By Dominick A. Serrano

Collecting Confederate images has never been easy. The ambrotypes and cartes de visite have always been more costly and elusive than their Northern counterparts, and finding fine examples can be a wonderful yet daunting experience. Although soldiers armed with Bowie knives and muskets are always in demand, there is one photographer’s output that remains preeminent for image collectors, that of Charles Ricard Rees.

The seven decades that Rees worked as a photographer are all but forgotten except by a handful of Civil War collectors. Unlike many of the earliest pioneers of the art, he left no journals or reminiscences and is barely mentioned in the many books written about early photography. His story is not just a reflection of his life, but more an account of the advent of photography in America and especially of his adopted home, Richmond, Va., during the war.

In 2012, I penned an article, “Southern Exposure, The Life and Times of C.R. Rees.” Since then, new information has surfaced—and perplexing questions about his career in the closing months of the conflict.

Rees was born on Jan. 26, 1825, in the Pennsylvania Dutch community of Allentown to German immigrants. Like many children in that area, he grew up speaking German and some English, but proved proficient in both languages. His career as a daguerreotypist started around 1843 in Cincinnati, where he probably apprenticed in one of the city’s studios.

Photography was a groundbreaking phenomenon in that decade with many similarities to today’s mania for cutting-edge technology. It’s not surprising that the new process drew young men from various backgrounds into the field. Rees moved to several large cities in the early years learning new techniques at every stop and acquiring friends and enemies along the way, characteristics he displayed throughout his life.

Early 1850s: Fighting for recognition in New York City

By 1852, the new art form had become immensely popular and inexpensive. New York City boasted more than 80 studios mostly clustered on lower Broadway and the Bowery in Manhattan. Fortunes were made and lost with some of the most famous names in photography, centered in a few short blocks of each other. A competitive atmosphere was paramount, with price wars and slandering one’s competition a natural occurrence.

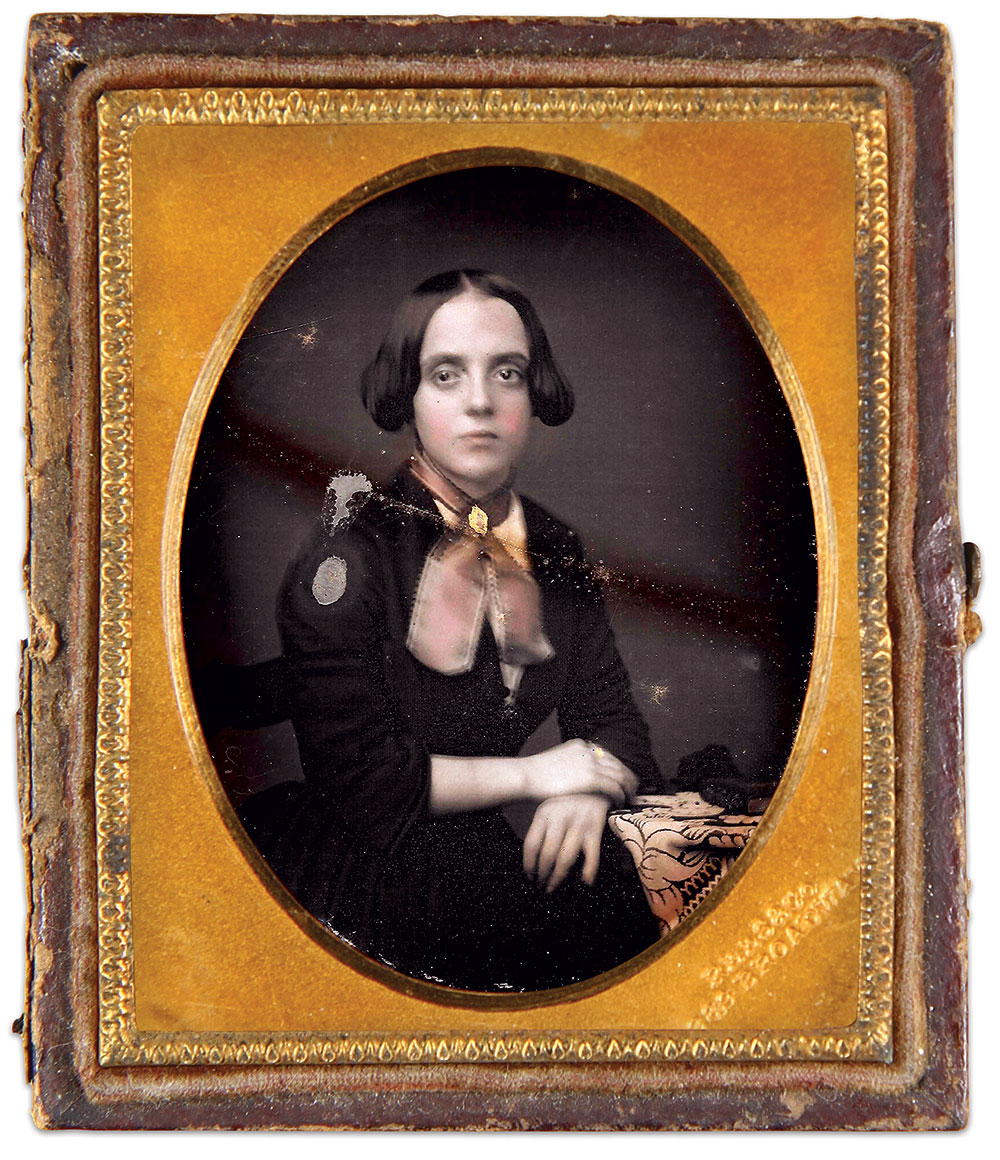

Rees, a 27-year-old bachelor, entered the city’s photography maelstrom as an accomplished artist ready to fight for recognition. He formed an association with the gallery of Silas A. Holmes at 289 Broadway, operating it under the name Rees & Co. Not enjoying the name recognition of Brady, Gurney or Meade, who operated elegant and popular studios nearby, Rees promoted his gallery with scathing advertisements, bold claims, and lower prices to establish his reputation.

One ad claimed, “The Two Shilling Daguerreotype System originated by Rees & Co., with their new German process and power plate machine to take 300 pictures daily, proves the greatest feature in art of all modern improvements—it upsets the old fogies in the profession and the small potato clique who attempt to rival and imitate their work. Some nude professors of model artist notoriety, who claim years of famous experience in the art, wake up amazed that a poor German gentleman with enterprise and invention, should have introduced a system of picture-making which no rival can imitate, and with which it is leading him on to fame and fortune, notwithstanding the fog and fogyism and inventions of the enemy.”

Concurrent with newspaper ads, advertising broadsides and cheaply printed pamphlets were used by 19th century businesses to extol products and services. New York City photography studios deployed these paper missives extensively, passing them out to potential customers on the busy streets of Manhattan.

Rees produced a most peculiar and fascinating pamphlet filled with poetry, incredible claims and hyperbole. He depicted himself as a persecuted German refugee who had been imprisoned for several years in Europe by “Tyrannius moneyed powers of the Aristocracy.” He invented fanciful names for his employees: Professor Marat of the coloring department, Doctor Dutton Van Skiok and Senor Lennorda, developing department, and Sir John Clark, gilder. Notorious squirmers, photos of children under 10 years of age were charged not less than 50 cents; babies taken alone one dollar, with their mothers 50 cents. A typical ninth plate cost only 25 cents, and with a common case, 62 cents. Pricing went up accordingly, with a full plate costing 6 to 10 dollars.

Meanwhile, Rees acrimoniously ended his partnership with Holmes. He briefly moved one block up Broadway to the establishment of McClave and Merritt, again operating under his name. In two years, he had produced thousands of daguerreotypes of the highest quality. But he ultimately failed to gain recognition and financial success. By the fall of 1854, he left New York City to seek his fortunes elsewhere.

Rising star in antebellum Richmond

Daguerreotypists were a transient lot, always seeking better markets to ply their trade. Rees worked in various cities throughout the country from late 1854 until 1857, when he settled in Richmond. His newlywed wife, Minerva Jane Beitler, accompanied him. Ten years Rees’ junior, they likely met in her hometown of Cincinnati.

Rees went to work in the studio of Edward M. Tyler and Company. Tyler, with Rees probably as a copartner, operated rooms at the old Pratt Daguerreotype gallery at 139 Main Street in downtown Richmond.

Rees promptly became embroiled in a malicious verbal war with other photographers in the city. He accused one photographer of “depriving a poor woman of her shawl because she refused to pay for an unsatisfactory picture,” and described other competitors as “bags of gas and foul mouthed imitators” in Tyler’s advertisements.

Ambrotypes had, by this time, replaced daguerreotypes as the preferred method of photography. Taking one’s picture became “as cheap as reticule but as durable as Cheops.” Lower prices and a faster process fueled existing price wars in the art. Prices were driven so dangerously low that a group of New York ambrotypists attempted to organize to secure a “fair standard for their work.”

Rees publicly decried Richmond competitors as “bags of gas and foul mouthed imitators.”

In Richmond, Tyler and Rees’ underselling of the competition led to fights and arguments on the street with a rival photographer that fanned the flames of their advertising. The acrimony finally quieted down, and, by late July 1858, Rees took over the studio from Tyler.

This relative period of calm did not last long. Just past midnight on Oct 1, 1859, the Richmond Fire Brigade responded to a raging fire at Rees’ Gallery of Art. A local newspaper reported, “The firemen worked with energy and stamina, (but) they need a few lessons from the red shirt boys of New York on how to extinguish a fire.” The studio was destroyed, and the planting of an incendiary device suspected. No doubt alcohol and ether used in processing photographs fueled the inferno.

One might believe that his enemies had triumphed. But Rees turned the loss into an advantage when $1,000 of insurance money enabled him to lower his prices from 50 to 25 cents at a bigger and better gallery located a few doors down at 145 Main Street.

War boosts business

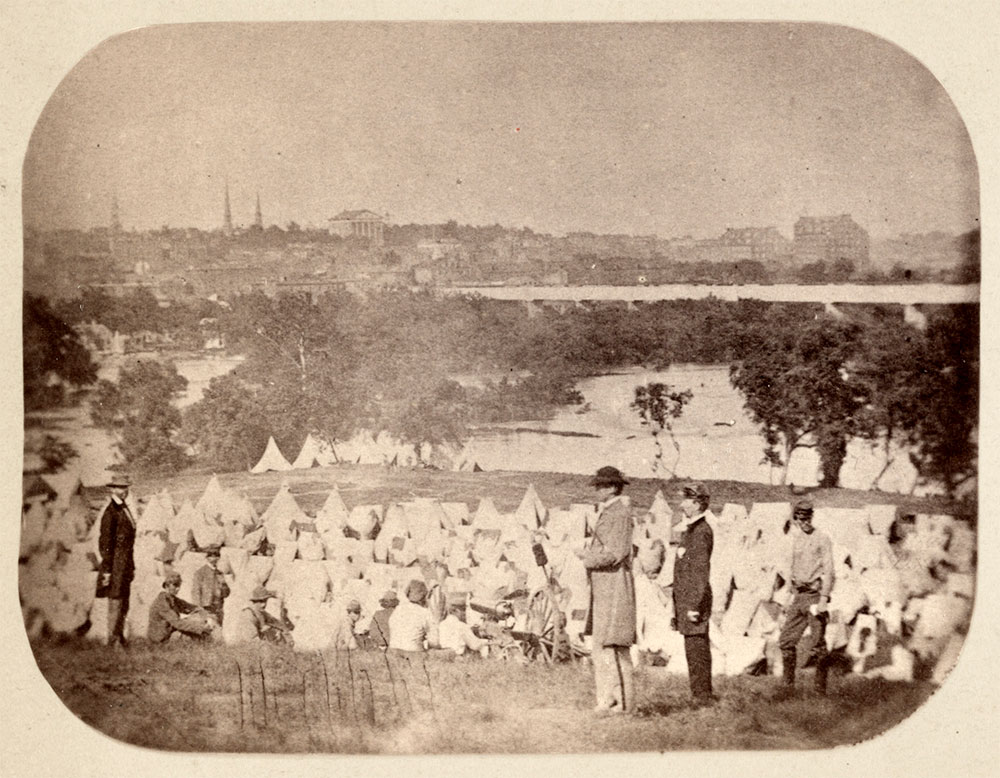

The spring of 1861 saw the formation of a new government in North America, and Richmond as its capital and industrial hub. The population more than doubled to more than 100,000. Politicians, office seekers and soldiers provided plenty of customers for the roughly half-dozen galleries located around the Capitol.

A short walk on Main Street provided a wealth of choices: Vannerson and Jones, G.W. Minnis, Powers and Duke, Hood, P.E. Gibbs. All profited from the influx of patrons.

