By Charles T. Joyce, featuring images from the author’s collection

The courage and sacrifice by two undersized brigades of U.S. Regular infantry during the second day at Gettysburg evoke an observation by historian Bruce Catton in Mr. Lincoln’s Army: It “may be that life is not man’s most precious possession, after all. Certainly men can be induced to give it away very freely at times, and the terms hardly seem to make sense unless there is something about the whole business that we don’t understand.”

The story of the hard-fighting brigades and representative soldiers on July 2, 1863, illustrates Catton’s words.

Recalled from the West to fight

In 1860, the rolls of the U.S. Regular infantry included about 8,000 officers and men, posted mainly at far-flung western forts and along the Canadian border. The outbreak of Civil War reduced its effectiveness almost immediately, as fully a third of the officer corps resigned to join the new Confederacy. A War Department report to Congress lamented that “but for these startling defections, the rebellion never could have assumed formidable proportions.”

On the upside, few noncommissioned officers and enlisted men joined them, as many were foreign-born and had no attachment to the slave-holding South. These well-trained soldiers carried forth the traditions and history of the army dating to the Revolution.

President Abraham Lincoln acted quickly to staunch the bleeding. He proposed augmenting the U.S. Infantry ranks by approximately 20,000 troops, from ten to 19 regiments.

Federal recruiters immediately ran into trouble. They could not compete with their counterparts in state and local governments. The state volunteers received higher bounties. They generally drilled less compared to the “Regs,” as the men of the U.S. Infantry referred to themselves, who marched and maneuvered an additional hour each day. State volunteers also received more attention on the home front. The Regulars were oftentimes neglected; one sagely complained that his outfit lacked “Congressmen, local newspapers and ladies’ aid societies ever on watch over the interests and needs of home organizations; caring for their wounded and praising publicly their deeds,” all the while furnishing “supplies and delicacies that the army could not provide.” In the end, Lincoln’s plan never came close to realization.

Two years of harsh but unheralded combat

In the spring of 1862, the Army of the Potomac mustered five corps of 15 divisions. Only part of one division included Regulars. Five U.S. regiments and a group of battalions composed the first two brigades of the Second Division of the Fifth Corps. The Division’s Third Brigade included all volunteer organizations, including Duryée’s Zouaves—the 5th New York Infantry. Regular artillery batteries supported the Division. A highly capable West Pointer, Brig. Gen. George Sykes, commanded the Division. He reported to Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, who led the Fifth Corps.

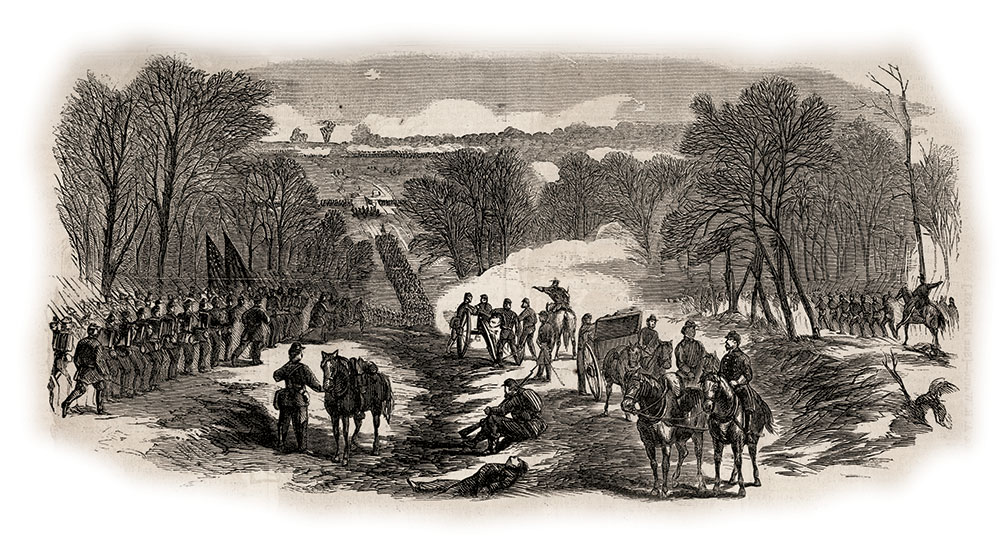

The overall commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, used Sykes’ Division as a tactical reserve. He ordered it into combat to cover retreats or as shock troops to spearhead or exploit a breakthrough. At Gaines’ Mill they advanced to a hilltop to stem the Confederate attack, a mission completed at enormous cost, leaving McClellan to write: “My Regulars were superb, and I count upon what are left to turn another battle, in company with their gallant comrades of the volunteers.” At Second Bull Run, they again were called upon to hold their line to avert a disaster, losing more than 900 men in the process. And, at Fredericksburg, sent in to relieve beleaguered troops pinned down in front of Marye’s Heights, they spent a miserable night and next day lying in the mud under galling rebel fire, surrounded by dead and dying.

The Regs showed their offensive capabilities at Antietam and Chancellorsville, but timidity at headquarters or lack of battlefield support by volunteers thwarted their efforts.

At Antietam, they advanced at the day’s end to make one final push to sunder Lee’s lines before McClellan recalled them. Anger rippled through the ranks, and the men of the Regular Division never had the same fervent loyalty to “Little Mac” thereafter. A captain in the 3rd U.S. wrote, “The regiment is a mere skeleton of its former self and looks more like a company than a Reg’t. We are kicked and cuffed while the volunteers are petted and spoiled.”

At Chancellorsville, they took key ground in a disciplined attack, but relinquished it when supports failed to reach their advanced line. Later in the day, Regular Division bands formed in parade ground style and played national airs to help contain the flight of the army in the face of Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s surprise flank attack. For the first time—and the last—the Regs garnered popular recognition.

