By Gene Eric Salecker

Some photographs achieve iconic status because they are haunting and immediate. Marines raising the U.S. flag during the Battle of Iwo Jima. Jack Ruby shooting President John F. Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. A passenger jet only a heartbeat away from crashing into the Twin Towers on 9/11.

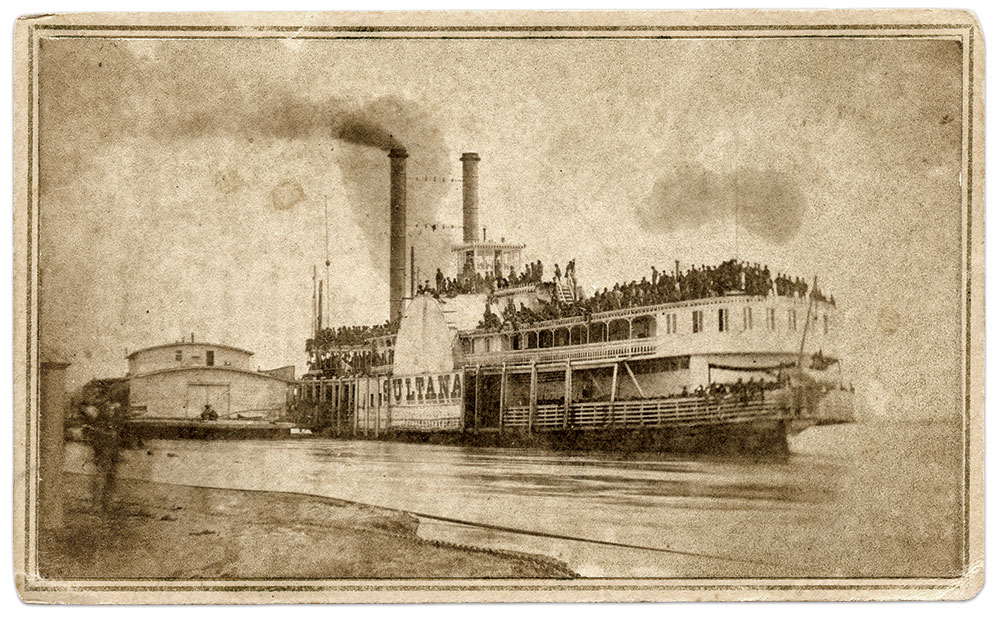

Add to this list the view of the steamer Sultana crowded with Union veterans a day before most of them perished after the vessel exploded and sank.

The photographer who captured the scene, Thomas W. Bankes, is all but forgotten. He practiced his craft in Arkansas through the Civil War, Reconstruction, and after in the remote southeastern section of the state. Through his camera lens he documented all aspects of his time there. For almost 40 years he reigned as one of the premier photographers in the South, taking images, penning articles, and even writing poetry.

Born in England about 1830, Bankes immigrated to the United States before the Civil War. The 1860 federal census lists him as a painter living in Helena. In an advertisement published in Helena’s Southern Shield newspaper in January 1860, he offered his services as a “House, Sign & Artistic Painter, Imitator of Fancy Woods and Marble, Plain and Decorative.”

In early 1862, Bankes set up a photography studio in Helena’s Post Office Building, which had housed the United States Customs Office. In February, he advertised that his new gallery over the post office was “now in full blast,” and claimed his skylight was the largest and best in the southwest, allowing portraits to be made in all weather.

Months later, on July 12, 1862, federal forces under Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis marched into Helena, the only Arkansas port on the Mississippi River. Soon labeled “Hell in Arkansas” due to overcrowding, unhealthy conditions and climate, most occupying soldiers dreaded their duty in the small riverfront community that emerged as a major base of operations.

Many of Helena’s residents fled the occupying troops and thousands of escaped slaves sought refuge inside federal lines. Maj. Gen. Curtis used contraband laborers to construct five earthwork fortifications, the largest being Fort Curtis on the west side of town near the base of a ridge surrounding Helena. Batteries dubbed A, B, C and D, lined the ridge at strategic points.

Bankes, with no political preference for either side, stayed in Helena and captured images of the soldiers and runaway slaves.