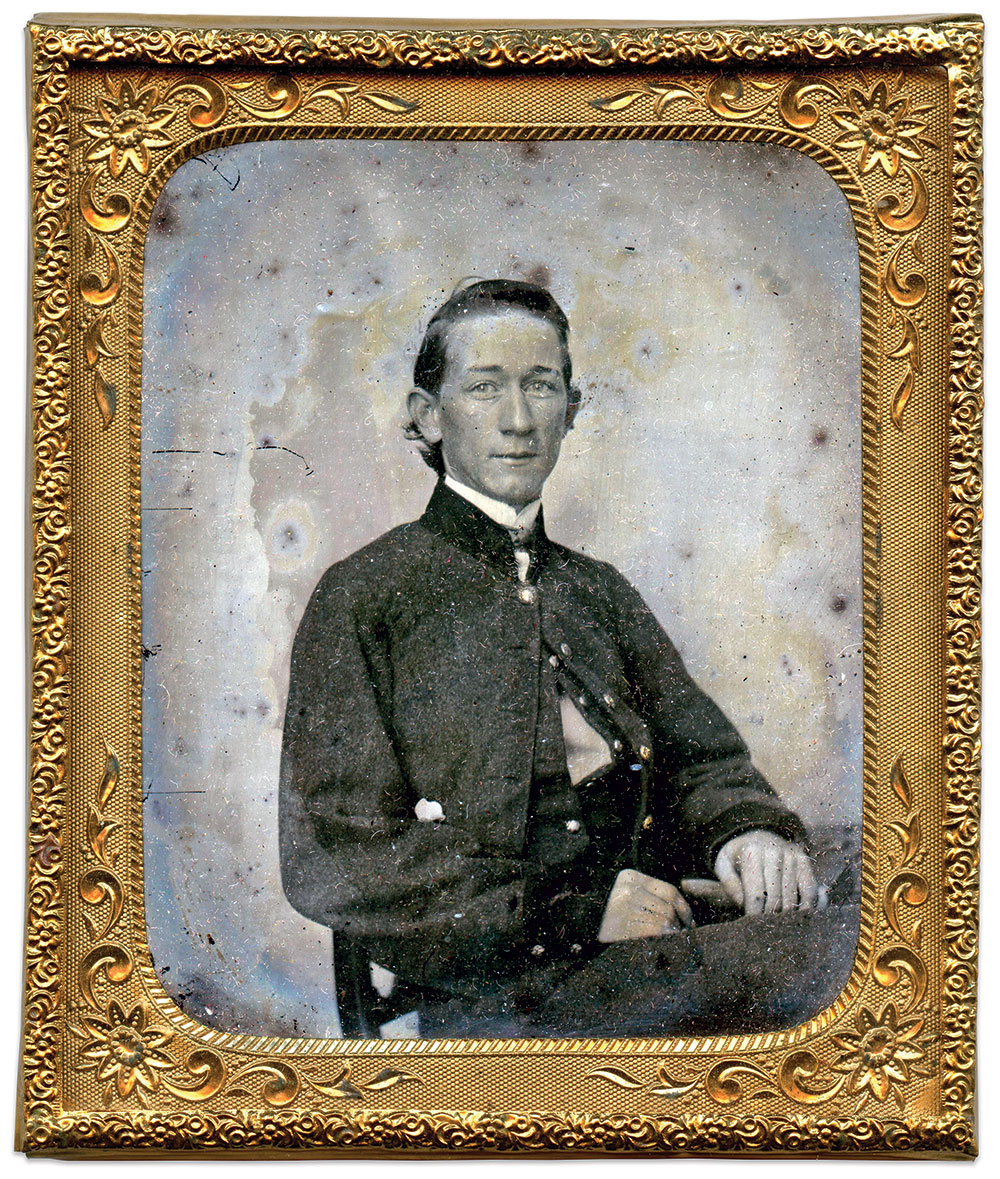

C.R. Rees and Co., by this time probably the largest studio in the city, became especially popular with common soldiers. One can imagine a young recruit eager to have his likeness taken as a memento of his “soldier days,” perusing the showcases set up on the busy street displaying beautiful ambrotypes, picture lockets and cartes de visite of famous generals and heads of government. Cheap prices or possibly a recommendation from a messmate helped him make his decision, and he proceeded upstairs for his likeness to be forever fixed in time.

Opening promptly at 7 a.m., Rees’ studio occupied the top three floors over the Johnston and West bookstore. Once inside, our soldier purchased a numbered ticket denoting the size of the ambrotype: Ninth plate for $1.50, sixth plate for $3.50, and up the scale to as much as $20 for a tinted full plate with a gutta percha case—all payable in Confederate dollars.

Anxiously seated in the waiting room, our soldier adjusted his new uniform and took one final look in the mirror before being called by the photographer. “Next up number 34!” Posed by the busy cameraman and told to “cross your legs, elbow on the table,” the only words necessary. Broken phrases from the developing room might be overheard. “Too dark in the South” or “a ‘little more time’ won’t hurt North,” gave the camera operator direction on the next exposure. All this would be accomplished within 15 minutes and the soldier would have his portrait to show fellow soldiers and loved ones back home.

How to identify Rees portraits

Several methods can be used to identify portraits by Rees’ studio.

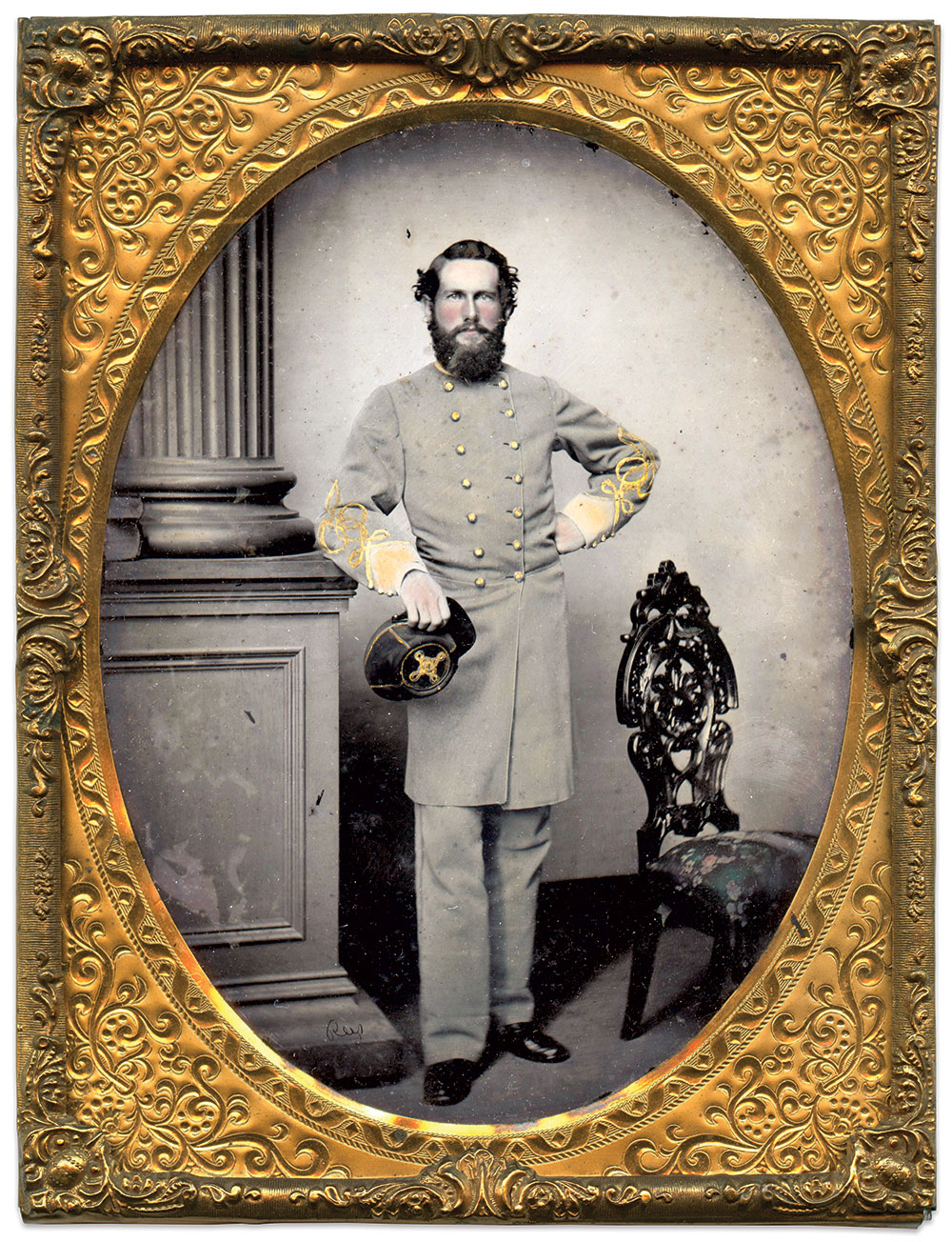

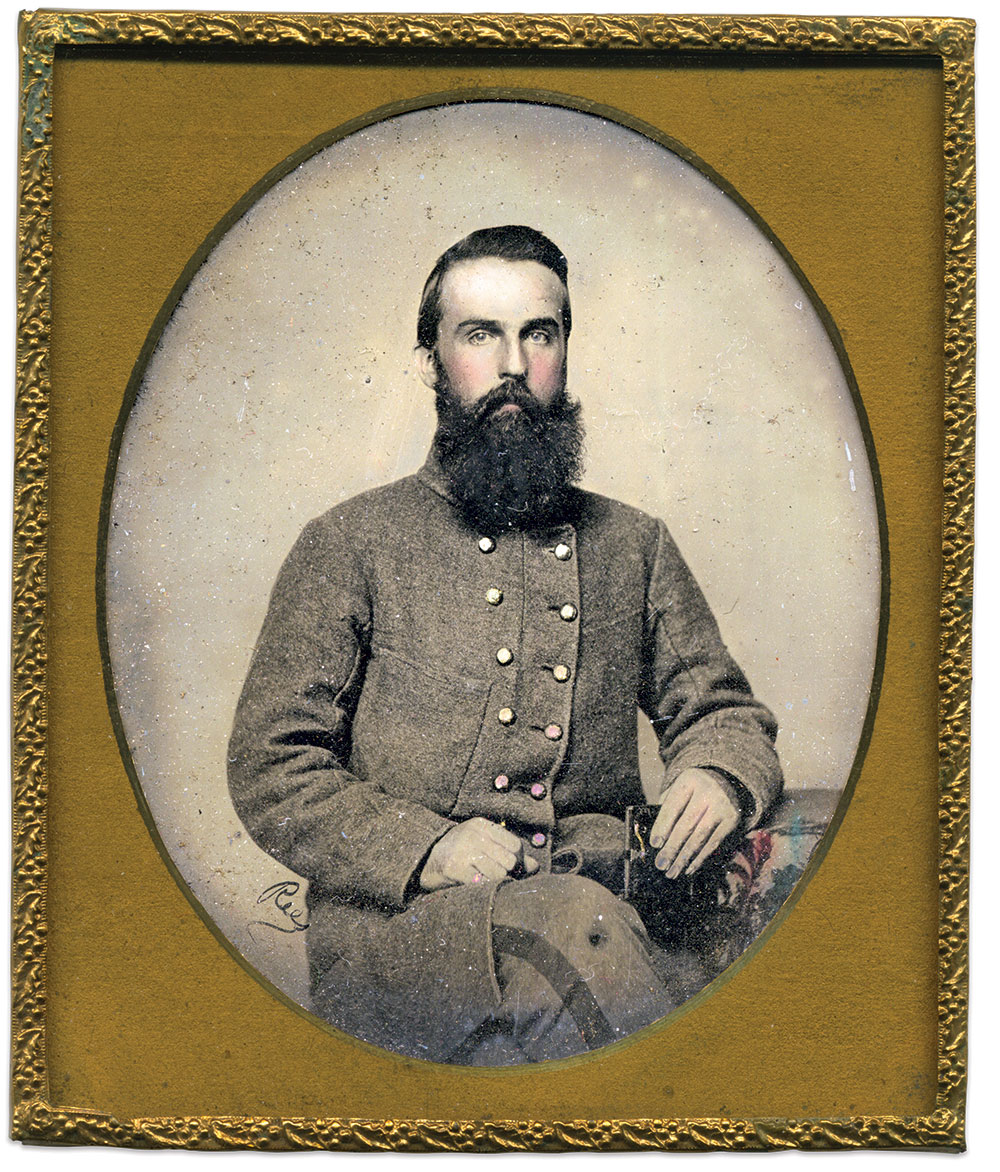

Some of his ambrotypes are signed for reasons unknown. In full-standing portraits, they are often found etched into the emulsion along the bottom of the column pedestal used in his background. In seated portraits, the signature appears in the lower left along the contour of the sitter. There are three variations:

- His last name in script or occasionally block letters.

