By Frederick C. Gaede

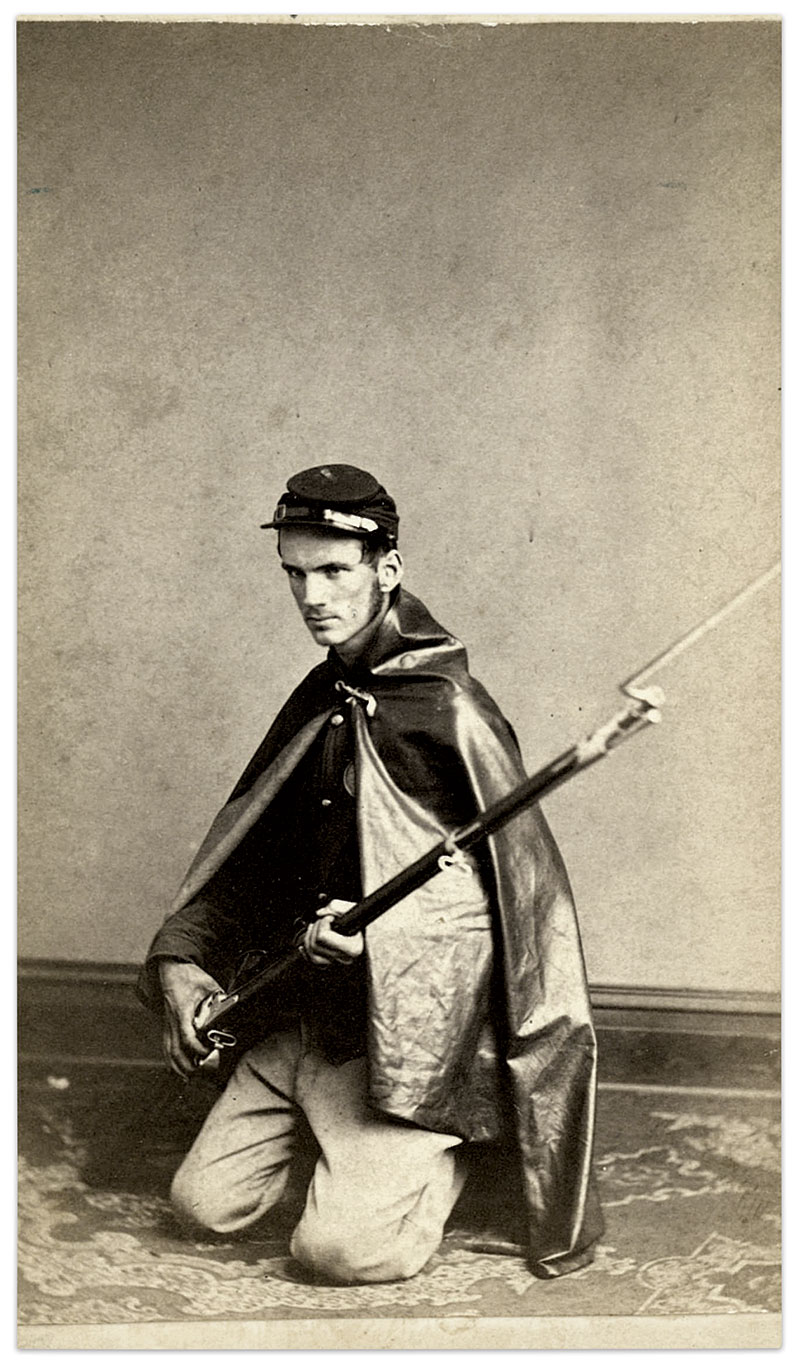

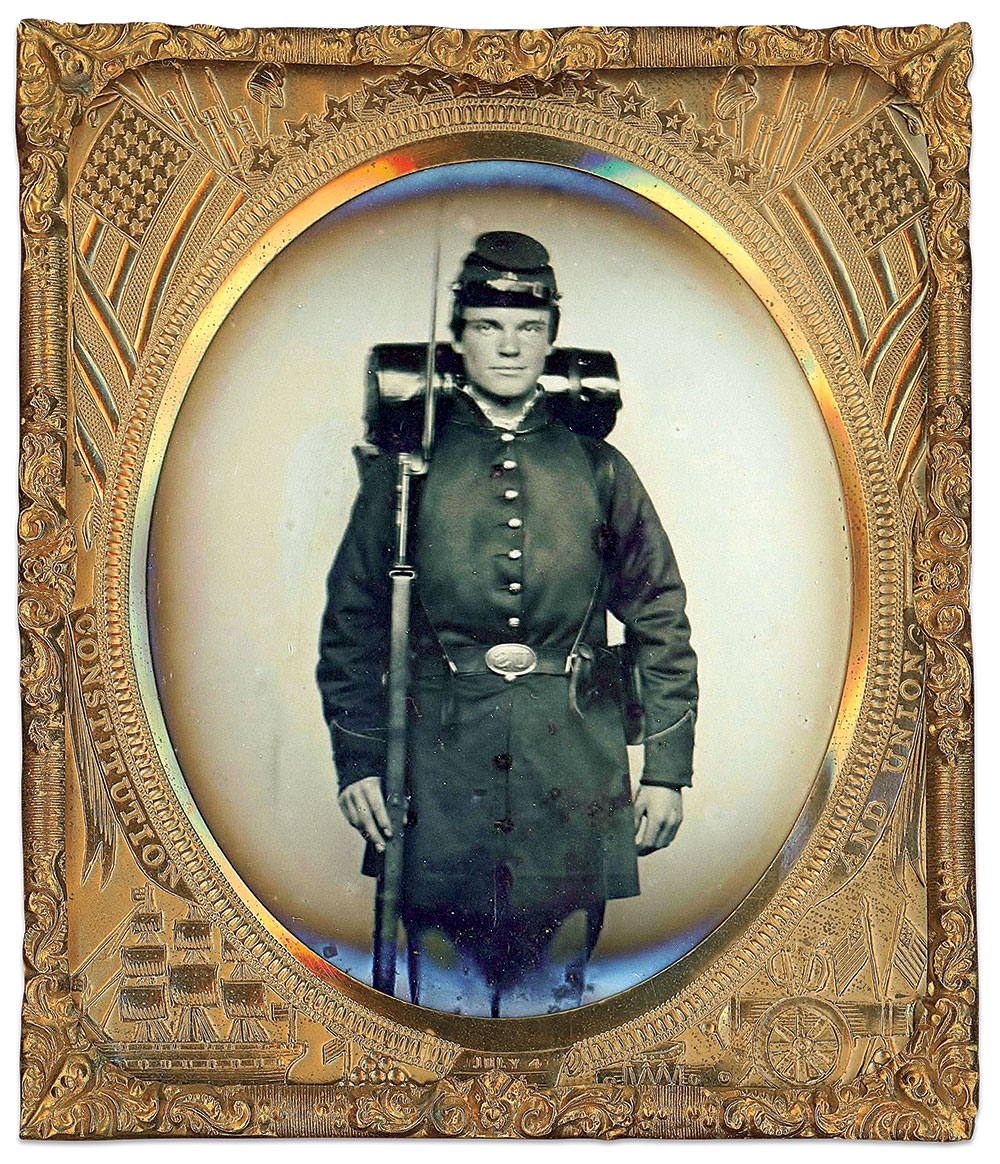

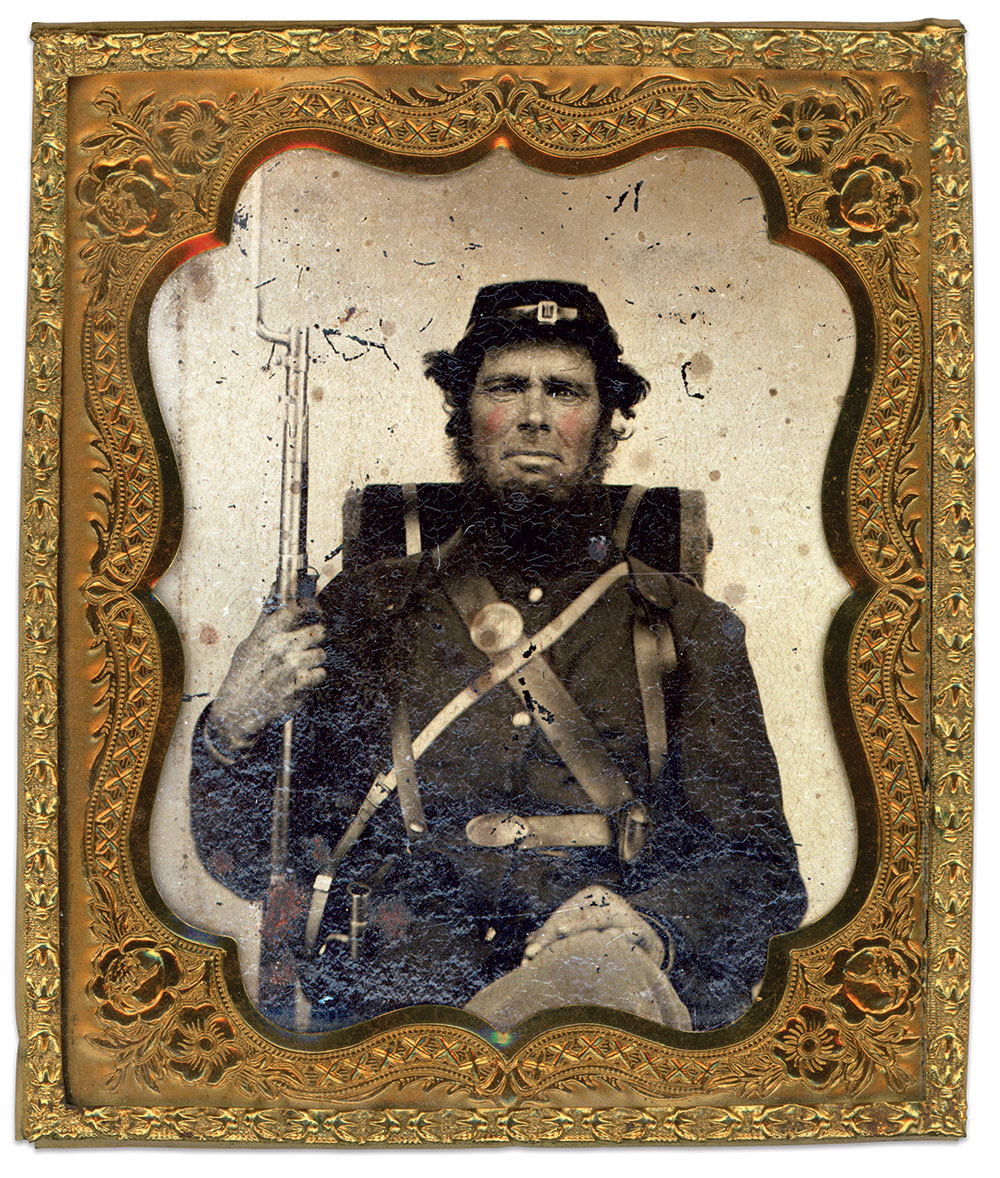

Prior to the Civil War, the Quartermaster Department provided U.S. soldiers with three items of personal protection from the elements: woolen blankets (bedding or saddle), great coats and talmas.

Blankets were issued with an allowance of one for every five-year enlistment. Great coats, first introduced in 1817 and regarded as company property reserved for guard duty or the harsh climes of the Midwest, were issued on the same schedule as blankets. Talmas, introduced in 1855 and distributed to new mounted cavalry units, were also considered company property until discontinued in 1862.

