By Ronald S. Coddington

On a September day in 1864, a Union sergeant stationed at the sprawling military hub in Louisville, Ky., put the finishing touches on a letter.

It was no ordinary correspondence. The soldier aimed his words far beyond the range of artillery bristling from earth and timber forts dug into high points dotting a 10-mile semicircle defending the city.

“It is with feelings known only by those who are true to the cause of freedom, that I address you these few lines in order to illustrate my sentiments on the present important crisis,” began Sgt. Charles W. Singer.

The “you” to whom Singer addressed the letter, Rev. Elisha Weaver, edited The Christian Recorder. Published in far-off Philadelphia, Pa., by the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the influential weekly newspaper’s loyal readership included the rank-and-file of colored regiments.

The “crisis” referred to the stalemate of Union forces in Virginia, a war weary Northern populace divided on whether to fight or settle for peace, and concern about reelection prospects of the President who authored the Emancipation Proclamation.

The future of the nation had arrived at one of its bleakest moments since its establishment four score and eight years ago. The stakes were high. If it fell, the certain destruction of government by the people would follow. If it continued, a mighty step forward towards the more perfect union would ensue as described in The Preamble of the Constitution.

One of the keys to success of the Union military lay in the hands of 200,000-plus men of color that served in the army and navy.

The vast majority of these men and their families had lived in bondage, their human rights decided by masters and mistresses.

A fraction of these men, including Singer, had been born free. A farmer in his early twenties and the eldest of eight children raised by a Covington, Ky., barber and his wife, Singer had no known formal schooling. He may have gained an education at his father’s barbershop. Modern historians recognize such establishments as places for conversation and discussion about community affairs beginning in the turn of the 20th century. The barbershop may have served as a gathering spot before this time, and it is easy to imagine young Singer listening to his father’s clients debate the politics, economics and culture of slavery during the years prior to the war.

No evidence exists that Singer strayed beyond Covington until the army drafted him in May 1864, and assigned him to Company A of the 107th U.S. Colored Infantry. Five months later and 125 miles from home, he wrote to The Recorder. The original letter is lost, but the version that appears in print survives. It is a personal manifesto, a declaration of loyalty, and a public appeal to his fellow soldiers to support the federal government. It gave voice to black men in blue, and millions of enslaved peoples.

Following his brief introduction, Singer proclaimed that personal liberty lay at the heart of the matter.

“Freedom! What a glorious word to commence with! I place it above all others, except my God. I never was a slave; but my imagination furnishes to me a picture, which must approximate somewhat to the reality of that miserable condition. I sincerely and candidly think that every man in the North should, to the fullest extent of his abilities, aid and further the cause of freeing the slaves, now held in bondage by Southern tyrants. … To this appeal some may answer: ‘What do we want to fight for the slaves for? Let them win their own freedom.’ To all such I would say, make an imaginary exchange of conditions with those poor, down-trodden and degraded slaves at the South, and then would you not think it very hard for others to tell you to help yourself, and get out of it the best way you can? Most assuredly you would. We should not forget the fact that the free colored man’s elevation is at issue, as well as the slave’s. Suppose the rebel army was as far North as the Union Army is South, what would be the result? I will tell you. Our homes would be burned to the ground, and our aged and defenceless parents barbarously treated. Rather than have such outrages perpetrated, I would remain in the army the rest of my life.”

Singer reminded readers of the high stakes involved.

“Should this Government be overthrown, the experiment of civil and religious liberty will be overthrown with it. The Government was begun under the most auspicious nature. We are in the vigor of youth. Our growth has never been checked, not even by the oppressions of slavery. Our constitutions have never been enfeebled by the cruel treatment of rebel tyranny. Such as we are, we have been from the beginning—hardy, intelligent, accustomed to self-government and self-respect, and that is all I ask. Forbid it, my countrymen, that we should have less. … Some say that the present conflict is irrepressible. I beg to differ on the subject. I call upon you, brethren, to resist all encroachments upon your liberties—every attempt to fetter your consciences, or smother your public schools, or extinguish your system of public instruction. When I say, resist, I suppose you will ask, Against whom? I answer, those cowardly copperheads of the North.”

Singer appealed to families for support.

“I call upon mothers, by that which never fails in women—the love of your offspring—to teach them, as they climb your knees or lean upon your bosoms, the blessings of liberty. I call upon you, old men, for your counsels and your prayers. May not your gray hairs go down, in sorrow, to the grave, with the recollection that you have lived in vain! May not your last sun sink in the South, among a nation of slaves?”

