By Alison Renner

Sarah Humphrey Bustill’s name is not in the annals of the Underground Railroad. Yet, she had a direct link to it through her husband, Joseph Cassey Bustill, who grew up in Philadelphia as part of the elite African-American Bustill family, and whose members were involved in the anti-slavery movement as early as the mid-1700s.

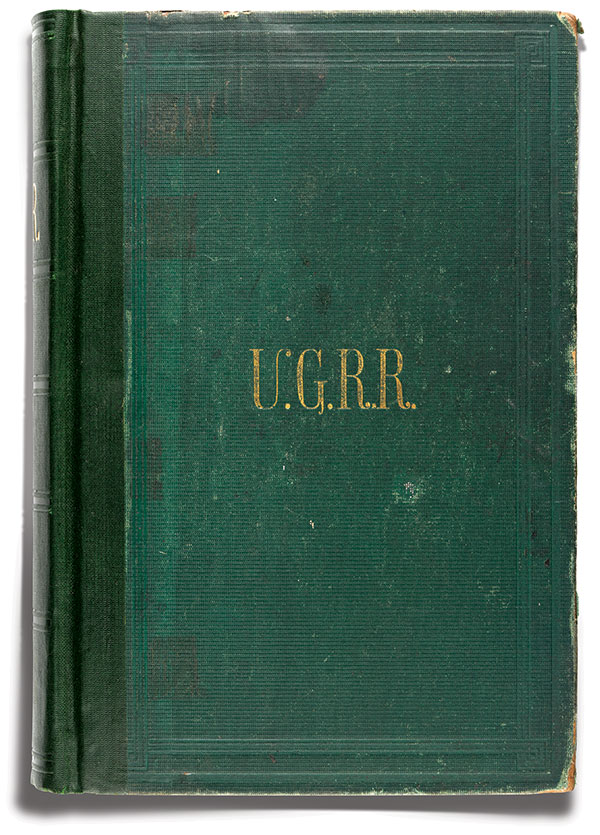

Joseph’s connection is revealed in letters to William Still, author of the landmark 1872 book, The Underground Railroad Records. Anna Bustill Smith, the daughter of Sarah and Joseph who is recognized as the first Black genealogist, noted her father’s contributions, “Many were the hairbreadth escapes and hazardous trips in those days that tried men’s souls” during the family’s time in Harrisburg in the 1850s.

Sarah and Joseph returned to Philadelphia in 1864, and worked as wig makers. Sarah died in 1891 at about age 62, and Joseph in 1895.

At some point during the early part of the Civil War, Sarah posed for this portrait in the York, Pa., gallery of Glenalvin Goodridge.

Glenalvin’s father, William, had been enslaved and gained freedom while in York, where he prospered as a local merchant. He imbued his family with abolitionist spirit and entrepreneurial drive. He also helped Glenalvin establish a career as an educator. Fate intervened when an itinerant photographer passing through town in the late 1840s offered lessons in daguerreotypy. Glenalvin, then 19, became a photographer and a teacher.

By day, the sun shone through the sky-light of his daguerreian gallery, a suite of rooms on the top floor of his father’s emporium in York. At night, the nearby family home provided a refuge for freedom seekers traveling on the Underground Railroad.

A hidden room under the kitchen bound the family in a compact for the freedom of others, despite the risk to their own their lives and livelihoods. When Glenalvin moved his gallery to his parents’ home in the spring of 1848, his white clientele were unaware that below street level the Underground Railroad moved passengers northward.

By the 1850s, Glenalvin’s younger brothers, Wallace and William, joined him in business. The earliest known portraits of them appear after the family’s move to Michigan in the mid-1860s, which begs questions: Were they not photographed in antebellum times because doing so might have been too large a risk for members of an abolitionist family? Or, were the images taken and hidden, only reappearing when safety could be ensured in ensuing decades? If so, might these photos still exist?

Glenalvin died in 1867. His brothers continued the photography business in East Saginaw, Mich., until the death of Wallace Goodridge in 1922.

Sarah’s portrait is significant. It is the only known albumen print in the carte de visite format credited to Glenalvin’s York studio, and one of five extant African-American images credited to his gallery. Perhaps most importantly, Sarah’s likeness represents the first photographic link between the Goodridge family and other documented members of the Underground Railroad.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.