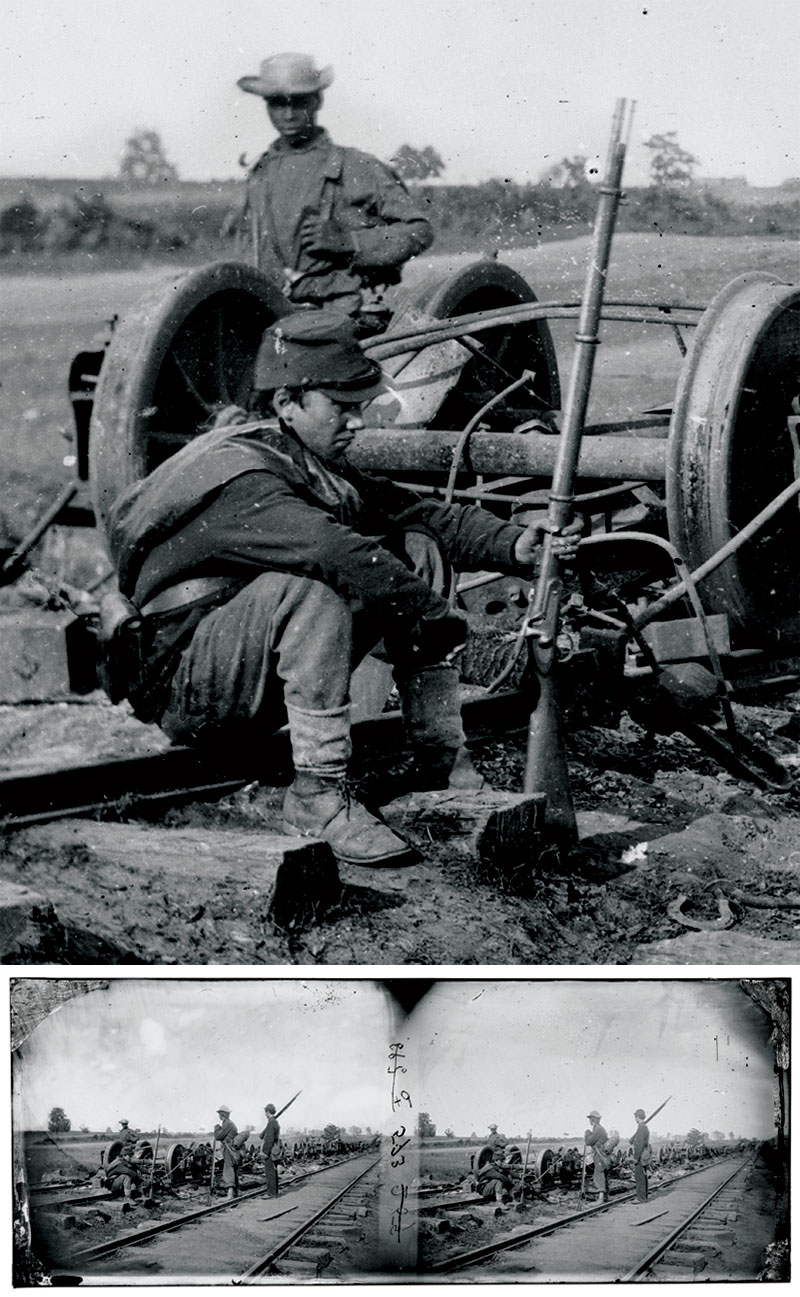

During the Civil War, the Quartermaster Department introduced ponchos and waterproof blankets to soldiers with an allowance of one per year, according to Paragraphs 66 and 67 of the Revised Army Regulations for 1863.