He also warned of the danger of underestimating the enemy when he noted,

“Some people assert, that the Slave States cannot furnish as good soldiers as can be produced by the Northern States, because they are not as well educated. Those who think thus have not read much; for history confirms the statement, that unlearned men make the best soldiers. They have stout arms and brave hearts, which is equivalent to education, because it takes the brain to plan, and the arm and heart to execute.”

Next, Singer revealed his own desires.

“I wish for nothing but to breathe, in this land, with my fellow-subjects, the air of liberty. I have no ambition, unless it be to break the chain and exclaim: ‘Freedom to all!’ I never will be satisfied so long as the meanest slave in the South has a link of chain clinging to his leg. He may be naked; but he shall not be in irons. Remember, soldiers, we are fighting a great battle, for the benefit, not only of the country, but for ourselves and the whole of mankind. The eyes of the world are upon us, and on the result depends our future happiness. One portion is gazing with contempt, jealousy and envy; the other with hope and confidence. Do you expect to execute this high trust by allowing yourselves to be trampled down by your enemies in the North? No, we can battle against both; at least, we can try.”

He followed up with a statement of support for and confidence in a government that had as of yet not fully recognized him as a human being.

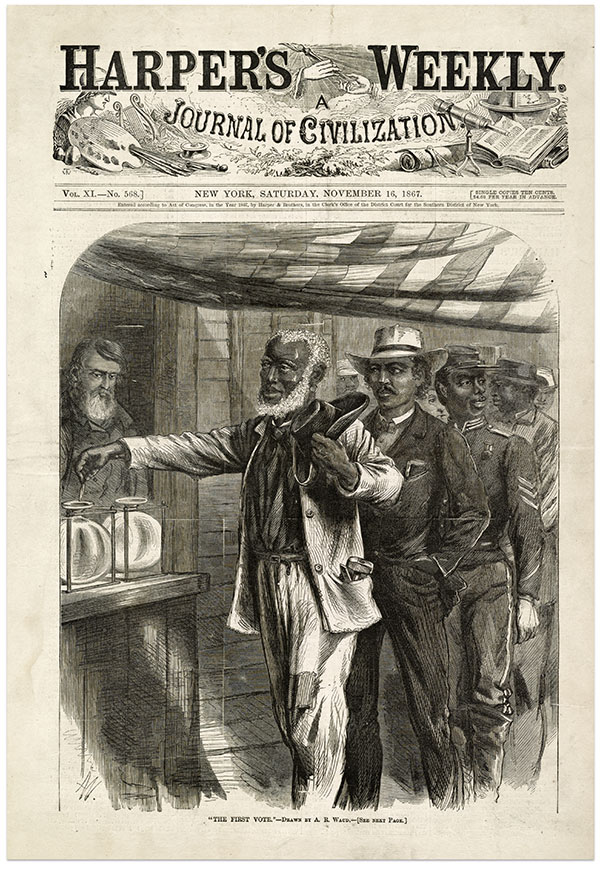

“We have friends in the North, who will help us while we fight the opposers of the Government in the South. I hope that we may never see the day that we cannot speak for the cause of freedom. Why should we not cling, with courage, to this Government—her interests, laws and institutions? There are many reasons for so doing. It is not merely that I am grateful for the protection and citizenship that I may hope for; but I recognize in the stability of this Government a source of strength to other nations. While this Government stands, there is hope for the most abject, disabled and helpless of mankind. Our race may, at some future day, become an independent nation. Should we then ask the protection of the United States Government, we could not, with consistency, be refused if we do our best to aid it in this its time of danger.”

Singer also sought to quell naysayers.

“The question has frequently been asked: What will be gained by the present war? I ask, in return: What will you not lose by a mongrel state of peace? We would lose the best opportunity that has ever been afforded us to show the whole world that we are willing to fight for our rights. Why should not the black slave of the South fight for his liberty as well as the white serf of Russia? A slave is but a slave, and a man is but a man. Age or color is nothing—blood will tell all. … The so-called southern Confederacy is fighting for the establishment of a Government, which will have for its corner-stone the perpetuation of human slavery—the degradation of the many for the purpose of elevating the few; but never shall they succeed so long as I can raise my arm against them. Who ever learned in the school of base submission the lessons of freedom, courage and independence? When did submission to a wrong induce an adversary to cease his encroachments?”

Singer concluded his plea with a vision of America after the guns fell silent, and with the rallying cry of Patrick Henry.

“Some say: ‘Show me what the colored man has to fight for, and then I will go.’ You cannot see it now; but wait until some future day, and it will unfold itself most gloriously to the whole country. We want the rights of freemen, and must have them; but we can never get them if the South gain its independence. If I were now a slave at the South, my motto would be: ‘Give me liberty, or give me death!’ I hope that motto will ring throughout the entire length and breadth of the rebel States, and fire the hearts of the men.”