The final march of Syke’s Regulars begins

By the early summer of 1863, the Regs faced a fresh menace to its fighting strength from an old antagonist: Draft-induced bounty payments for state volunteers reached stratospheric heights, tempting recruits with as much as $3,000 to enlist. Desertion from the Regs ranks to “bounty jump” to newly forming state battalions, combined with ever-anemic federal recruiting, combat losses and disease, reduced the two brigades of U.S. troops to barely 2,500 officers and men.

On June 13, William Sanderson of the 2nd U.S. remembered, “just after taps had sounded and all the boys were snugly ‘spooned’ up together beneath their shelters,” the “general call” was sounded, and at the same moment, the clouds opened with a torrential downpour. “There was much scrambling and swearing as the boys pulled out into the rain, and the noise of striking tents, drawing rations and ammunition, combined with the neighing of horses, braying of mules, the rattle of sabers, [and] the hoarse command of officers,” made the event “extremely exasperating.” Sanderson added, “We took up the line of march down a slippery hill, illuminated only now and then with a flash of lightning. … I will never forget the scene as we started on that long march for the then unknown Gettysburg.”

A tale of two officers with something to prove

As the Regulars trudged north through one of the most brutally hot summers in memory, two men anticipated the coming fight with eagerness and apprehension perhaps greater than most. Both were civilian appointees tapped to fill the void left by West Pointers who had resigned to join the Confederate army.

