By Kurt Luther

Photo sleuthing is not always a blank slate. While many Civil War photos come to us unidentified, others bring names and stories with varying amounts of evidence to back them up. A skeptical researcher may discover that proposed identities, even from reliable sources such as professional archives and scholarly publications, can be mistaken, yet the subsequent investigation reveals that the truth is more exciting than the myth. In this column, I will show how a misidentification can propagate for more than a century. Returning to primary sources can not only help us correct the historical record, but also unlock new discoveries.

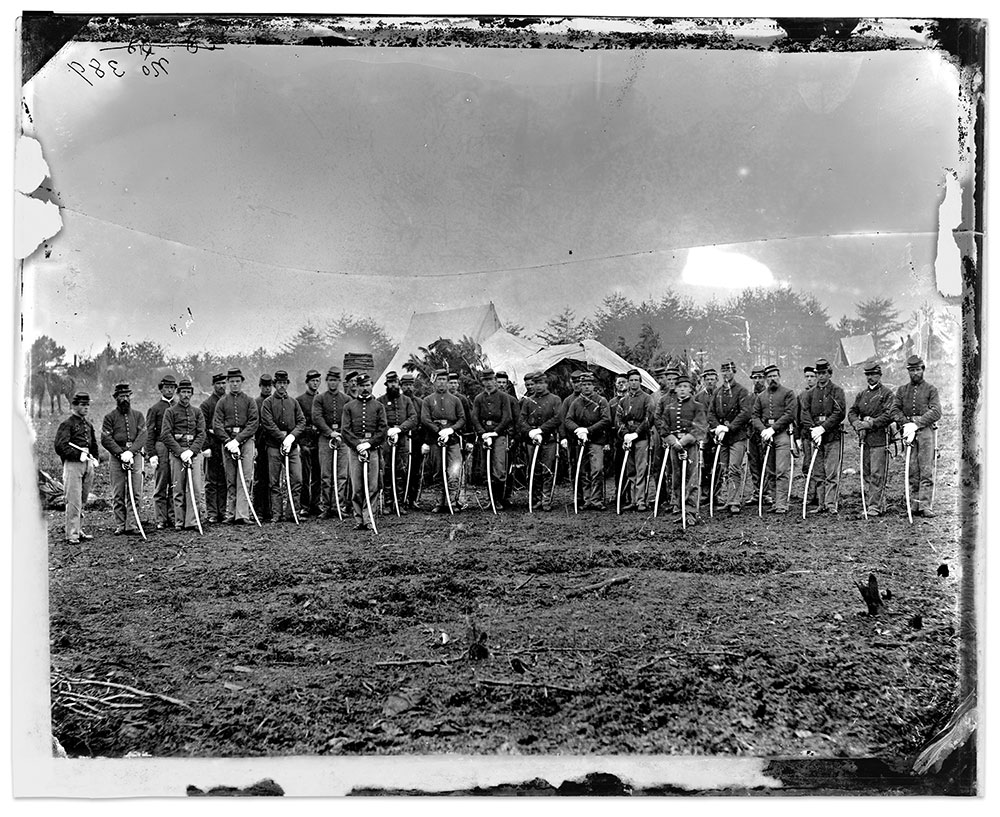

I recently came across a wonderful group portrait of Union cavalrymen in camp that veteran photo sleuth Garry Adelman had posted on his popular Civil War page on Facebook. Adelman frequently shares Civil War documentary photos with his readers, along with colorful descriptions demonstrating his eye for detail. He noted the “dreary-looking scene” and the serious appearance of the soldiers “without a single smirk or smile.”

The photo’s source, linked by Adelman, is a glass negative in the Library of Congress collections, captioned, “Brandy Station, Va. Troopers of Co. D, 3d Pennsylvania Cavalry (2d Division, Cavalry Corps).” The 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry formed in 1861, and participated in most of the major battles of the Eastern Theater, including Gettysburg, where they clashed with J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry on the battle’s third day. The Library of Congress attributes the photo to Timothy O’Sullivan and dates it to March 1864. None of the troopers are identified.

Group portraits in the field always intrigue me because they present an opportunity to bring together two Civil War subcultures—portrait enthusiasts and documentary photo enthusiasts—that overlap less often than one might expect. I found this photo particularly appealing because so much information was seemingly readily available. The specific military unit, approximate date and location, combined with a glass negative scanned and digitized at high resolution, could allow me to identify many of the photo’s individual subjects. Often, these field photos offer the only extant identifiable views of some soldiers, especially in the lower ranks. As the Library of Congress’s caption did not name any of the men pictured, I jumped at the opportunity.