He ended his letter with family.

“Shall we not console our aged mothers with the hope, that, when hereafter their souls, crowned with the garlands of martyrdom, look down from the home of the blessed, the united joys of the heavens shall thrill through their immortal spirits, seeing their dear people free from the bondage of slavery?”

Singer dated his letter to the editor September 18. By the time it appeared on page 2 of the October 8 issue of The Recorder under the headline “Shall We Sustain the Government?,” public opinion leaned in favor of continuing the war. The fall of Atlanta to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s forces about two weeks before Singer finished his missive reinvigorated the North. Though the situation in Virginia had changed little, it had become clear to many Union patriots that the siege lines surrounding Richmond and Petersburg would eventually choke the life out of the Confederacy.

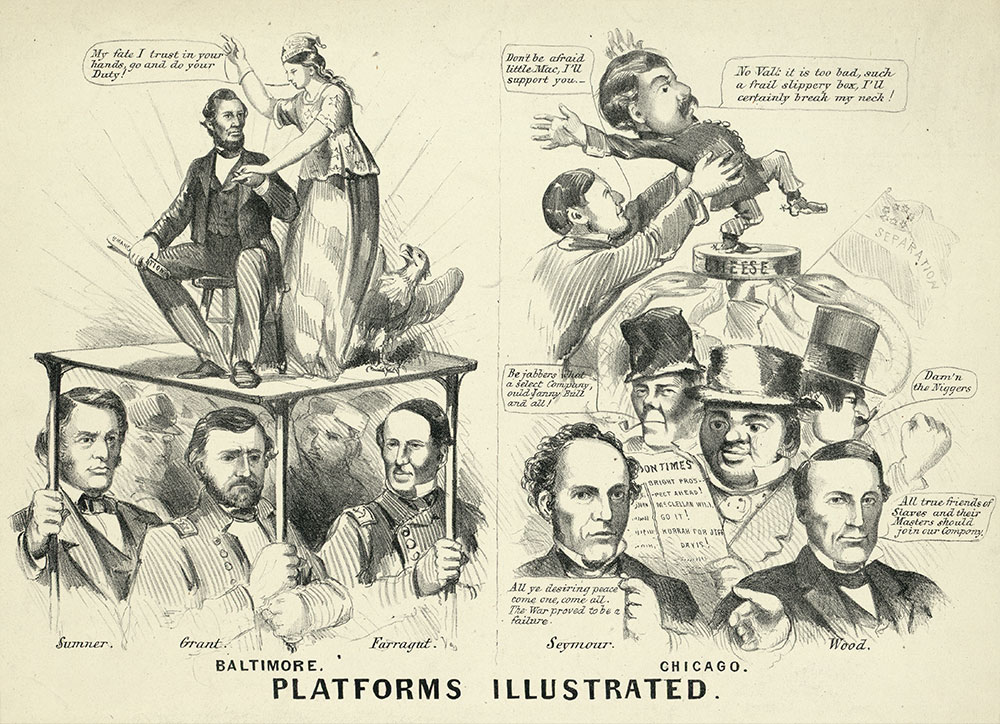

One month later, on November 8, Americans elected Abraham Lincoln to a second presidential term in a landslide. Only three state electors cast ballots for Democratic candidate George B. McClellan: Delaware, New Jersey, and Singer’s native Kentucky.

About this time, the 107th departed Louisville for frontline positions in Virginia. Soon after it arrived, Singer landed in the hospital for treatment of an undisclosed ailment, and then for rupia, a sexually transmitted disease likely contracted before he enlisted.

He remained in the hospital for one year. During his absence, the 107th participated in the 1865 capture of Fort Fisher, N.C., and the Carolinas Campaign, which ended in the surrender of the Confederate armies commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston.

Singer rejoined his comrades in November 1865 and received a promotion to sergeant major. He served in this capacity at various posts in North Carolina and in the military Department of the South until November 1866, when he mustered out with the rest of the regiment.

He settled in Ohio and became a violin player and music teacher in Cincinnati. Active in the Catholic Church, he never married. In the late 1890s, rheumatism and failed hearing forced him to give up his life as a musician, and he became a waiter. Singer entered the Soldiers’ Home in Dayton in 1910, and died there of heart problems five years later at age 75.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI. He first told Singer’s story in his 2012 book, African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album (The Johns Hopkins University Press).

References: The Christian Recorder, Oct. 8, 1864; “The Community Roles of the Barber Shop and Beauty Salon,” National Museum of African American History & Culture; Charles W. Singer military service and pension records, National Archives.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.