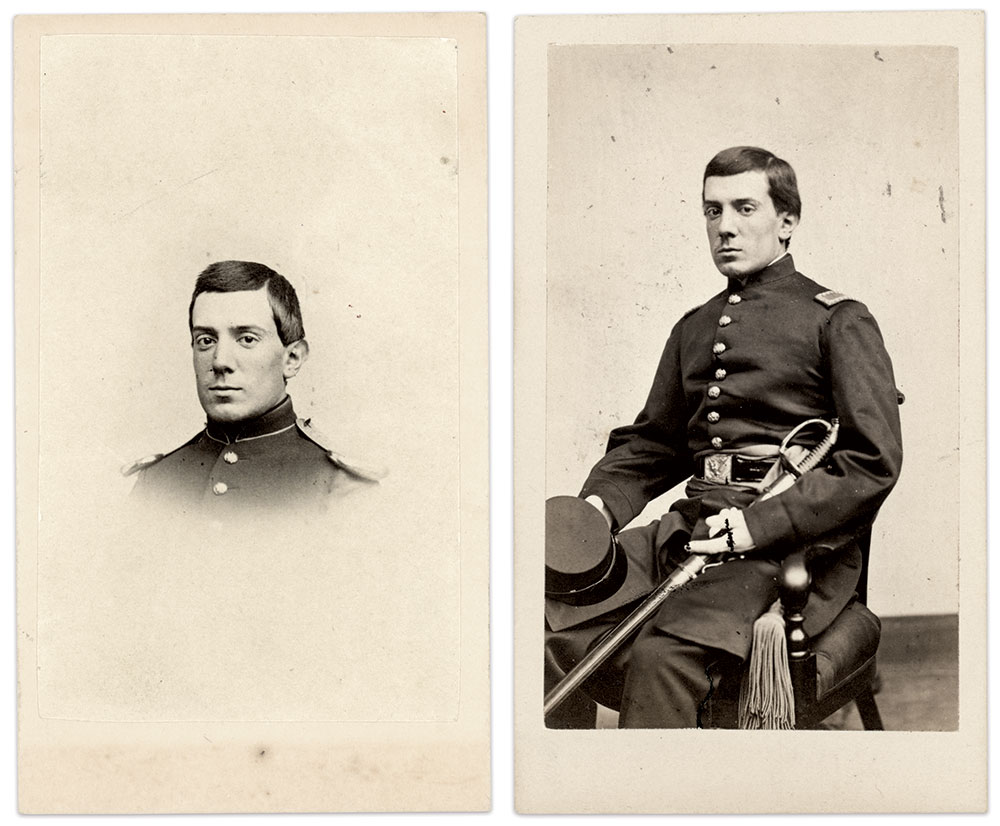

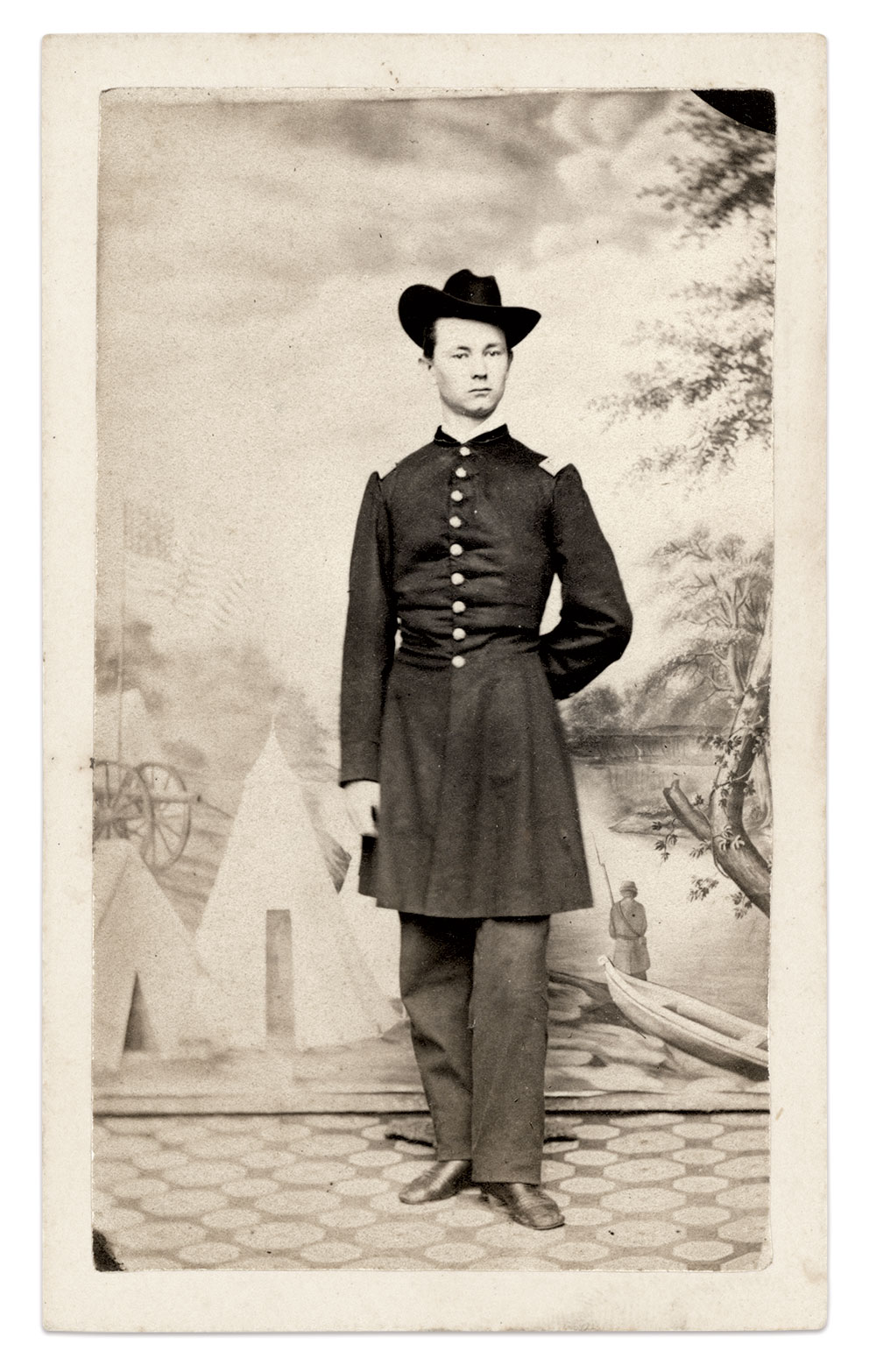

One was 2nd Lt. Edward Stanley Abbot of the 17th U.S. Infantry. Born in Massachusetts, the 22-year-old was the second to youngest son of Joseph Hale Abbot, a renowned professor whose grandfather was the brother of the Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale.

Despite his great uncle’s martial fame, Stanley had no interest in becoming a soldier. But after the war came, he determined to join the army. His parents objected, and he chafed under their restrictions. He wrote to his sister Emily that, “they don’t trust me much at home. They think I want to be a ‘gay soldier boy.’ It is really hard and bitter that Mother thinks I am so boyish.”

Stanley sought help in securing a Regular Army commission from his older brother, Henry, an 1854 West Point graduate and topographical engineer in the Army of the Potomac. Before Henry could ply his political connections, an impatient Stanley enlisted as a private in the 17th. He explained to sister Emily: “I wished to prove that I was not going because I was dazzled by brass buttons, as you all thought.” He added, “I am not one of those lack-a-daisical would-be-heroes who consider that a soldier’s duties can be fulfilled by simple, romantic bravery. I know perfectly well that courage is only a small part of what is needful. Strength, health, knowledge of the business are indispensable — I shall acquire them.”

Stanley understood the challenges to his country and opportunities for those who would defend it. “I fear the chances are against us,” he wrote his sister. “At any rate, if we do succeed, it will be by the exercise of every power we are master of. Every man who can strike a blow will be bitterly missed if he dare not come forward in his country’s time of agony—I cannot be such a man, Em. I think it is a glorious thing when one has a chance to be a hero.”

At the Battle of Chancellorsville, Stanley “saw the elephant.” He described his mindset to his exceedingly pious brother Edwin, noting he had fallen short of being a “Christian soldier” who should “be brave without allowing evil thoughts of hatred and anger to master me.” He confessed that it drove “the devil into my heart to hear those screaming demons rush at us through the smoke.” He insisted that, “I know it is wrong, and I will be stronger next time.”

The other soldier, Francis “Frank” Chester Goodrich, 25, also hailed from Massachusetts. He had entered West Point in 1854, but grew tired of military instruction and transferred to Harvard, graduating in the class of 1859. When the war broke out, he joined the 3rd Massachusetts Militia, claiming to be “the first Boston Boy who shouldered a musket in defence of the Union.”

After his three-month enlistment expired, Frank secured a first lieutenant’s commission in the 2nd U.S. Infantry. He did so with the political influence of his father, Charles, a Boston lawyer and prominent Democrat who aided the war effort with a well-received speech immediately after the attack on Fort Sumter, “renouncing all party considerations to sustain and support the government.” This act, according to his Congressman, Samuel Hopper, “at once settled the position of the Democratic party in New England in regard to the war.”

Frank had his first taste of real combat at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill during the Peninsula Campaign. He left the field in the face of the enemy, failing to return to his men until nightfall. His incensed commanding officer court-martialed him. Frank unwisely conducted his own defense. The Court found him guilty and ordered his immediate dismissal from the army. His sentence made newspapers across the nation, including the Boston Daily Evening Transcript, which reported that he had been removed because of “misbehavior before the enemy.”

