By Kurt Luther

One of the most remarkable attributes of the Civil War photo sleuthing community is the willingness of its members to help one another. In a previous column (Winter 2020), I interviewed experienced photo sleuths about their motivations for sharing photos with the broader community. Paramount among these motivations was helping other people, including fellow collectors, historians and descendants. Beyond photos, community members share many other types of valuable information, including advice and tips, reference materials like books and articles, details about specific soldiers and units, and opinions and feedback on potential identifications.

Several years ago, we launched the Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) website, which uses crowdsourcing and face recognition to help users identify unknown Civil War photos. The site now has more than 15,000 registered users and more than 40,000 photos of Civil War-era soldiers and civilians. Despite this growing community, using CWPS has thus far been largely an individual experience, with limited support for collaboration or discussion.

Over the past year, the CWPS team has developed several new features that focus on collaboration and community, allowing users to discuss photos and identifications, request and receive help, and share information and opinions. In this column, I introduce one of these features, “SleuthTalk,” which lets users request feedback on potential identifications of unknown photos, while maintaining control over their information.

From Second Opinion to SleuthTalk

In the Summer 2019 issue of MI, we introduced Second Opinion, a new Civil War Photo Sleuth feature that allowed users to request feedback from other people on potential soldier photo identifications. Second Opinion was designed to help with what we call the “last mile” problem, where CWPS’s face recognition technology narrowed down possible matches for an unknown photo to a small number of highly similar candidates, but deciding among this shortlist is difficult. Consequently, Second Opinion let users request a “crowd” of human workers to systematically analyze the facial features of each shortlist candidate for similarities and differences.

Users told us that Second Opinion helped them build confidence in their identification decisions and notice key details they might have otherwise missed. However, the tool had some limitations. Users wanted to be able to invite trusted friends and colleagues, not just strangers, to weigh in on potential matches. They also wanted more control over which photos comprised the shortlist, rather than being limited to face recognition’s top five picks.

Projects, privacy and polls

In response, we spent a year redesigning Second Opinion to give users more control over the process of asking for feedback on potential matches. These efforts, led by Virginia Tech graduate students Liling Yuan and Vikram Mohanty, resulted in a new system called SleuthTalk.

SleuthTalk re-conceives the feedback-seeking process more broadly as a “project.” First, a user uploads an unknown photo and applies visual tags and search filters. (This part of the identification process is unchanged.) Next, the user reviews the search results, sorted by facial similarity, and clicks a button on promising matches to add them to a “shortlist.” This shortlist forms a “project” led by that user.

A user can invite up to nine people to a project. Project members can be trusted colleagues, friends, family or anyone else. If the user wants to invite someone to the project who doesn’t yet have a free CWPS account, the user can simply provide that person’s email address and they will receive an email with instructions and an invitation link to join the project.

Projects are only visible to the project creator and invited members. This privacy helps the user control not only who is let into a project, but also what information is allowed out. Misidentifications are a growing problem in photo sleuthing, and once a false ID is posted online, it becomes almost impossible to get rid of it. Private projects with trusted members provide a closed environment where members can propose (and debunk) a wide range of possible identities with greatly reduced risk of wrong information leaking out.

Within a project, members analyze each shortlist candidate in detail. New tools allow members to highlight and label features in each photo that reveal important similarities and differences. A threaded discussion forum within the project allows members to converse directly with one another, and pull in outside information like military records and additional photos. New shortlist candidates can be added if the investigation takes a different turn, and candidates no longer under consideration can be hidden. Members can vote on the similarity of each candidate to the unknown photo, as well as participate in an overall poll for which candidate (if any) possesses the correct identity. If there is consensus, the identification becomes public on CWPS and the project members are credited.

Real-world testing and release

We ran a study with six CWPS users to evaluate the usefulness of SleuthTalk. They created nine projects and sent 45 invitations, including both existing CWPS users and new ones. They added 37 candidates from shortlists, highlighted 254 similarities and differences in facial features, and cast 125 votes on potential matches.