- The first initial of his last name.

- “Rees Richmond” appears on very few extremely artistic pieces.

The script signature matches samples of Rees’ handwriting. The block letters may denote his younger brother, Edwin, who joined the studio just prior to the war. Rees employed other operators at the gallery, which adds to the mystery.

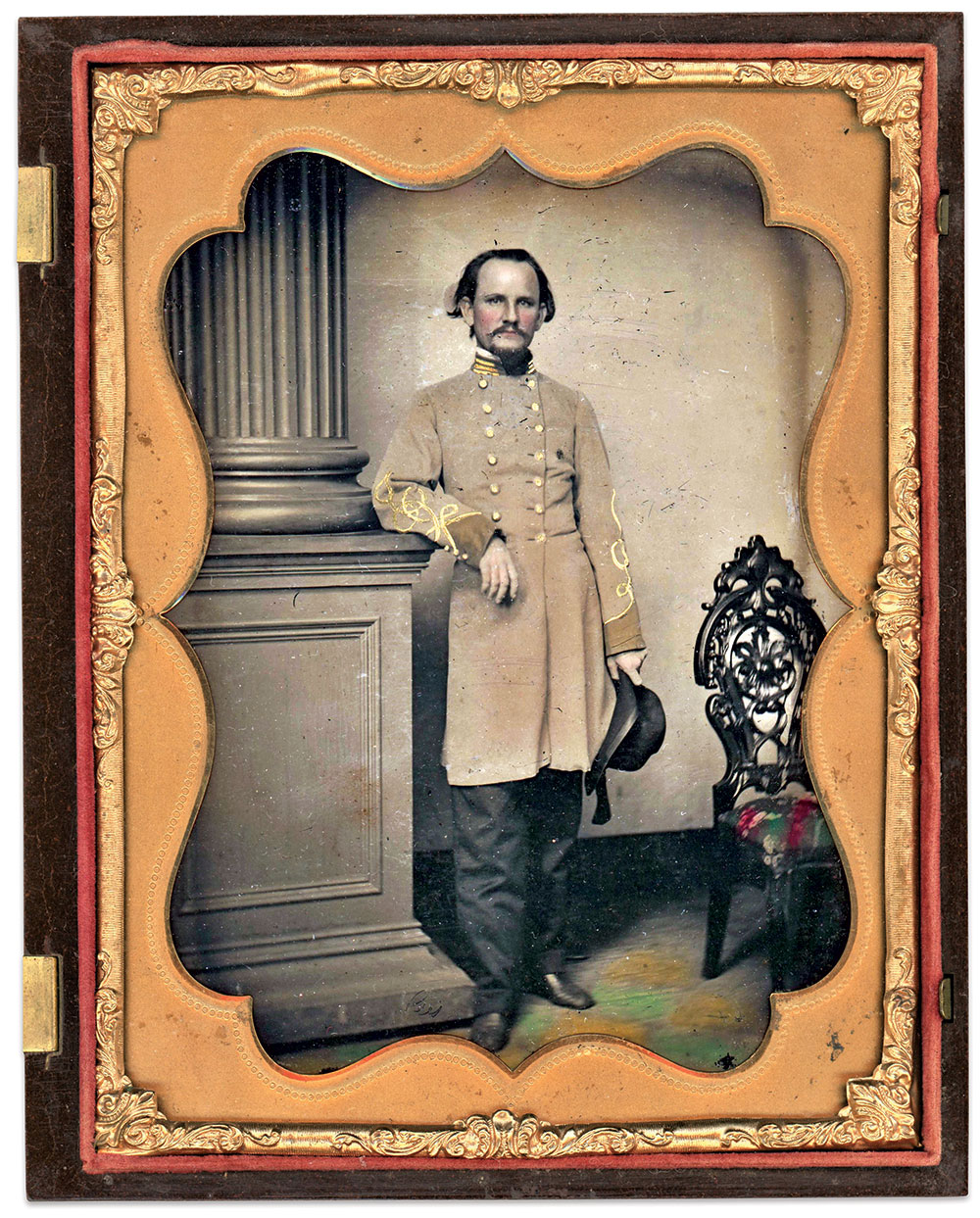

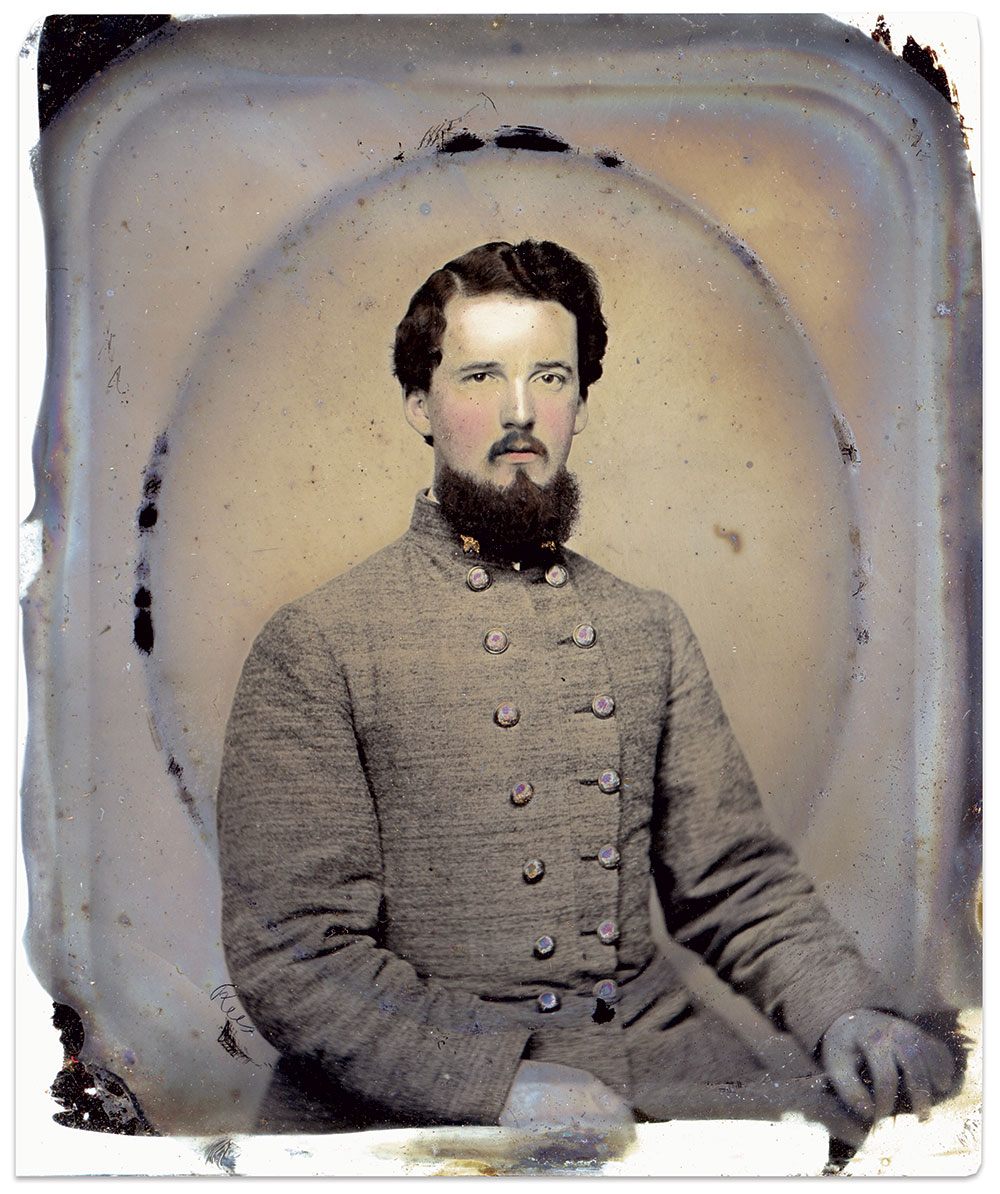

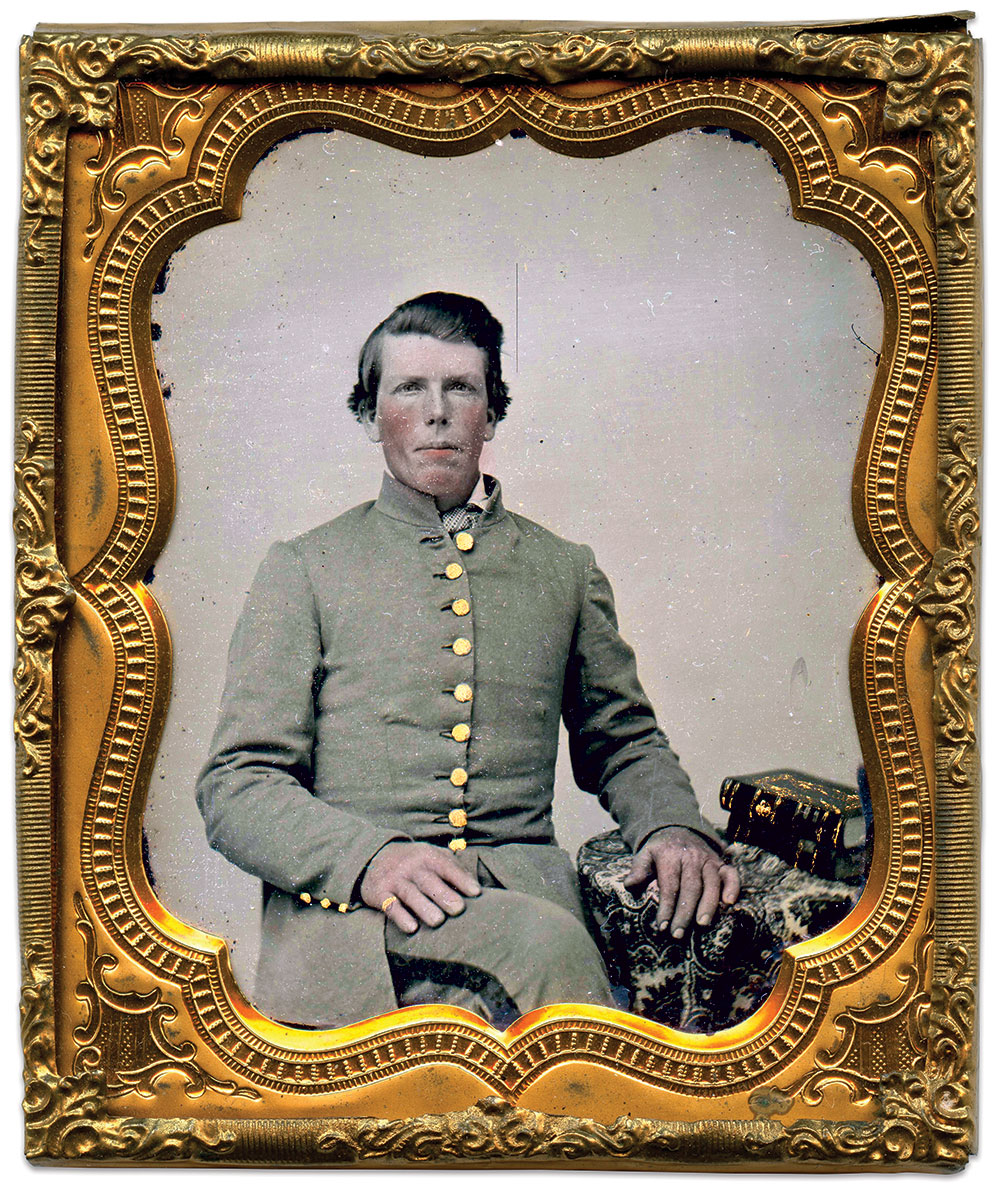

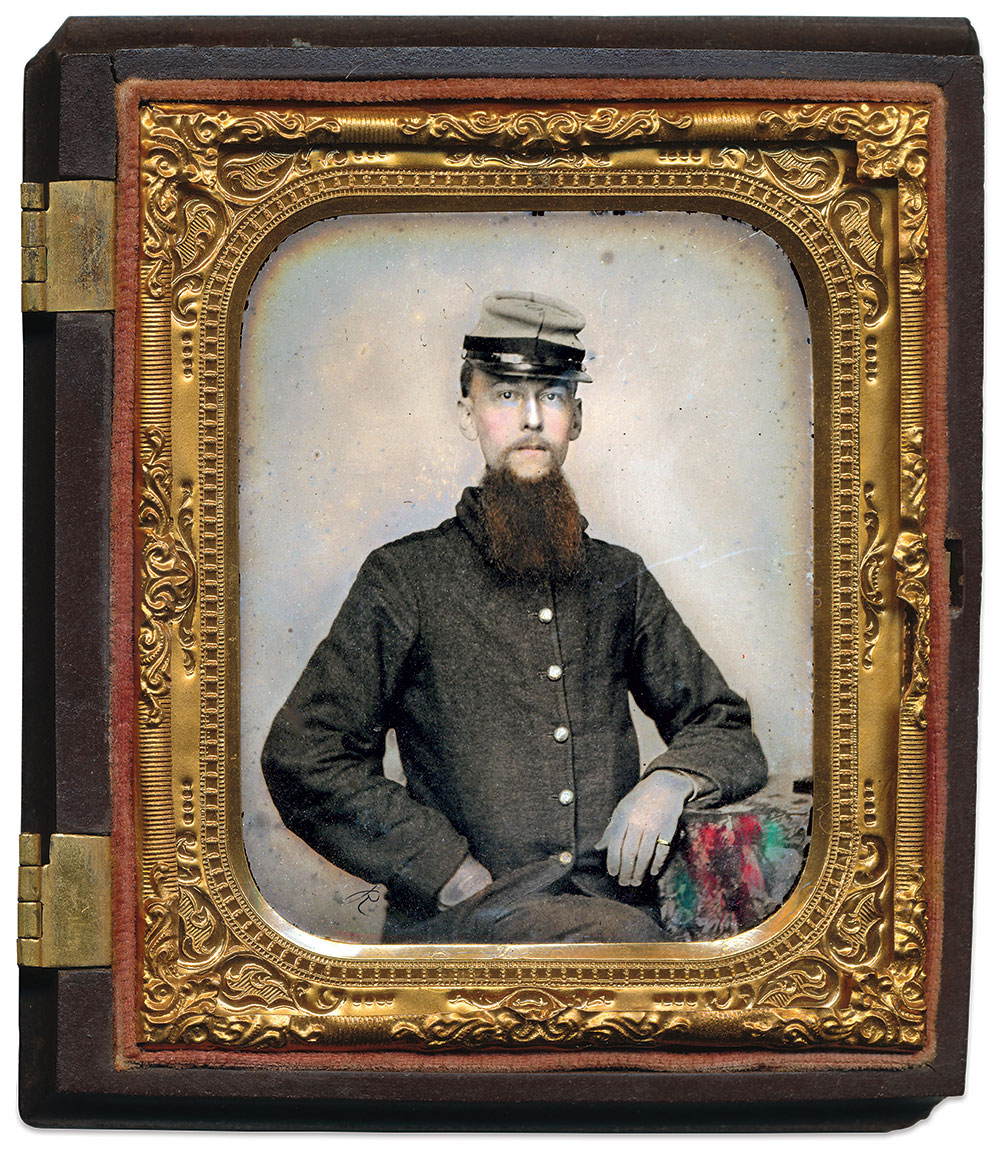