Frank’s father explained in a letter to President Abraham Lincoln that Frank had left the field because he had been ill with malaria, adding that several officers had spoken “in high terms of his manliness.” He requested that his son be restored to his regiment. “I cannot doubt that he has tried to do his duty,” he pleaded, and “please pardon the liberty of a father and … permit my son the opportunity of another effort.” What the President did with this plea is unknown.

Meanwhile, his father followed up with a flurry of letters to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and enlisted U.S. Senators Solomon Foot of Vermont and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, and Congressman Hopper to aid in the campaign to save this son’s reputation.

Senator Wilson implored Stanton to return Goodrich to command and give him “a chance to redeem the past, which I am confident he will do with his blood if need be.”

This political pressure prompted the War Department to modify Frank’s sentence to a six-month suspension and loss of pay.

Frank returned to the regiment and with the same rank at the end of December 1862. The following spring at Chancellorsville, he managed to stay in the good graces of his commanders.

New leaders on the eve of battle

As the Regulars approached Gettysburg, the Army of the Potomac’s commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, resigned. The War Department sent a peremptory order to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade to assume overall command. His elevation prompted a series of changes in the Fifth Corps chain of command.

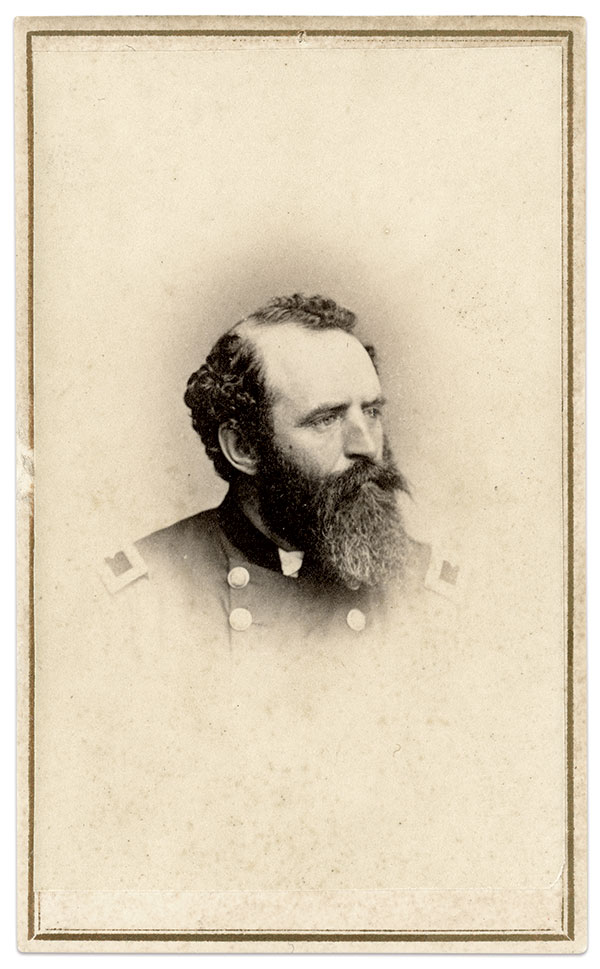

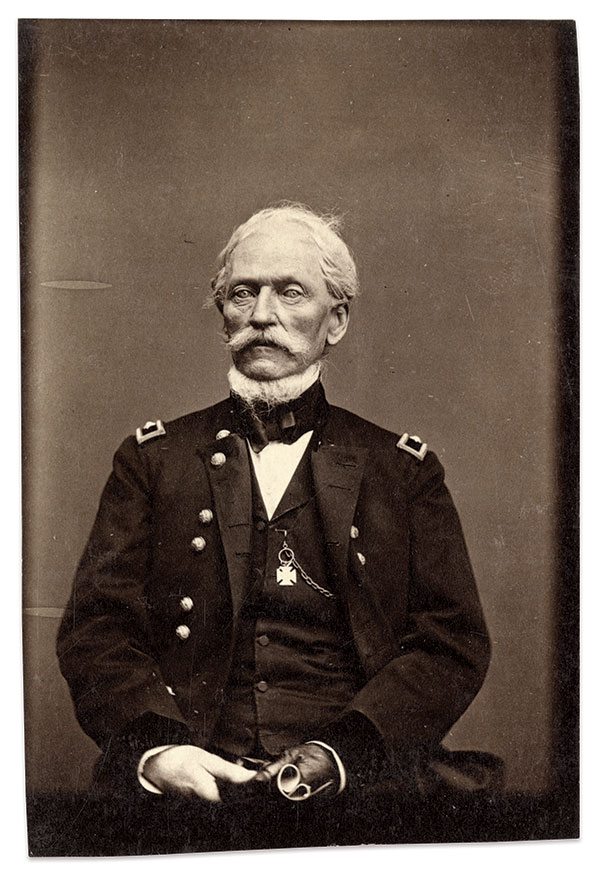

Sykes replaced Meade in command of the Fifth Corps. Romeyn B. Ayres filled Sykes’ spot in command of the Regulars’ Division. A 38-year-old career soldier, the crusty brigadier held his command to great expectations. A sketch of Ayres’ service reveals just how high he set the bar: When one of his colonels displayed timidity before the enemy, Ayres made sure he was in the thick of the action the next day. Informed that the colonel had been killed in the fight, Ayres exclaimed, “Thank God! His children can now be proud of him.”

Hannibal Day was given command of Ayres now former brigade, composed of companies of the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 12th and 14th U.S. Day, a colonel who had spent 40 of his 59 years in the Regular Army, had not held a combat command since the Mexican War.

