Mathew Brady’s birthday is May 18, 1822, 1823 or 1824. Military Images is commemorating Brady’s bicentennial now, and we will continue the celebration with stories about the influence and impact of his life and accomplishments through 2024. To kick off our coverage, we invited nine individuals to reflect on why Brady continues to be relevant. The collected essays put Brady’s unique skills as an artist, entrepreneur, innovator, promoter, and technologist in context to the visual world we inhabit today. His work changed how we see the world, and each other.

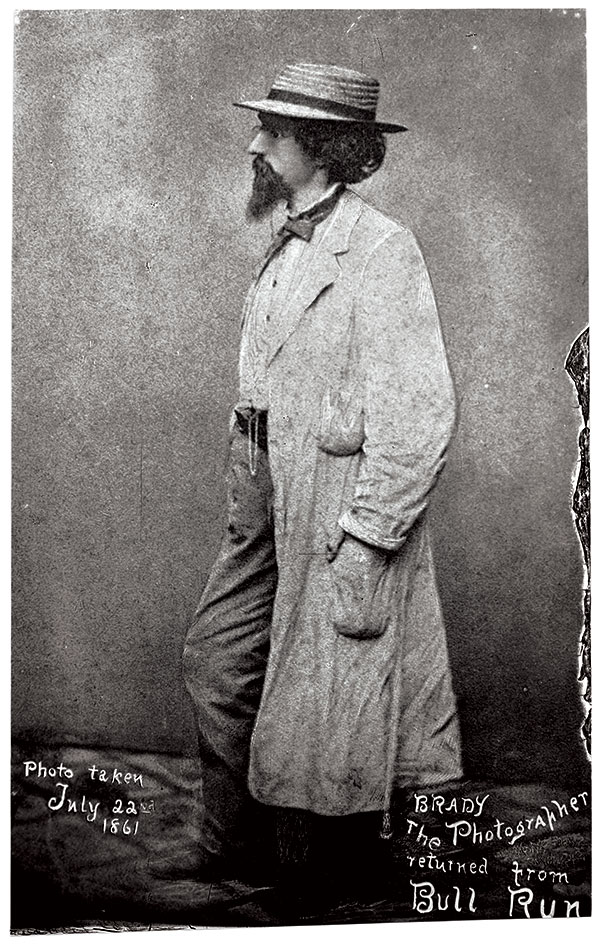

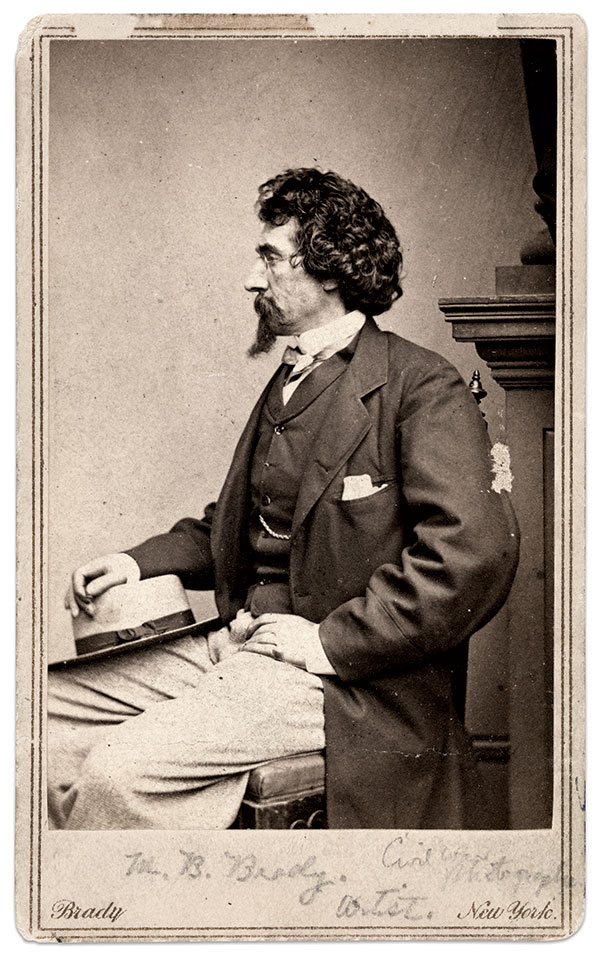

Cabinet photograph of Mathew Brady attributed to Levin C. Handy of Washington, D.C. Doug York Collection.

Today’s Visual Messages Trace Back to Brady

By William C. Davis

If anyone doubts that Mathew Brady is still relevant to us today more than a century and a half since his glory days relating to Civil War era photography, he or she need only turn on a television or a laptop or an iPhone. Every form of visual image that conveys a message today, from the evening news to the most obscure blog, traces its lineage directly back to the summer of 1861 when, as Brady himself recalled it, “a spirit in my feet said ‘go,’ and I went.”