Unsigned examples can be identified with some assurance, though it requires a bit of connoisseurship. Props, poses and tinting are usually all the same with only rare variation. These factors are important clues, but not definitive:

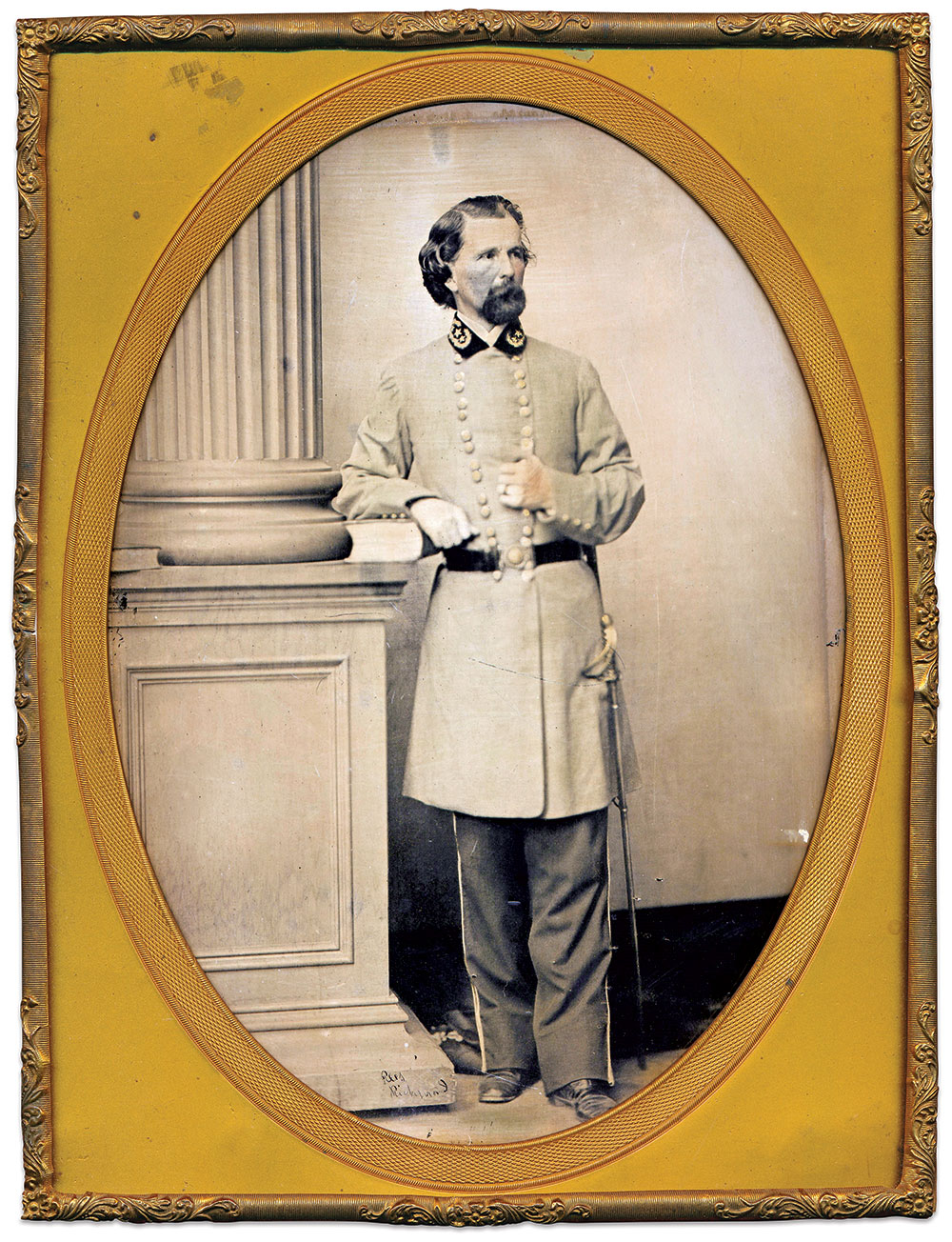

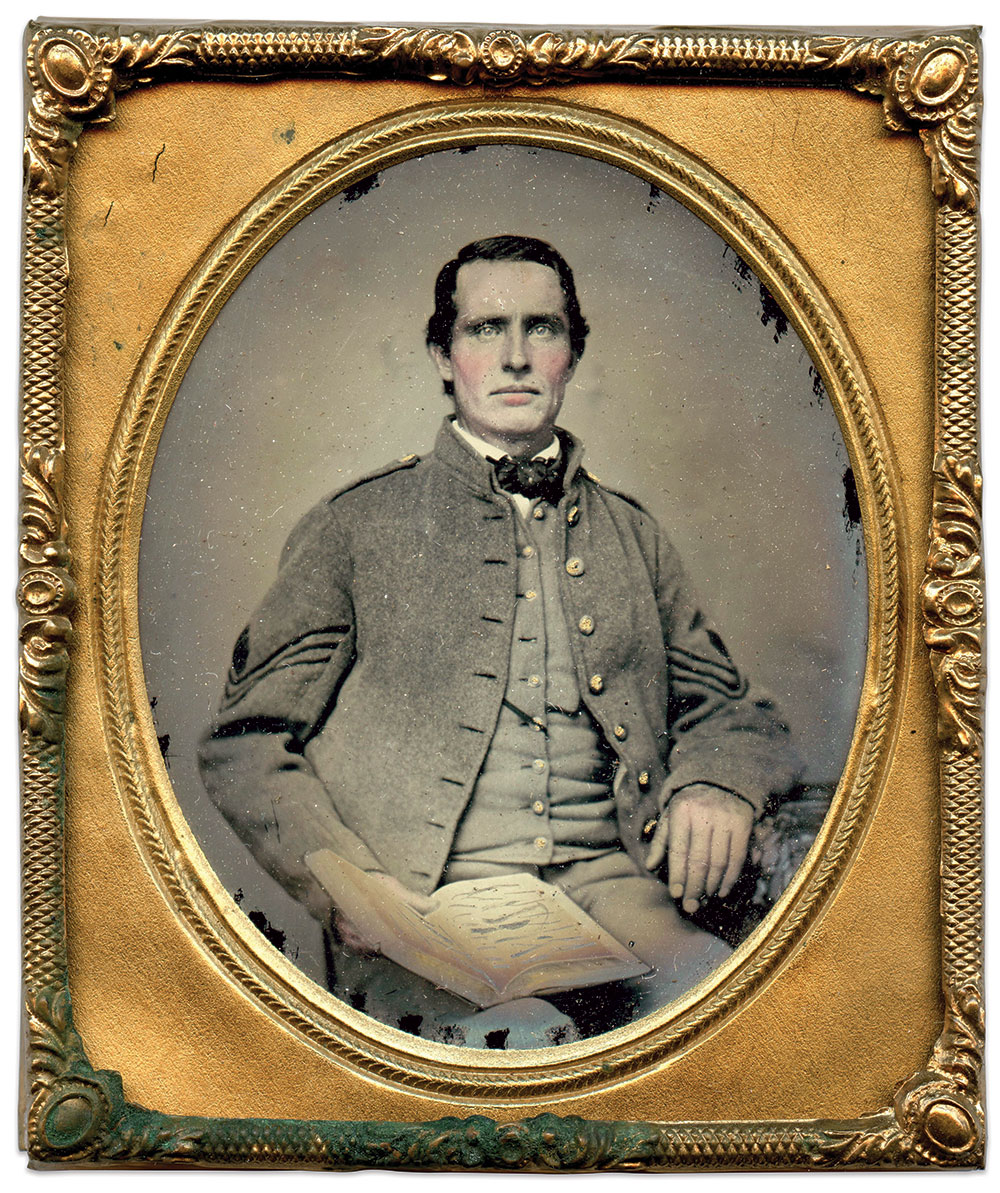

- On ninth and sixth plate seated images, legs crossed facing (reversed) right, elbow resting on a cloth draped table, and occasionally a book is present.