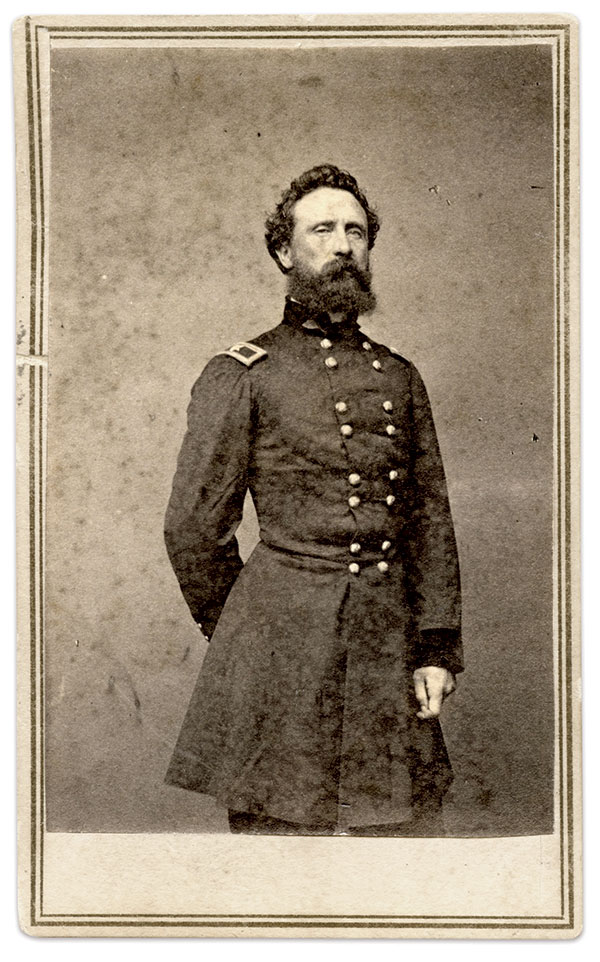

The other brigade of Regulars, including the 2nd, 7th, 10th 11th and 17th, remained under the leadership of 55-year-old Col. Sidney Burbank, who had led that outfit only since Chancellorsville.

Day of destruction

Reveille for the Ayres’ Division sounded at 3 a.m. on the morning of July 2, and after a two-hour march the Regulars reached the battlefield. They occupied a meadow near the Union right flank and rested while awaiting orders. Soldiers slept or boiled coffee; others volunteered to fill canteens from the waters of nearby Rock Creek.

The day wore away until late in the afternoon, when the Division received orders to move to the left as quickly as possible. The Brigades marched double quick time through fields and over fences in the stifling heat, until wiser heads prevailed and slowed the pace to a quick time to prevent exhaustion before going into action. The troops arrived on the north slope of Little Round Top. What they glimpsed as they squinted west into the sun and down at the sweeping panorama of the valley below alarmed them.

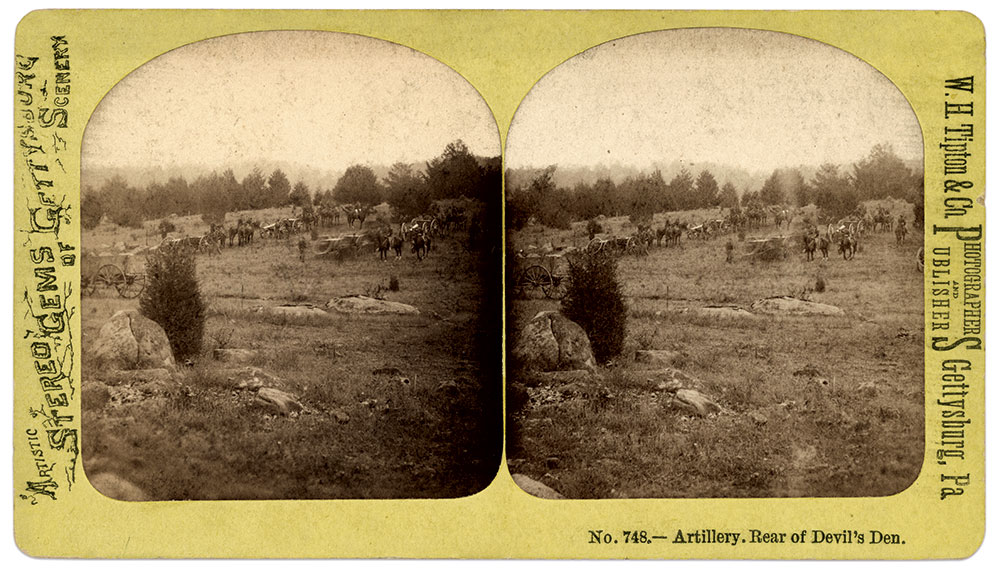

To the left the Regulars observed Confederates — Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s Division of Georgians, Texans and Alabamians — pushing back Union forces arrayed in Devil’s Den and along the crest of Houck’s Ridge. These federals belonged to the extreme left flank of Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles’ Third Corps.

To the right the Regulars watched Union forces — the leading brigades of one of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s Second Corps divisions — commanded by Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell — moving into farmer Rose’s Wheatfield to confront Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s brigade of South Carolinians.

A yawning gap existed between the two scenes. Ayres’ Regulars received orders to fill it. Burbank’s Brigade formed in line and advanced down the slope of Little Round Top in a parade ground order that took them through a marsh 50 yards wide along a stream at the valley bottom. Day’s Brigade followed in column close behind.

The men marched in silence as the grim reality set in. An overzealous first lieutenant in the 17th provided a moment of comic relief when he began running in the rear of his company yelling, “Give ‘em Hell, men, give ‘em Hell!” His ardor got the best of him, however, and, tripping over his sword scabbard, he fell face first into the muck, to the laughter of many.