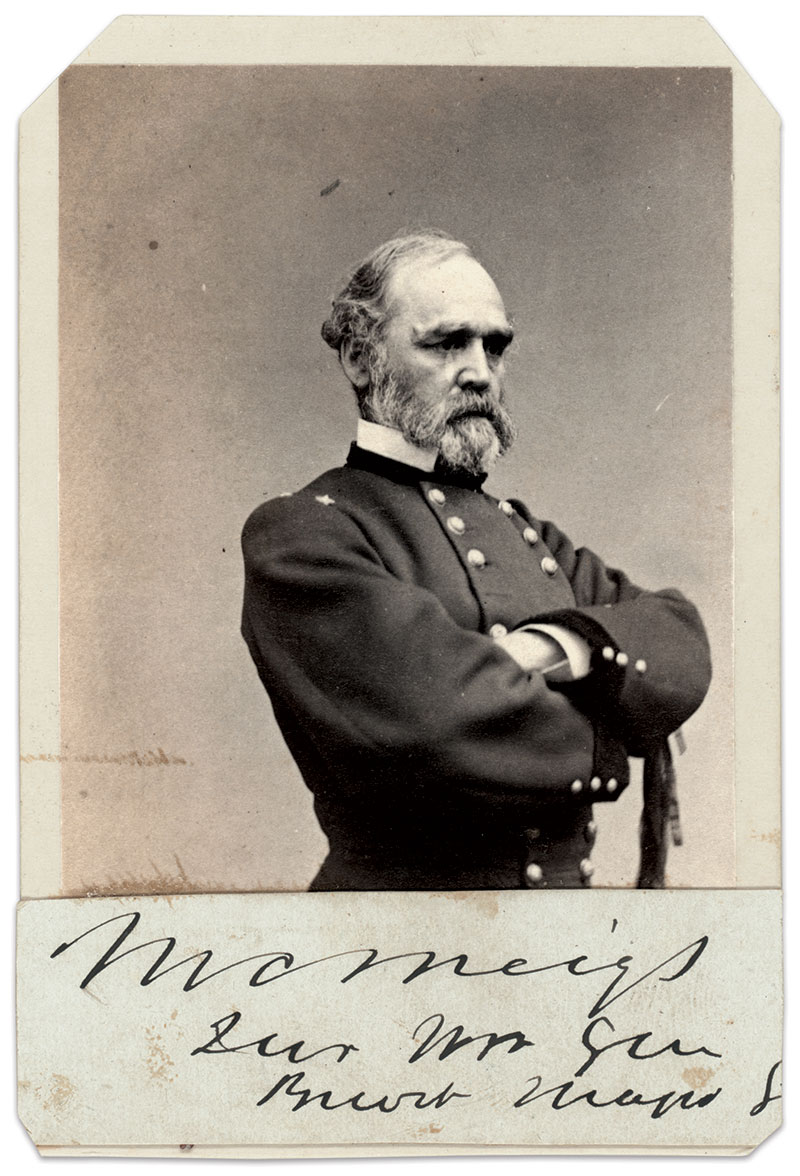

The logistics of supplying these and other items fell to Capt. Montgomery C. Meigs upon his promotion and appointment as Quartermaster General on May 15, 1861. Meigs faced a significant challenge. He had to get control and reorganize an understaffed, career-officered bureaucracy while simultaneously supplying increasing numbers of troops arriving in Washington in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s calls for volunteers.

Many volunteer units looked to the federal government to replace uniforms and equipment provided by their states under the commutation system. Meigs received requests for items not on the official allowance lists that he had no ability or inclination to replace. This included various styles of ponchos and ground cloths, especially widespread among the large number of troops from New York in the Army of the Potomac.

The composition of ponchos and waterproof blankets was also in flux. Three competing materials—gutta percha, India rubber, and painted cloth—were available, each with its own private industry backers vying for lucrative government contracts.