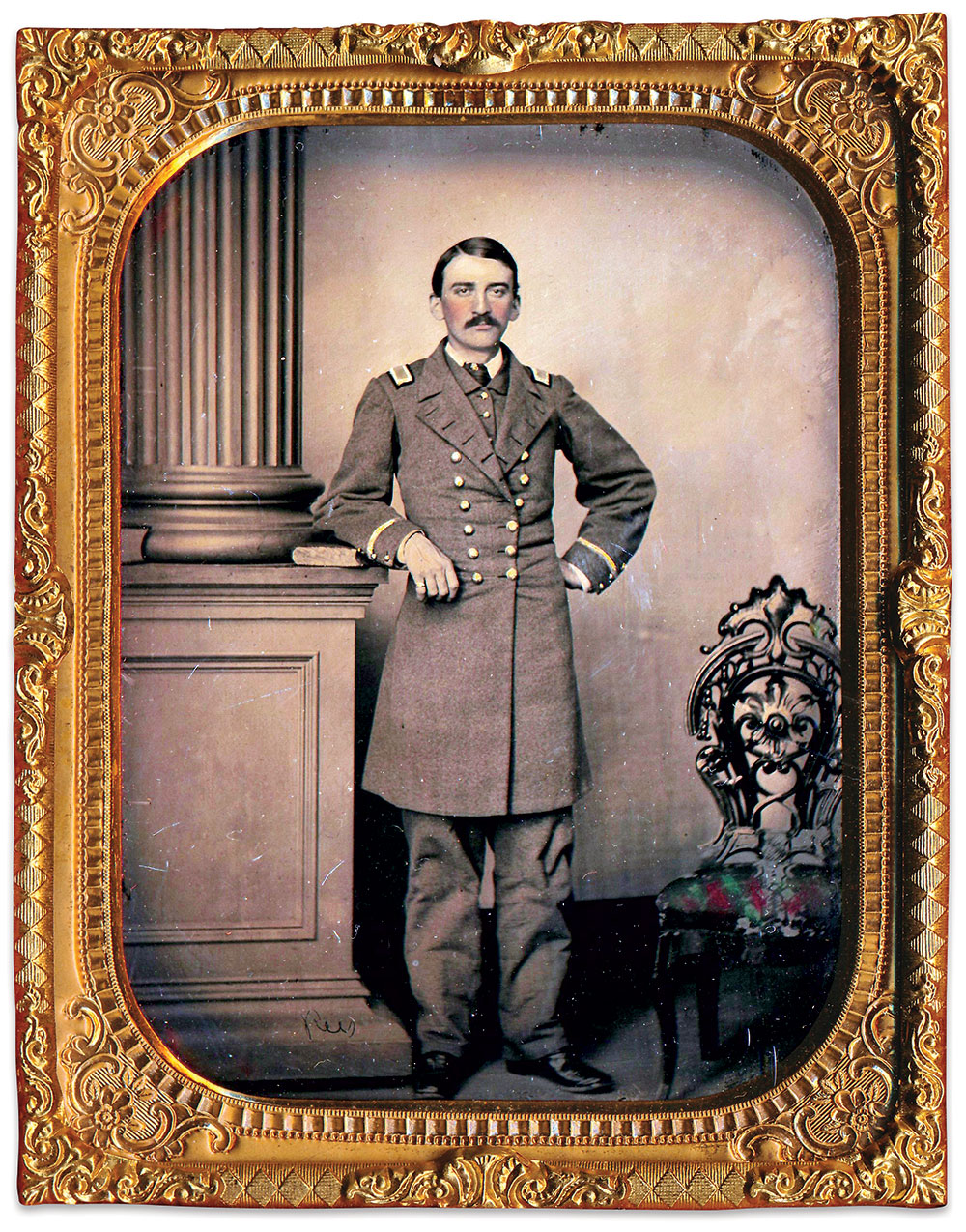

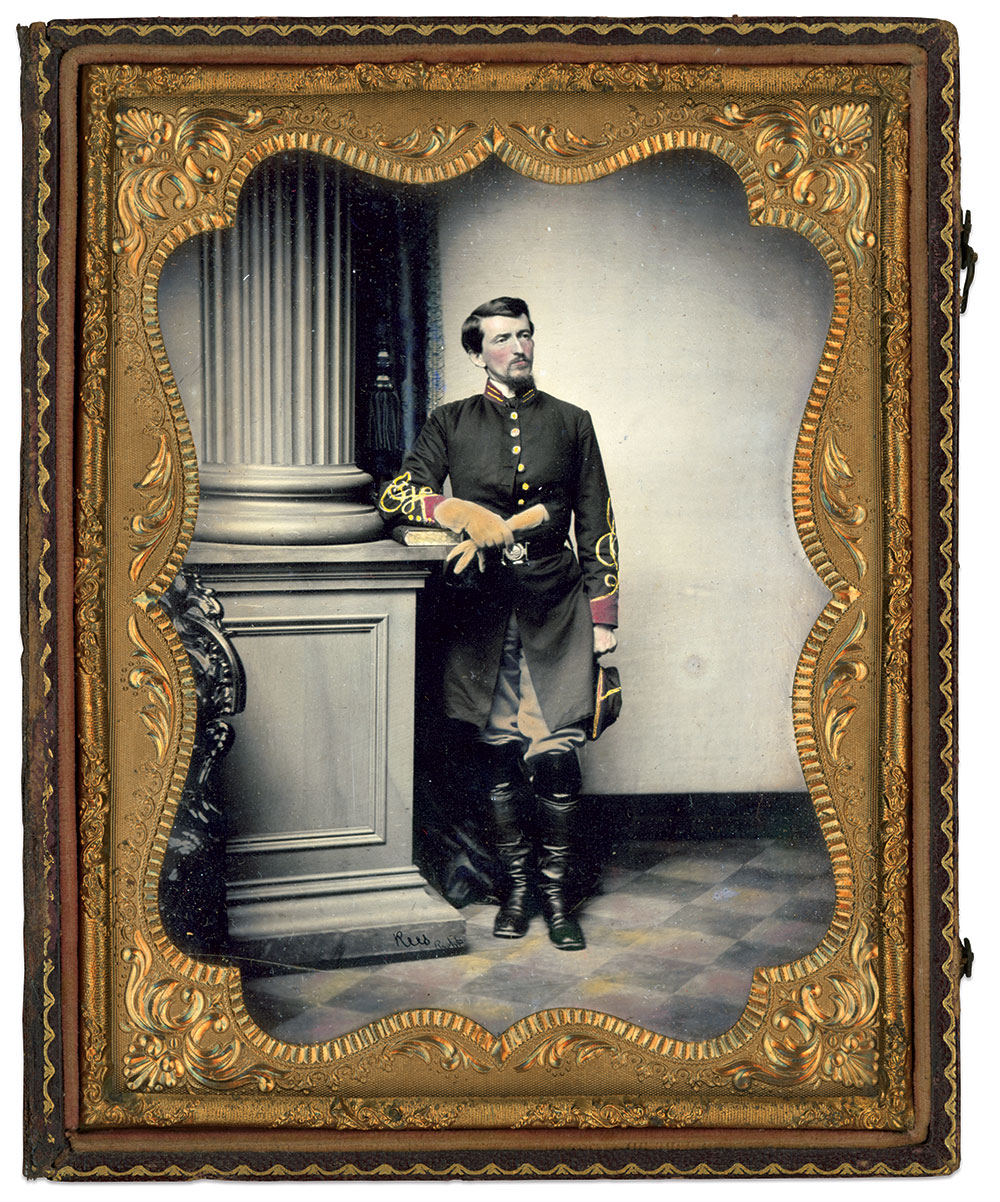

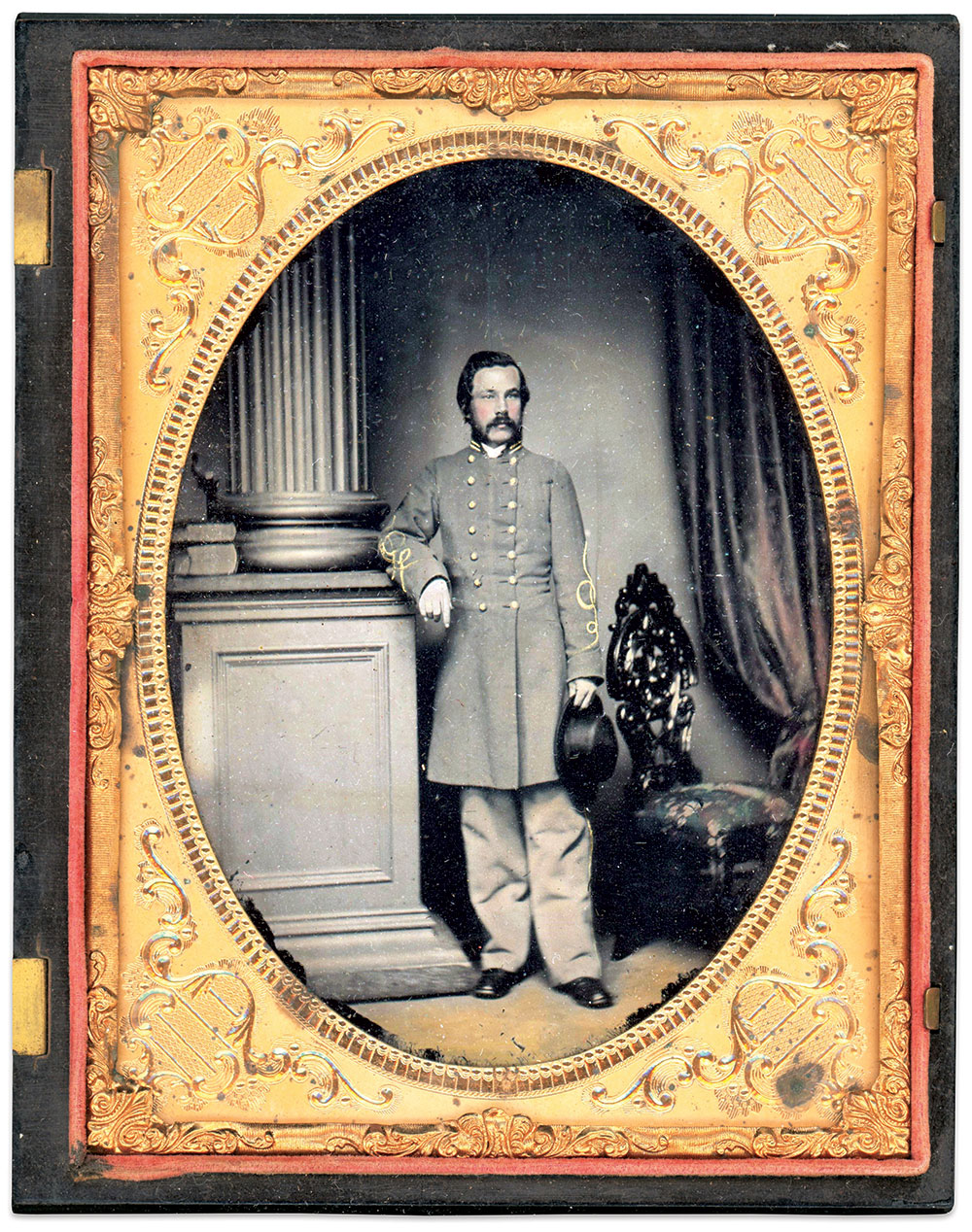

- On larger plates, a standing pose next to a classical column with a Victorian chair balancing the composition. And more books, usually placed on the top of the base that supports the column.

- Tinting is often present on all fleshy parts, not just cheeks.

- The emulsion, which may be best described as a silvery pearl, creates an almost three-dimensional effect that is unique and sets Rees apart from other artists.

The vast majority of surviving ambrotypes ascribed to Rees & Co. were created early in the war, from spring 1861 to summer 1862. During this time Confederate money had buying power, so photography was affordable to the common soldier. Also, the large number of troops clustered in and around Richmond during the Peninsula Campaign provided a vast number of patrons.

An abrupt end to boom times

By 1863, the photography business fell into steep decline. Military and financial reversals affected Richmond and the rest of the South. Soldiers who once flocked to Richmond studios were now far away in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, fighting for their lives. The deteriorating economic situation resulted in the daily devaluation of Confederate currency. A local Richmond woman with a husband at the front summed it up perfectly: “You can carry your money in a market basket and bring your provisions back in your purse.”

The flourishing studios on Main Street closed one by one, and photography equipment was auctioned for pennies. Rees faced an additional problem: his age. At 38, he was within the limits for military service. His subsequent enrollment in the 19th Virginia Militia, also known as the 2nd Virginia Reserves, required him to serve on duty in and around the capital. Called up on July 2, 1863, authorities detailed Pvt. Rees to guard the Yankee prisoners captured during the Gettysburg campaign.

Rees worked at the studio and served sporadically until February 1864.

Here’s where our story takes a twist. He disappears. What little we can glean from available sources is cryptic at best. Rees’ brother, Edwin, became the proprietor of the studio, as can be observed on a few cartes from that period back marked E.J. Rees & Co. By this time, photographic chemicals were impossible to obtain in the blockaded South. A desperate Edwin placed ads offering $200 for a quart of pure alcohol and $100 for acetic acid.

In September 1864, the lavish furnishings in Rees’ Grace Street home were sold at auction: Brussel Tapestries, mirrors, his carriage, a rosewood piano and more.

Two scenarios might explain his disappearance.

Creditors, like competitors, were always a problem for Rees. He may have fled Richmond to escape them. However, it seems unlikely he would leave his family behind.

Another possibility was conscription or battlefield service. Unfortunately, militia records for the last months of the war are scant or nonexistent. Later in life, Rees joined Petersburg’s A.P. Hill Camp of the United Confederate Veterans camp, which suggests his service was of importance to him, or perhaps offered potential business opportunities.

Compounding the mystery is the last verifiably dated image taken at the studio during the Civil War: a carte de visite dated Jan. 1, 1865.

The end of an era

The final days of the Confederacy were bleak and devastating for Richmonders. As army and government leaders evacuated the city on April 2, 1865, the fires set in the tobacco factories quickly spread to the business district on Main Street. Rees and the two other remaining photographers in business, Julian Vannerson and George W. Minnis, lost everything.