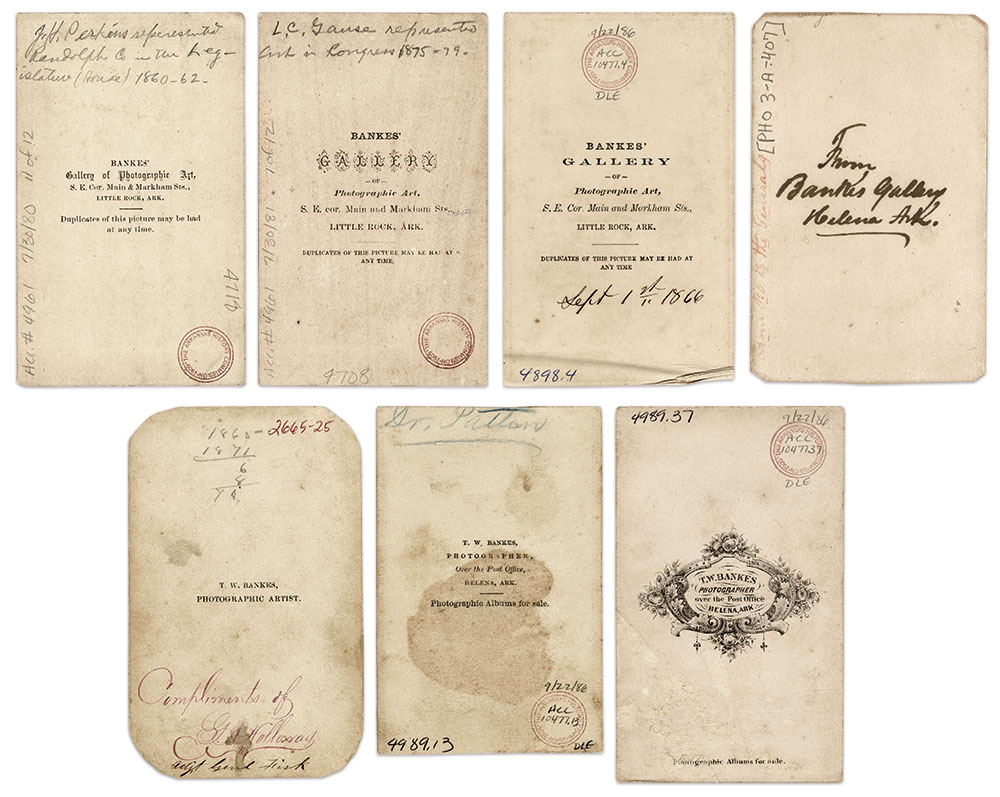

At first, Bankes used a simple back mark on his cartes de visite: “T. W. Bankes, Photographic Artist.” The second variation of his back mark was also plain: “T. W. Bankes, Photographer, Over the Post Office, Helena, Ark.” As business grew, and he became better at his craft, he designed a back mark, which showed an oval decorated with flowers and swirls. In the center he repeated the words, “T. W. Bankes Photographer over the Post Office Helena, Ark.”

Bankes assumed the role of unofficial military photographer and took a few images of Fort Curtis and the Tappan House, just beyond the fort’s western wall. Owned by Confederate Brig. Gen. James C. Tappan, high-ranking Union officers established a headquarters at his residence. The surrounding grounds, once inhabited by Tappan’s many slaves, became the site of a sprawling general hospital.

Bankes also photographed the exterior of the home of Helena resident and Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman, with Battery D on Hindman Hill behind the home.

Meanwhile, 170 miles south in Vicksburg, Miss., Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army campaigned to capture the fortress city and control the Mississippi River. As Grant’s forces surrounded and besieged the city, the Confederate commander in Arkansas, Lt. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, planned an attack on Helena to relieve pressure on Vicksburg. On July 4, 1863, Holmes led a failed three-prong attack against the 4,000-man U.S. garrison commanded by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss. Bankes took no known pictures of the battle sites.

