First in a multi-part series of Abraham Lincoln imagery by MI Contributing Editor Chris Nelson, featuring photographs from the author’s collection

Considering the world’s fascination with the government, economics and people of the United States—and the war that engulfed the nation—it is perhaps no surprise that the president drew international interest. In Europe especially, from where its laws and religion were imported and its population rooted, Abraham Lincoln loomed large. Countries long opposed to American slavery watched him closely. His words and deeds touched workers in places with their own social and economic tensions, post the 1848 unrest which sent so many immigrants to the U.S. Just consider the large number of politically progressive German regiments from New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Surviving cartes de visite of him credited to photographers outside the country are evidence of his place on the international stage. It is easy to imagine Lincoln’s likeness inserted into photograph album pages facing revolutionaries, royalty and rogues.

Like their American counterparts eager to satisfy the demand for images to fill albums, foreign photographers and distributors pirated and mass-produced portraits by or for Mathew Brady and his employee, then competitor, Alexander Gardner. Sometimes they replicated portraits directly. On other occasions, they adapted portraits, placing Lincoln’s head on another person’s body and other creative treatments, such as using a photograph for art reference to create a unique illustration.

During this era of evolving copyright law and enforcement in the U.S and abroad, enterprising photographers and commercial publishers across the U.S., Canada and major cities in Europe, especially London, Paris and Berlin, were not penalized for using original Brady and Gardner photographs. On both sides of the Atlantic, these pirated photographs produced from original albumen prints, known as second-generation copies, were generally of inferior quality.

Here we examine a representative sample of these images.

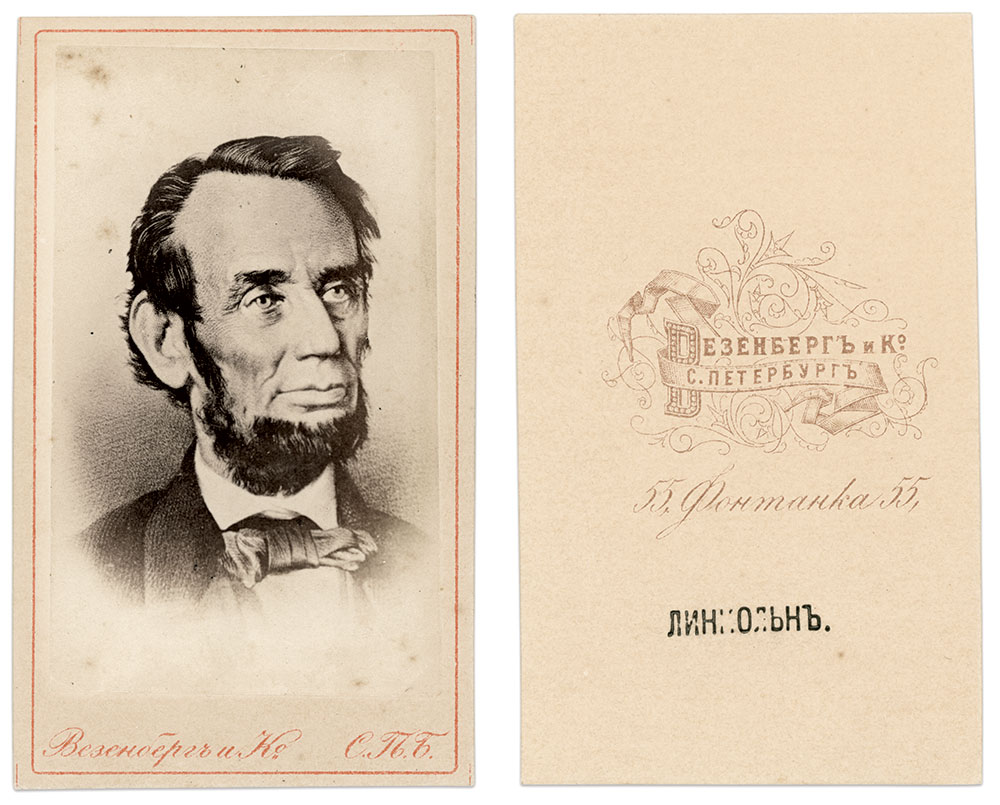

Russia

The well-known Saint Petersburg firm of Wesenberg & Co. pirated this illustration first published in the United States. A study of surviving American prints, including an example credited to The New York Photographic Co., suggests the Russians retouched the print that came into their possession. According to collector Sergey Maximishin, Wesenberg & Co. took advantage of loopholes in Russian copyright laws to pirate images during the late 19th century. Note the Cyrillic letters imprinted in black ink on the back of the mount—they spell “Lincoln.”