Postwar Richmond rebuilt quickly, a testament to the resilience of returning Confederate soldiers. Within four months, Rees and his brother returned to business at a new location on Main Street. Edwin eventually left to work at a studio in Petersburg.

Rees’ combativeness also returned. He became embroiled in a quarrel with an ex-partner, W.G.R. Frayser, who described Rees as “not a Richmond man,” inferring a Northern-born Yankee. On a late night in June 1871, someone was seen unlocking the door to Rees’ studio, and, moments later, a fire broke out that destroyed his gallery—the third time he lost an establishment to flames. Rees, a suspect, vehemently denied any involvement.

Rees still had friends. Four years later, after creditors forced the sale of his photographic equipment and 20,000 glass plate negatives, associates pitched in and purchased the items to keep him in business.

By 1880, Rees’ memorable association with Richmond ended. The great artist moved to nearby Petersburg and prospered for the next 34 years. He passed away at his home on Sycamore Street in 1914 at age 89. The honor guard at his funeral included his aged comrades in the A.P. Hill Camp. Rees’ remains rest in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery, next to Minerva, who passed in 1912.

Rees’ eventful life could be reflected in a quote from one of his many advertisements: “It seems that the art has reached its height, but in this age of wonderful inventions we fear to venture such a supposition, we can only say what’s next.”

Special thanks to the collectors and Chris Steele, Nancy Dearing Rosbacher and Howard McManus for assistance with the Rees timeline.

Dominick A. Serrano is the author of Still More Confederate Faces and has written several articles on Confederate images and uniforms. He lives with his family in Long Island and really enjoys seeing all the friends he’s made through the years of collecting at Civil War shows.

A gallery of Rees images

This unidentified captain of artillery would likely have commanded a battery during the war.

One would never imagine glancing at his elaborate uniform that Thomas Roberts Baker began his service in April 1861 as a private in the Richmond Howitzers. A prominent Richmond pharmacist before the war, authorities detailed Baker to the General Hospital at Biglers Mill as a druggist in July. A year later he was discharged from the Howitzers and served the rest of the war as a hospital steward. Baker continued in the pharmacy business after hostilities and become wealthy selling the very popular Meade and Baker Carbolic Mouthwash. He died in 1906 and is buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery.

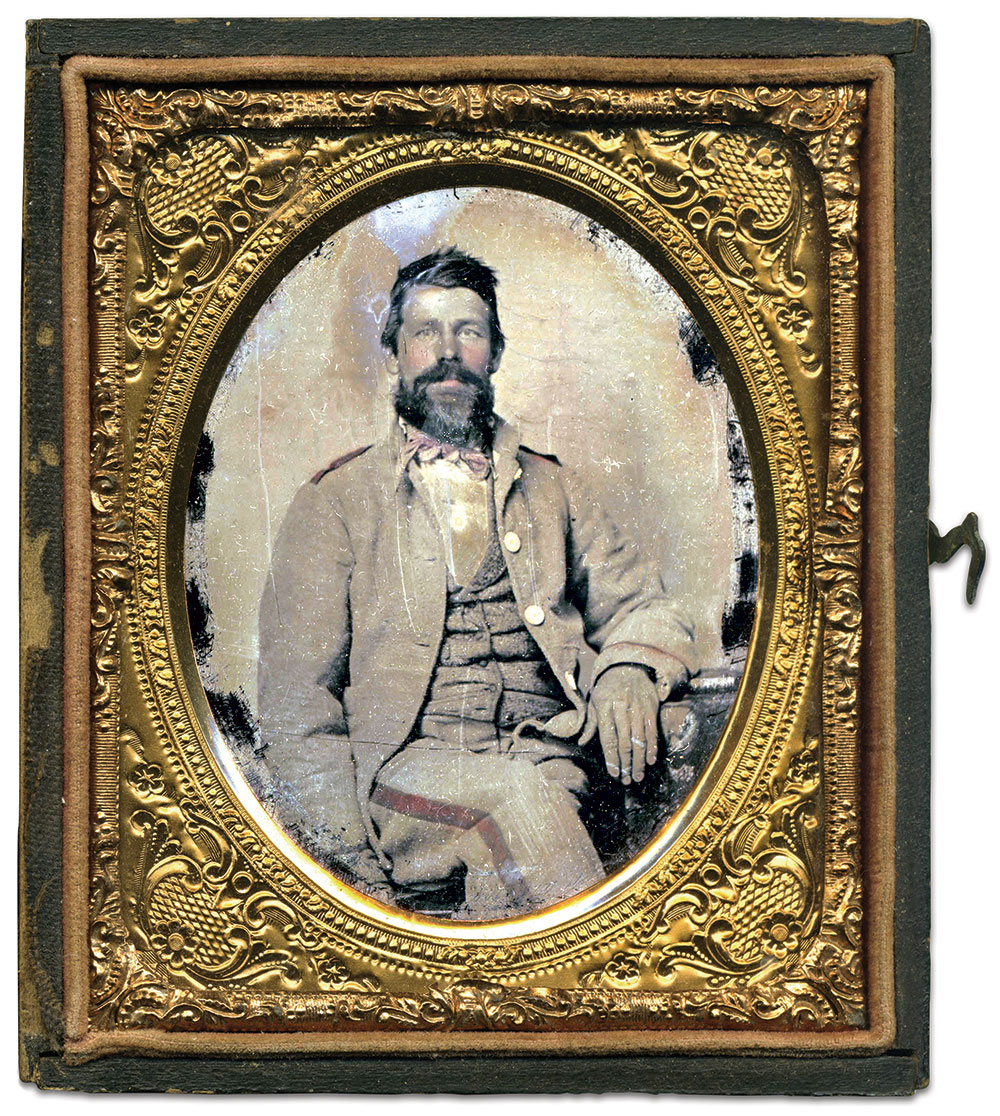

Irish-born Andrew McGowan served faithfully as a private in Carpenter’s Battery from April 1861 until being shot in the elbow at Mine Run in November 1863. While in the hospital at Staunton recuperating Union forces captured McGowan and sent him to Fort Delaware, Del. Slated for exchange, he died of consumption at Point Lookout, Md., on Feb. 17, 1865.

Hailing from Manchester, Va., George Washington Hancock answered peacetime physician-turned artillery Capt. William W. Parker’s call for recruits in February 1862. Parker’s appeal for “Honest, sober men, no one need suffer in his morals” quickly filled the ranks with some of the best and brightest young men from Richmond and its environs. Parker’s Battery became forever known as the “Boy Company” although the statistics show the average age was a bit over 25.

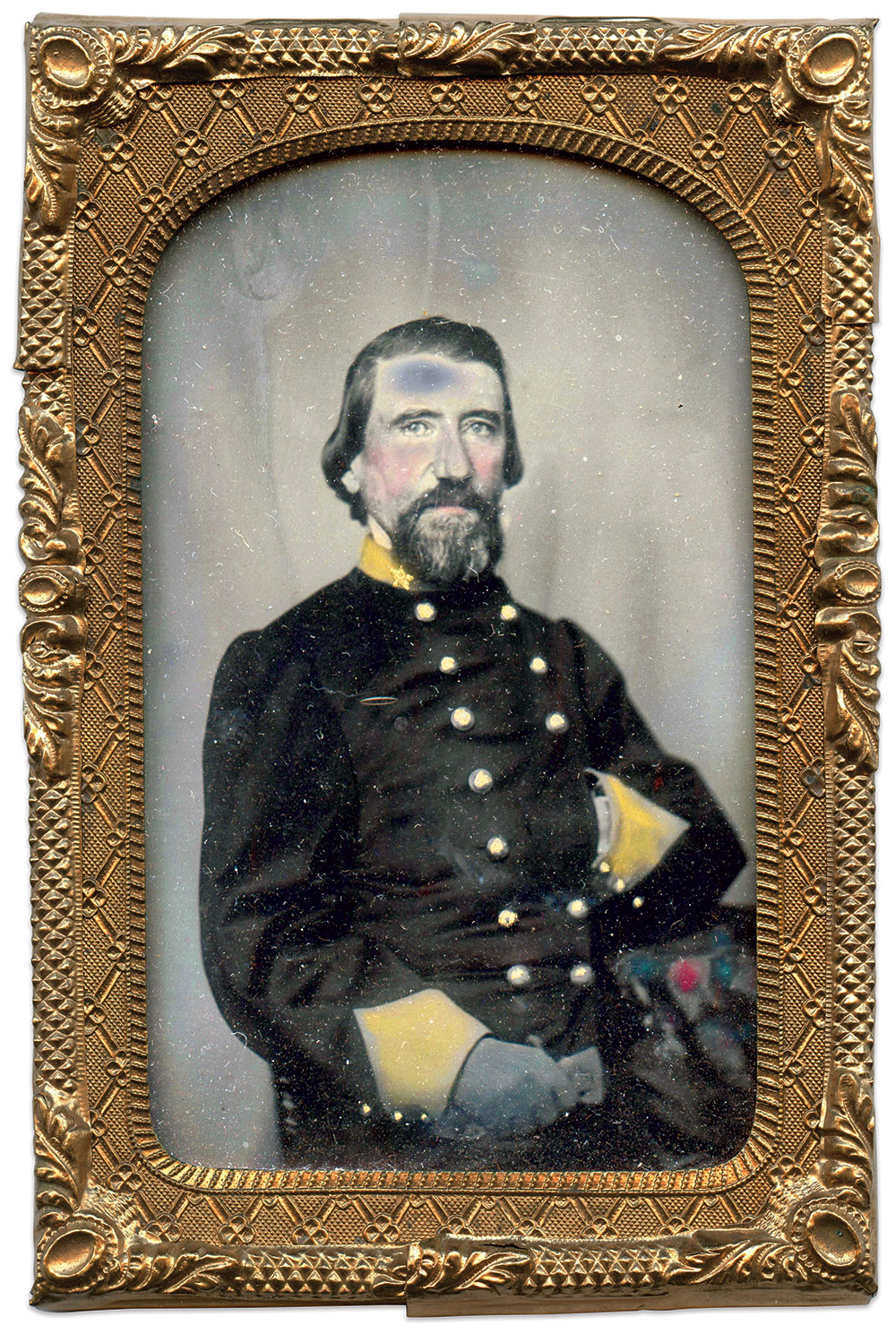

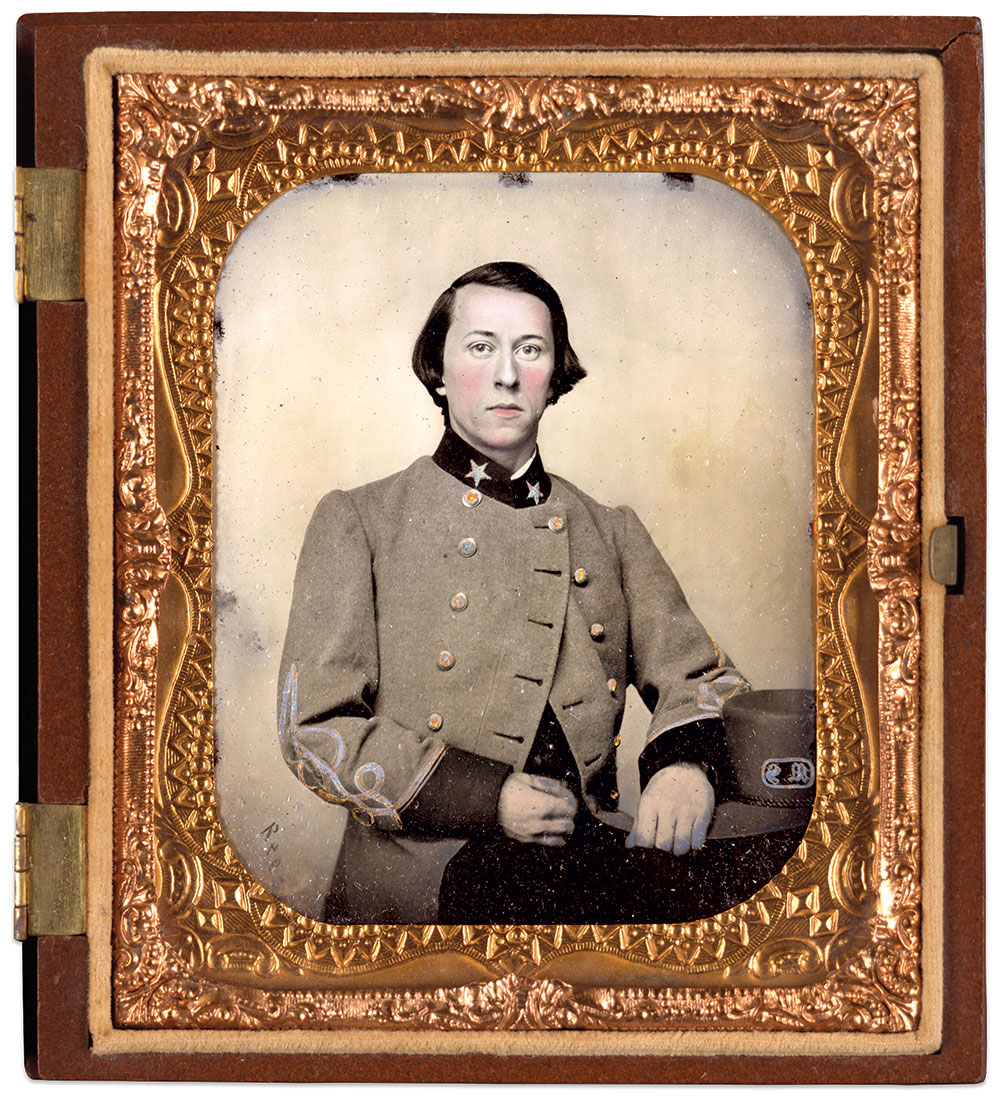

McHenry Howard hailed from one of the most illustrious families in Maryland. His grandfather, Francis Scott Key, wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” and his other grandfather was Revolutionary War hero and past state governor John E. Howard. The youngest of six brothers who served the Confederacy, Howard is best remembered for Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer Under Johnston, Jackson and Lee. The book remains one of the finest post-war reminiscences of the Army of Northern Virginia. A profile of Howard, “Exiled Marylander: The life and services of McHenry Howard,” by Evan Phifer appears in the Autumn 2017 issue of MI.