Of course, he was not the first to focus a lens on a subject of current interest or importance, nor was he the first to produce multiple copies of such images for commercial sale. But he was incontestably the first to approach major news-making events in such an exhaustive volume, with the aim of the most comprehensive coverage possible given the limitations of time and distance in his era.

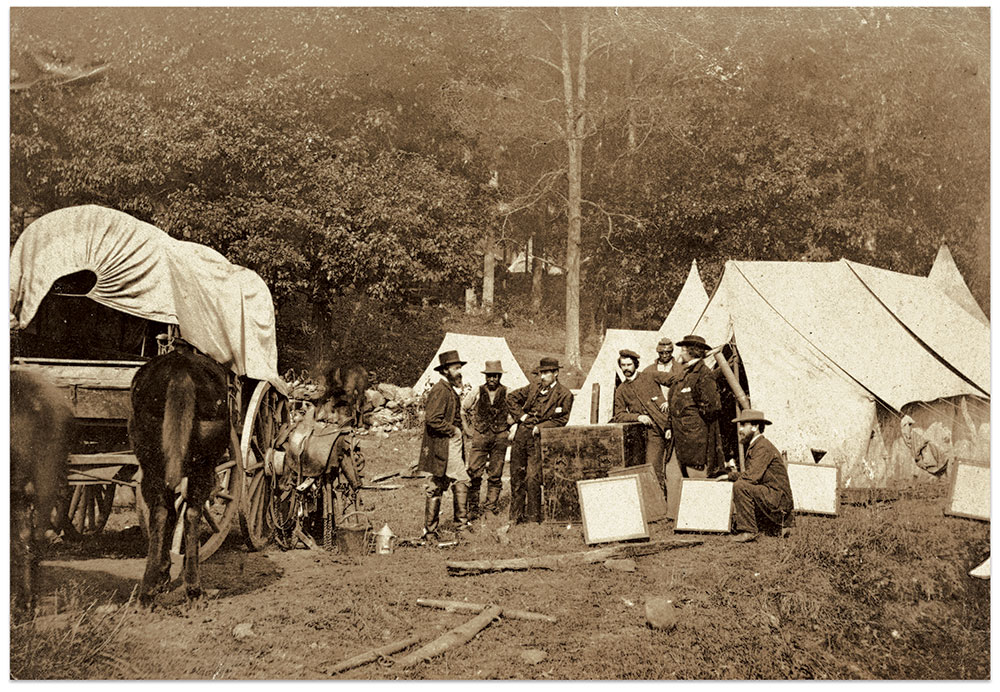

Moreover, Brady marshaled for the task an inventory of equipment and human resources vastly beyond the scale attempted by any predecessor. Perhaps dozens of stereo and quarter-plate and other cameras rode in his “what’s it” darkroom wagons with the Army of the Potomac and some of its satellites. Back in New York City and Washington, D.C., he arranged facilities for reproducing his warfront photographs and portraits in quantities governed only by sales demand.

Most important of all, he gathered to his lenses a stunning collection of able, and often outstanding, young artists. Brady’s eyesight may have been so poor by 1861 that he could hardly focus a lens, but still he had the vision to spot and nurture talent. Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, George Barnard, James F. Gibson, David Woodbury, Anthony Berger, and several others all worked for him at times during the war and saw their photographs published and circulated over Brady’s proprietary name. A few of them, including Gardner and O’Sullivan, went on to distinguished postwar careers preserving indelible scenes of American life and landscapes. It is hard not to be reminded of the great 20th century journalist Edward R. Murrow, who trained a small legion of men—and at least one woman—who became known as “Murrow’s boys” as they came to dominate newspaper and television journalism in the post-World War II era.

Above all, there was Brady’s entrepreneurial vision. The Civil War was a tragedy, to be sure. But it also presented an opportunity to a man of imagination who could see that photography, once regarded as a novelty, could be elevated into a consumer industry if it stepped outside the bounds of portraiture that previously bound it. He recognized that photography offered the public an opportunity to see and “feel” epochal events they could not view in person. The fact that Brady failed economically is irrelevant beside the transcending importance of his recognition that there was more to photographs’ potential than just what met the eye.

Historian William C. Davis has authored more than 40 books about the Civil War and edited the landmark series The Image of War: 1861-1865. He also served as editor and publisher of Civil War Times Illustrated.

War Photography Built on a Foundation of Portraits of Luminaries

By Ann M. Shumard

Mathew Brady’s name is most often associated with the extraordinary visual record of the Civil War produced by the team of photographers he assembled, outfitted, and sent into the field to document the conflict. While this endeavor alone would be sufficient to secure Brady’s place in history, focusing solely on this aspect of his career overlooks the fact that he established his reputation as an internationally acclaimed portrait photographer more than a decade before the war began.

