By Kurt Luther

Since we launched the Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) website in 2018, more than 33,000 identified Civil War photos have been added. About 20,000 of these photos were identified by museums or in reference books. The remaining, nearly 13,000 photos, were identified by CWPS users.

But how accurate are these IDs?

Anyone who has spent time on social media or on genealogy websites such as Ancestry.com and Find-a-Grave knows that misidentifications of Civil War photos run rampant in these forums. And, as I have shown in previous editions of this column, even public collections managed by professional curators and archivists are not immune from errors.

In his 2019 review of CWPS for the Journal of American History, historian M. Keith Harris noted the site’s unusual, Wikipedia-inspired editorial model. “By simply clicking on an image,” he wrote, “site users can add or change names, units, or other pertinent information without going through a verification process.” Harris saw this type of open access as “both a blessing and a curse” because contributors can add valuable information, but also misidentifications. Ultimately, he remained positive about the site’s future, but urged users to “proceed with caution.”

Harris’ comments echoed our own concerns, and those voiced by some of our users over the years. To remain a valuable resource, CWPS needed to help users better understand how photo identifications are made, in order to assess their trustworthiness and make more informed decisions. Therefore, with the invaluable assistance of our beta testers and broader user community, we took a close look at the current identification system in CWPS. In this column, I report on some of the challenges we uncovered with the previous system. I then describe the new identification process we developed, called DoubleCheck, to address these issues. I also share some early feedback from real users, including hobbyists, students and professional historians.

Challenges

Missing provenance

One issue with the previous system was that identified photos had little or no provenance information about how those IDs were determined. Photos were simply linked to soldier names and biographies. Users were not required to indicate if the ID came from a period inscription, a reference book, word-of-mouth from a family member, facial recognition or some other source. In fact, there was not an obvious place on the site for the user to provide this information even if they had it. Lacking this key information, users could not easily judge or trust the accuracy of the IDs. Furthermore, there was no easy way to tell the difference between old (already known) IDs copied from other sources, and IDs newly discovered using CWPS.