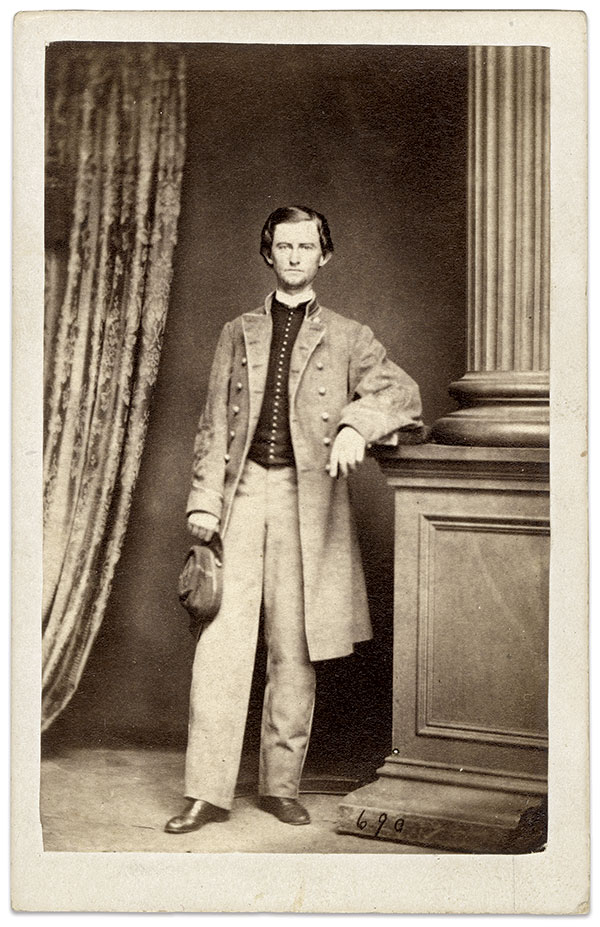

Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman of Maryland stood for his portrait in the late summer of 1862. The Rees signature is in its usual spot along the base of the column with the uncommon addition of “Richmond.” Tilghman’s military career had been marred by controversy at forts Donelson and Henry earlier in 1862. Trying to save his command from almost sure destruction, he abandoned the forts and attempted to break out of Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s siege. The attempt failed, and the federals captured Tilghman and most of his men. Held at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, Tilghman was exchanged in August 1862 for Union Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds who had been captured at Gaines’ Mill. Neither of these brave adversaries survived beyond 1863. Reynolds died on the field at Gettysburg and Tilghman at the Battle of Champion Hill. While directing a battery in the heat of an artillery duel, Tilghman reportedly remarked, “I think they are trying to spoil my new uniform.” Suddenly, a solid shot passed through his body nearly cutting it in two. He was 47.

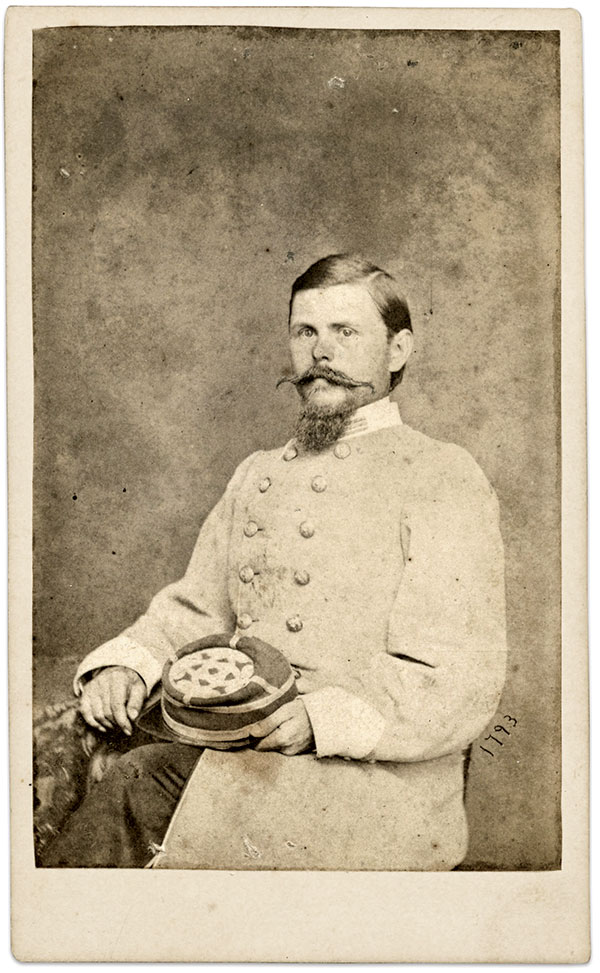

This very rare size Rees ambrotype pictures preacher and religious newspaper publisher Rev. John G. Parrish who served in all three branches of the army. He started the war as a captain in the 47th Virginia Infantry. But the men of the regiment in the 1862 reorganization did not reelect the stern disciplinarian. Desperate for military duty, Parrish appealed directly to President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin for any command. “I know I can render good service to my country and equally desire to contribute my mite in her hour of peril.” His pleas were answered with a captaincy in McIntosh’s Artillery Battalion.

Parrish sat for this portrait in late summer or early fall of 1863, when he received a promotion to major of commissary and transferred to W.L. Jackson’s Cavalry Brigade—making it the latest known ambrotype in this grouping. He served the remainder of the war in this capacity. After hostilities ended, the pious Parrish returned to preaching the word of God in Caroline County until his death in 1871 at age 53.

Yellow-tinted cuffs denote this captain’s cavalry affiliation.

As treasurer of Richmond’s Galego Flour Mills before the war, George Annesley Barksdale was a perfect candidate for a captaincy in the Quartermaster’s Department. Serving first with the 16th Virginia Infantry, he was later assigned to the government payroll department in Richmond. Capt. Barksdale surrendered with the rest of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

The owner of this ambrotype discovered Rees’ signature hidden beneath the brass mat for the last 160 years. This unidentified major’s homespun coat reveals another pleasant surprise—Georgia state seal buttons.

Member of the Stonewall Brigade: A blacksmith by trade, Charles Lewis Jackson Ashby rushed to the colors during the first week of the war when he joined the Clarke Rifles, which became Company I of the 2nd Virginia Infantry. The regiment experienced hard fighting in the command of Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s Stonewall Brigade. Following the Battle of Gettysburg, Charles was fined five dollars for losing his bayonet—a penalty levied by both armies for equipment losses.

After the Battle of Spotsylvania in 1864, the legendary Brigade mustered only 245 men. Ashby numbered among the casualties after falling into enemy hands. Sent to Fort Delaware, Del., he remained a prisoner until exchanged in March 1865.

Ashby returned to smithing after the war and fathered six children. He passed away in 1916 at age 82.

A single stripe on the sleeve and plain shoulder straps of this unidentified Naval officer signifies his rank as a master’s mate in line for promotion. The C.S. Navy maintained a base at Rocketts Landing and a Naval Academy at Drewry’s Bluff, a few miles from Richmond.

This jaunty young man’s kepi displays the letters RFA, denoting his membership in the Richmond Fayette Artillery. A pre-war unit formed in 1821 as the Richmond Light Artillery, its name changed after the Marquis de Lafayette visited Richmond in 1824. During the war, it mustered as Battery I of the 1st Virginia Artillery and fought in numerous engagements, including Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Sailor’s Creek and Appomattox.

The first sergeant’s insignia of three chevrons and lozenge is visible on the Richmond Depot shell jacket of Meredith Fleming. He had been promoted to this rank on Nov. 2, 1862, and he may have sat for his portrait that winter. A member of the Lee Rangers, Company H, 9th Virginia Cavalry, Fleming participated in J.E.B. Stuart’s many exploits until captured on April 3, 1865. Fleming later became Deputy Sheriff of Richmond.

Wiley Hunter “William” Griffin worked as a wholesale grocer in Baltimore before secession and departed the city for his native Virginia at the war’s onset. He and others who had left the Old Line State formed the nucleus of the Maryland Line, a small yet stalwart addition to the Confederate Army. Elected a first lieutenant in the Baltimore Light Artillery, he posed here at this rank. Griffin advanced to captain after the Battle of Antietam.

Less than two years later during J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry fight at Yellow Tavern, Griffin and his artillerists faced peril in the form of charging Yankee horsemen. According to The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, 1861-1865, “the brave fellows never flinched, and served their guns with great effect.” Just before he suffered a mortal wound, Stuart ordered, “Charge, Virginians, and save those brave Marylanders!” It was to no avail. The Union cavalrymen overran the battery and, in the onslaught, captured Capt. Griffin and four of his guns. Sent to Fort Delaware, Del., he numbered among the group of 600 prisoners sent to Morris Island, S.C., and used as human shields to counter a similar move by the Confederates. Griffin and his fellow prisoners, all officers, became known as the Immortal 600.

Griffin survived his war experience and became a grocer in Galveston, Texas, where he died in 1896 at about age 60.

“A bad picture for a good friend” is penciled on the back of this carte de visite. The sitter is future poet and newspaper editor Henry Thompson Stanton (1834-1898). He likely posed for this portrait in May 1864, when he briefly visited Richmond to attend a military court. Stanton served as a staff officer throughout the war but is best remembered for his poem “A Moneyless Man” written just after the conflict.

Rees achieved amazing contrast and depth of field with a unique combination of chemicals in his emulsion. Along with Silver Nitrate, he was known to use Chloride of Gold, Potassium Bromine and Crocus Iodine, which might provide the secret formula. Under this chin-whiskered soldier’s right (reversed) elbow is a simple initial R for Rees.

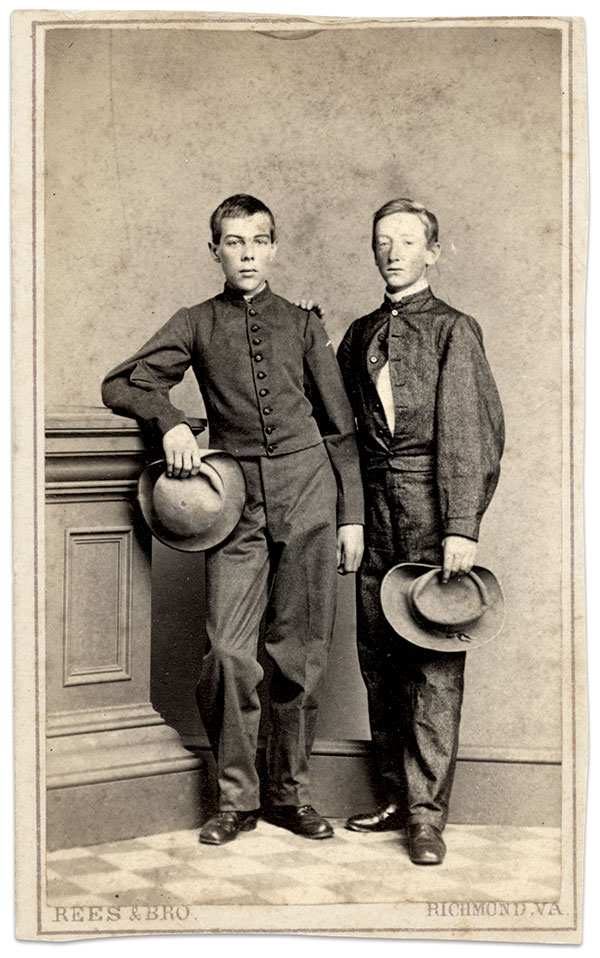

One of the earliest clients of Rees’ reopened studio, 17-year-old James Temple Doswell, left, and an unidentified companion posed for this portrait on Aug. 30, 1865, five months after the evacuation and surrender of Richmond. On the back of the mount, a five-cent revenue stamp canceled on that date denotes a payment of 50 cents to one dollar for the carte de visite. Rees always charged extra for additional people in a picture.