In interviews, study participants told us they saw SleuthTalk as complementing, rather than replacing, the ways they use social media for photo sleuthing. They imagined first posting an unknown photo in a Facebook group to request information and proposed identifications from the public. These requests would often attract dozens of replies of varying quality. Then they would take the most promising suggestions into CWPS and create a SleuthTalk project for closer inspection and debate with members they trust.

Participants also told us about how feedback from trusted members changed their perspectives on potential IDs. In one project, the creator cast a positive vote for a candidate, while other members gave it three negative and two “not sure” votes. These differing opinions led the creator to do more research on the candidate, and discover additional reference photos when the soldier was younger and lacked facial hair. Returning to the project, he posted in the discussion that “after thoroughly comparing all candidates to my image, I have come to the conclusion that none of them is my officer.” Diverse opinions offer a powerful antidote to confirmation bias.

After making some improvements based on feedback from the study, we publicly launched SleuthTalk in June 2021, and it is now available on CWPS. New projects can be created following the steps above. You can view your active and completed projects, and any invitations to other users’ projects, by clicking the “Your Projects” button on the dashboard after logging in. Even if you are not seeking second opinions, projects can be useful for privately organizing your own individual investigations, and the option to invite others is always left open.

Next steps

SleuthTalk is just one of several features we have released to improve community and collaboration on CWPS. Look for others in future installments of this column. Meanwhile, I encourage you to create your first SleuthTalk project (it’s free!), and invite a few trusted friends and family members. Civil War photo sleuthing works best when we work together.

Talking SleuthTalk

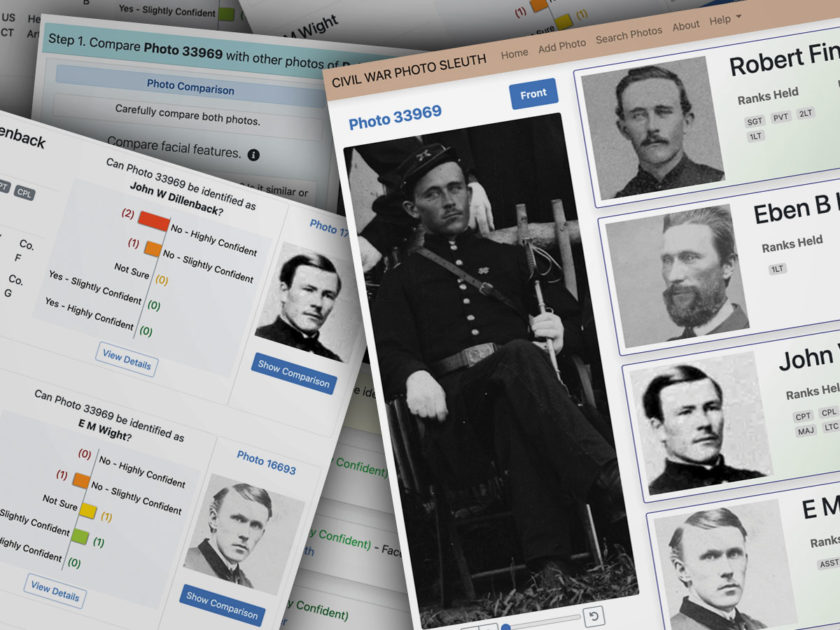

This example illustrates how members of the Civil War Photo Sleuth community can collaborate and communicate to comment on different aspects of photographs.