Oversimplified IDs

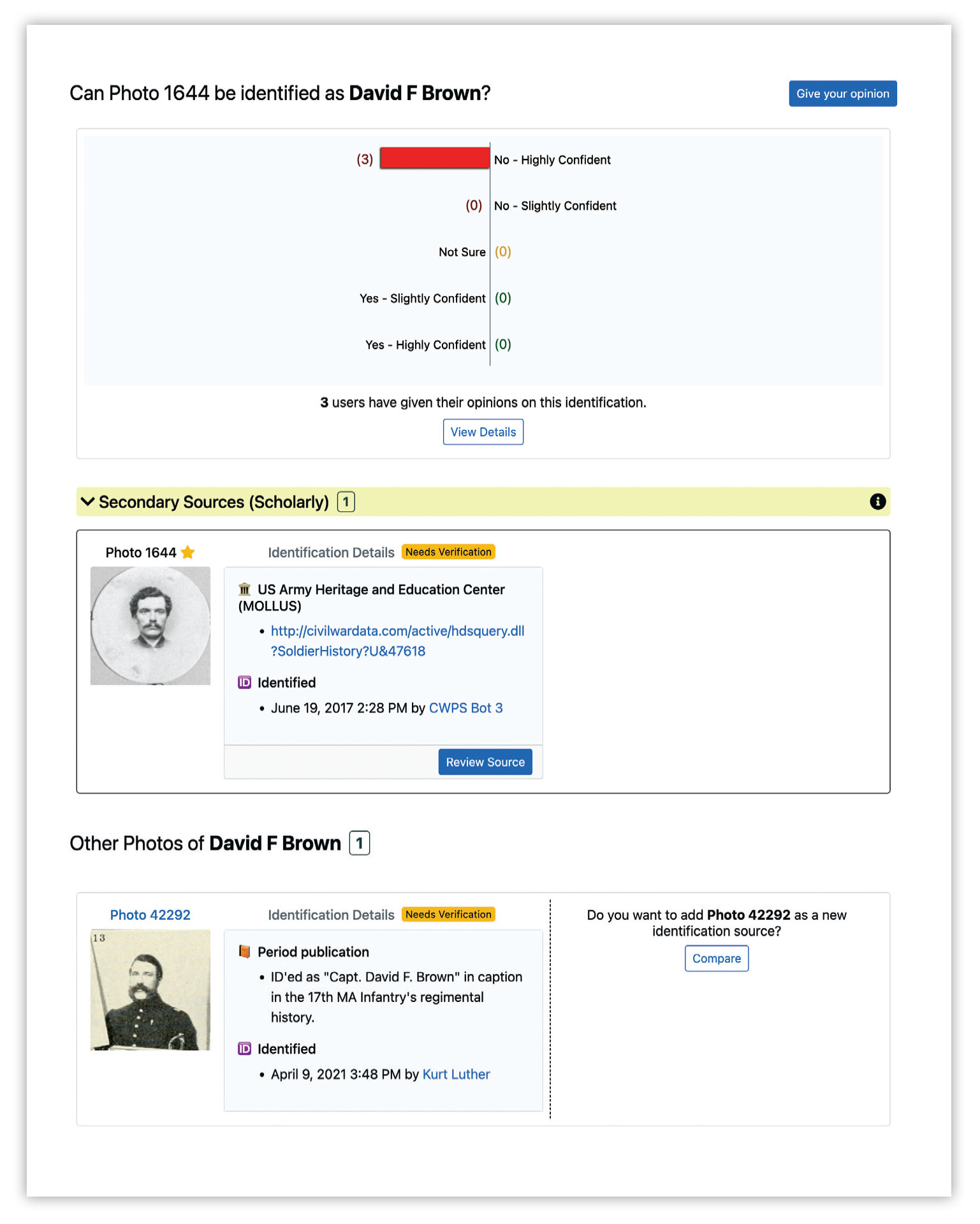

Another issue with the previous system was that it oversimplified the process of identifying a soldier photo. As any photo sleuth knows, investigations are complex, nuanced endeavors, and conclusions are not always black-and-white. The previous site only allowed users to link a photo to a name. They could not express their degree of confidence in the ID. Consequently, some users with low confidence would nevertheless make the ID, adding potential misinformation to the website. Other users would avoid suggesting a potential ID because they were not completely certain, thus abandoning a promising lead that the community could build on. If a user disagreed with an ID, their only course of action was to suggest a different ID; no way existed to simply refute the current one.

Finally, the oversimplified system conflated facial similarity with person identification. A user could conclude that two soldiers are facially very similar yet definitely not the same person. However, there was no way to capture these nuanced opinions on the site.

Differing user needs

These issues were highlighted as we talked to different types of users in our community. The previous site design catered to collectors, but proved less helpful for students and professional historians in our community. In particular, students lacked expertise in Civil War photography, but wanted to learn how to meaningfully contribute to the site. Both students and historians sought an easier way to determine which photos were reliably IDed, so they could use them for school assignments and research projects.

Solution: DoubleCheck

Design process and goals

In his review of CWPS, Harris wrote, “Some sort of verification process could potentially solve the problem. But CWPS might fall victim to accusations of ‘gate-keeper’ condescension, similar to the issues faced by historian bloggers before the medium became ubiquitous in the world of digital history.”

This concern was at the front of our minds as we considered the path forward. CWPS has always been a community-driven effort and could not exist without its users. Those users come from all walks of life—collectors, genealogists, historians, re-enactors, archivists, students, librarians, dealers and more—and bring a remarkable breadth of expertise to the site. Our solution needed to improve trust and accuracy on CWPS while retaining the “wisdom of crowds” and recognizing that valuable insights can come from anyone.

To address these issues, lead developer Vikram Mohanty and I worked with our beta testers and other members of the CWPS community to redesign the site’s photo identification system from the ground up. We call the new system DoubleCheck.

The DoubleCheck identification system relies on two key elements: provenance and community. Both elements are integrated to determine an overall quality assessment for each ID, which is clearly displayed on the photo page and available as a filter in search results.

Provenance information

The provenance component draws on our prior work, previously reported in the Summer 2020 edition of this column, understanding which identification sources the photo sleuth community considers trustworthy. To recap, we found that high-trust sources included period inscriptions, period publications (like regimental histories), and scholarly sources like reference books and museums. Medium-trust sources included facial similarity-based IDs, auction houses and dealers, genealogy websites like Ancestry.com and Find-a-Grave, and Civil War databases like HDS and CWPS itself. Low-trust sources included word-of-mouth IDs, social media IDs, and modern inscriptions.