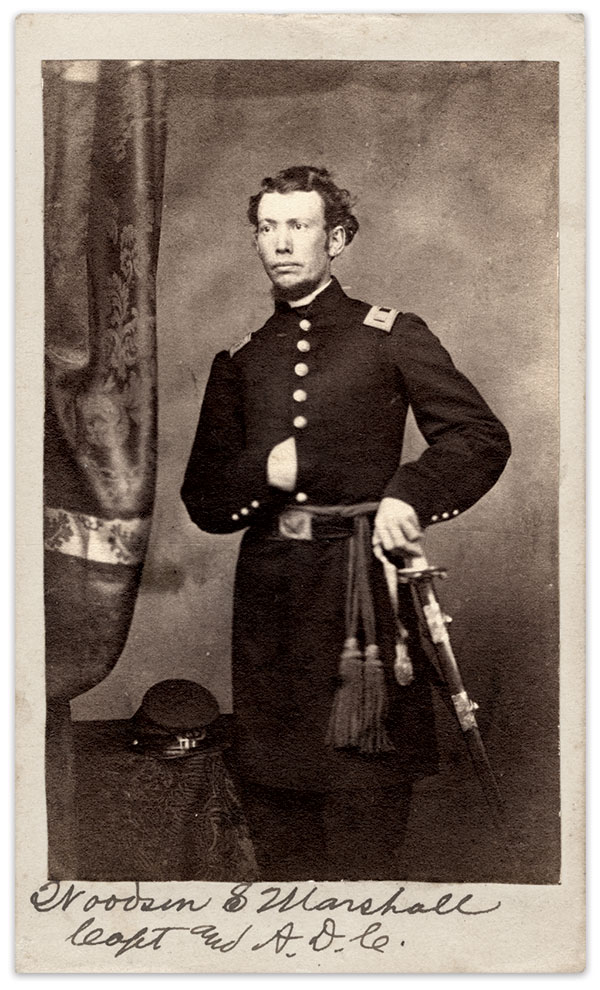

In September 1863, Brig. Gen. Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, older half-brother to Gettysburg hero Brig. Gen. John Buford, became the commander of the District of Eastern Arkansas. During his stay at Helena, Bankes took two photographs of the general, one standing alone, and one standing beside his seated wife.

After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863, many of the escaped ex-slaves residing in the contraband camps around Helena were recruited into regiments of Black soldiers. Bankes took numerous shots of white officers of those units, specifically officers of the 54th, 56th and 60th U. S. Colored Infantry, but no images of newly enlisted Black recruits have been found. Why no photos of Black men in blue have surfaced remains unknown.

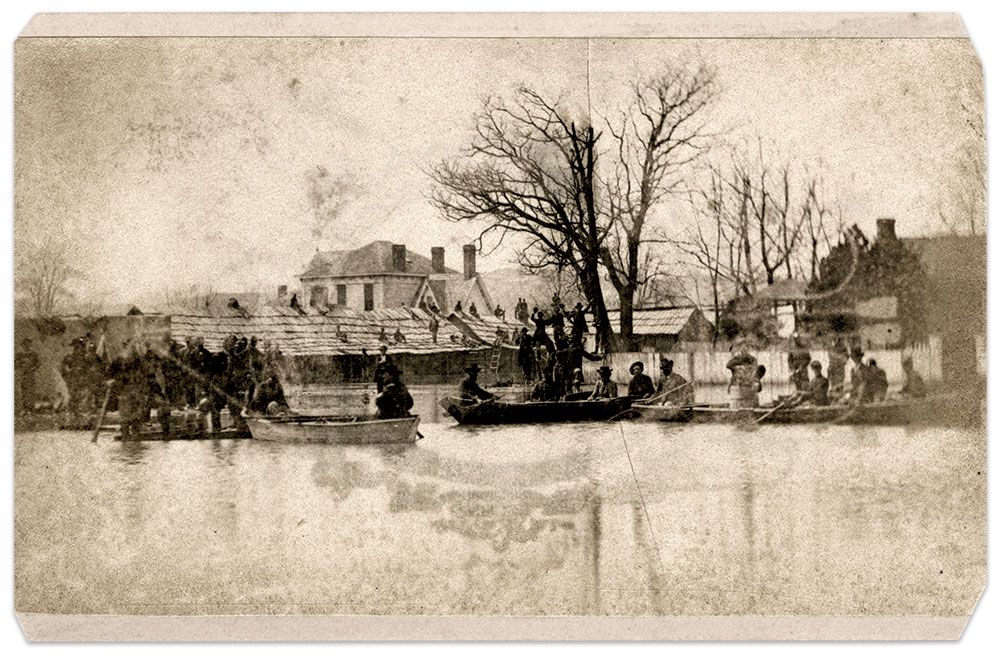

In April 1865, as war waned in the East, the Mississippi River rose and overwhelmed Helena. Bankes photographed Union soldiers passing through the flooded streets on small boats and rafts, one fitted with a mast and sail. His images showed temporary walkways made of wooden planks that reach down the center of some streets.

