthusiast. One such outing was to explore the location of a long abandoned Civil War era military prisoner of war camp.

Another childhood memory was that my grandma on my mother’s side had a vintage original Sharps rifle, which belonged to one of my relatives on her side of the family. We were allowed to play with this incredibly heavy rifle, and also the leather knapsack and canteen which belonged to this veteran who served in the Union army. I hung on to these memories as I graduated high school, served four years in the Marine Corps, and decided to get an education in California, where I was discharged.

As my formal education in photography began in 1971, I became aware that photography had a rich visual history, and that the Civil War was an important chapter in that history. When I completed my MA degree in applied arts in 1977, my interest and fascination with early photographic processes and techniques expanded. I was given the chance to develop and teach an undergraduate course in ‘The History and Criticism of Photography’ in 1978—and that sealed the deal.

I began to look for and purchase examples of early photographs for my own satisfaction, and to show my students. They seemed to really like seeing real examples of what we were discussing in class. My passion for Civil War cased image portraits stems from my having served in the U.S. Marine Corps and being a Vietnam Veteran. My dad (World War II) and older brother (Vietnam) were also Marine Corps veterans. Collecting Civil War portraits helped me to explore and share my personal feelings of pride and patriotism that weren’t necessarily shared by the general public during the Vietnam War era. Although I maintained my interest in all aspects of 19th century photography, my focus early on became cased images from the Civil War era.

Q: How did collecting in the pre-digital age era compare to today?

How does the horse and buggy era compare to the age of the automobile? In the 70’s and 80’s… no email, no Google, no online buying and selling, no online posting and sharing photographs, no online collecting groups in every area of interest, no social media. BUT!!! You can’t miss what didn’t exist. I visited antique dealers in person. I went to numerous large antique expos and shows. I received many hard copy catalogs from collector-dealers through the mail.

There was no “scanning” available in the pre-digital era. If you needed a copy of a given image, one had to photograph it with a camera. black and white or color slides. I sent and received black and white prints and color slides to and from fellow collector-dealers to make deals or just to share a new acquisition. I made lots of phone calls. I made a lot of friends, many of whom I met in person, some whom I never met face to face.

In the pre-digital age, we had the most amazing photographica trade fairs and shows. It was the golden age for collector-dealers in the field of vintage and historic photography and collectible cameras.

Unfortunately, the digital age eliminated some of the frequency for all those face-to-face gatherings. It was great fun collecting, which was challenging but satisfying. And, there was no eBay that requires all kinds of response, analysis and criticism.

Q: Did you find collecting on the West Coast presented unique challenges?

Yes! The Civil War took place 3,000 miles away. Harder to find Civil War cased images on the open market out here. On the flip side, there wasn’t as much competition in my chosen area of interest, so I had pretty good luck finding what was here on the West Coast. We also had some of the best photographica shows in the country, which were well attended by dealers from all parts of the country. I put together my entire Civil War cased image collection here on the West Coast. I never travelled to the East or Midwest to hunt for images. It was work—and great fun.

Q: Any favorite stories about collecting?

I really loved the excitement of the hunt, searching for cased images at antique stores, big antique shows, and antiquarian book fairs. One of my first Civil War finds was a fine quarter-plate tintype, beautifully hand colored, of a full length portrait of an artillery corporal standing next to an American flag draped over a posing column. This was 1977. Price was $25. That same year at another antique show I picked up a great sixth-plate tintype of a Union first sergeant identified as J.H. Boswell. He wore a slouch hat at an angle and had a big cigar in his mouth pointing upward in a rakish angle. Price was $30.

My favorite pleasant memory from the early decades of collecting in the 1970’s and 80’s relates to the early photographica shows that were popular during that time. These shows were basically specialized antique shows dealing with old photos and collectible cameras. One could find daguerreotypes, other cased images, albumen prints, stereoviews, CDV’s, cabinet cards, and every type of technique and process. If one wanted to gain insight into the history of photography these shows provided a great venue. The dealers and serious image collectors always gathered in the hotel hosting the show on the night before the show began, or the hotel nearest the show where we were staying. We room hopped all night doing show and tell, making deals, and buying and selling the best images, and greeting old friends. We swapped stories about our greatest finds and the ones that got away. I would describe it as “the most fun I ever had without being arrested.”

Q: How did your career inform your collecting?

My career teaching photography didn’t last as long as I had planned. I loved teaching the technical aspects, the aesthetics, and history of photography full time from 1979 to 1987 at a community college in southern California. It didn’t leave much time for my own photography, but it provided the motivation for a much deeper understanding of photographic techniques, materials, and the history and criticism of photography. It was also a motivating factor in collecting vintage photographs, which I included as part of my teaching and for my own satisfaction.