A leader among the first generation of American photographers, Brady launched his Daguerreian Miniature Gallery in New York City in 1844, just five years after the introduction of the daguerreotype—the first commercially practical form of photography. He built a thriving portrait business by enticing celebrities of the day to pose for his camera and encouraging members of the public to follow their example. His portraits were distinguished by their superior quality and the artful posing of their subjects.

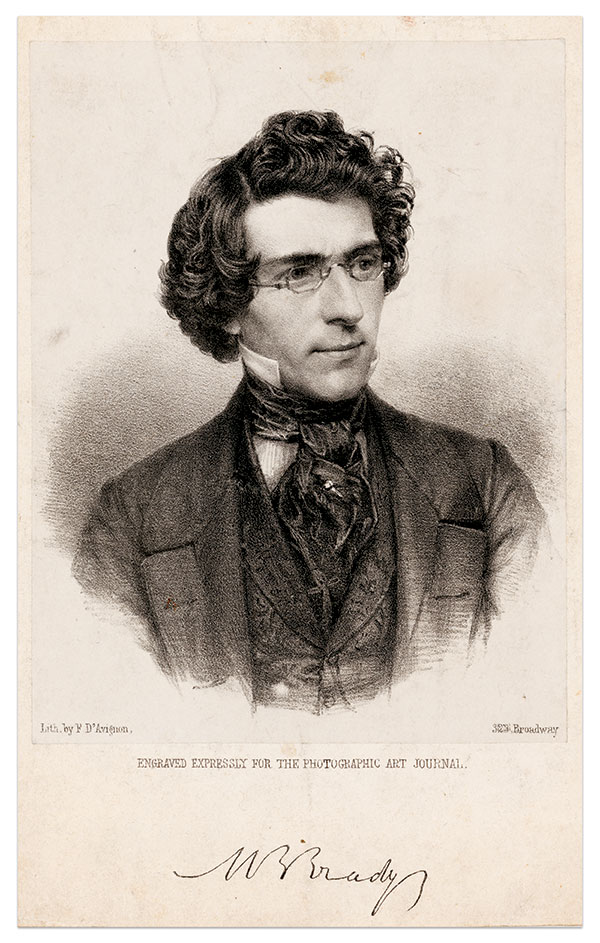

From the beginning of his career, Brady envisioned the camera as a vital tool for documenting the nation’s history through the faces of its prominent citizens. In 1850, his daguerreotypes of the famous fueled the publication of his Gallery of Illustrious Americans—a portfolio of 12 lithographs that faithfully reproduced his iconic portraits of sitters that included John C. Calhoun, John C. Frémont, Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, and Daniel Webster.

By 1851, Brady ranked among the most successful camera artists in the United States and claimed top honors for his portrait daguerreotypes at the Great Exhibition—the vast international fair presented at the Crystal Palace in London by Britain’s Prince Albert. Brady opened a new, richly appointed New York gallery in 1853, where his “large collection of daguerreotypes of eminent characters” was on display for all desiring “to witness American and European celebrities.” With the advent of illustrated newspapers in the mid-1850s, wood engravings based on Brady’s portraits of people in the public eye became standard features in these popular publications, which enjoyed wide circulation.

Luminaries from every quarter continued to flock to Brady’s New York City gallery and by 1858, his portrait enterprise had expanded to include a branch in Washington, D.C. When presidential hopeful Abraham Lincoln traveled to New York City in February 1860 to deliver an address at the Cooper Union, Republican party officials escorted him to Brady’s gallery to be photographed. The dignified portrait created by Brady played a significant role in shaping Lincoln’s public image during the presidential campaign by countering the unflattering caricatures promulgated by his detractors. Brady later delighted in claiming that Lincoln had credited this portrait as a factor in his victory at the polls.

It was largely on the strength of Brady’s reputation—built through his portrait practice and the connections it fostered in high places—that he succeeded in securing permission for his photographers to embed with Union forces at the outset of the Civil War. In this way, Mathew Brady’s portraiture laid the foundation for the indelible wartime images that remain synonymous with Brady today.

Ann M. Shumard has served as Senior Curator of Photographs for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery since 2001. During this time, she has played an integral role in expanding the photography collection, and curated numerous exhibitions, including Antebellum Portraits by Mathew Brady, Bound for Freedom’s Light: African Americans and the Civil War, and Mathew Brady’s Photographs of Union Generals.

A Debt of Gratitude Far Beyond any Technical Achievement

By Harold Holzer

Long before the rise of modern celebrity photographers Richard Avedon, Diane Arbus, and Annie Leibovitz—not to mention the giants of documentary photography like Lewis Hine, Robert Capa, and Dorothea Lange—there, bestriding and dominating both genres, was Mathew Brady. He not only mastered the arts of indoor and outdoor photography, he all but invented them (making sure that copies reached every American home). And he became a major celebrity in his own right: a showman, a pictorial journalist, and an illustrator of history as it unfolded. He was peerless.

That assessment is not meant to minimize the artistry Brady demonstrated in his heyday. He was a brilliant artist, and he accumulated the medals and honors to prove it.