Doswell served in the 3rd Battalion, Richmond Local Defense Troops, a unit raised late in the war of boys aged 15 to 17 and men too old for conscription. Called up during the evacuation of Richmond, the 3rd plodded out of the city on the night of April 2 with Lee’s army. Four days later at Sailor’s Creek, Union forces captured the entire Battalion, including Doswell.

After the war, Doswell became a cotton broker in Texas. He eventually returned to Virginia and died of La Grippe (influenza) in 1890.

Virginian Edmund Louis Massie posed in his splendid new uniform early in 1862 before his departure to the Trans-Mississippi Theater. Massie’s career might make today’s medical students envious. The 22-year-old had graduated from Columbia College, today’s George Washington University, only months before sitting for this portrait. Appointed surgeon in the Confederate Provisional Army, he joined Brig. Gen. Albert Pike’s staff as medical director. The close of the war found the young doctor in Houston, Texas, where he remained for the rest of his short life. He died at his home from inflammation of his stomach in 1872 at age 33.

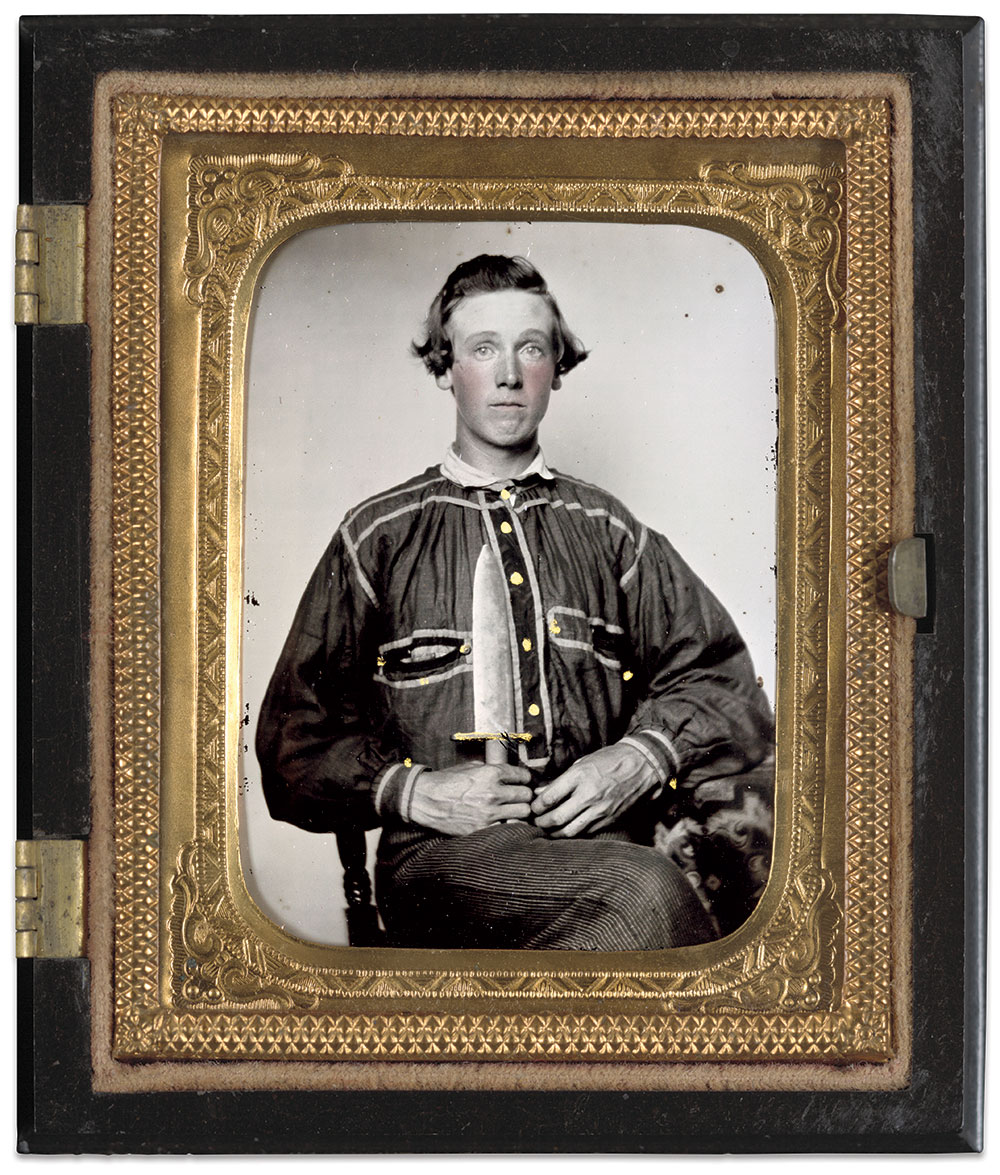

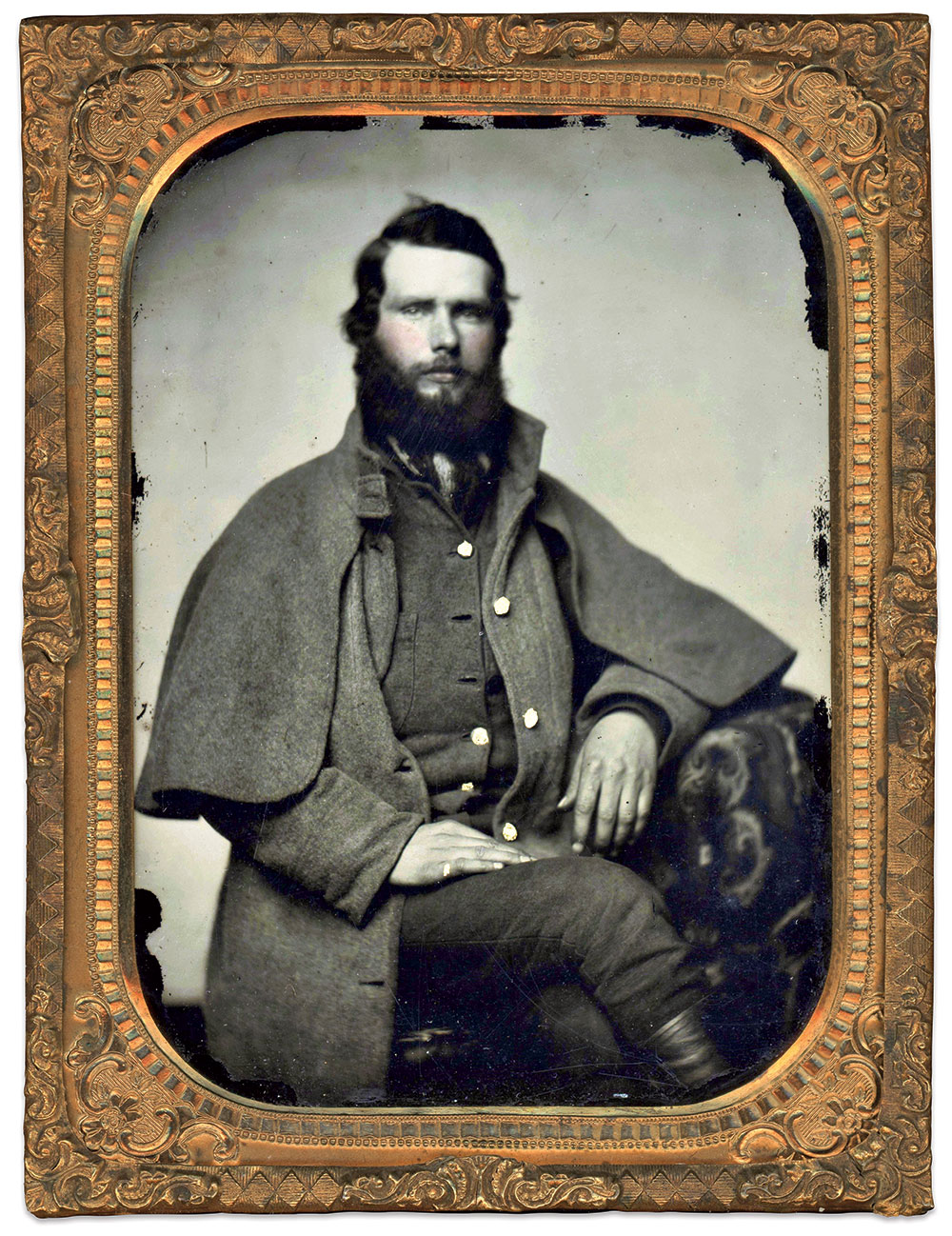

Armed with a Bowie knife and dressed in an overshirt, later known as a battle shirt, was all this early war recruit needed to fight Yankees.

By the summer of 1863 the average Confederate soldier’s pay amounted to 11 dollars, which left little for anything but necessities. Few hard images can be traced to the last two years of the war from Rees’ studio, and it seems the output focused more on cartes de visite, which were easier to produce with the products available—and less expensive for the soldier. This unknown officer posed amid the familiar studio backdrop.

Like so many teenagers from Richmond, 16-year-old William R. “Billy” Burgess left his family to join one of the many artillery units formed in the city in the spring of 1862. He enlisted at Messr. William Crenshaw and Company’s warehouse for three years or the war with “one of the jolliest, most rollicking, fun loving crowd of youngsters, between the ages of 16 and 25 that were ever thrown together,” according to a comrade.

Billy was designated company bugler, and received a new uniform supplied and paid for by Crenshaw, who became captain of the new battery. A week after his enlistment, on March 21, 1862, Billy sat for this likeness. He served faithfully in all 48 engagements of Crenshaw’s Artillery. On April 8, 1865, what was left of the battery “cut down our guns and sorrowfully wended our way homeward.” Billy, and his older brother, Benjamin, received paroles the next week at Burkeville Junction, Va. In later life, Billy worked as a printer in Washington, D.C. He passed away April 20, 1912, 47 years after the surrender.

The cracks in this ambrotype might foretell a malignant omen for this young lieutenant’s future. In the first week of the war, Claudius S. Alexander rushed to enlist as a private in the 4th North Carolina Infantry. He quickly rose through the ranks and is seen here in 1862 as a second lieutenant amidst the Rees studio backdrop. By the spring of 1863, Alexander had attained the rank of captain having avoided injury at Fredericksburg and Antietam. His good fortune ran out at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863. Leading Company C, also known as the Saltillo Boys, he suffered a wound that proved mortal. He died three days later—one of the 46 officers and men killed in the regiment.

One of only a handful of Confederate images shows a Southern soldier wearing what appears to be an English Army overcoat. The C.S. Clothing Bureau imported thousands of greatcoats from European manufacturers during the war and authorized one overcoat per soldier every three years at a cost of 25 dollars.

A dapper lieutenant poses for the camera.

The 4th Virginia Infantry fought in Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s Brigade on Henry Hill during the First Battle of Manassas—where the Stonewall Brigade received its nom de guerre. Among those from the 4th present that day was the enlisted man pictured here, Abraham Gross. A 37-year-old farmer in Montgomery County, Va., he had enlisted in his local militia, the Fort Lewis Volunteers, on April 18, 1861. Gross’s cap bears the company initials, FLV.

Authorities designated the Volunteers as Company B of the 4th and assigned it to Jackson’s Brigade. A year after the fight at Manassas, Gross received an honorable discharge. His discharge paper references the Congressional Act of April 16, 1862, which extended service for Confederate soldiers to three years from the date of their enlistment and instituted a draft for men aged 18 to 35. At 38, Gross may have been discharged due to his age. He remained in Montgomery for the rest of his life, dying in 1895 at age 73.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Rees of Richmond: A fresh look at the combative, competitive and brilliant Confederate photographer Charles Ricard Rees”

Comments are closed.