As an academic, I put together an impressive reference library on CW related topics—guns, uniforms, buttons, badges, belt buckles, swords and sabers. It was during this time as a teacher I discovered the benefit of becoming a collector-dealer of vintage photography, which helped me to have a means of paying for my ever-increasing acquisitions.

I had taken a sabbatical leave in 1985 to serve an internship at the California Museum of Photography located then on the campus of the University of California Riverside. I worked in the museum’s print collection, which at the time contained 10,000-plus images. I learned identification of the many processes, preservation and storage techniques, and cataloging procedures. My experience there helped me to make some career decisions and shift my focus from teaching photography to doing more of my own photography, and spending more time as a dealer-collector of vintage photography. I eventually resigned my faculty position and moved to the Pacific Northwest in 1988 to take a breather, and attend Washington State University (Go Cougs!) to earn an MFA degree in 1993. I was an adjunct faculty member there for a year, but mostly I was making and showing my own fine art photography and working on my collection of vintage photographs, which by now had shifted gears in the kinds of photographs I was after.

Q: Who were your mentors?

I had one. I met collector Noyes Huston from Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., in 1978 when I was just beginning to buy cased images. Noyes was an elderly man of about 70, long retired, and enjoyed painting and collecting vintage photography. A local newspaper had done an illustrated article showing me in front a nice group of my daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes, many of them in thermoplastic cases. I had recently run an ad in the classifieds announcing that I buy, sell, and trade vintage photographs. So, Noyes and I met up at my place and we eventually became collecting buddies. Noyes was an experienced and dedicated collector of stereoviews and cased images. His military cased images were superb.

He offered me some very sage advice about buying and selling, general aesthetics, and making the deal on a given photograph. He also taught me the value of a good trade as part of the deal. We acquired many great military images from each other over the years by trading. He shared his amazing pre-Civil War militia images and encouraged me to include that in my own collection, which I did. He was a mentor in every way for about 10 years until his passing, which was just about the time I backed away from teaching and moved to the Pacific Northwest.

Since then I have remembered Noyes Huston with every photo I have purchased or sold.

Q: A 1985 issue of MI includes a selection of representative images of your collection, “A Sharp Eye,” and the introduction notes your focus on “quality and detail.” Tell us more about your aesthetic.

Every collector of Civil War images makes choices, which help define what is important to them. Union or Confederate, weapons, identified or not, a specific state or unit, infantry, cavalry, artillery, outdoor images. Famous of known photographers. My choice in general was cased images: daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes. All of these processes are all direct positive photographs. No negative. What came out of the camera on a copper, glass or tin plate was processed and given to the sitter. Each photograph was therefore unique. No copies existed unless a second exposure was made or the photo was copied at a later date. I really liked that aspect of unique, one of a kind photographs.

I chose to collect Union and Confederate portraits of exceptional quality, wearing a variety of uniforms, armed whenever possible, rare and unusual weapons a bonus, of cavalry, infantry, artillery, and pre-war militia. I liked unusual or carefully posed portrait such as one of my MI back covers of a kneeling Union soldier in full marching gear, in the “prepare to repel cavalry” position with rifle and fixed bayonet pointing forward. I liked the portraits of young boys and bearded grizzled veterans on both sides. I really liked a photograph to stand on its own in terms of quality and content. Not all photos for sale made the grade.

I started to add outdoor subjects and views as my collection began to shape up. I had to look much harder and frequently made trades a part of the deal to acquire choice hard images. I had some good success: Mounted cavalry, camp scenes, outdoor portraits, casual group portraits, and a drummer boy leaning up against a wagon. Rarely were any of these cased images identified by photographers or subjects. These were photographs taken mostly by itinerant photographers making images for the soldiers, who mostly likely sent them home to relatives. These were the snapshots of the era.

I was a real fan of military and patriotic thermoplastic cases. If an image had no case, or a partial case, and no written documentation on it, I tended to upgrade to a pristine one. I believe I had examples of all the known designs and all sizes.

I loved having a clear perfect portrait of a soldier in a perfect case. Every single photograph in my collection was my own tribute to the patriotism, spirit, and humanity of all those that served. When the Civil War ended, they were all Americans again.

In general, I preferred those photographs that were deeply personal. I love the work of Brady, Gardner, Barnard, O’Sullivan and others, but their work was made for a different reason and audience.

Q: How did you become involved in Military Images?