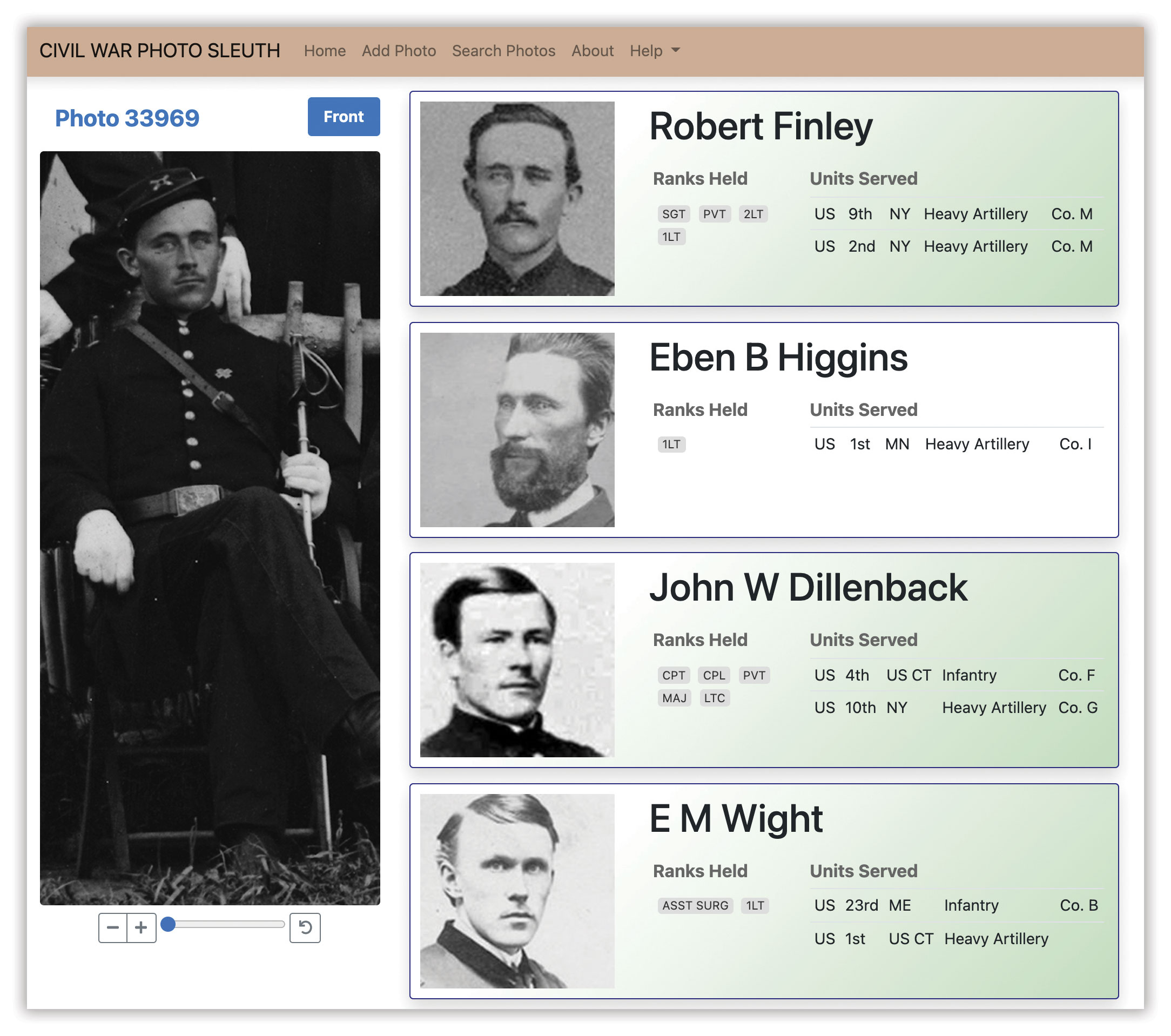

STEP 1: Build Shortlist and Create Project

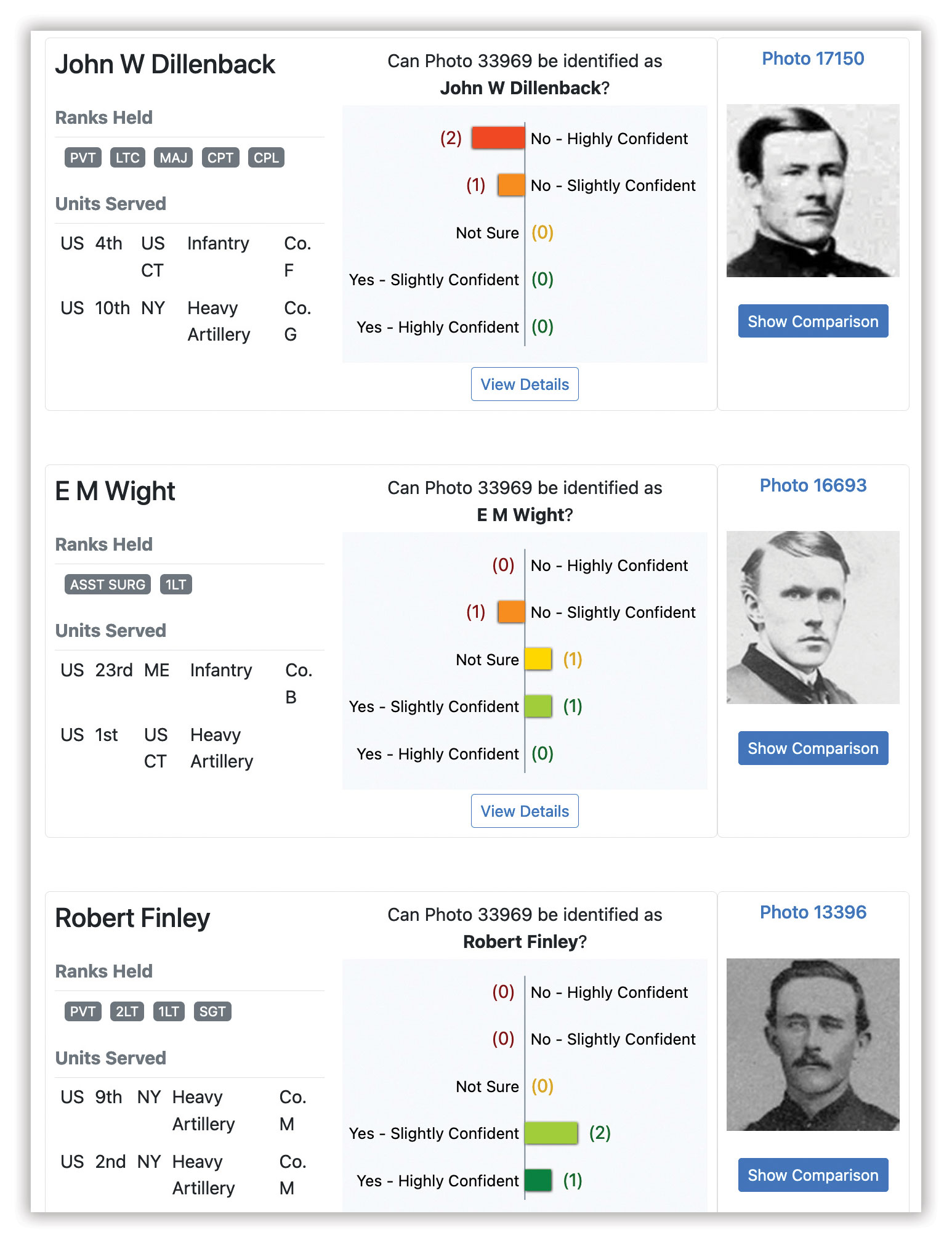

After uploading my mystery photo (33969) and running a search, I review the facial recognition results. I add three promising candidates to my shortlist—Finley, Dillenback and Wight—represented by green backgrounds.