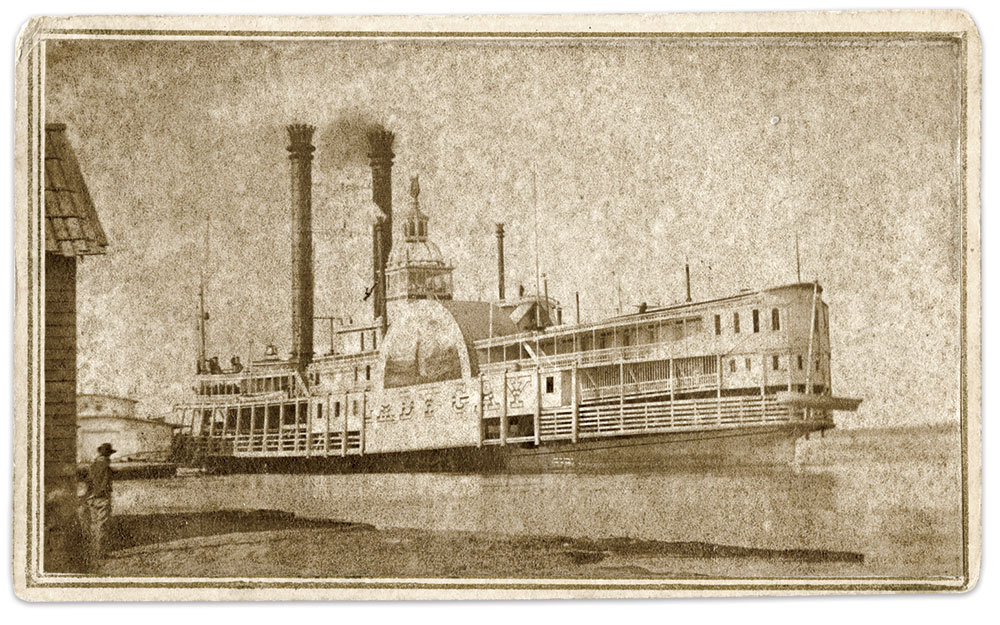

Perched on high ground near Fort Curtis, Bankes took several images showing much of the town engulfed by water. Far in the background, recognizable by the tree line along the bank of the Mississippi state line, flowed the mighty river itself. On the afternoon of April 25, Bankes set up by the river and took photographs from near the old steamboat landing. Here, he found a steamboat launched only a month earlier. Painted on the side of its large paddlewheel housing was a woman in a flowing gown, walking through a plush field. Below the figure was the name Lady Gay. Turning his camera towards the boat, Bankes looked through his lens and, before capturing the scene, may have noticed that the big steamboat carried few passengers.

The next boat that he photographed would be the opposite.