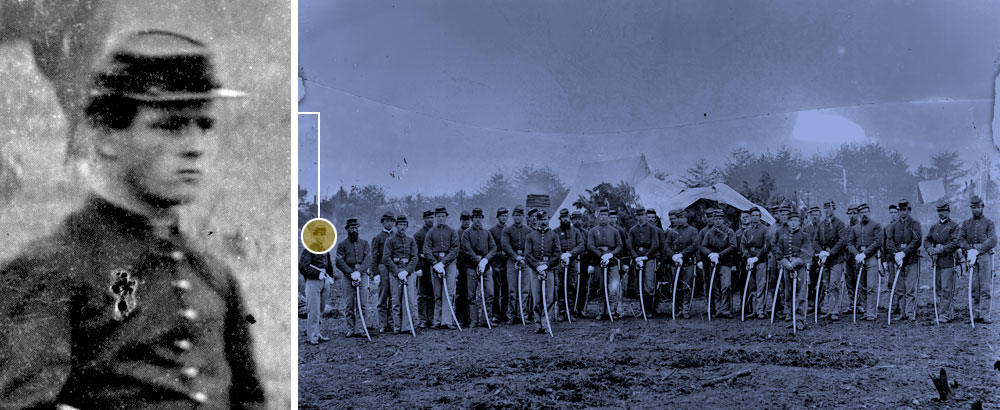

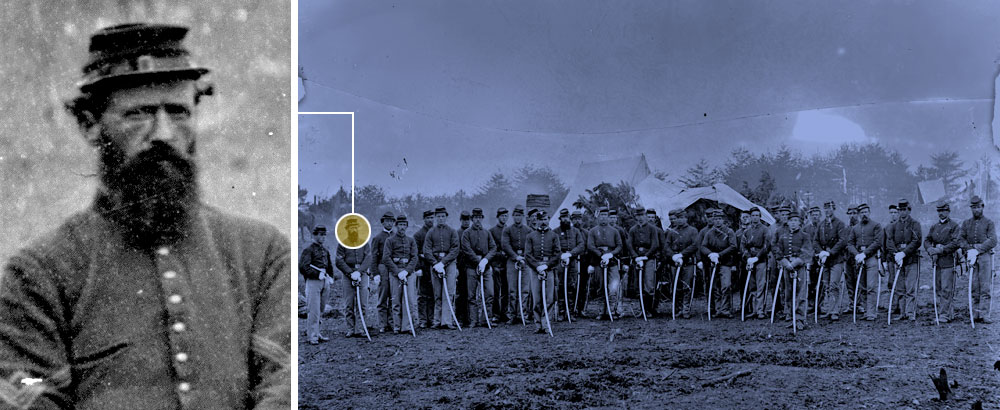

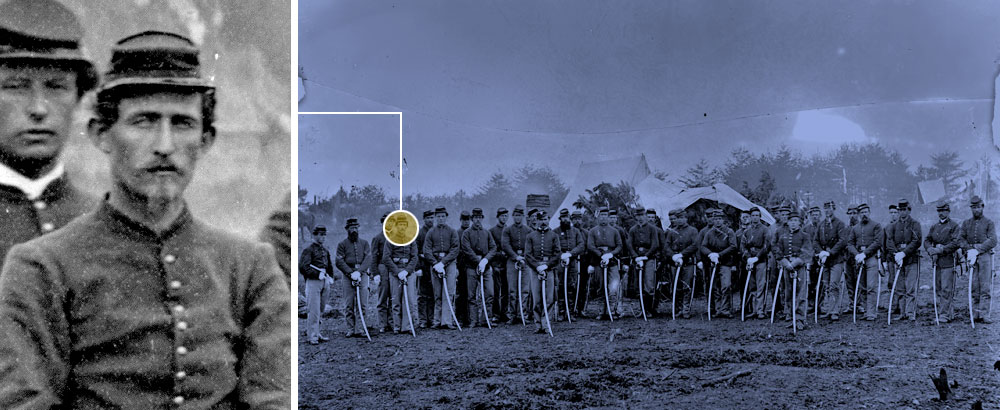

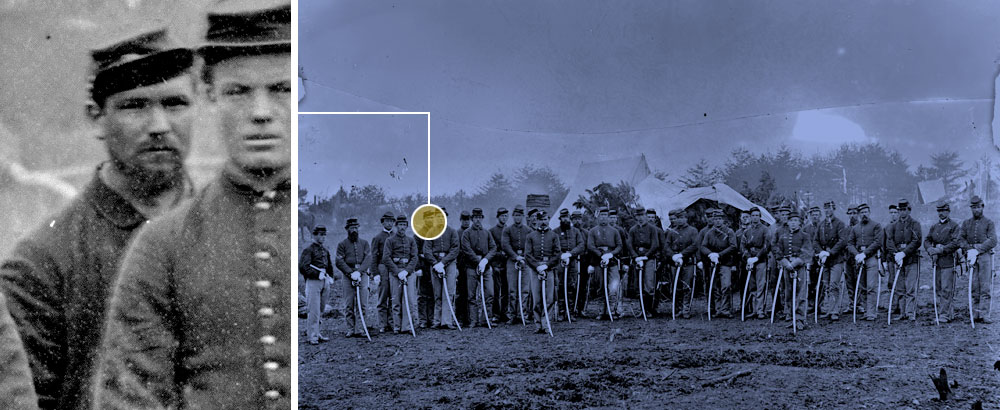

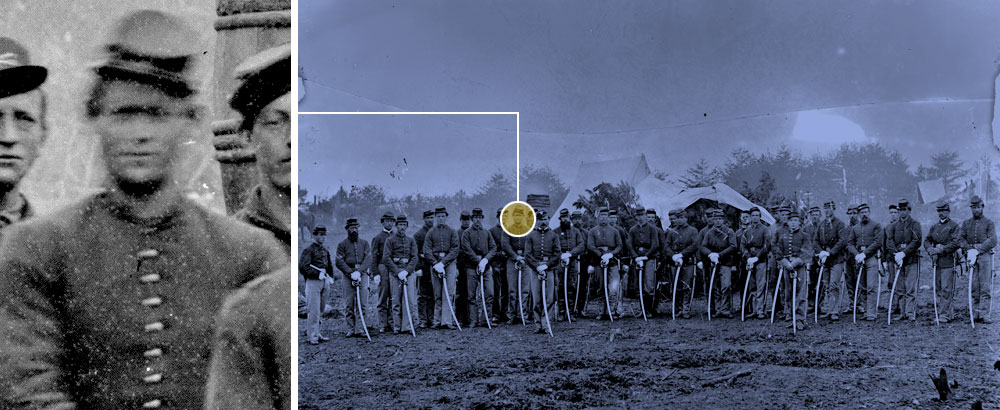

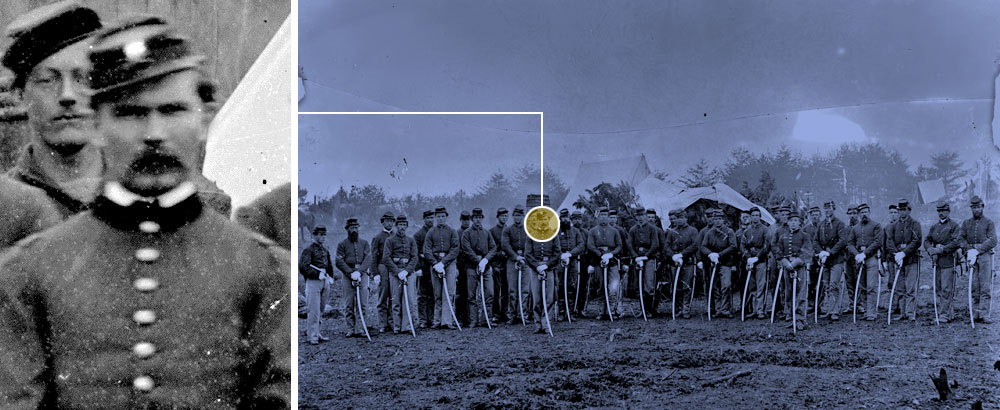

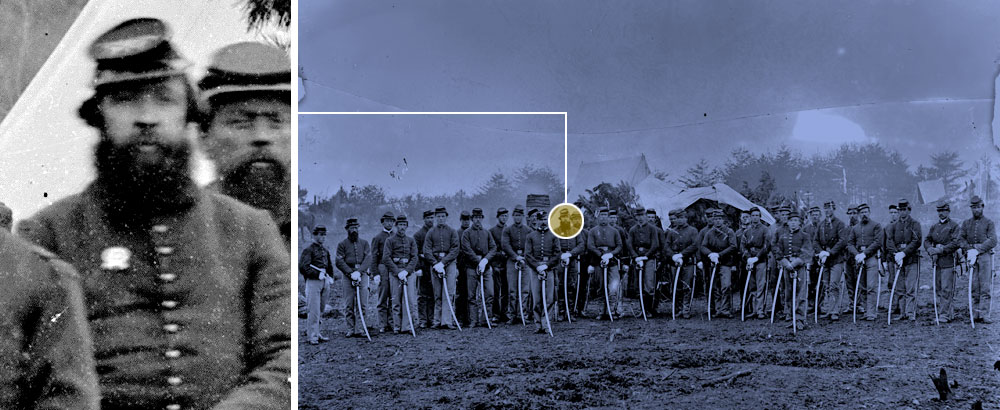

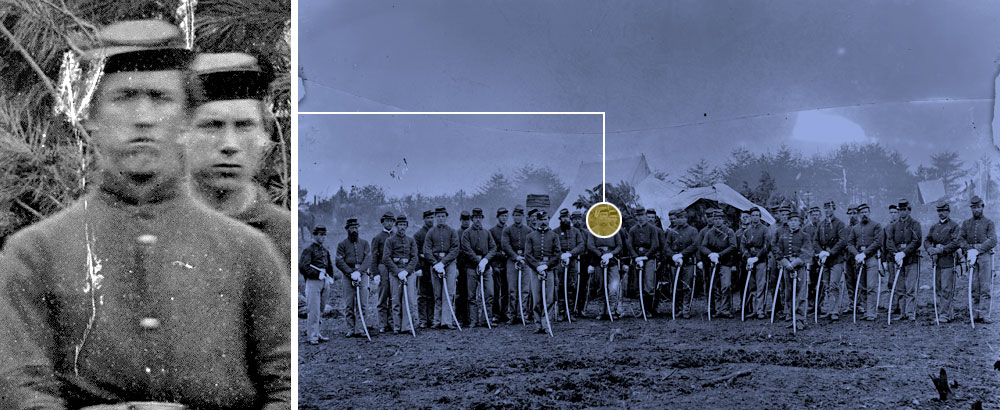

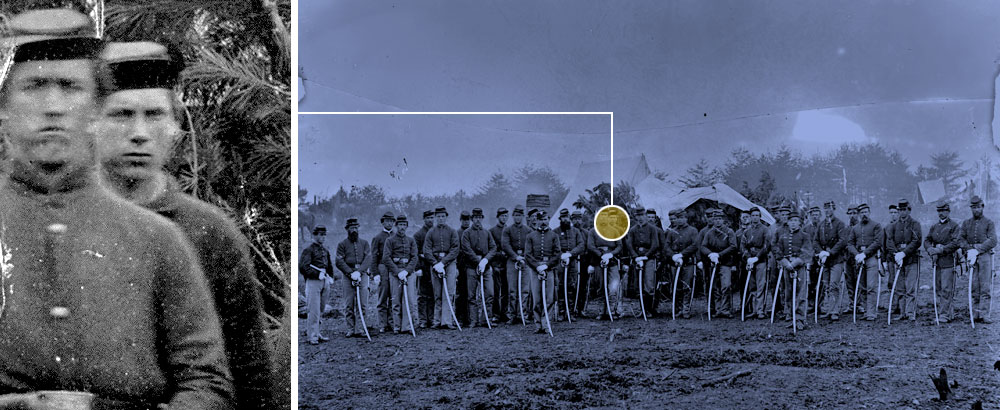