Ponchos + waterproof blankets = poncho tents

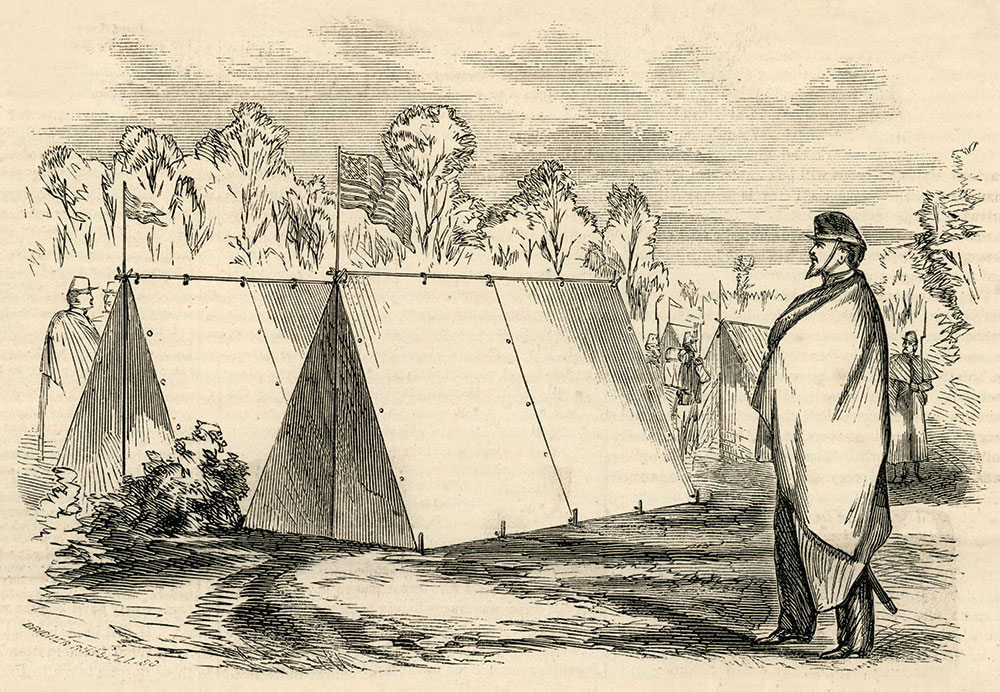

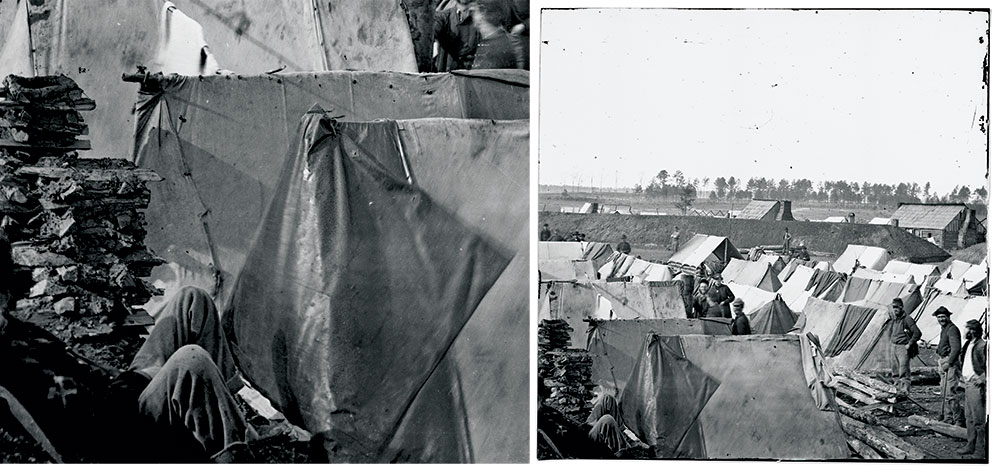

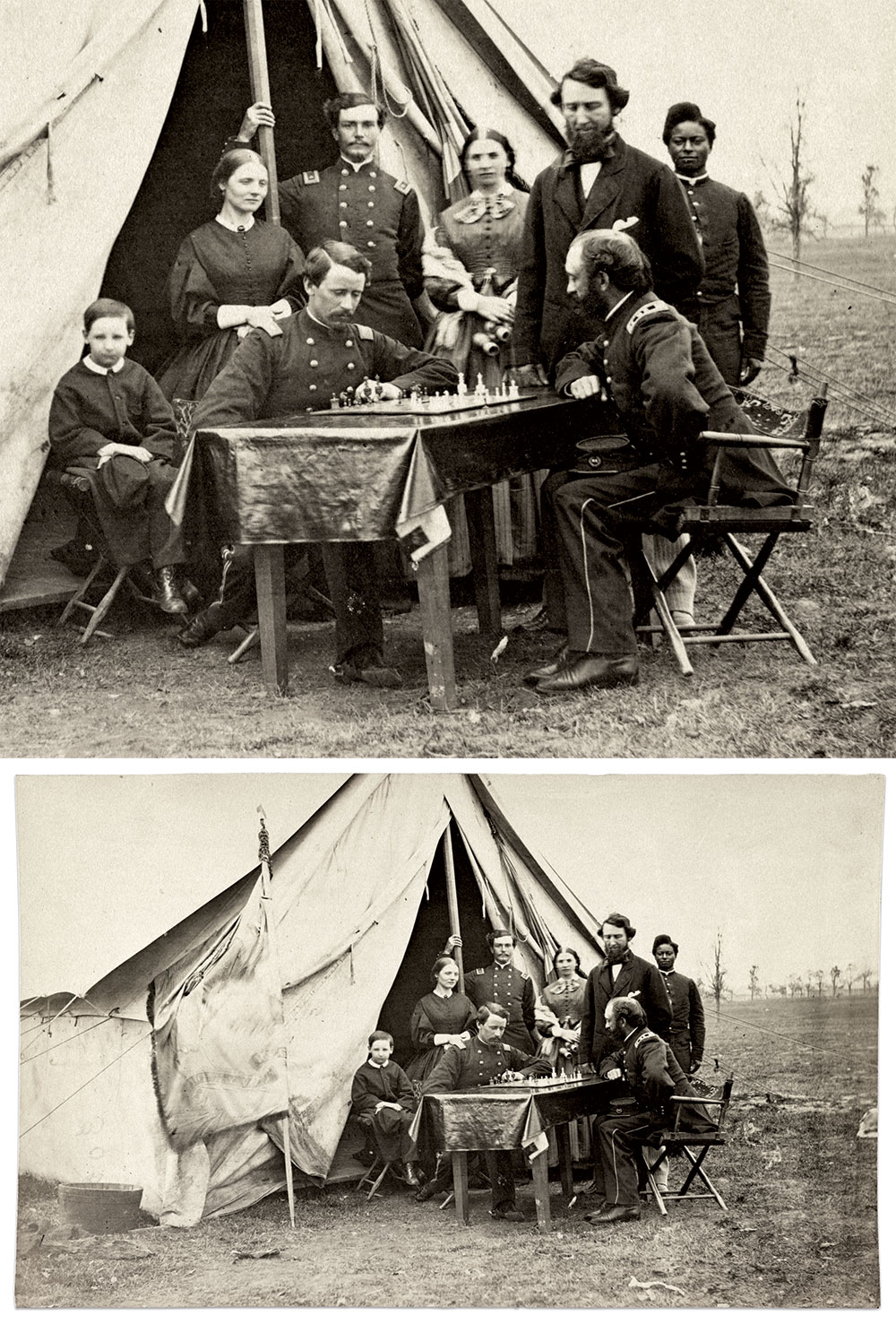

The charismatic commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, had been to the Crimea and witnessed first-hand French innovations to provide comfort to soldiers. McClellan’s observations in Europe, and growing sentiment among his command for waterproof coverings, prompted him to act. He ordered his senior quartermaster officer, Brig. Gen. Stewart Van Vliet, to procure 5,000 Poncho Tents invented by Horace H. Day, a prosperous manufacturer and owner of the India Rubber Company. These items would be distributed to cavalry troopers.