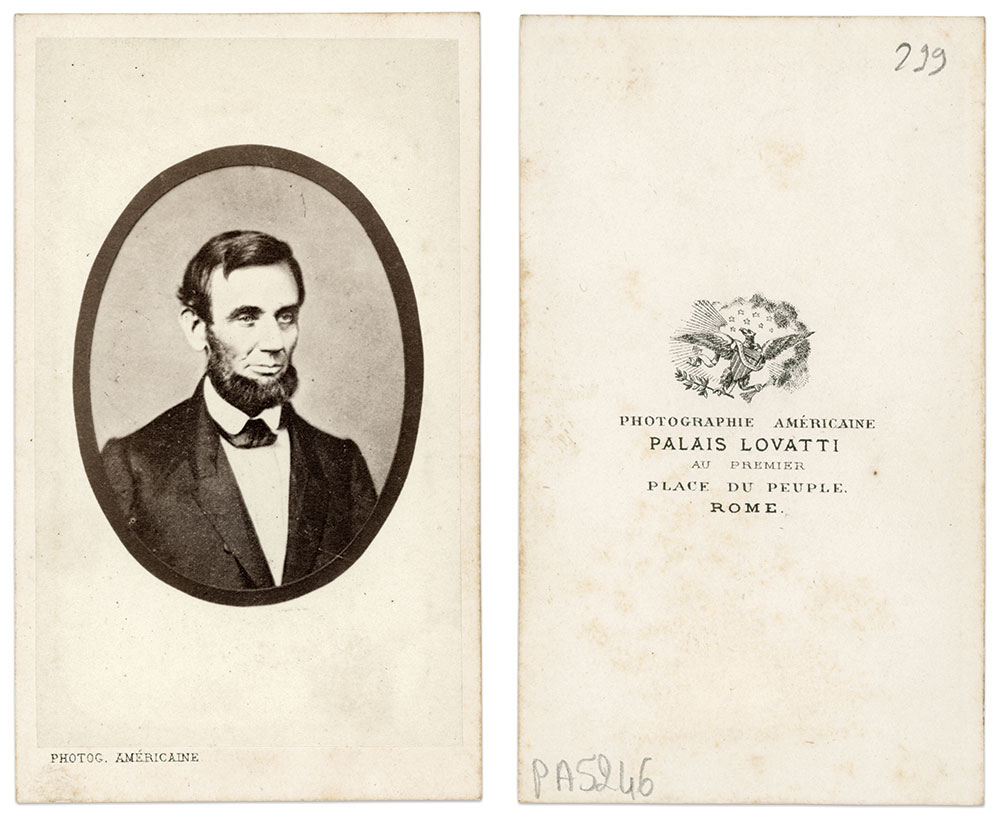

Italy

Visitors to Palais Lovatti’s Photographie Américaine gallery in Rome could purchase this carte de visite of Lincoln framed in a black mourning oval. The original traces back to an 1861 portrait by an unidentified photographer. American copies of this print are credited to Charles D. Fredricks & Co. of New York City, and Philadelphia photographers Washington Lafayette Germon and James Earle McClees. The best-known example is a large-format albumen print inscribed, “To my good friend, Mrs Fanny Speed. A Lincoln.” Fanny Henning Speed’s husband, Joshua Fry Speed, enjoyed a longtime friendship with the president.