Just then, enemy rifle hit them from Confederates swarming over the rocks of Devil’s Den. The order to charge was given and the Regulars ran up the slope of Houck’s Ridge, cheering as they sprinted into action. Ayres later described the cheer as “in the nature of shrieks.” A private in the 15th Georgia Infantry was perhaps more generous than Ayres in his recollection, which he described as a “manly cheer” of “hip, hip, huzzah” that reverberated across the valley.

In the midst of the cheering men and the zip of bullets, a Minié ball thudded into the right breast of 2nd Lt. Stanley Abbot of the 17th. The slug passed through his lung and lodged in his spine. Comrades carried him from the field unconscious.

Abbot’s comrades and the rest of Burbank’s Brigade continued on toward a stonewall on the crest fronting a woodlot between Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield. Day’s Brigade formed behind them on the reverse slope of the hill.

Ayers evaluated Burbank’s position. On his left flank, the 17th occupied a deep gully dominated by the Devil’s Den ridge. If pressed, Ayres reasoned, it could not be held. On his right flank, the 2nd occupied the more elevated ground bordering the northeastern corner of the Wheatfield.

Ayers judged the high ground a more advantageous position and ordered Burbank’s Brigade to execute a left wheel into the Wheatfield and drive away Confederates from that sector.

Burbank’s men pivoted on the 17th. The 2nd, 7th, and the rightmost companies of the 10th moved into the open and began to turn the wheel. They had almost completed the maneuver when a brigade of Georgians led by Brig. Gen. Paul J. Semmes burst out of Rose Woods and fired into their ranks. The Regulars responded in kind and stopped the Georgians’ advance.

Then, disaster struck. Another brigade of Georgians, commanded by Brig. Gen. William T. Wofford, slammed square into the exposed right flank of the 2nd. Wofford’s troops swarmed the 2nd, firing with deadly accuracy on the regiment’s right, front and rear.

It was here that 1st Lt. Frank Goodrich met his end. Killed in the heat of battle, he proved Senator Wilson’s words sadly prophetic: Goodrich’s blood removed the stain that had tarnished his reputation.

By this time, the Georgians had made the position of the 2nd untenable. On the other side of the Regular’s line, the 17th faced intense fire from rebels who had broken the last ditch Union defense at Devil’s Den. Burbank ordered his Brigade to fall back, but in the chaos and confusion only the 2nd and 7th initially heard it. The 10th, 11th, and the harried remnants of the 17th held on and took fearful losses, as elements of four different Confederate brigades poured a withering fire into the regiments.

The stories of two casualties in the Regulars’ ranks are representative of the severity of the blow dealt by the Confederates.