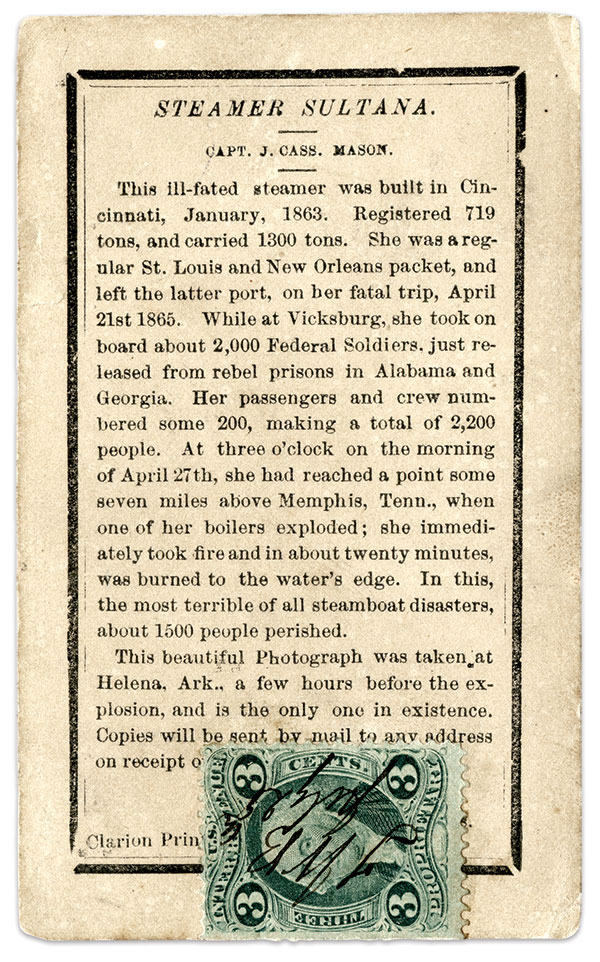

The following morning, at about 7:00 a.m., on April 26, 1865, the two-year old sidewheeler Sultana tied up to the Helena wharfboat. Almost 2,000 Union ex-prisoners-of-war congregated on board, recently released from the Confederate prisons at Andersonville, Ga., and Cahaba, Ala. Built for 100 crew and 376 passengers, 2,130 people packed its decks, including ex-prisoners, a handful of guards, civilian passengers and crew.

Bankes knew an unbelievable sight when he saw it. He took his iconic image as most of the soldiers on the Sultana stared out at the flooded streets of Helena. He had no way of knowing that within 24 hours upwards of 1,200 of the people crowded aboard the vessel would lose their lives after its boilers exploded, resulting in the worst maritime disaster in American history.

In July 1865, Bankes sold his gallery and moved to Cincinnati. Less than a year later, however, perhaps because of competition among numerous established photographers, Bankes closed the studio and moved back to Arkansas, this time setting up in Little Rock. He became an early adopter of the cabinet card format. In 1868, he sent examples of his work to the industry magazine Philadelphia Photographer. The editors remarked that Bankes’ specimens “prove him to be a very tasteful and careful poser and a good manipulator. If he is ‘away out in the country,’ as he says, his work may well put to the blush some who are much nearer to our office.”

Bankes went on to become one of the most prominent photographers of the South Central region, documenting Arkansas politicians, and producing stereoscopic views of Hot Springs. Displays of his photographs became a staple at the annual Arkansas State Fair and were recognized in art exhibitions in New York City.

Reports of his activities indicate Bankes considered himself a student of photography, always eager to learn and improve his craft. In 1872, he journeyed across the Atlantic for inspiration. One European correspondent who met him wrote in Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, “A few moments only in presence of Mr. Bankes convinces me that he is full of his profession—who but one truly alive would undertake fifteen to twenty thousand miles of travel, great expense, and much time even for the lessons to be learned in art’s highest repositories?”

The admiring author added, “His enterprise declines circumscription. Restive in his immediate region, he seeks to derive by actual contact—seeing, conversation—stopping only when there is no more beyond.”

Bankes also proved an astute scholar of photography. In a two-part story for The International magazine in 1899, he traced the origins of photography to the discovery of the camera obscura in the 17th century, and other developments that culminated in the daguerreotype in 1839. He reminded readers that the art and science of photography practiced by him, and his peers, descended not from Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, but from a fellow Brit, William Henry Fox Talbot.

Bankes concluded his monograph with a tribute to his craft: “Science invented a photographer of its own who dips his pencil in the sunbeam, and traces with unerring truth the living shadows of the passing time.”

The image of the Sultana and the rest of his portfolio exemplify Bankes’ statement.

Around 1887 Bankes moved to Chicago. He continued to tout the attributes of Arkansas, writing numerous articles about his adopted home state. He returned to Little Rock in July 1905 and passed away on March 29, 1906, of apoplexy. He was about 76 years old. Noted the Daily Arkansas Gazette, “Twenty-five years ago he was the leading photographer of the city, an artist and a writer of more than ordinary ability.”

References: 1860 U.S. Census; Southern Shield, Helena, Ark., Jan. 28, 1860, and Feb. 8, 1862; Daily Arkansas Gazette, Little Rock, Ark., Jan. 5, 1873; The International: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Travel and Literature, Chicago, March and April 1899; Philadelphia Photographer, May 1868.

Gene Eric Salecker is a military historian whose six published books include Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana: The Worst Maritime Disaster in American History (2022) and The Second Pearl Harbor: The West Loch Disaster, May 21, 1944(2014). He owned the largest collection of Sultana artifacts and memorabilia which he donated to the SultanaDisaster Museum in Marion, Ark. A graduate of Northeastern Illinois University, he is a retired police officer and retired middle school teacher currently acting as the historical consultant for the Sultana Disaster Museum. He lives in River Grove, Ill., with his wife, a rabbit, a cat, and dozens of tropical fish.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.