But even more significantly, at his peak, Brady used his great fame to gain great access: to important people who flocked to pose at his New York and Washington galleries, knowing that the results would enhance their fame (think Abraham Lincoln, visiting New York for his Cooper Union address); and to challenging plein-air environments that revealed the horrific death and destruction of the Civil War. There Brady himself often stands, in scene after scene, garbed in his white duster and signature hat, his goatee pointing upward, nearly as familiar to his audiences, now as then, as the famous men and women he portrayed. His profile and his logo came to represent a standard of accomplishment—a level of self-confidence and a reminder of entrée—that none of his contemporaries could approach.

So, even if his eyesight ultimately declined (I feel his pain); and even if he eventually left the actual picture-making to assistants, these late-career problems do not matter much to me in assessing Brady’s incomparable contribution to photography itself and to our understanding of the Civil War era. His enterprise, in both senses of that word—his daring and his entrepreneurship alike—revolutionized American photography and made “By Brady” the most respected and recognizable imprint in 19th century pictorial art.

Only in America could such a career be notched. And only in America, I suppose, where we always move forward to the next big idea, and the next rapid technology, could Brady be disrespected and discarded by his later contemporaries. I tend to believe the story Brady recounted, late in life, when he recalled a haggard, anxious Abraham Lincoln visiting his Washington studio in 1861 to sit for a series of portraits a few days before his inauguration. Technically speaking, Alexander Gardner took the photographs that day. But when an onlooker tried introducing Lincoln to Brady, the President-elect, his thoughts on secession and conflict, snapped out of his funk and merrily replied that he needed no such introduction; that Brady and Cooper Union had made him President.

In which case we owe Mathew Brady more gratitude than any technical assessment of his career could possibly produce.

Harold Holzer is one of the nation’s preeminent scholars of the life and career of Abraham Lincoln and Civil War era politics. He has authored more than 50 books and 600 articles, as well as having served on a variety of boards and appearing on numerous television programs. He currently serves as director of Hunter College’s Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute.

He Introduced Me to the Civil War

By Ross J. Kelbaugh

Like many other readers of Military Images, I have had a very personal experience with Mathew Brady throughout my life. I first became aware of him back in the sixth grade in 1960 through an issue of My Weekly Reader that set me on the path to become a consummate newspaper subscriber interested in history. On the front page was a photograph of a man with a horse-drawn darkroom wagon in front of the nation’s capitol who announced that during the upcoming Centennial he was going to retake all the Civil War photographs made by Mathew Brady.

As part of the Centennial Generation, I consumed the books that flooded the nation with his photographs, and those of people who worked for him, that brought to life that distant era. Brady introduced me to the cast of actors who became my friends and to scenery that I would visit in this national drama some one hundred years earlier that had ignited my imagination. The first carte de visite I came across emblazoned with “Brady” became part of my nascent Civil War collection though I had no idea what the name was for these cheap card photographs found in antique shops.

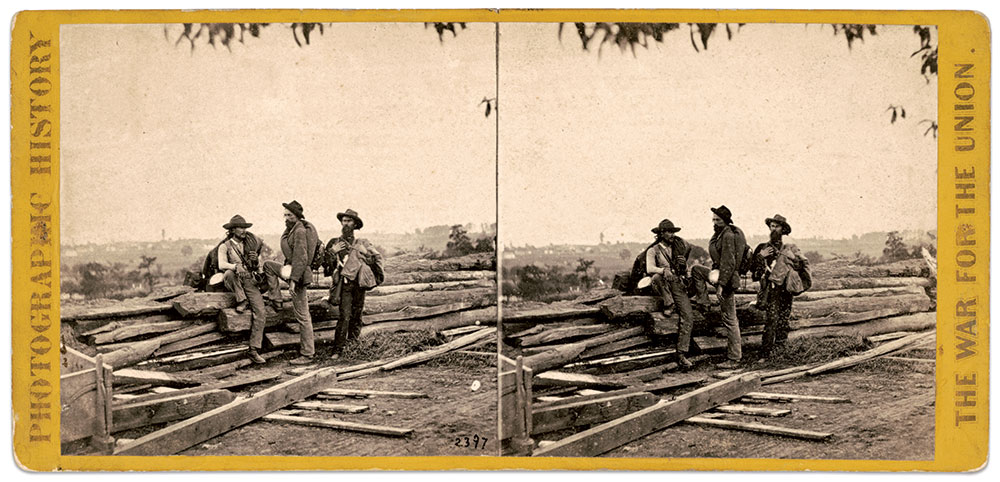

Most MI readers probably have a particular favorite among Brady’s catalog. Mine has been the Anthony stereoview of the three captured Confederates at Gettysburg, which I added to my collection for study. (Ever notice the bandage on the little finger of the soldier in the middle?) We see the studio portraits of those Southerners as they recorded themselves bravely in the armor of their cause, but what did they look like in the field? Brady’s photographs of these three “secesh” are among the few that give us a glimpse of their reality. Those photographs of the human carnage after the battle give us another perspective to be studied by today’s collectors and living-history enthusiasts. These images shocked audiences of his time and were the first I had ever seen of dead people.