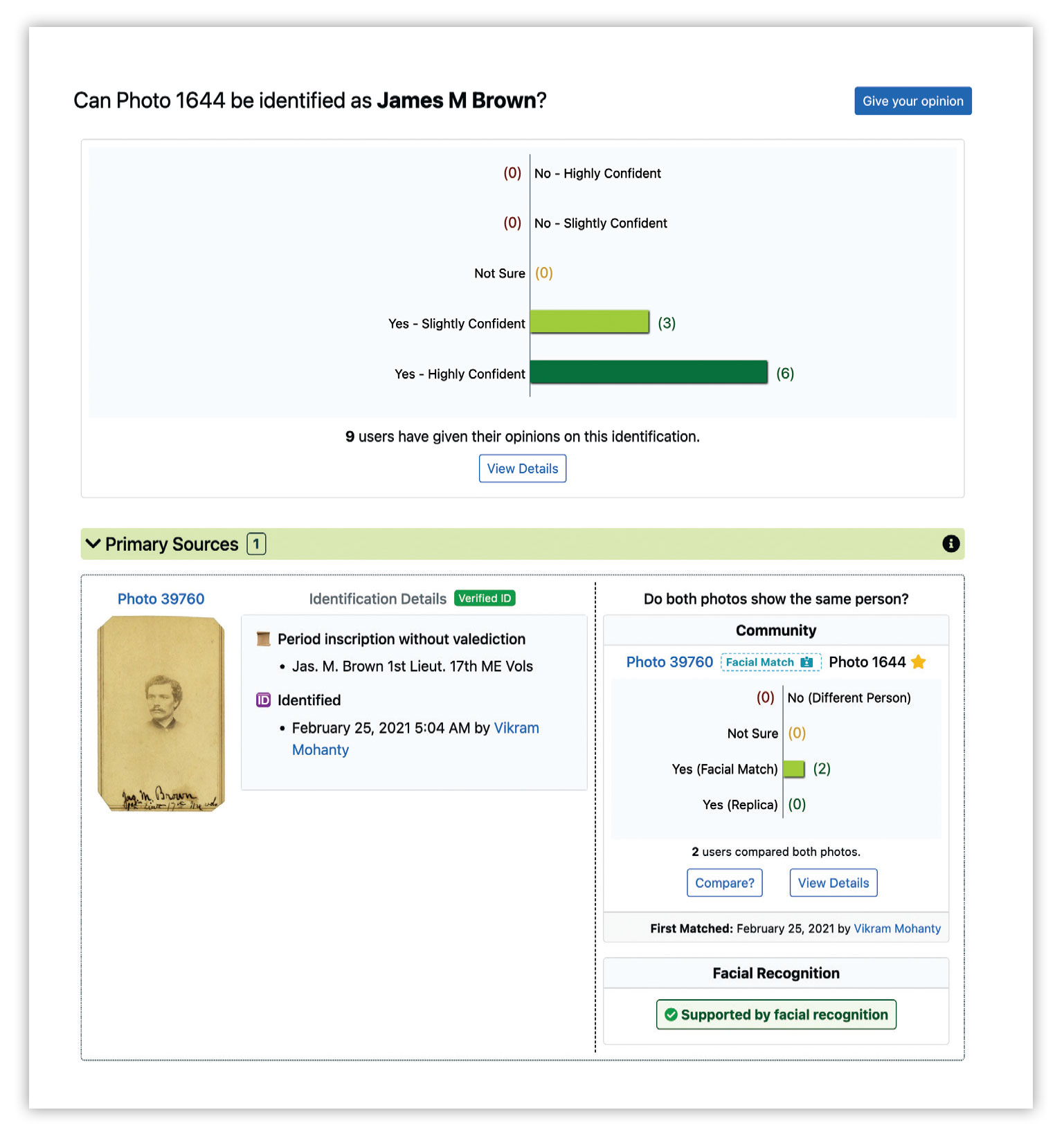

When a user identifies a photo, he now has the option to provide provenance information. Provenance includes a general category (e.g., “period inscription with valediction,” “modern publication”) and a text box for details (e.g., a transcription of the handwriting or the title and page numbers for a reference book). This information is displayed on every photo page, organized into sections for primary, secondary, and other sources.