Day set up a prototype near McClellan’s headquarters. It consisted of three waterproof ponchos; two poles segmented in three joints, 20 feet of cord, six pins to secure the tent, two slides to adjust the tension, and bags. The dimensions of the tent measured 71 by 60 inches.

Poncho tents had its pros. The waterproofing technology had advanced since unsuccessful pre-war attempts. Relatively inexpensive and enabling soldiers to carry them, they reduced the size of cumbersome and expensive baggage trains supporting the army.

Meigs appreciated the advantages. Yet, he was also irritated by McClellan’s circumvention of procedures in making the request. Further complicating matters, Meigs’ superior, Secretary of War Simon Cameron, authorized the procurement of waterproof blankets on Nov. 1, 1861.

Meigs did not want to countermand the popular McClellan or disobey Cameron. Consequently, Meigs gave limited approval for the contract with Day.

On Nov. 29, 1861, Meigs wrote to his deputy quartermaster, Lt. Col. George H. Crosman, stationed at the Philadelphia Clothing Depot:

Lt. Col. Geo. H. Crosman

D.Q.M.G. Philadelphia, Pa.

Sir: Your letter in reference to the waterproof covering, or blanket, was duly received. I held it for advisement with the General in Chief. No officers can be spared for a board to investigate the subject, and the India rubber and gutta percha controversy alone has puzzled and employed lawyers and scientific men for years past and is still undecided.

The decision is that some of the gutta percha, some of the India rubber, and some of the painted cloths shall be procured. There are probably 50,000 India rubber blankets now in use by the troops, furnished by the states [primarily NY], and giving great satisfaction to those who use them. About 20,000 painted ponchos, with buttons and buttonholes to make tents abri [sic] have been ordered and are being delivered. These are made by Mr. Day, and were ordered by Gen. Van Vliet under authority from this office.

The India rubber blanket should not be allowed to exceed 2-1/2 lbs. in weight. This fixes its size. Grummet [sic] holes with thimbles of brass should be arranged around the edge at not more than 14 inches interval, and in all to be made hereafter a slit in the middle, lengthwise of the blanket, should be made, with a flap like a pocket flap so as to close the opening completely when used as a blanket and not as a poncho. This flap should be secured to the blanket on three edges. The blankets thus prepared can be used as ponchos, blankets, or shelters and when converted into tents. With these general directions I leave the carrying out of the matter to your discretion. For the present a total supply of not over 100,000 should be ordered. None should be taken without the grummet holes, and none unless the prices are made reasonable. I would not pay a higher price for gutta percha than for vulcanized rubber. If the material cannot be made to compete in price it should not be used. I have seen no satisfactory evidence that it is better than equally well-prepared India rubber.

M.C. Meigs

Qr.Mr.Gen.

Meanwhile, Meigs fielded a request from New York’s governor, Edwin D. Morgan, to supply Empire State troops with vulcanized India rubber blankets. Meigs replied on December 4, explaining that Crosman had been authorized to purchase several kinds of waterproof blankets. Meigs also recommended that they be supplied through regular requisition channels to avoid competition and achieve uniformity. Meigs added, “I have directed those manufactured for the United States, to be made with a straight slit and flap so as to be used as a poncho, and with thimble or grommet holes at 14 inch intervals around the edges so they can be laced together as shelters in place of tents, in bivouac.”

Technology and innovation blurred the lines between poncho and blanket.

Meeting supply chain challenges

Meigs’ instructions provided the basis for the introduction of up to 150,000 ponchos and waterproof blankets in 1862. He followed up with his deputies, informing them that purchase contracts should be handled in the same way as clothing, and in consultation with his office.

Meigs also warned, “I have found the India-rubber interest, one of the most difficult to deal with. The agents of different processes so abuse and decry all rivals that it is impossible to arrive at the truth—but it is certain that those who are rejected here for bad quality of material or for high charges, will make desperate efforts to sell their wares to Western quarter masters, governors and colonels.”

Meigs calculated that 20,000 of Day’s poncho tents supplemented by waterproof blankets, customized with slits and flaps to make them serviceable as ponchos, would satisfy McClellan’s initial request—and be a less expensive alternative to the talma, which was on its way out.