I came to admire this man as I learned more about his life. I particularly appreciated how a successful gallery owner and photographic artist took it upon himself without any government support to commit his own resources to take on the daunting task of going out into the field to record this national calamity. He faced logistic challenges that are easy to forget today with the ease of the digital medium at our fingertips. And then to have those glass plates relatively unappreciated after the war when Congress had to be begged to purchase them. The amazing thing is that most people today have not yet fully appreciated his achievement since many of the views were taken in the stereo format and are still most widely viewed in only two dimensions. Perhaps virtual and augmented reality will make it possible for someone like Ken Burns to bring those 3-D photographs to the masses renewing interest in what some of us have so long cherished. This will further enhance the appreciation of Mathew Brady, who helped to visually preserve the price that this nation paid for union and freedom.

Career educator Ross J. Kelbaugh has had a passion for collecting and researching early American photographs since childhood. Born and raised in Maryland, he is focused on images of Baltimore and African Americans. His publications include Introduction to Civil War Photographs and Introduction to African American Photographs, 1840-1950.

Innovative Use of Photographic Materials to Achieve a New Vision

By Rachel K. Wetzel

Mathew Brady was revered for his stunning daguerreotype portraits and for pioneering photography during the Civil War. However, it was his overall vision of how photography could be used as a powerful tool to not only visualize a narrative, but also to change the way we absorb information and current events that remains relevant to this day. In an era where portrait photography was cemented in personal reflection, Brady decided to turn his camera outward—not to the static landscape, but to capture the essence of the conflict that plagued American society at the time. Being isolated from the men who fought in the wars, the public had no sense of the actual severity of wartime conditions. Brady, with his team of photographers, delivered candid and often barbaric images of the realities of the battlefield. Prior to this, photography was primarily used to present the subject in the best light: people dressing in their finest outfits to pose delicately in front of the camera. While Civil War troops were also photographed in this manner in studios and in military encampments as they entered the war, some soldiers were later seen amongst the dead bodies in images like those taken after the battle at Antietam. This starkly contrasting use of photography is the real impact that Brady contributed. Even though civilians were not seeing these images in newspapers the way we consume the news today, the photographs that were captured in the field helped Americans to comprehend the gravity of the war and continued to allow historians to interpret the events that happened in ways that could not have been done before the advent of photography.

This new photographic vision was not possible a few decades earlier during the Daguerreian era, for that medium would not allow for the conditions necessary to shoot on the battlefield. It is important to recognize the impact of the collodion negative and Brady’s foresight on how it could be used to advantage. While most photographers saw collodion as a less-expensive, time-saving alternative to daguerreotype portraiture, the handful of operators Brady chose were using the collodion medium outdoors to capture the construction of America leading up to the Civil War. These men arrived at the assignment having ample experience with outdoor photography. They used the traditional wet-plate medium when appropriate, but more often relied heavily on the collodion dry-plate negative, which could be prepared indoors ahead of time and developed upon return from a day of shooting. Wet-plate was not suited for intolerable weather conditions: Hot temperatures caused the viscous collodion to dry too quickly, humid environments affected adhesion upon pouring it onto the glass plate. Wet-plate also required immediate development, which was dangerous to attempt in an active setting such as the war. Brady’s relevance doesn’t lie solely in his documentary vision. It also lies in his innovative use of the photographic materials available to him and his photographic operators, which allowed him to change the way we take photographs to this day.

Rachel Wetzel lectures and writes frequently about the technical history aspects of 19th century photography and is the primary investigator of the project team responsible for the Robert Cornelius Daguerreotype Database Project. She is a Senior Photograph Conservator at the Library of Congress.

Remarkable Entrepreneurial Instincts Propelled Brady’s Artistry

By J. Matthew Gallman

When we think about the history of the American Civil War, it is easy to imagine that the pieces that fell together during those four years were destined to occur in precisely that order. In truth, all sorts of technological, military, and economic developments might have been different had the war broken out in 1832, or perhaps in 1876. That observation is nowhere more true than when it comes to Civil War photography. As chance would have it, the form and accessibility of small portrait photographs (especially cartes de visite) evolved tremendously in the decade before the war. Meanwhile, glass-plate negative processes evolved to a point that intrepid photographers could take their studios on the road. The technology changed dramatically, setting the stage for the first truly photographed war.