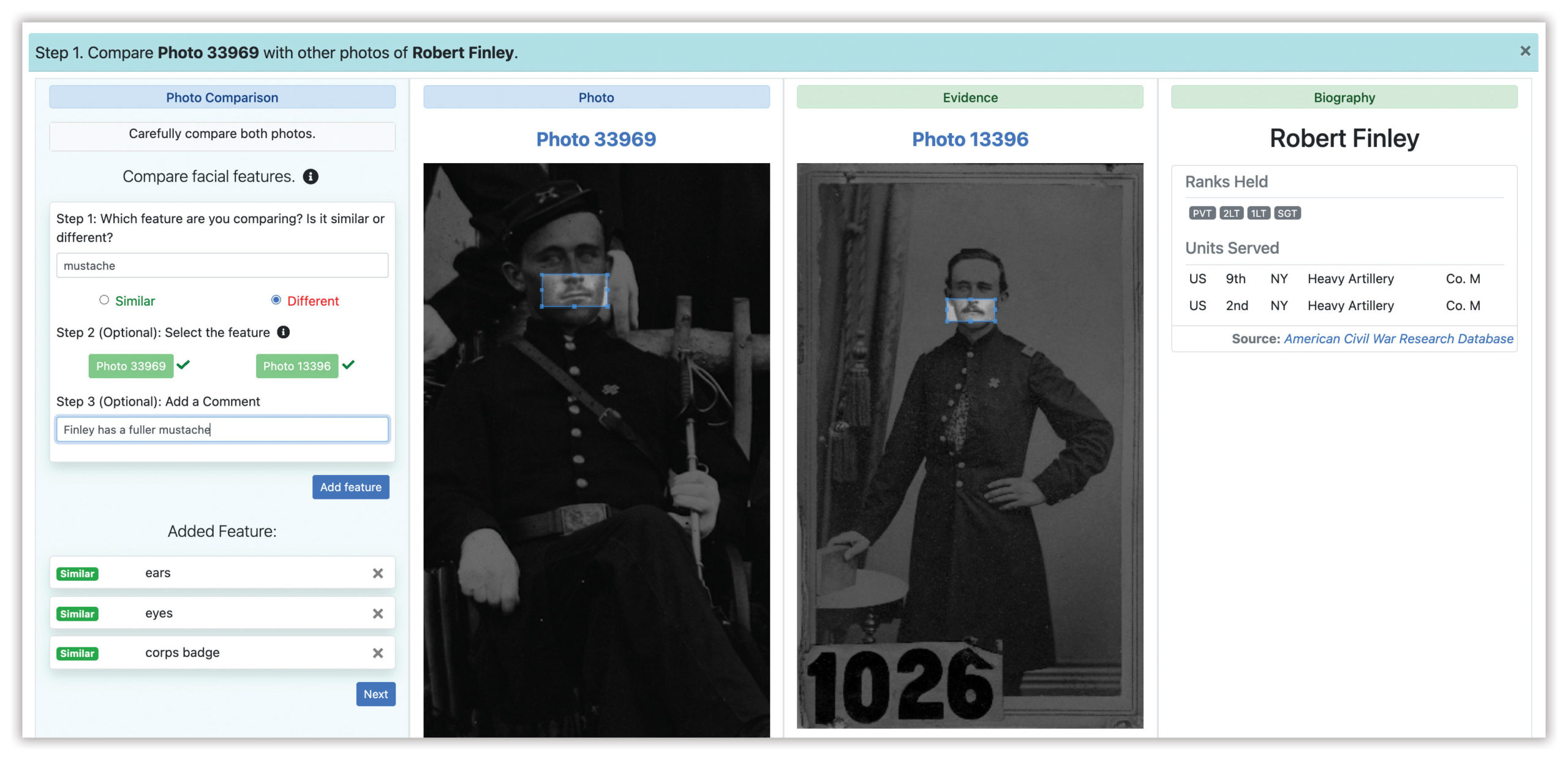

STEP 2: Invite Members and Compare Candidates

Next, I invite two trusted friends, Alice and James, to the private project. All project members compare each candidate to the mystery photo and highlight key similarities and differences. Here, the candidate Robert Finley has similar ears, eyes and corps badge, but a different mustache.