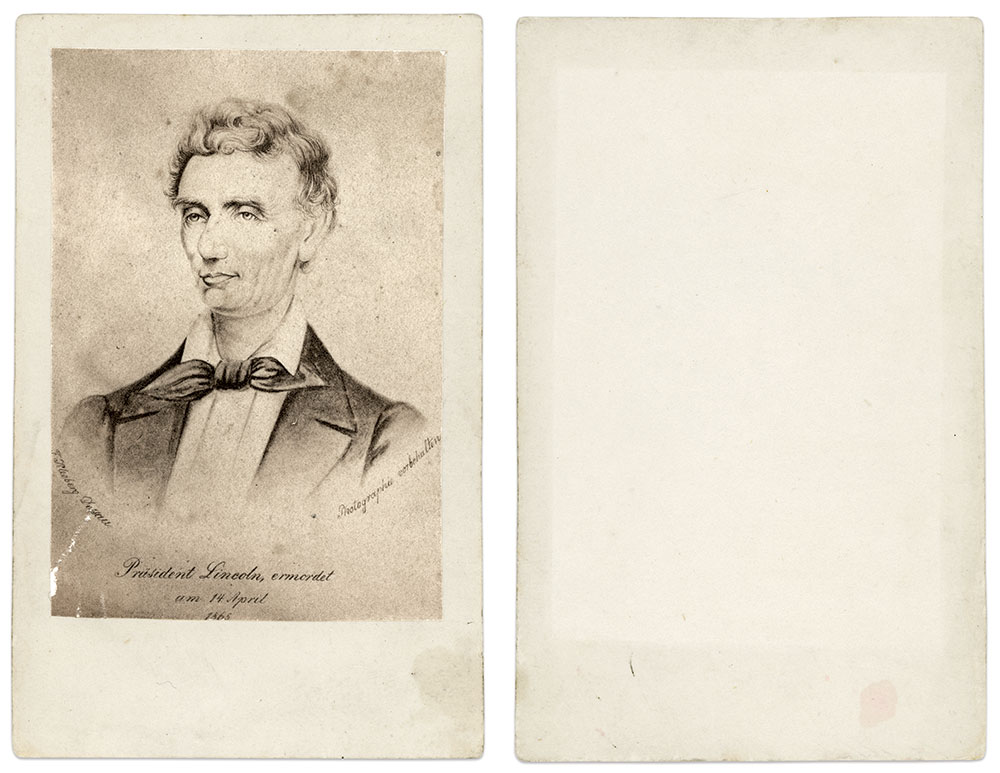

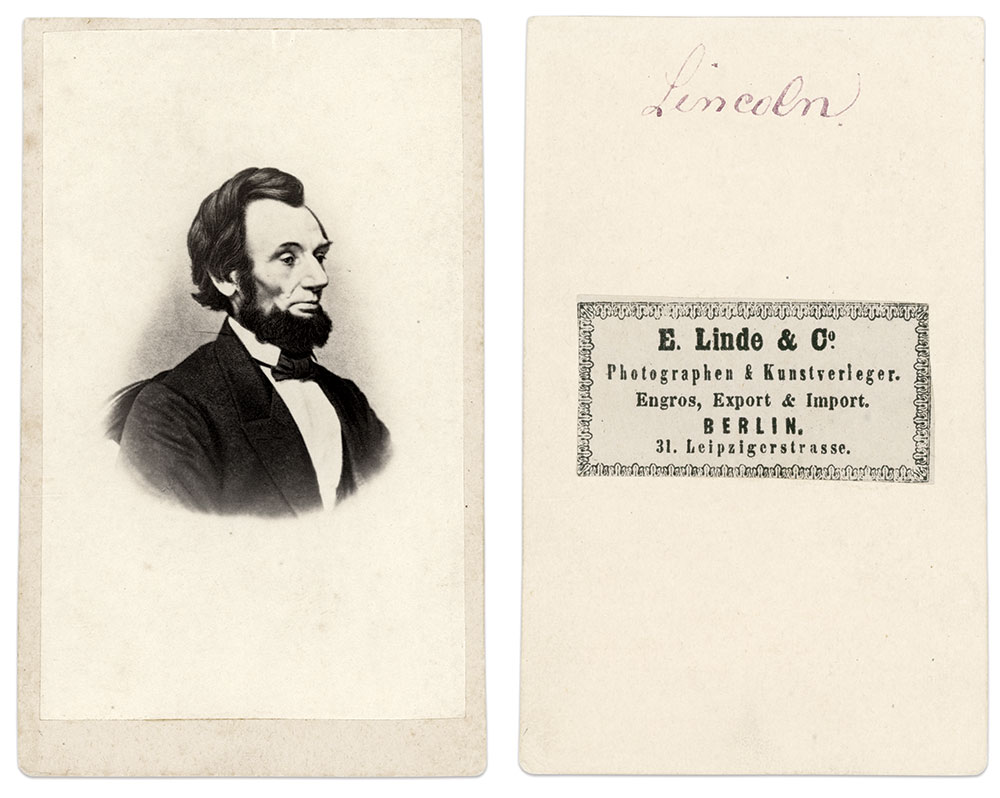

Germany

“Präsident Lincoln, ermordet am 14 April 1865,” or “President Lincoln, murdered,” is the title of this illustration likely inspired by Brady’s Cooper Union portrait. The individual credited along the oval margin is F. Kleeberg of Dessau. Present opposite this name is the phrase “Photographie vorbehalten,” or “Photograph reserved.”

In Berlin, Emanuel Linde & Co., mass producers of quality stereoviews and portraits from the 1860s into the 1880s, offered this pirated copy of one of three likenesses of a seated Lincoln taken after his 1861 inauguration. His swollen right hand, a casualty of countless handshakes, is not visible.