Brady was only one of these energetic portrait photographers, but he looms largest in our historic memory

Then there is Mathew Brady. We associate Brady with many of the crucial innovations in war photography and many of the war’s great images. Even before the firing on Fort Sumter, Brady and his partner Edward Anthony had developed an impressive line of reproduced photographic portraits. Soon consumers and collectors were buying up fashionable scrapbooks, filling them with cartes de visite of generals, politicians, authors, and actors. Even while newspapers were filled with tales of horrors from distant battlefields, the pair helped construct a new sort of fame in the form of inexpensive, collectible portraits.

Brady also developed a line of his own numbered portrait photographs. His camera captured Abraham Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, and many of the luminaries of the day. But he also photographed the less famous, who came to his studio to have their image produced. Here again Brady showed his entrepreneurial instincts, tapping into a burgeoning demand for both personal portraits and images of emerging celebrities. It is no exaggeration to suggest that Brady’s entrepreneurial energies helped create the small cartes de visite as a means of creating and celebrating fame among the noteworthy, while also—in very different ways—promoting the democratization of portrait photography. Ordinary soldiers and civilians, white and black, found their way to photographers’ studios to get that precious portrait taken. Brady was only one of these energetic portrait photographers, but he looms largest in our historic memory,

Finally, there are the scores of historic battlefield photographs offering their unique perspective on the Civil War. The new technology did not allow for the action shots that fill history books from later wars. But photographers who took their craft to the camps and battlefields found opportunities to capture the war’s impact in new and often horrific ways. Photographic series from Antietam and Gettysburg featured memorable military portraits as well as grim photographs portraying fallen soldiers. Here again we find Brady the artist and the entrepreneur. In fact, a score of intrepid photographers plied their craft on these and dozens of other battlefields, but only a handful of names are recalled by any but the experts. Many of the best worked for Brady, who took pains that his name would appear on photographs created by his employees. Some of these other photographers, most notably Alexander Gardner, eventually broke with Brady and distributed their photographs under their own names. Still, in the collective memory Mathew Brady remains known for battlefield photographs, even if he should be best known for his entrepreneurial instincts.

Historian Matt Gallman has authored numerous books about 19th century and Civil War America. He also co-edited, with Gary Gallagher, Lens of War, a collection of essays by historians about how they were affected by a single Civil War photograph. He teaches at the University of Florida’s Department of History.

Getting Beyond the Branding Hype

By Bob Zeller

No name resonates like Mathew Brady when it comes to the photographs of the Civil War. If you know nothing else about Civil War photography, you’ve probably heard his name.

In fact, if you relied on certain books, you’d come away thinking that Brady took every photograph of the war. On the other hand, some published works assert that Brady took no photographs at all because his eyesight was too poor to operate the camera.

Brady had an obvious solution for his poor eyesight. He wore glasses. But what are we to make of his legacy? Is Brady overrated? Did he steal the spotlight from his staff photographers, denying them credit and taking it all for himself? Did he take every Civil War photo or none at all?

The answer, I tell folks, lies somewhere in the middle. But after more than 40 years researching and writing about Civil War photography, particularly the documentary photographs and stereo views, I believe Brady deserves every bit of the distinction he has.

There were many other great Civil War photographers: Alexander Gardner most notably, but also Timothy O’ Sullivan, George Barnard, James Gibson, Andrew J. Russell, T.C. Roche, David Woodbury, Anthony Berger, Jacob Coonley, and, in the South, George S. Cook, Osborn & Durbec, A.J. Riddle, and Richard Wearn.