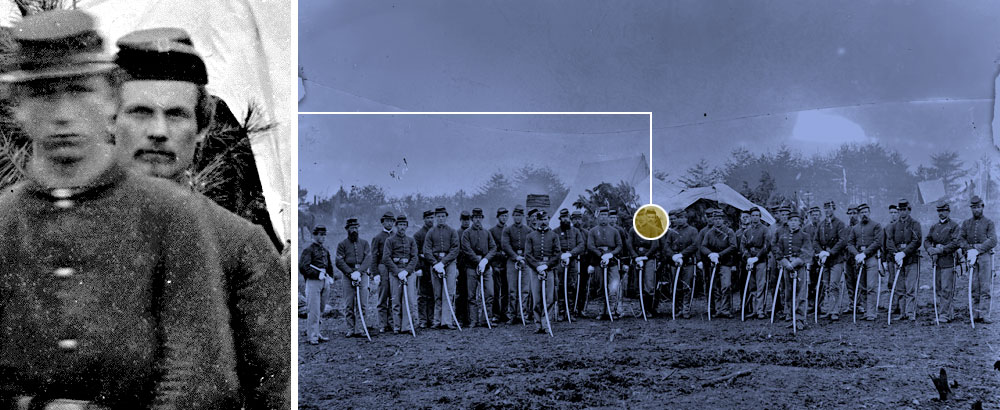

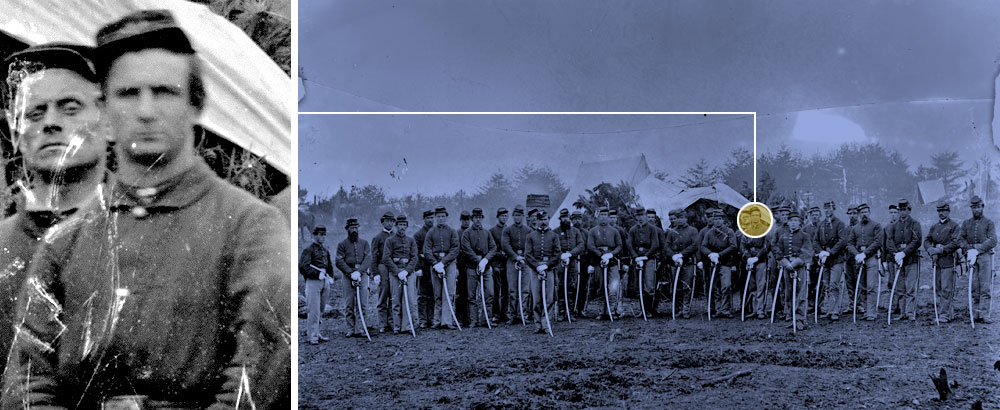

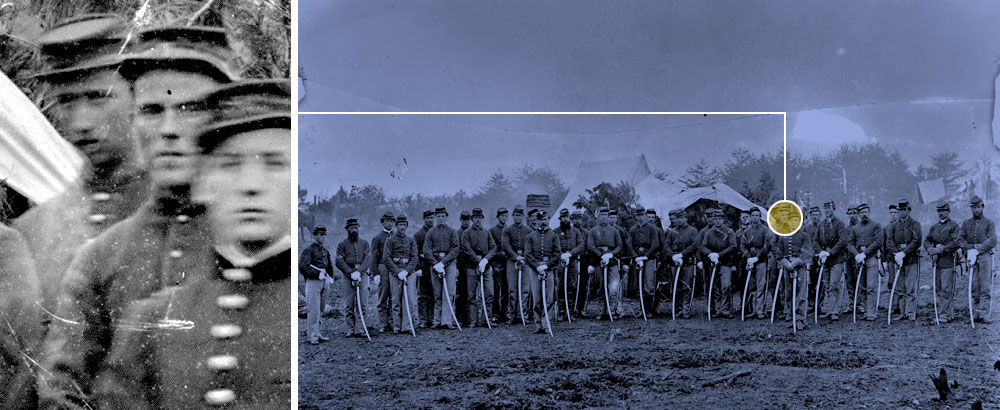

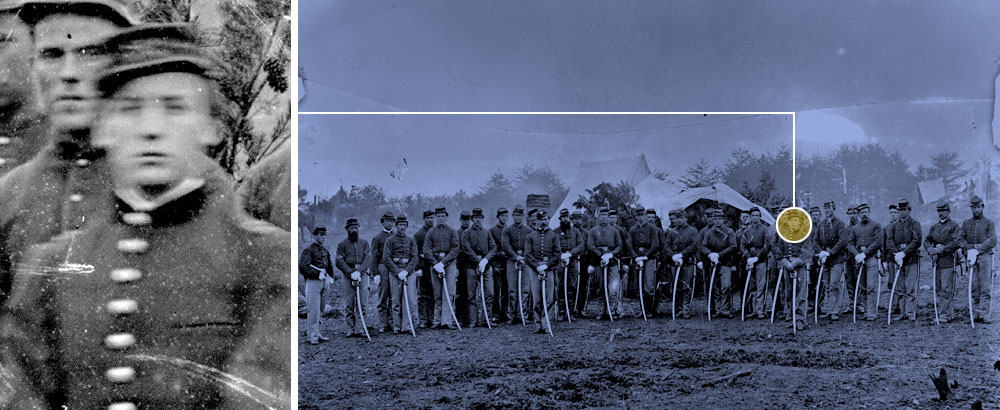

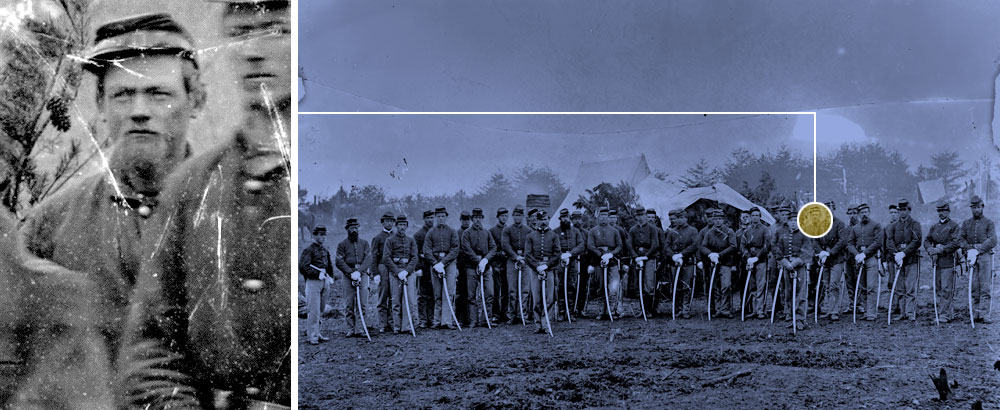

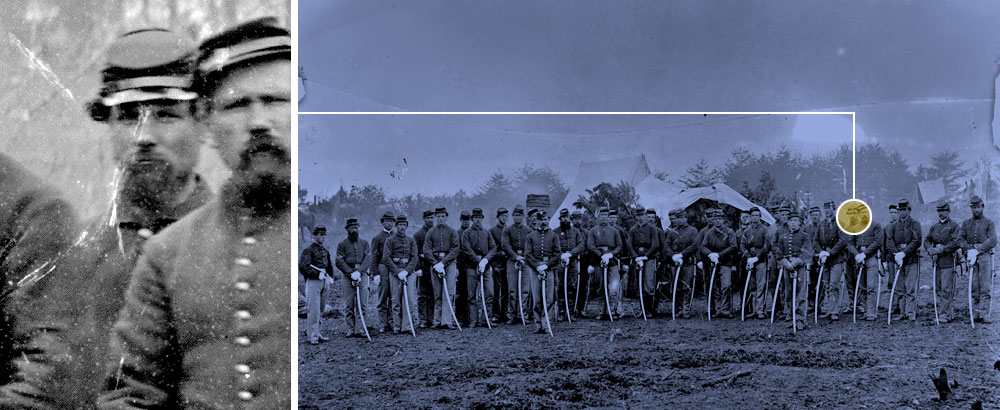

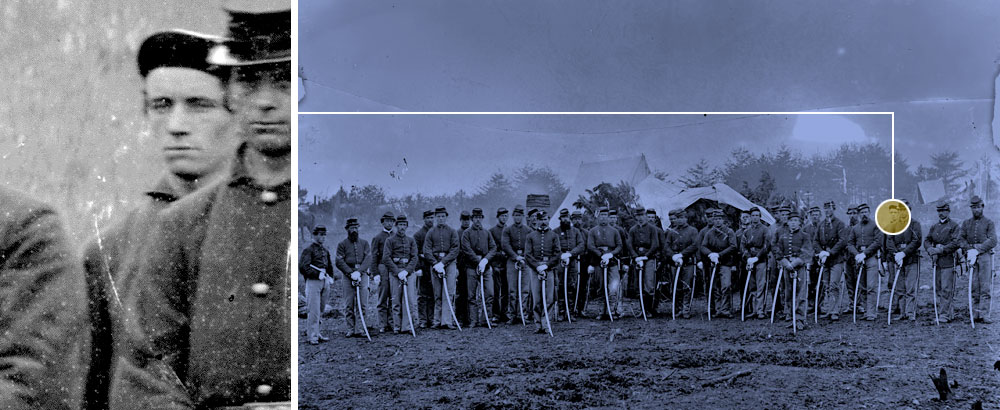

I downloaded the highest-resolution scan available from the Library of Congress and took a closer look. The photo shows an outdoor camp setting with trees, horses, tents and a carpeted camp chair in the background. A barrel chimney beside a tent or hut suggests some permanence to the campsite. There are 35 men pictured. They wear forage caps and a mix of federal shell jackets with trimmed collars and sack coats. Most wear brogans, but a couple have on knee-high riding boots. All but a few wear white gloves or gauntlets. The men stand at parade rest, their unsheathed cavalry sabers pointed towards their left feet. The soldiers’ rank insignia reveal a mix of mostly non-commissioned officers and privates, including a bugler and a first sergeant on the extreme left. Two line officers wearing shoulder straps of indeterminate rank stand in front.