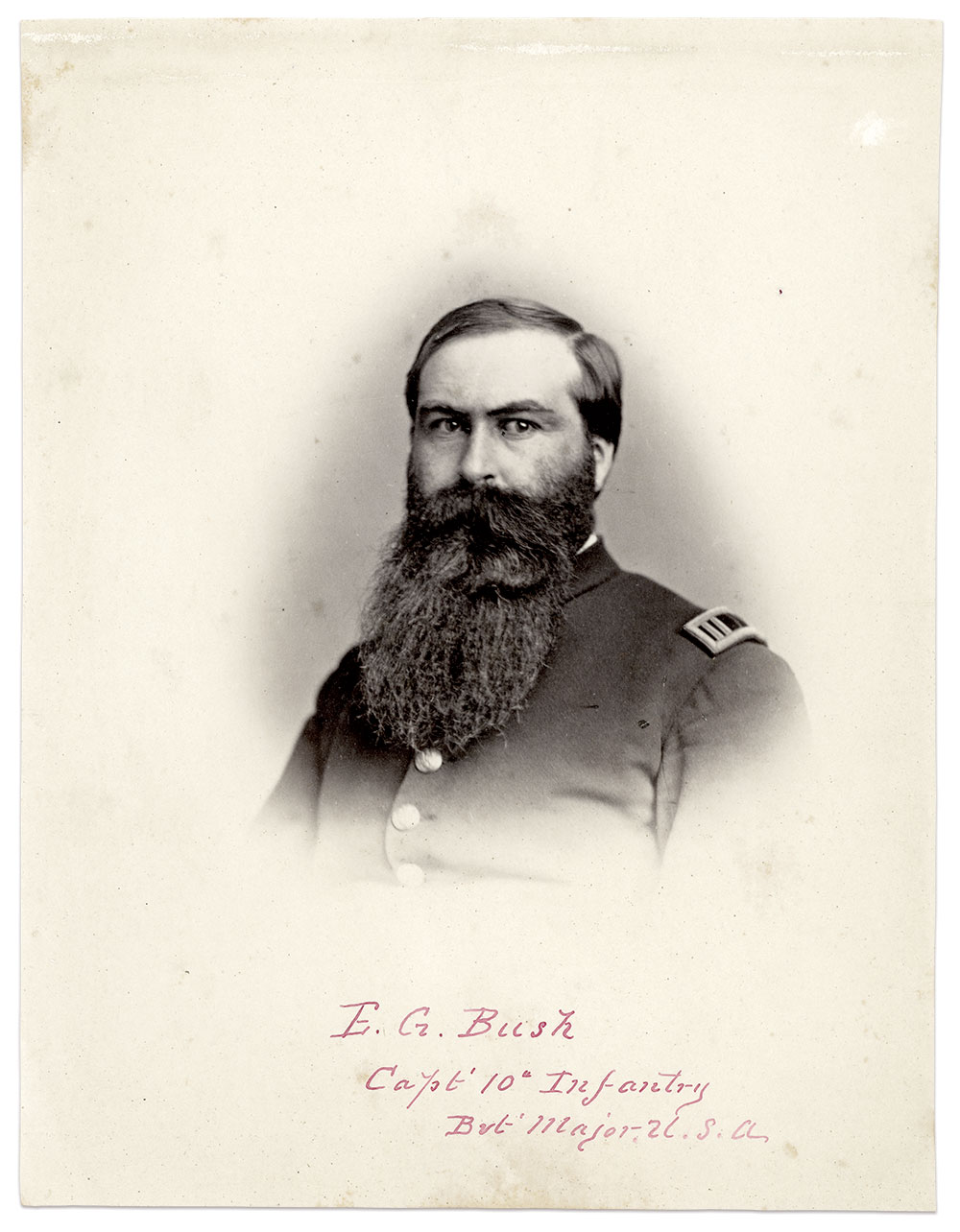

In the embattled 10th stood 20-year-old 2nd Lt. William James Fisher of Delaware. He grew up on a farm owned by his father, Isaac, in Sussex County, where about three-fourths of Delaware’s 2,400 enslaved people resided according to the 1860 U.S. Slave Schedules. Fisher went off to war in 1861 at age 17, accompanied by a black servant named George. Two years later at Gettysburg, as the 10th traded volleys with Semmes Georgians, a rebel Minié Ball struck Fisher. According to a fellow second lieutenant, Robert Welles, Fisher suddenly clasped his hands upon his breast and fell. Then, Burbank’s delayed retreat order arrived. Welles and three other men, including a sergeant and Capt. Edward Greer Bush, carried Fisher out of harm’s way. They made it as far as Plum Run before the sergeant fell wounded and a bullet struck Capt. Bush in the hand. Welles continued on with Fisher until he too suffered a wound. By this time, Fisher succumbed to his chest wound. Captain Bush came upon Fisher’s lifeless remains and rescued his pocket watch, but left the body behind.

Rebel lead struck men and officers in the nearby 11th with alarming accuracy. One bullet tore into the thigh of 2nd Lt. Abram Alexander Harbach, a native of Pittsburgh who lived in Iowa at the start of the war. He had served a three-month stint in the ranks of the 1st Iowa Infantry and experienced his first major combat at Wilson’s Creek, Mo., before joining the Regulars. Harbach made his way to safety despite the nature of his injury.

The remnants of the 17th remained on the field in a hellish fight for its survival. English-born drummer boy Matthew F. Kippax recalled that now “muskets were clubbed, and in the frightful melee bayonets, swords, pistols, knives, and even stones were used. All forms of humanity were forgot, and the brute instinct in man predominated.”

And what of Ayres? Historian Tim Reese, in Sykes Regular Infantry Division, 1861-65, noted “If ever there was an instant where Romeyn Ayres might have considered panic, that moment was upon him.” Federals watching from the heights of Little Round Top expected the two brigades to disintegrate in flight for the rear.

Ayres treated them to a different scene. He ordered his men to turn and march methodically away from the combat. A captain in the battered 17th insisted that not “a single man left the ranks, and they allowed themselves to be decimated without flinching.” A corporal in the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry on Little Round Top reported the Regs “reluctantly fell back as if on drill.” He added, “I am glad, as a volunteer, to bear tribute to the United States Regulars.”

The Regulars paid a high cost in blood for this parade ground maneuver. The rebels formed what amounted to a semi-circular ring of fire extending from the crown of Devil’s Den to the elevated corner of the Wheatfield. They picked off more of Burbanks’s men.

Day’s Brigade, in reserve behind Burbank, had not suffered severely up to this point. This soon changed when several of his regiments received orders to fire volleys at the rebels to buy time for Burbank’s men to escape. In this action, Pvt. Hugh J. Sharp, an Irish-born harness maker in the 14th, received a wound in the hip, while four others in his company suffered mortal abdomen wounds. “The few hundred yards to the foot of Little Round Top, already strewn with our disabled comrades, became a very charnel house,” wrote another soldier in Day’s command.

As the Regulars approached the safety of Little Round Top, Union artillerymen along the crest depressed muzzles of the guns towards and prepared to spray canister at the rebels in close pursuit. Battery commanders frantically waved their hats and urged the Regulars to hurry up so that the artillerists had a clear field of fire. But exhaustion and the swampy ooze in the valley slowed progress. The batteries belched canister, and some Regular infantrymen were likely killed or wounded by this regrettably necessary artillery action.

Just as the bloodied Brigades reached the main Union line, a fresh force of federal infantry appeared and swept down the slope of Little Round Top. By this time, according to a veteran of the 2nd, “the rebel line was badly broken; in fact, so far as I could see, it was a crowd, without any tangible line, and it was evident that a well-directed attack by an organized line of battle could easily drive them from the field. History tells us that this was done by the troops just coming onto the scene of action, but the Regulars had broken the force of the attack of the enemy, thus preparing the way to an easy victory.”

The awful aftermath

The price of the Regulars’ obstinate stand and stubbornly slow retreat told in the regimental casualty lists. Caught in the open in the Wheatfield, the 2nd lost 13 of its 26 officers and nearly 35 percent of its men. The losses of the other regiments in Burbank’s Brigade were even worse. The 7th lost 45.7 percent of its effective strength. The 10th, which had entered the battle with only 93 officers and men, lost more than half its number. The 11th had a casualty rate of 42.7 percent. And the 17th, which had fought hand-to-hand in the dark valley between the Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield, lost 151 officers and men — a whopping 58 percent of those engaged. Casualties in Day’s Brigade were not as high but still frightful. Nearly a quarter of its men and officers suffered death, wounds or capture.