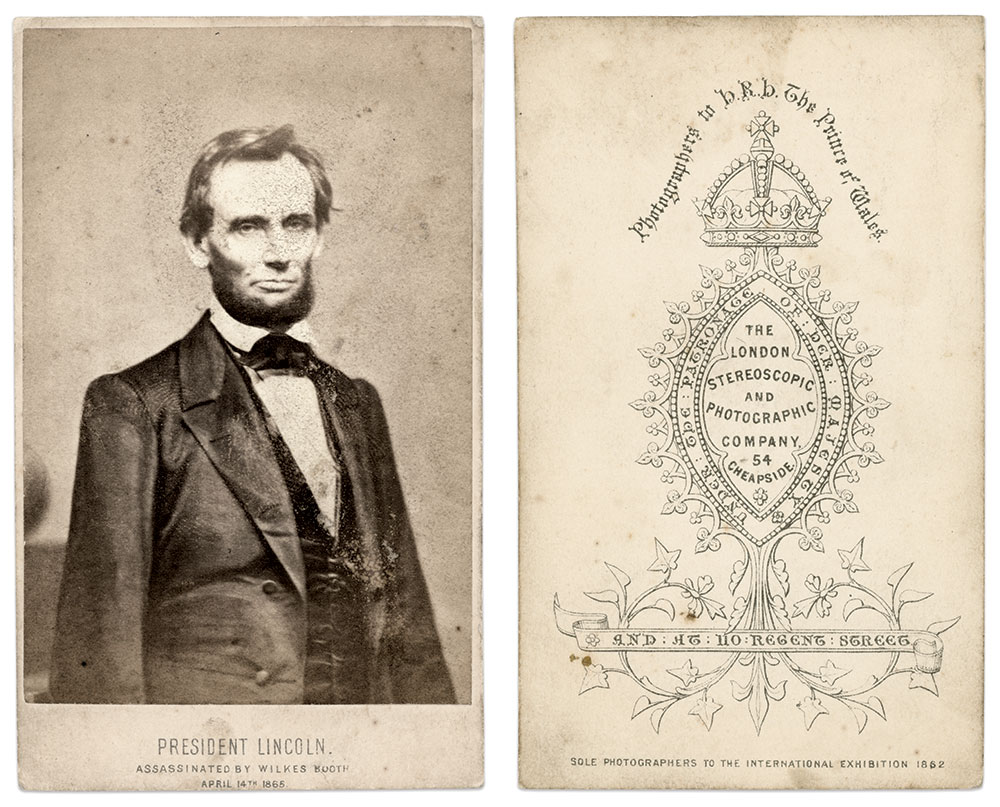

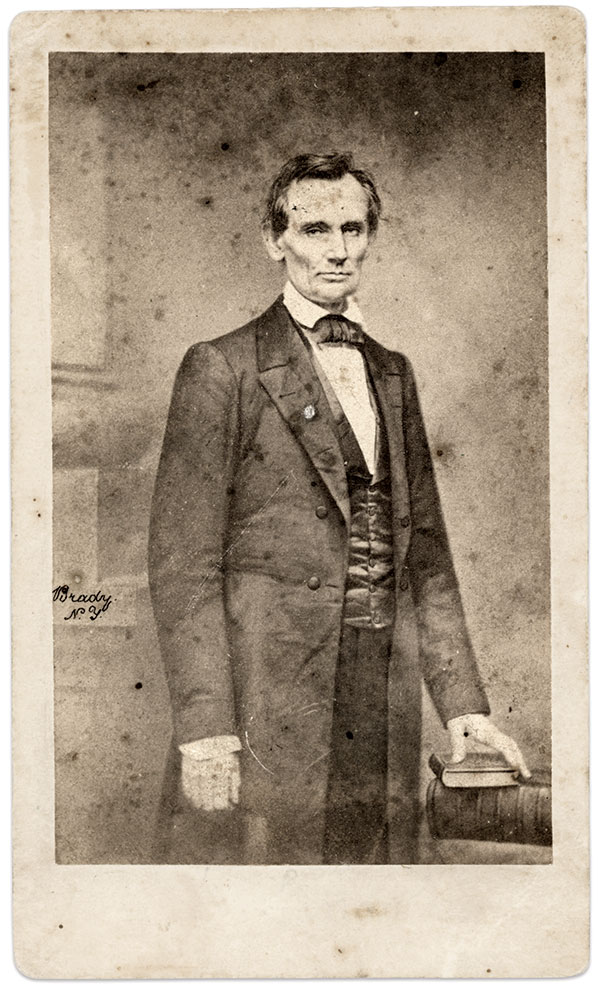

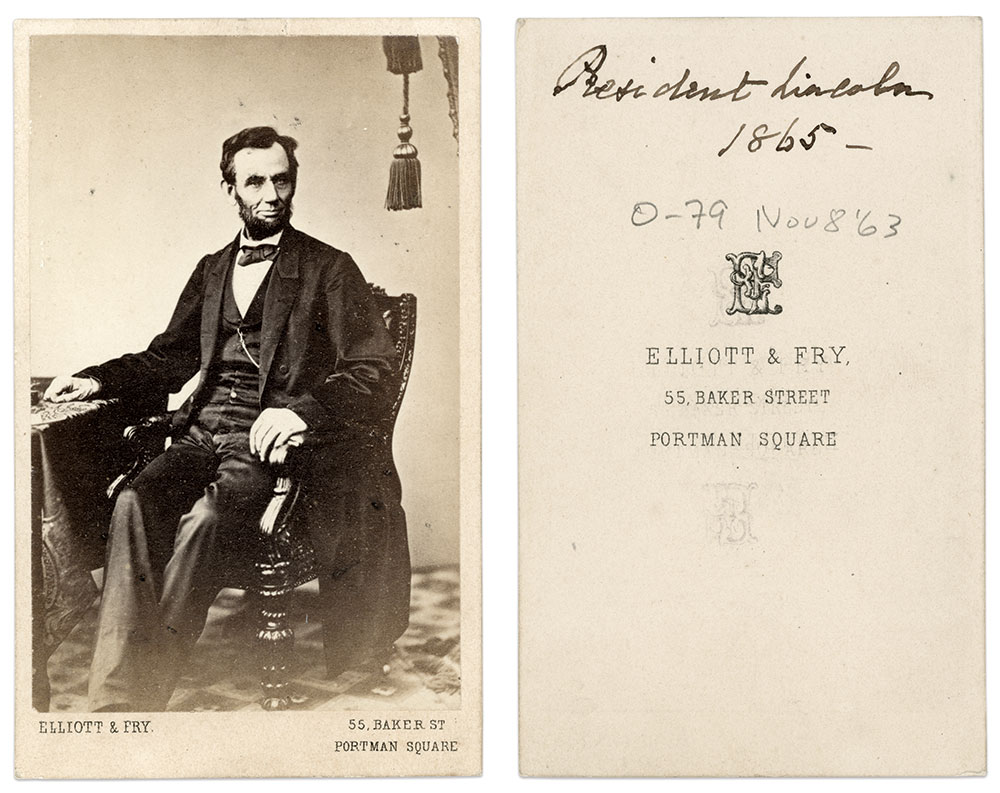

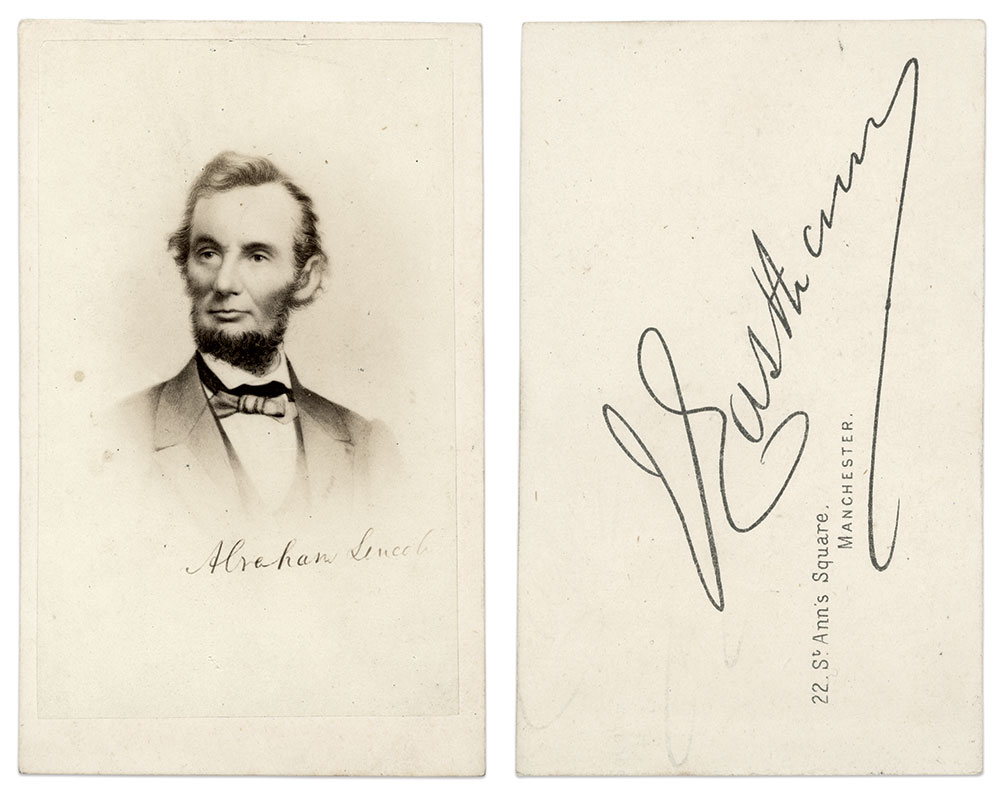

England

The London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company produced this image following Lincoln’s assassination. By this time, the Londoners might have pirated any number of presidential portraits. They made a notable choice: The 1860 Cooper Union photograph, to which has been added a convincing beard.

Three miles east of The London Stereoscopic’s 54 Cheapside address, photographers Jasper John Elliott and Clarence Edmund Fry on 55 Baker Street opted for a portrait of Lincoln with an authentic beard. The president sat for this likeness in the Washington, D.C., studio of Scotsman Alexander Gardner on Nov. 8, 1863. Less than two weeks later, Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address. The back of the mount of this carte is inscribed “President Lincoln 1865.”