Company C, 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, April 1864

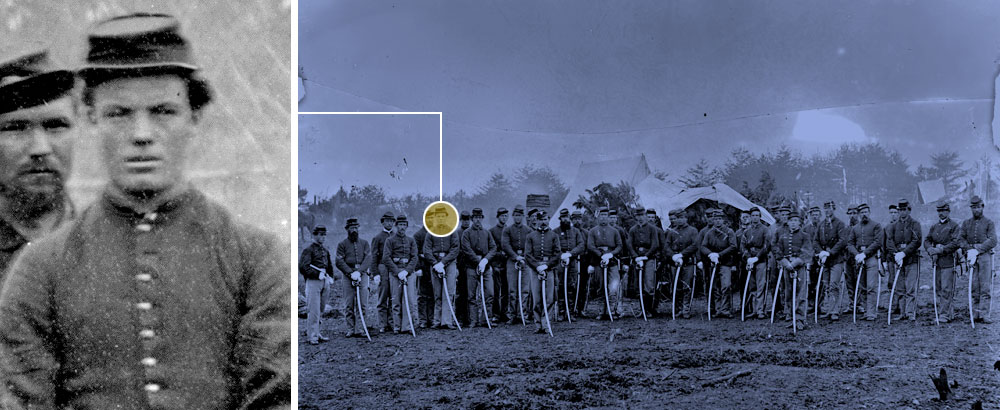

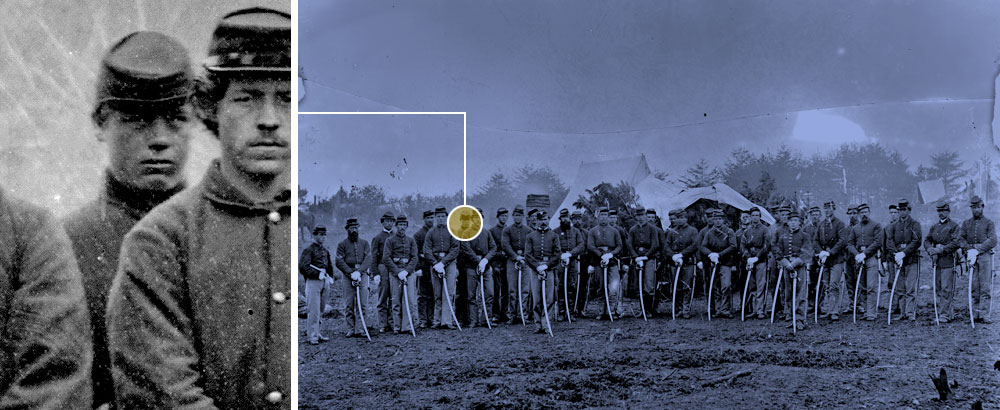

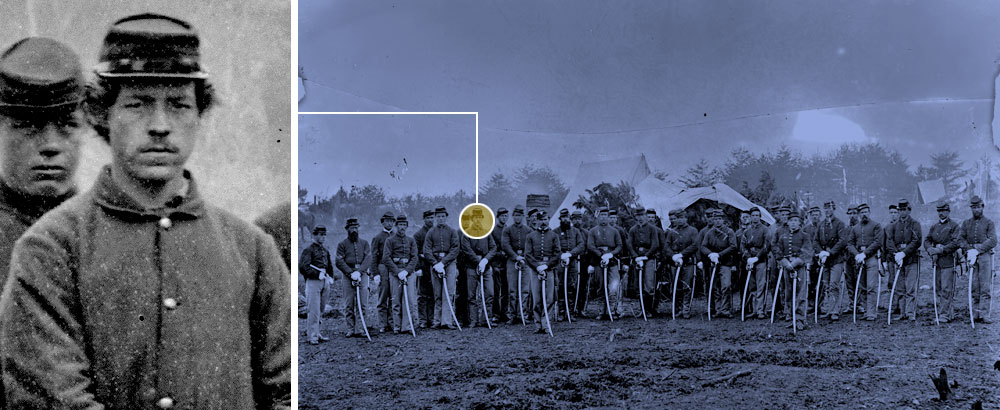

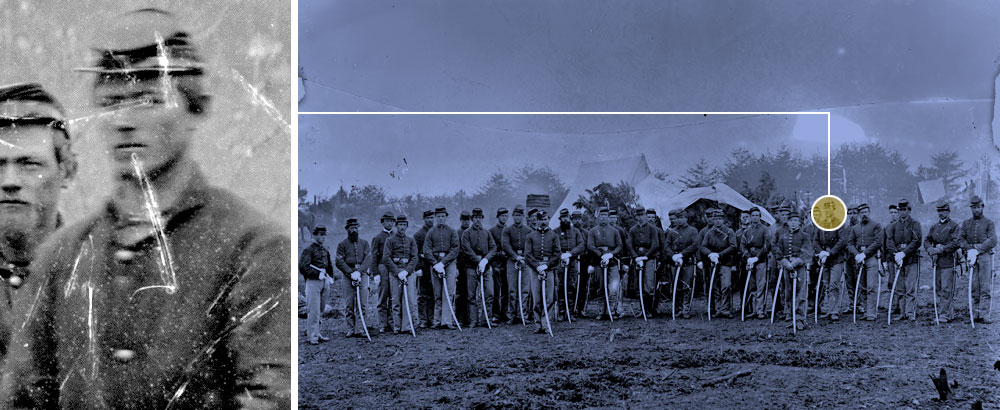

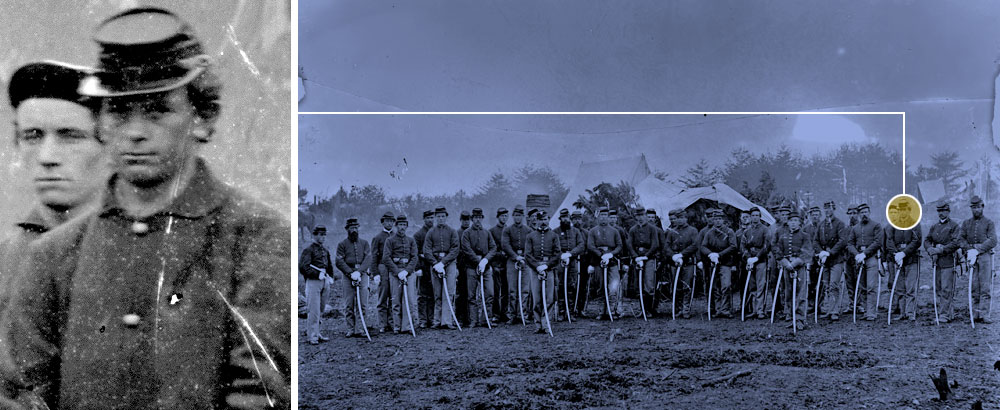

Zooming in, I noted that the troopers’ uniforms are largely unadorned. I counted a single corps or identification badge and a handful of hat brass, mostly cavalry insignia. Only one of the 35 soldiers has a visible company letter on his cap. To my surprise, I saw that it was clearly a “C,” not the “D” that I expected from the caption’s “Co. D.” This tiny discrepancy set me on a path to discover the identities of every man pictured in the photo.

I found myself in a similar situation as in a prior MI column (Spring 2020), when I corrected a series of misidentified Veteran Reserve Corps group portraits in the Library of Congress collections. Then, as now, contradictory company letters on the hat brass raised doubts about the caption’s accuracy. If the company is wrong, what else might be wrong? Is this the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry? How about the purported date, location and photographer?

In that earlier investigation, I found that consulting period regimental histories proved invaluable to helping me solve the mystery. In fact, one such book contained an identical view with an accurate caption that had been distorted over time. Taking a page from that book, I downloaded from Google Books a free digitized copy of History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry (1905), written by a group of veterans of the unit led by Capt. William Brooke Rawle (He flipped his middle and last names after the war). The well-illustrated book includes individual portraits of most of the regiment’s commissioned officers, from the original commander, William Averell, down through second lieutenants, but non-commissioned officers and enlisted men are notably absent.

The book also contains several group portraits, including two wartime views of men of the regiment, both dated April 15, 1864. The first is a mixed group of officers. The second photo, I recognized with joy, is a print of the Library of Congress negative, captioned, “Company C, Third Pennsylvania Cavalry.”

This caption not only established that the photo does indeed depict the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. It also supported my suspicion, sparked by the conflicting hat brass, that the photo actually shows Company C, not D. However, I wanted to be sure. Next, I wanted to identify at least a few of the pictured soldiers as members of Company C.