McClellan tossed a wrench into Meigs’ plans. On Jan. 17, 1862, Meigs received a letter from Van Vliet informing him that McClellan wanted to include the issue of ponchos to infantry in addition to cavalry.

This abrupt change in plans exasperated Meigs, who paused to consider needs for both branches of the military. He halted procurement of Day’s poncho tents after 2,000 of the 5,000 under contract were delivered.

Meigs modifies his plans

Meigs reconsidered the approach, and decided that soldiers needed two items of shelter, one above them and another below them. The rubber poncho blanket insulated the soldier from the ground in camp or kept him dry on wet marches and field operations. A linen or canvas shelter tent protected him from the elements.

Both items were fitted with 16 grommets to insure maximum coverage in all weather. The poncho blanket had two extra grommets for ties to secure it around the soldier’s neck.

By mid-war, according to specifications provided to contractors by the New York Depot, the India Rubber Tent Poncho measured 45 by 72 inches of vulcanized material and weighed two-and-a-half to three pounds. The dimensions differ from those listed by Crosman in an unpublished 1865 manual focused on the Philadelphia Depot: 60 by 71 inches. In fact, specifications varied by depot through the rest of the war.

India rubber blankets received another boost in Aril 1863 after Meigs instructed his deputies to contract for them instead of painted cloth blankets. Consequently, purchases of painted ponchos and blankets declined beginning in 1864.

Gutta percha and India rubber remained in use through the rest of the war, even as the performance of these materials remained in question. In Crosman’s 1865 unpublished manual, he described both finishes as acceptable. Other depots may have favored one finish over the other, or ordered what was available when more were required.

Crosman’s manual did differentiate waterproof blankets from ponchos. However, it had no practical effect as enlisted soldiers sought what they wanted, regardless of what they were issued.

The cavalry version: “To be made of a good, strong material, coated with gutta-percha or india [sic] rubber, vulcanized. The ponchos to be 71 inches long and 60 inches broad. The grommets to be placed equidistant, not exceeding 14 inches. They must both be bound all around, or hemmed. The slit or collar in the centre of the poncho, must be strongly sewed with 2 rows of stitching, and must be 3 inches wide, and 16 inches long, when completed.”

The infantry version: “46 inches wide by 71 inches long, without the slit for the head; but having the grommet arrangement the same as for the poncho. A string of stout webbing, 12 inches long, to tie them on, with [two] extra grommets for it, instead of [a] slit for poncho. The grommets, in all cases, to be 1 inch from the centre of the grommet to the edge of the blanket on one side and end, and 2 inches from the other side and end. The grommets must be stayed [i.e., reinforced], and be placed equi-distant, so as to match, and be made of brass.”

One can see why infantrymen preferred the larger cavalry version with its convenient slit.

Conclusion

A final reflection on the importance of rubber goods as shelters is found in a report on the operations of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Georgia Campaign, also known as the March to the Sea. Lt. Col. Ephraim M. Joel, Chief Quartermaster of the 17th Corps, wrote to Meigs on April 17, 1865, “Gum blankets and Ponchos have become almost an indispensable part of the Soldier’s outfit, between the two there can be but little choice. In many of the commands the Men make a first rate Shelter Tent from the Gum Blanket” almost to the exclusion of cloth tents.

Meigs’ intentions at the beginning of the war to consolidate items of the soldiers’ load had been moved in that direction by war’s end—by the soldiers themselves.

Quartermaster Department Col. Alexander J. Perry’s 1865 report provides official numbers of ponchos and waterproof blankets purchased from contractors during the Civil War: 1,596,559 ponchos and 1,893,007 waterproof blankets. None were produced in any of the four primary Quartermaster depots of construction and distribution (Philadelphia, New York City, Cincinnati and St. Louis) due to lack of access to patented processes used by the contractors. It is interesting to compare these numbers to those compiled from extant Quartermaster Department contract records in Treasury Department records, which list 1,158,733 ponchos and 1,753,401 waterproof blankets. The Union India Rubber Company of New York City supplied the largest number of items, with 25 contracts for 525,000 ponchos and 500,000 rubber blankets.

The Civil War saw many innovations in the arms, uniforms and equipment of the soldiers. Doubtless these fighting men considered rubberized, waterproof items a significant improvement to their individual comfort.

Frederick C. Gaede is an occasional contributor to MI. He has written articles for the journal Military Collector & Historian and other publications.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.