The Regs turned to the care of its wounded and burial of its dead.

Private Hugh J. Sharp of the 14th received treatment for his hip wound at a field hospital and then moved to the U.S. General Hospital at York, Pa., to recover. A carte de visite he had taken there pictures him with a cane in hand and a haunted look on his face, as if the horrors of Gettysburg remained with him.

The remains of 2nd Lt. William Fisher of the 10th were buried on the battlefield. A private in his company inscribed Fisher’s particulars on a piece of wood from a sugar box that served as a headboard. Isaac Fisher traveled from Delaware and brought his son home. He also received William’s watch and other personal items. His sword and scabbard were not among them, having been left behind in the rush to get Fisher out of harm’s way during the fighting. The private who inscribed the headboard also wrote a consolation letter, assuring the father that his son “was greatly missed in the Company, in fact in the whole Regiment.” He added, “There was not one man in the Regiment … but what thought a great deal of him … he wasn’t cross like some of them, he was kind and genteel to all of us.”

Members of the 2nd fashioned a wood headboard carefully inscribed in black for 1st Lt. Frank Goodrich, buried near where he fell. His father, Charles, who less than a year earlier had employed political influence to restore his son’s commission, came to Gettysburg and bore his son’s body back to Massachusetts. Later in the century, when West Point erected its war memorial to honor their cadets who fell in defense of the Union, Goodrich’s name was included even though his time at that institution had been short and incomplete.

An unconscious Lt. Stanley Abbot of the 17th was removed to the Fifth Corps field hospital, where he rallied from his injury. A brother officer, also wounded, lay by his side and reported that Stanley awoke, sat up, “and spoke in a full, natural tone.” Abbot had strength enough to telegraph his pious brother Edwin in Boston: “Wounded in the breast. Doctor says not mortal. I am at corps hospital, near Gettysburg. Expect to be in Baltimore in a few days.”

Edwin received the message on July 7 and took the next train to care for him. Unfortunately, that very day Abbot’s condition worsened and he died the following morning. Edwin arrived only to learn that Abbot was dead and buried. Directed to his grave, the brother observed, “It was so suitable a place for a soldier to sleep.” He explained “that I was reluctant to remove the body for any purpose. But the spot was part of a private farm; and as removal must come, I thought it best to take the body home, and lay it with the dust of his kindred.” Edwin had his brother’s remains disinterred with the help of a few wounded Regulars. One of them told him that Abbot “was a strict officer, but the men all liked him. He was always kind to them.” Edwin concluded, “That … was his funeral sermon.”

Extinguished and remembered

The remnant of Regulars marched from Gettysburg—a division now in name only. It had ceased to exist as a cohesive unit by early September 1863. After the war, when monuments erected by the states to honor volunteer regiments began to pepper the battlefield, none bore markings where Burbanks’ and Day’s boys had fought and died. Dudley Chase, who had commanded a company of the 17th there, visited the battlefield in 1886 and bemoaned the fact that there was what he described as a “vacancy” where he and his comrades had held off the rebel hordes.

The void remained until the end of the first decade of the 20th century when one of the Regulars stepped in. Abram Harbach, who had survived his Gettysburg wound, stayed in the service, and rose to the rank of brigadier general, helmed a committee to create monuments to mark the Regs’ position. The memorials to “Uncle Sam’s hired hands,” as the old veterans of the Regulars by then called themselves, were modest and uniform — polished slabs of Jonesboro Red Granite with bronze plaques telling the official story of what had happened on Houck’s Ridge on that long ago July late afternoon. Few visitors to the battlefield today stop to visit this spot.

Along with these seldom-viewed stones, Ayres’ boys are mentioned on a simple but imposing granite obelisk that crowns Cemetery Ridge a few miles to the north. It salutes all the Regulars, including those in artillery and cavalry units that participated in the battle. Here, in 1909, President William Howard Taft intoned, “with no one to blow its trumpets,” the U.S. Infantrymen who had traded their lives for time and helped to save the Union cause had forged “a record of duty done that should satisfy the most exacting lover of his country.” The press described Taft’s tribute as “Tardy Recognition of the Nation’s Debt to its Brave Defenders.”

Another tribute to the Regulars’ sacrifice came from the crusty commander whose orders they obeyed with painful precision. As he neared the end of his life, Romeyn Ayres found his thoughts returning again and again to Gettysburg, and what that fight had wrought to the men he had led. “I wish the old Division was in service as such,” he wrote a friend, “with its dead and scattered comrades, alive again and in their places. Looking back at my command through those years, what an array of splendid fellows – now, alas! no more – rise up before my mind! How they went forth to the harvest of death, as gayly as to a ball!”

References: National Archives, Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1863-1870, “Court Martial Proceedings in the Case of Goodrich, July 8, 1862”; Sanderson, “Syke’s Regulars. The Part They Took in the Gettysburg Campaign,” National Tribune, April 2, 1891; Kippax, “Syke’s Regulars. Something about Their Terrible Fight at Gettysburg on July 2,” National Tribune, Oct. 4, 1894; Shoaf, “The Death of A Regular,” sykesregulars.wordpress.com; Chase, “Gettysburg,” The Gettysburg Papers, Vol. II ; Reese, Sykes Regular Infantry Division, 1861-65; Abbot, From Schoolboy to Soldier: The Correspondence and Journals of Edward Stanley Abbot, 1853-1863; Zogbaum, “The Regulars in the Civil War,” The North American Review, July 1898.

Charles T. Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

2 thoughts on ““How They Went Forth to the Harvest of Death”: A concise account of the U.S. Regular Infantry at Gettysburg”

Comments are closed.