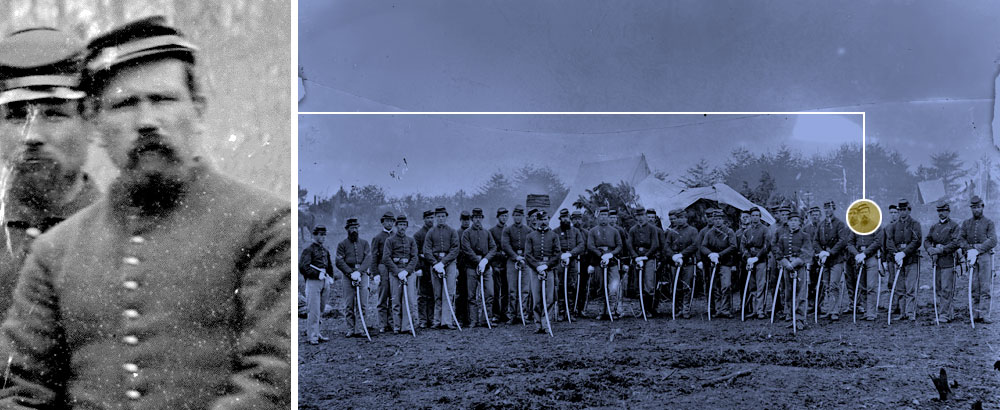

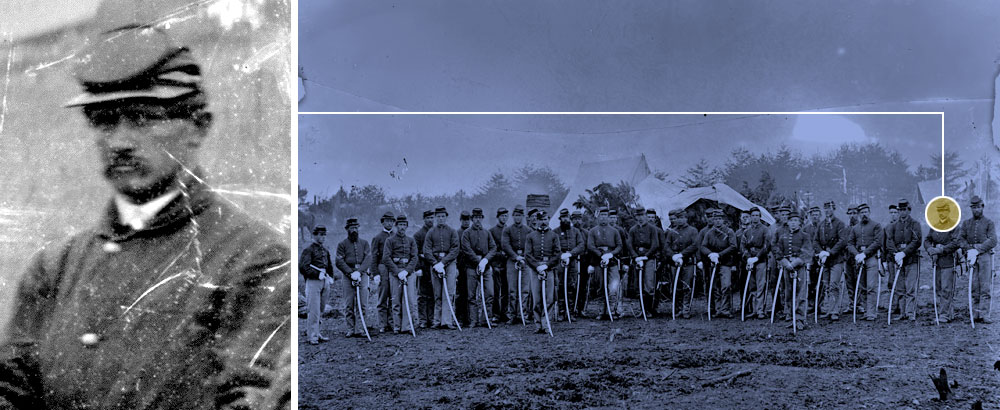

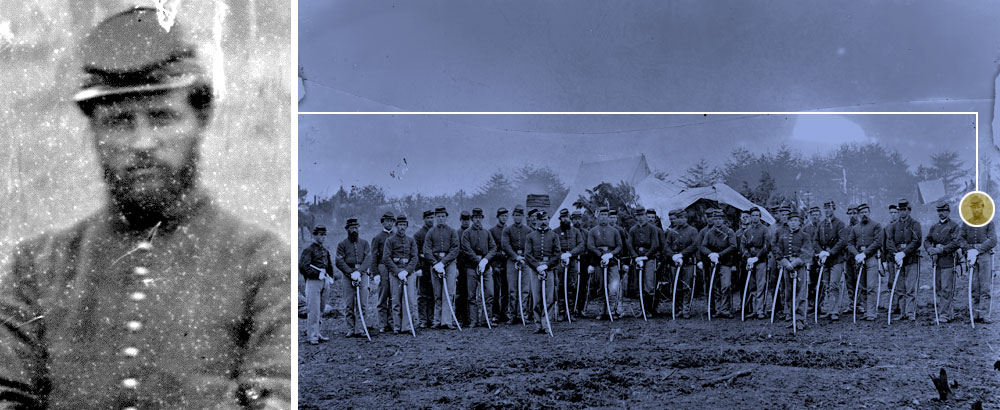

As I turned the digital page in the regimental history, my excitement doubled. The book’s authors had included a key that identified every soldier and his position in the photo. According to the key, the two officers are Miles Carter, left, and William Rawle Brooke, right, both lieutenants in Company C. As Brooke was the regimental history’s lead author, this identification is about as airtight as it gets, though individual portraits of these officers published elsewhere in the book offer further confirmation.

The key reveals that most of the company’s noncommissioned officers stand on either side of the front row, including the aforementioned first sergeant (now identified as John Brandon) and bugler (Charles Key) on the far left, and Quartermaster Sgt. Jacob Hartenstein on the far right. The men standing in the middle of the front row and most of the back row are privates.

The regimental history offers another gem, a rare example of soldiers writing about having a specific wartime photo made that survives today: “The regiment had become so much reduced in numbers that Major [O. O. G.] Robinson and Captain [William] Baughman, with a detail of men, were sent to the North on recruiting service. Before leaving, on April 15 [1864], the army photographer, Gardner, took a picture of some of the officers then present for duty with the regiment, and also one of Company C, copies of which we are fortunate in being able to have reproduced for this work.”

This text reiterates the caption’s date of April 15, 1864, at least a couple of weeks later than the Library of Congress’s March 1864 date. Additional evidence from the regimental history supports the April 15 date. The key for the group portrait of mixed officers identifies Robinson and Baughman seated together in the first row, supported by facial comparisons to their individual portraits elsewhere in the book and Robinson’s field-grade uniform coat. Clearly, they had not yet departed for recruiting duty. Additionally, the key identifies Joel Rammel in the same photo wearing a chaplain’s characteristic dark frock coat. Rammel had been promoted to chaplain from sergeant on March 20, so the photo could not have been taken earlier.

The claim about Gardner is more difficult to verify. Timothy O’Sullivan worked for Alexander Gardner, so the text may refer to Gardner himself or his studio more generally.

Where did the misidentification of “Company D” originate? The earliest instance I found was in Miller’s Photographic History of the Civil War, Volume 4: The Cavalry. It includes a two-page spread of the Company C photo, minus the unlucky Bugler Key, who has been cropped out. The caption reads, “Some of Pleasonton’s Men at Gettysburg” on the first page, and “Company D Third Pennsylvania Cavalry” on the second. Published in 1911, only six years after the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry’s regimental history, Miller’s book either created or furthered the “Company D” error that would propagate over more than a century to almost every modern-day source, including the Library of Congress official item description, Milhollen and Mugridge’s 1961 reference catalog Civil War Photographs, upon which the caption was based, and popular websites like Wikipedia and PaCivilWar.com. In a 2021 HistoryNet.com article, Brooke’s biographer, J. Gregory Acken, points out Brooke in the Company C photo. But since he later served as captain of Company D, his presence per se does not disambiguate the group.

Researching this photo allowed me to correct some widespread misinformation about the identity of the military unit and the date of the photo. But perhaps more importantly, it illuminated the names and stories behind the faces of 35 Civil War soldiers, many of them noncommissioned officers and enlisted men for whom no other reference image is extant. Indeed, my initial search for reference photos of 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry members on Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) and the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) turned up only a handful of results, mostly high-ranking officers.

While the regimental history once identified these soldiers on the printed page, we can finally connect them to the original negative, the “witness glass” handled by Timothy O’Sullivan or Alexander Gardner at Brandy Station on April 15, 1864. The high-resolution scan of this negative, combined with the comprehensive identification of its subjects, provides a glimpse of rare and rich detail into the life of the Civil War cavalryman.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.