Meanwhile in Manchester, the John Eastham gallery offered this heavily retouched portrait that appears more illustration than photograph. Lincoln, his wrinkles largely removed and mouth somewhat stylized, gazes above the lens of the camera and off into the distance—a positive portrait of the “Savior of the Union” and the “Great Emancipator.”

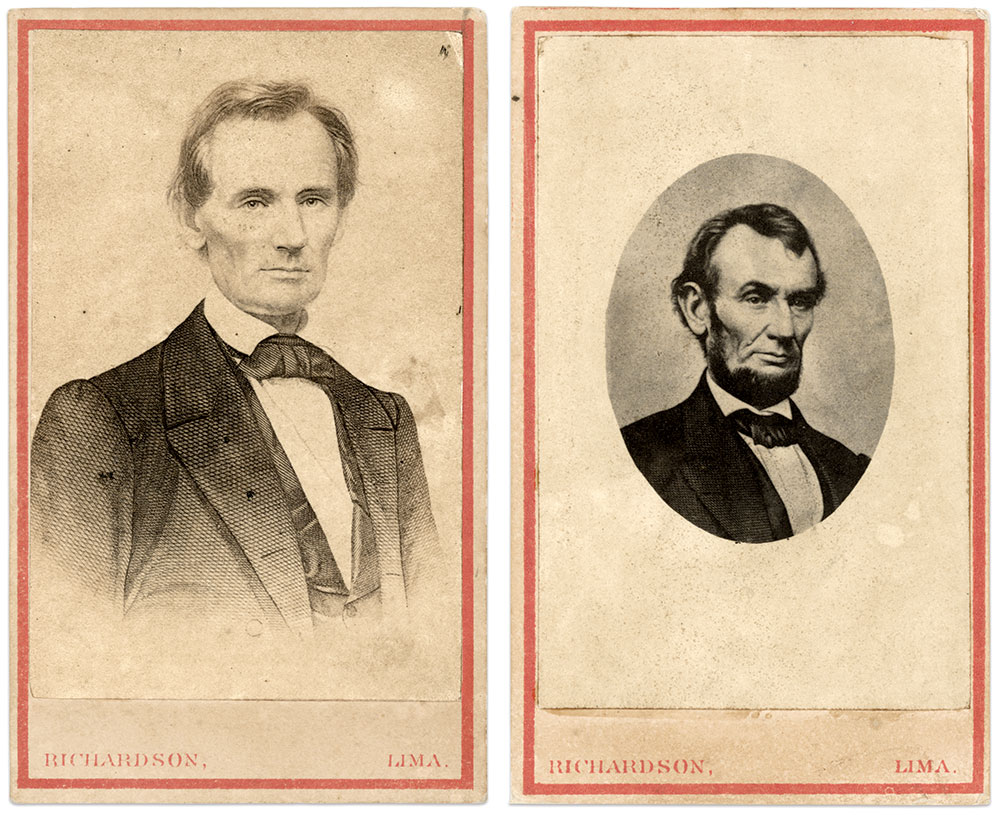

Peru

American born photographer Villroy L. Richardson copied this print of a beardless Lincoln not from Brady’s Cooper Union likeness, but from the 1860 campaign biography Life and Speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin. The other example here also appears to be copied from an engraving, as evidenced by the telltale crosshatching on his frock coat.