Community voting

The community component relies on voting by CWPS users. When a user uploads a new photo to CWPS, he is asked whether the ID is already known or not. If known, he provides the provenance information and a confidence level (high, medium, or not sure). If the ID is unknown, the user has the opportunity to identify it via search results ordered by facial similarity and filtered by military service.

When the user compares a potential match to the unknown photo, he provides two votes in a two-step process. First, he compares only the facial similarity of the two photos and decides whether they are replicas (i.e., same exact view), facial match (i.e., different views of the same person), no match, or unsure. Second, he considers the broader context beyond the face (e.g., hair, facial hair, uniform, backmark, biographical details, military service) and votes on whether the two photos show the same person, i.e., an overall ID decision. Rather than a simple yes or no, the user can express his level of confidence on a scale from “Yes—Highly Confident” to “No—Highly Confident,” and elaborate on their rationale in a textbox.

If another user disagrees with a proposed identity, he can cast his vote for “No” and provide an explanation behind his decision. Additionally, the user can propose a different identity if he knows of a better candidate, but this step is optional. The distribution of votes is visualized on every photo page.

Overall quality assessment

Finally, DoubleCheck combines the provenance information and community votes to generate an overall quality assessment for every photo ID. The algorithm tries to balance the complementary strengths of these two types of verification; both are valuable but neither is infallible.