A fellow dealer-collector (Jeremy Rowe, I think) at one of the Western Photographic Collectors Association shows held in Pasadena, Calif., knew of my interest in Civil War cased images and gave me a copy of Military Images. I couldn’t believe what I was looking at! Civil War cased images on the cover, back cover, in researched articles, classified section of dealers and research services. I became a subscriber and began submitting black and white copy photos of images in my collection, and had my first article published in MI Volume III (1982).

MI gave me the incentive to research identified images more thoroughly for publication. One of my earliest inspirations for collecting were the back covers illustrations found in Civil War Times Illustrated.

I was pleased to have many images from my own collection published in MI and ultimately became a contributing editor. I really felt honored and recognized as an “MI regular”!

Q: A digital search of our archives turns up 61 articles you contributed to, including four major galleries highlighting your collection. What motivated you to share so generously and often?

I was an experienced photographer as well as a collector. This gave me the advantage of making my own copy photographs of images in my collection. I could copy images in black and white, process the film and make prints in the darkroom very soon after acquiring enough new images to require it. This allowed me to stay current on my submissions to MI.

I had photographs from my collection published in the journal The Photographic Collector (1983 and 1985) and North & South: The Official Magazine of the Civil War Society (2002).

I sent color slides to book publishers and had great success getting illustrations used in the Time-Life Books series on the Civil War, including the Master Index volume (1987) and Echoes of Glory: Arms and Equipment of the Union (1992). Thomasson Grant Publishers used 11 photographs and a back cover in their 1988 book Distant Thunder: A Photographic Essay on the American Civil War, with photographs by Sam Abel and text by Brian Pohanka. Time-Life and Thomasson Grant used my photographs in calendars in 1988 and 1989.

I also had more photographs published in four other books: Private Soldiers and Public Heroes: An American Album or the Common Man’s Civil War (1988) by Milton Bagby, The American Civil War Sourcebook (1992) by Philip Katcher, For Home and Country: A Civil War Scrapbook (1995) by Norm Bolotin and Angel Herb, and Great Battles of the Civil War: An illustrated History of Courage Under Fire (2002) by Neil Kagan, et al., editors.

I was pretty serious in my personal pursuit to spread the word and raise awareness of the patriotism and service exemplified by these incredible Civil War era cased images.

To be accurate, my collection took on a life of its own. For many years after I had stopped collecting military images, requests came in for photos, or permission to use or reuse a photo, and many times notification that a publication had used a photo and would I like a copy of the book. Much of my time and energy after I had moved to the Pacific Northwest in 1988 was spent on making and exhibiting my own fine art photography. There was a pretty good overlap and it was very gratifying that there was continued interest my Civil War cased image collection.

Q: Why did you stop?

I never stopped collecting photographs, only military images. I had done everything I set out to do. I built a fine collection of Civil War related cased images, I mounted displays, gave lectures, published the photos in magazines, journals, books, and calendars. I waged a one-man campaign to contribute to appreciating all veterans, present and historic. As my own interests in photography shifted from teaching to my own fine art photography, my collecting interest shifted to vintage fine art photographs from 1880-1920. This was the golden age of pictorial photography and was a time of great creativity, new processes and photographic techniques, huge growth in aesthetics, subject matter, and the recognition of photography as fine art.

Q: You mentioned to me prior to this interview that you’ve sold off your Civil War images. When did that happen and why?

I started selling off my military image collection about the time I was moving to the Pacific Northwest. I sold it one at a time, sometimes to fellow collectors who had made a request: “If you ever sell this one, let me know.” Sometimes in a trade for others photographs I was seeking out, and usually in face-to-face deals at shows and such. I generally did not offer them on public auction venues such as eBay. If I could afford it, I would have considered donating the whole collection to an institution. I wasn’t and am not wealthy, so put my images back into circulation and made a lot of collectors pretty happy.

Q: What’s your focus now?

I am working on Woodburytypes (1870-1895). I have worked on, displayed, and in some cases sold collections on these topics:

- Pictorial photography (1880-1920)

- 19th century books illustrated with original photographs

- Albumen prints with a variety of subjects, specific photographers

- Artistic nudes (1870-1930)

- Guitar players in all formats (1860-1930)

Q: Words of wisdom for today’s collectors?

If you are going to collect photographs, collect the best examples. Don’t start at the bottom level and work your way up. Be aggressive in the search, patient in your selection, and honorable in making the deal. I think all successful collectors know that. To all current Civil War photography collectors out there, I salute you. Good luck in your hunt.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.