Richardson established his Photographica Americana gallery in Lima, Peru, in 1862. The single, thick red rule on the carte de visite mount is typical for his wartime images. Considering the photomontage caricatures that he produced in the 1860s of politician heads on the bodies of animals, which caused him problems with the Peruvian government, these Lincoln portraits seem rather tame.

France

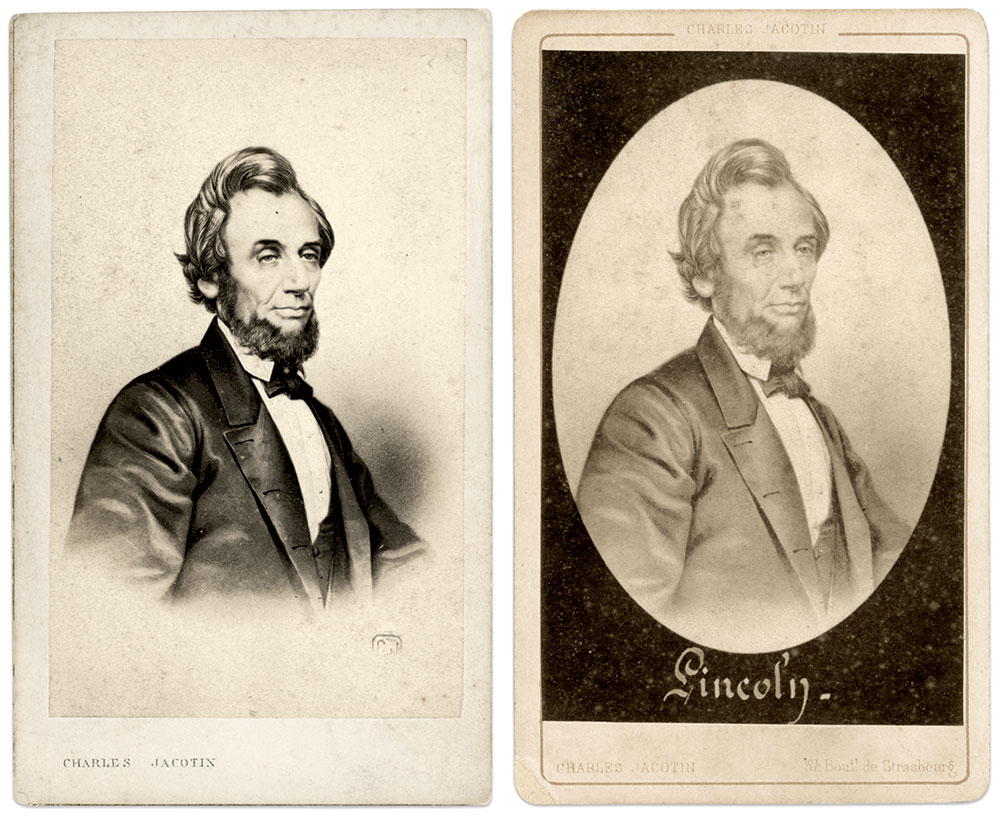

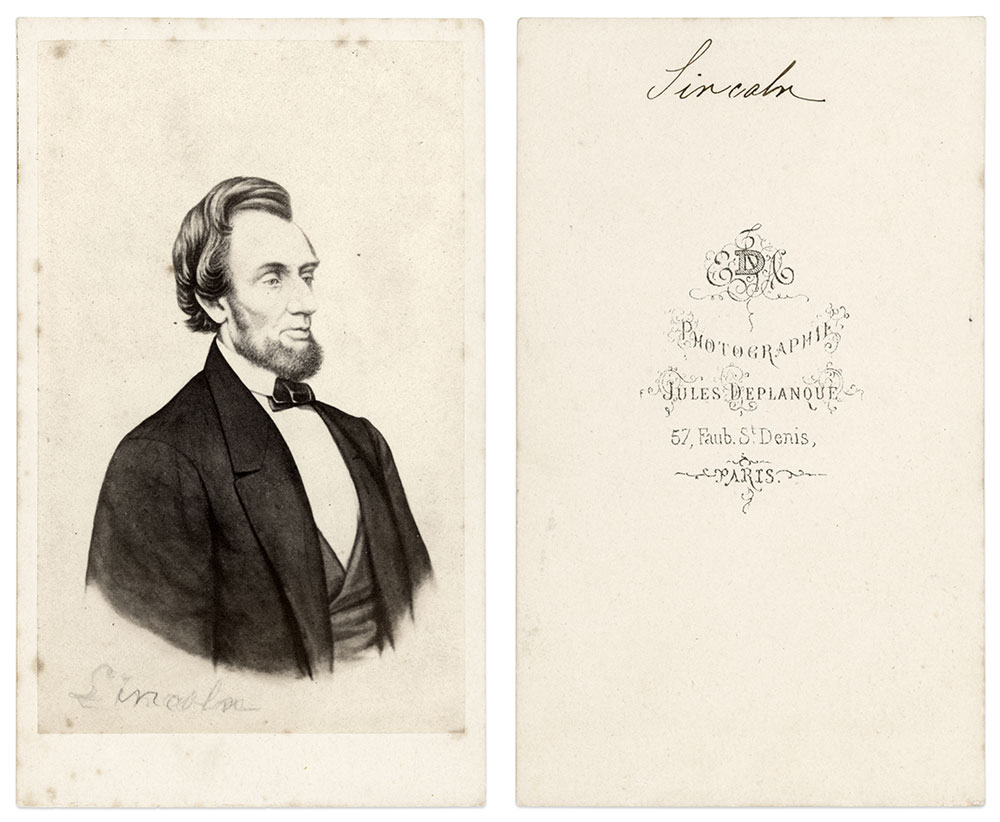

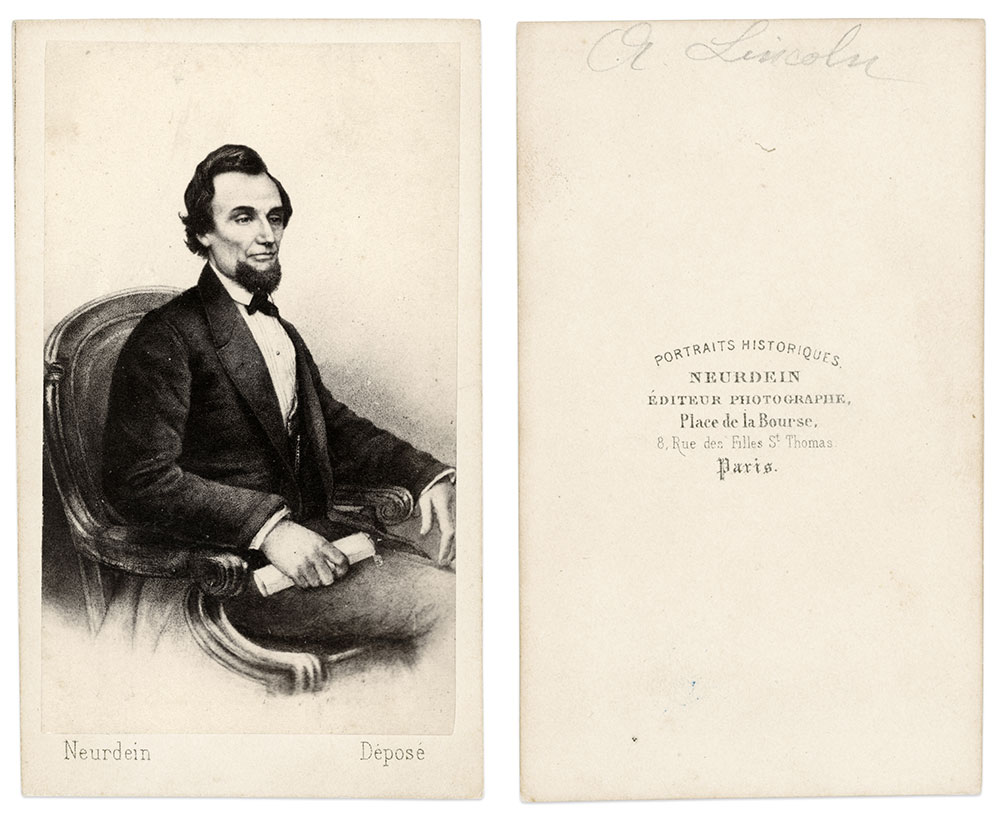

Brady’s 1861 portrait variants

In 1861, Lincoln again sat for Brady, and the resulting portrait circulated as much as the Cooper Union image had only a year earlier. Though these three versions by Parisian photographers differ from the Brady original, all consistently depict Lincoln’s face at a three-quarter angle and with long hair and beard.

Charles Jacotin, who became active about 1863, published this heavily retouched portrait of the American president, minus the chair visible in Brady’s original. In 1884, Jacotin republished the image, this time inside a dark oval, as part of a series of notable gentlemen and ladies.

Photographer Jules Deplanque’s Lincoln appears to be an illustration in ink and watercolor or gouache based on Brady’s portrait, or perhaps the engraving of the portrait published in Harper’s Weekly. He sits upright rather than leaning forward, and the chair is missing.

A chair is visible—though of a different style—in this illustrated portrait published by Étienne Neurdein of Paris. Lincoln’s likeness was part of a circa 1864-1865 series titled “Portraits Historiques” that included Napoleon, Joan of Arc, King Charles VII, and others.