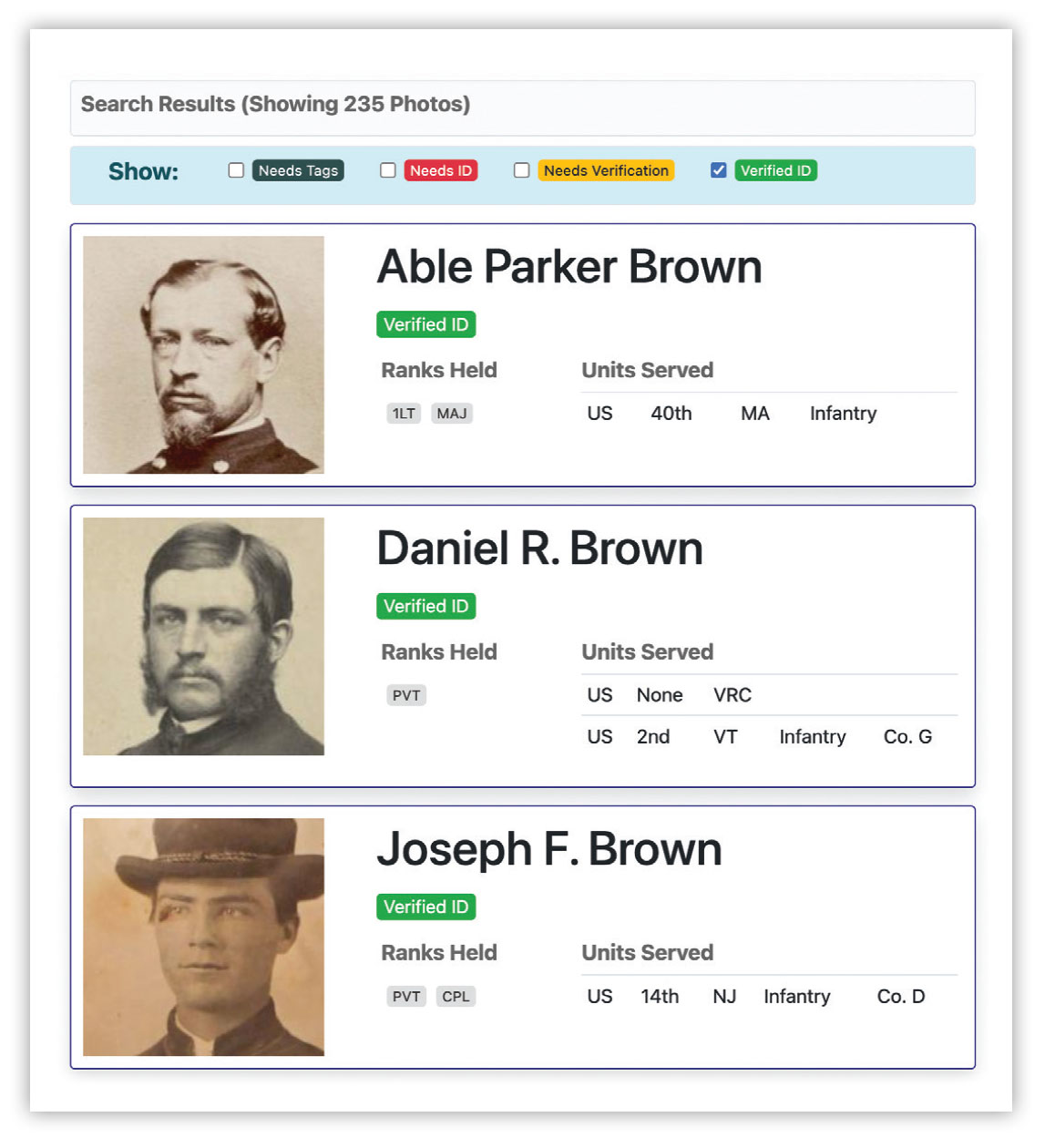

The quality assessment has four stages. A visualization on each photo page displays the overall quality assessment process, the stage that the photo is currently in, and instructions for how to advance to the next stage. Users can also filter search results to only show photos of a certain quality level.

The first stage, “Needs Tags,” is assigned automatically to newly added photos until the user tags the photo’s visual clues such as photographer information, uniforms, and insignia.

Next, the photo advances to the “Needs ID” stage until users propose at least one soldier identity for the photo. This action moves the photo to the third stage, “Needs Verification.” There are two main ways to verify a photo ID and move it to the final, highest quality stage, “Verified ID”:

- The photo is identified from a high-trust source (e.g., a primary source like a period inscription, or a scholarly secondary source like a reference book or museum), and the community votes support that ID, or,

- The photo is an exact copy or facial match of another photo that is already verified, and the community consensus agrees.

Note that there are intentional limitations in place on what types of photos can ever be verified. All verified photos must be identified using a high-trust source and have supportive community votes, or be visually matched to another photo fulfilling those criteria. Photos with only medium- or low-trust ID sources, such as social media or word-of-mouth, cannot be verified until they gain at least one additional, high-trust source. As a check against ballot stuffing, community votes alone can never verify an ID; some period evidence or scholarly source is also required. Recognizing that even these sources can occasionally be in error, however, community votes can dispute them.

Evaluating DoubleCheck

We recruited 15 participants to test the ideas behind DoubleCheck. There were five Civil War photo sleuths with prior experience using our site, along with five history students and five professional historians, representing our three main user groups. Each participant used both the new and old systems to identify randomly selected Civil War photos, and then compare the experiences.

We were happy to see that all 15 participants, including students, historians and hobbyists, preferred DoubleCheck to the old system. Students appreciated how the combination of provenance and community helped them learn which features matter most. For example, two students initially picked wrong IDs on the old system, but after viewing the community feedback on DoubleCheck, changed their minds and chose the correct IDs.

Photo sleuths, more experienced in identifying Civil War photos, found the new features encouraged more systematic research and discouraged jumping to conclusions. For example, one CWPS power user thought a photo ID was misidentified, but after viewing the same photo in DoubleCheck, he became “about 98 percent sure that this would be the right person.”

Professional historians also preferred DoubleCheck. One historian specifically pointed to the value of the quality assessments in search results: “I think immediately seeing that ‘Needs Verification’ quite clearly and so that affirms to me that this is something in contention and that I should be cautious in looking at it.”

Help wanted

Going forward, we hope that all members of the CWPS community will benefit from DoubleCheck, which is now publicly available. As with many aspects of the website, the more people use it, the more valuable it becomes for everyone. Newly added photos will all use DoubleCheck, but we need your help to add provenance info and vote on the identifications already in the database. We have placed special buttons for tagging, identifying and verifying photos on the top of the CWPS dashboard to streamline this process.

Please take time to try out these new features. Your efforts may lead to the identification of a previously unknown Civil War soldier portrait. You will also be making the 33,000 IDs in the Civil War Photo Sleuth database more trustworthy and accurate for everyone, one photo at a time.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.