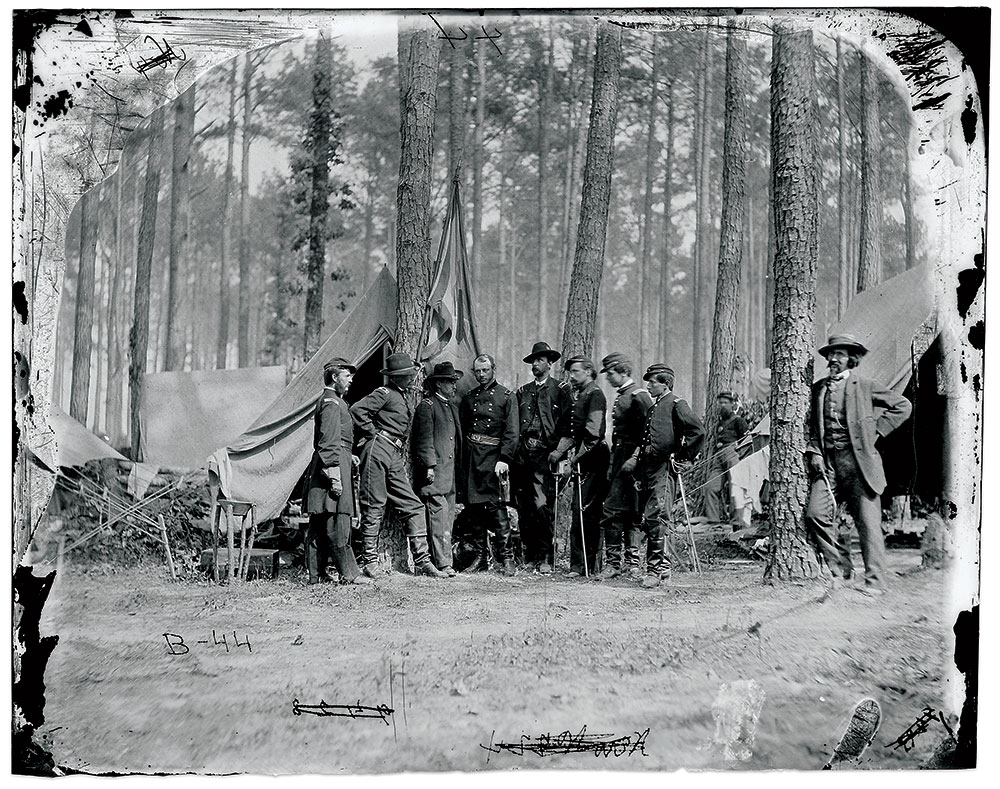

And that’s just skimming the surface. I could fill this page with names of photographers. Each division of the Army of the Potomac had its own approved photographer and assistants. The army had a total of 32 approved photographers and 65 assistants in 1865, mostly engaged in taking soldier portraits. The Cavalry Corps alone had eight photographers. Even Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters had its own approved photographer. His name was Mathew Brady.

Long before the Civil War, during the earliest years of photography—the silver-plate daguerreotype era—Brady had established himself at or near the forefront of the country’s leading photographers. He set himself apart by actively seeking famous people for sittings at his lavishly appointed New York City gallery, where he displayed their portraits. In 1850, he produced The Gallery of Illustrious Americans, an elegant book with steel plate reproductions of daguerreotypes.

When the little-known Western politician Abraham Lincoln came to New York City in February 1860 for what amounted to his national coming-out appearance, he had his choice among dozens of photographic studios. Lincoln went to Brady’s gallery. The carte de visite sold by the thousands and helped popularize the country lawyer as he vaulted to the presidency.

Brady’s reputation as the greatest Civil War photographer was more than branding hype. He went into the field at some point during every year of the war. He was personally responsible for getting the finest photographs of Gen. Robert E. Lee in uniform in 1865 and the best camp images of Lt. Gen. Grant in 1864. His gallery was responsible for the first photos of the Bull Run battlefield, images of the Peninsula Campaign, the shocking photos of the dead of Antietam, striking scenes of the Gettysburg battlefield and photos of the 1864 Virginia battlefields.

They would all come to be known as “Brady photographs,” as would many others he had nothing to do with. But contrary to myth, he did not deny credit to his staff photographers. In fact, he allowed his photographers to copyright their own images and put their own names in the copyright line that appears below images.

Did Brady himself ever actually operate the camera? Probably not very often. “Think of Brady as Steven Spielberg,” I tell folks. “A Brady photograph is like a Spielberg movie.” Brady may not have worked the camera and sensitized and developed the glass plates, but he was still directing the show and executing his vision. Brady clearly didn’t operate the camera in the more than 30 Civil War photos in which he himself appears. But in the act of posing, he showed that he was intimately involved in the composition of photos and in managing the process.

Brady was famously beset by chronic financial problems and bankruptcies throughout his long photographic career, which spanned about half of the 19th century. His dreams and ambitions in photography outstripped his business sense. He and his creditors may have suffered for it, but we reap the benefits.

Today, as it has been for many decades, the primary Civil War photograph collection of more than 6,000 negatives and prints at the National Archives is known as the “Brady collection” even though it also contains the work of quite a few other photographers. That the collection is named for Brady alone may in part be due to his skill at self-promotion, but if it had to be only one name, they picked the right one.

Bob Zeller is the author of The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography, the only book-length narrative detailing the accomplishments and exploits of the war’s photographers. Other books include Civil War in Depth: History in 3-D, the first book to document stereoscopic photo history of the war, and, with John J. Richter, Lincoln in 3-D. Zeller is the President and co-founder of The Center for Civil War Photography.

He Inspired a Magazine

By Harry Roach

Mathew Brady was the inspiration for Military Images. Indirectly, of course. One Christmas when I was about 12, my best friend received Divided We Fought, David Donald’s big glossy picture history of the Civil War. The photographs on its pages thoroughly entranced me. One thing led to another and another and eventually to MI.

Brady’s role in Civil War photography was akin to that of a director of a film, the person who manages cameramen and set-designers to achieve the best results. Brady also was an indefatigable promoter of his product, and that parallels the role of MI since its inception. Our fascination with the photos of an earlier era is mirrored in the magazine, and it continues to inspire and inform us.

Harry Roach founded Military Images in 1979. He served as Editor and Publisher until 2000.