Beardless variations

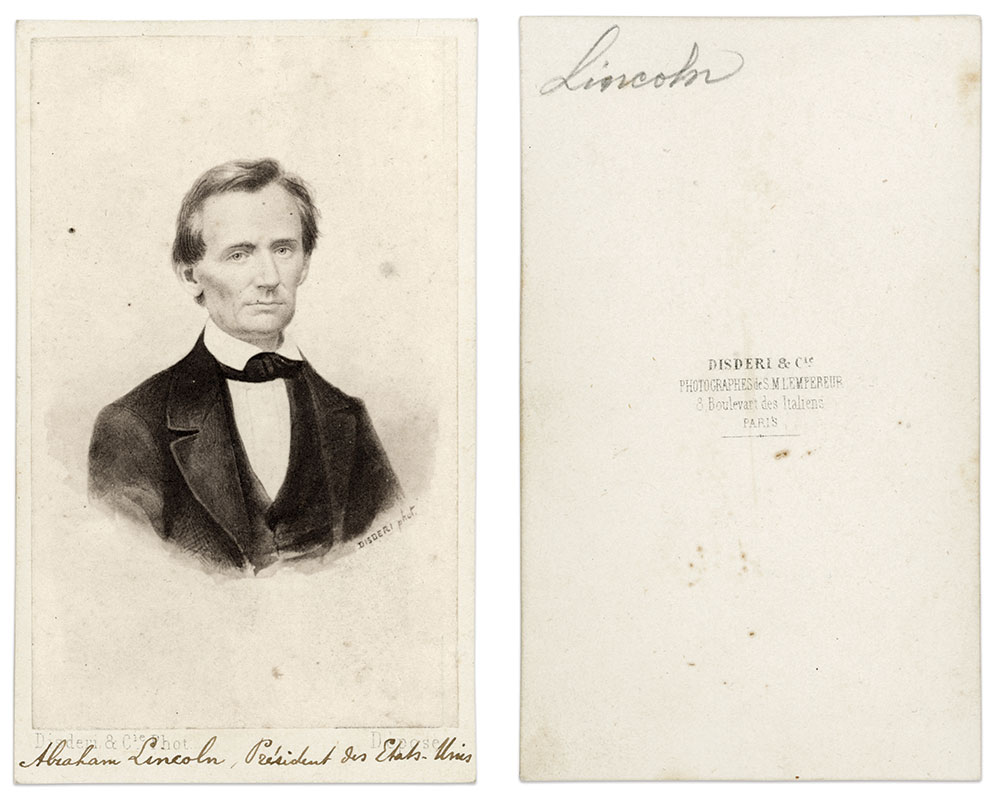

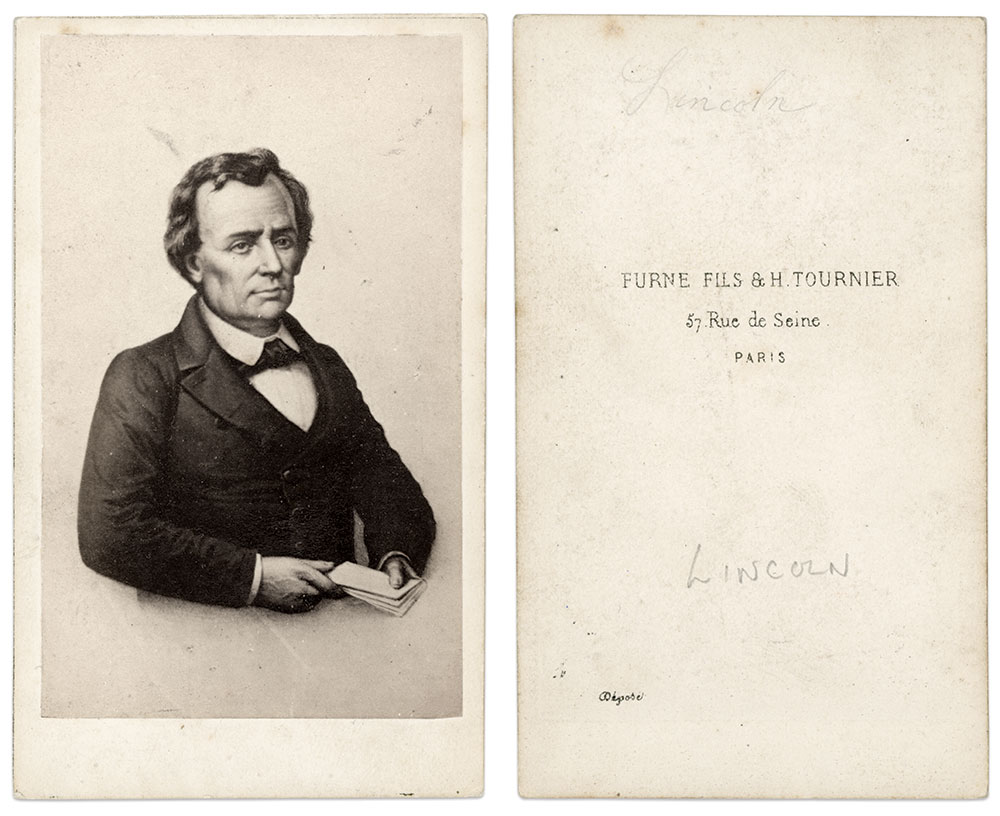

Two Parisian photographers offered versions of the beardless Lincoln.

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri’s portrait is somewhat modified from the Brady original. Lincoln’s features are softer, especially his brow, cheekbones and lower lip. His bowtie is neater and his vest and lapel less angled. Disdéri is best known for patenting the carte de visite camera and launching the Cardomania craze that swept Europe and the U.S. in the early 1860s.

Photographers Furne Sons and Henri Tournier’s Lincoln appears to be based on the iconic portrait by Brady of Lincoln during his February 1860 visit to New York City to speak at the Cooper Institute (today’s Cooper Union). The portrait was widely printed and featured as engravings in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. However, it is significantly altered from the original. Lincoln’s face is fuller, his ears smaller, forehead wider and hair wavy. His body is chunkier than Lincoln’s lanky frame. He holds a folded paper in hand, perhaps a nod to his abilities as a speechmaker. The team of Furne Sons and Tournier were active from the 1850s until 1862.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.