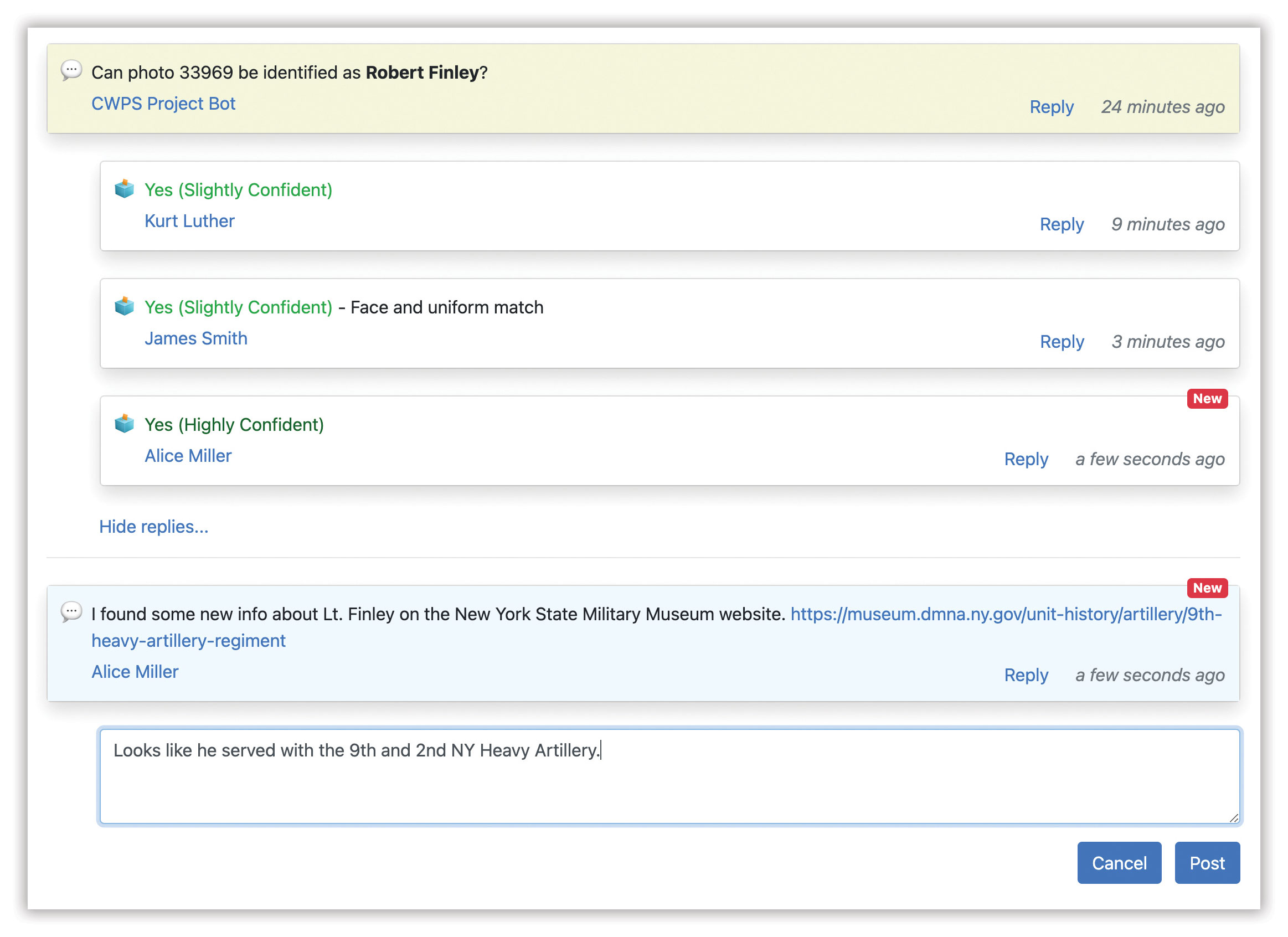

STEP 3: Discuss Candidates and Share Information

Each project has a threaded discussion forum where project members can post comments and replies to debate the shortlisted candidates. Here, I am replying to a link posted by Alice with military records related to Robert Finley.

STEP 4: Review Votes and Finalize Decision

The project members’ votes for each candidate are visualized as a bar chart. Here, Robert Finley emerges as the most promising candidate, with three “yes” votes. As the project creator, I can hold a final vote on Finley, and if the project members agree, his identity will be publicly linked to the mystery photo.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.