On Fragile Fame and Fading History

By Mary Panzer

Who was Mathew Brady? Why do we remember him today? I used to tell my students that he was the Annie Leibovitz of his generation. Nearly 200 years ago, Brady recognized how a portrait, distributed widely, could create a new kind of fame. Roman emperors distributed their profiles on coins; European royalty multiplied their portraits thanks to painters and printmakers. Brady knew he could create fame for anyone who sat in front of his camera.

The first popular camera portraits were sparkling, magically detailed daguerreotypes, but they were produced only one at a time. Most makers stopped there, but Brady did not. He knew that magazines and newspapers travelled widely across the nation, and quickly collaborated with woodcut artists and wood engravers who copied his work onto printing blocks that could be set alongside moveable type. As a result, from 1845 onward when portraits appeared in print, the caption often stated, “From a Photograph by Brady.” (Brady also understood that fame extended to any name associated with that picture.) Brady and his sitters became America’s first modern celebrities, people whose faces were as well-known as their names. And thanks to the momentum generated by the combined force of photography, national media, and the human love of looking, we now can barely imagine a time when celebrity and fame were not the same thing.

Mathew Brady can also teach us a lot about fame’s limits. When Brady opened a new gallery in 1860, he installed portraits of the most famous people in America on the walls. He now made photographs, using glass-plate negatives which allowed him to produce many copies of a single image. Brady deliberately tied his reputation to the political leaders of the nation, locating a second studio in downtown Washington, D.C., halfway between the White House and the Capitol. In New York City he installed large portraits of Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John Calhoun, who all had recently died. Together these men were known as the Great Triumvirate, and for their contemporaries they represented the historical link to the Founding Fathers. Today if we remember them at all, it’s for the compromises the first two made through the 1840s and 1850s to preserve the Union without ending slavery. Calhoun remained slavery’s strongest supporter. (Today his name is being scrubbed from buildings everywhere.) Brady enlarged his photographs of the Triumvirate, hired painters to add color, and framed the portraits in gold, giving these men pride of place, and they are visible on a long wall in a contemporary woodcut. He called his growing collection “Brady’s National Portrait Gallery.” One reviewer declared that if all the men pictured there could assemble in a single room, there would be no need for war, which had already risen well over the horizon.

Tourists, including, in 1860, the Prince of Wales, visited Brady’s Gallery. That same year, when Abraham Lincoln sought the Republican nomination, his handlers brought him to Brady for a campaign portrait that ran as a woodcut in papers across the nation. According to Brady, Lincoln said that picture helped make him President.

By 1861, Brady realized that all the newsworthy heroes would be found at war, not in the halls of Congress, and he traveled outside his studios to photograph military celebrities in camp and on the battlefield. In the process, he and his multiple teams of cameramen became America’s first photojournalists. In 1862, men and women stood in long lines before Brady’s New York gallery to see photographs from Antietam just days after the war’s bloodiest battle. The New York Times stated, “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryard and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

Antietam cameramen Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan soon left Brady to set up a new firm. Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (published in 1866 and still available in a replica edition) includes some of the most horrible and memorable images of the war. Brady continued to create more heroic images, and his portraits appeared on the front pages of illustrated papers such as Harper’s Weekly.

Brady spent freely to send photographers to the battlefield, expecting to profit from his portraits of new heroes. But crowds were not interested in looking at pictures that recalled the war. Brady could not pay his debts. He settled in Washington, surrounded by his Portrait Gallery, where he continued to work alongside a new generation of photographers who had no ties to a painful past. He sold thousands of negatives made during the Civil War to the National Archives. In 1911, fifty years after the war began, another set of Brady’s photographs appeared in the 10-volume Photographic History of the Civil War (these images are now at the Library of Congress). Brady’s nephew Levin C. Handy eventually took over the business. In the mid 1950s, Brady’s once-valuable collection of daguerreotypes and photographs went to the Library of Congress, and the colorful portraits of Webster, Clay, and Calhoun entered the collection of the U.S. Capitol, where they still hang outside the hall where the House of Representatives meets.

Today Brady’s work reminds us how fragile fame can be and how quickly history fades from view. But it is difficult to appreciate his true importance, for we still live inside the world where fame and celebrity depend upon images, made by cameras and spread widely through the media, the world that Mathew Brady helped create.

On Jan. 7, 2021, Brady’s portraits of Clay and Calhoun appeared on the front page of the New York Times, staring above the mob that had filled that hall the day before.

The Great Triumvirate feared the possibility of events like those on Jan. 6, 2021, expressed best by Lincoln—that the nation’s house, if divided, could not stand. They might even have imagined a dark day when enemy flags would fly in the Capitol. But those old men never imagined that they would be forgotten.

Mary Panzer, historian of photography and American culture, curated the 1997 exhibit Mathew Brady’s Portraits: Images as History, Photography as Art, during her tenure as Curator of Photographs at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery. Her books and other writings include Mathew Brady and the Image of History. She is co-author of the prizewinning volume, Things as They Are: Photojournalism in Context 1955-2005.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.