By Ronald S. Coddington

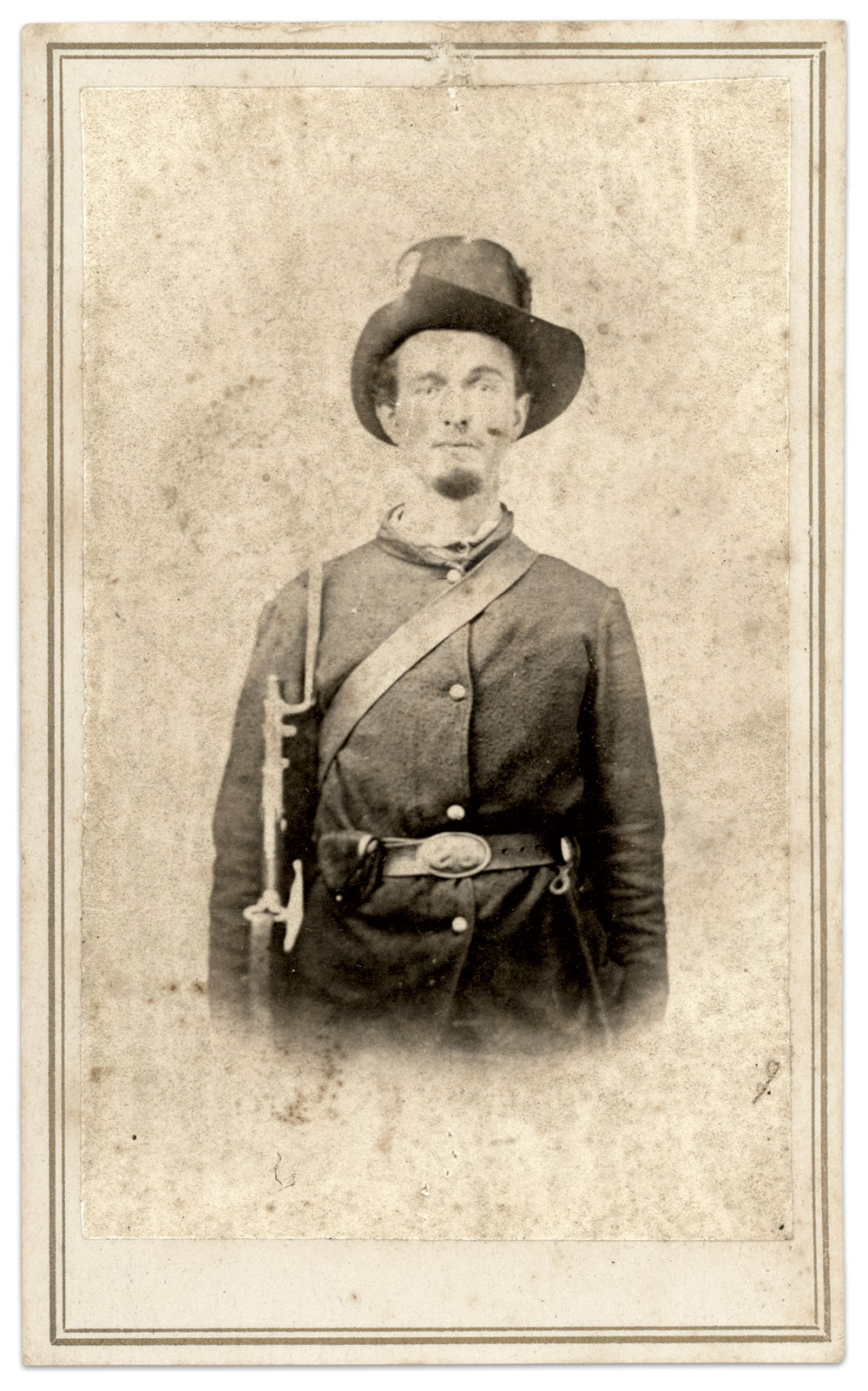

Corporal Sylvester Leaming drifted in and out of consciousness from his hospital bed in Nashville on a June day in 1864. Wasting away from disease and disfigured by a stump of flesh in place of his left foot, medical staff believed he had little time left.

His nurse, Sallie Dysart, found him in this condition on Sunday, June 12. She arrived at his bedside and learned from the boy lying in the next cot that Leaming had been talking about her in his delirious state. He also mentioned that Leaming had received a letter.

Their voices roused Leaming from the fog that clouded his brain. Sallie offered to read the letter to him, and he accepted. She read it aloud several times. Leaming’s periodic bouts of coughing interrupted the soothing words from home. He urged her on by speaking softly and politely “go on,” and, finally, “a sweet, good letter.”

Sallie paused. The letter had been a tonic for her patient. After a silent calculation, she eased into a difficult conversation—preparing him for death. “Oh, Mr. Leaming, I am afraid you will never go home to your friends.”

A skeptical Leaming said he hoped he would. Sallie, more direct now, revealed that the doctor had told her he could not fight the disease much longer. His body had grown too weak.

Leaming, still disbelieving, replied, “Did he!”

He did.

A Wagonmaker goes to war

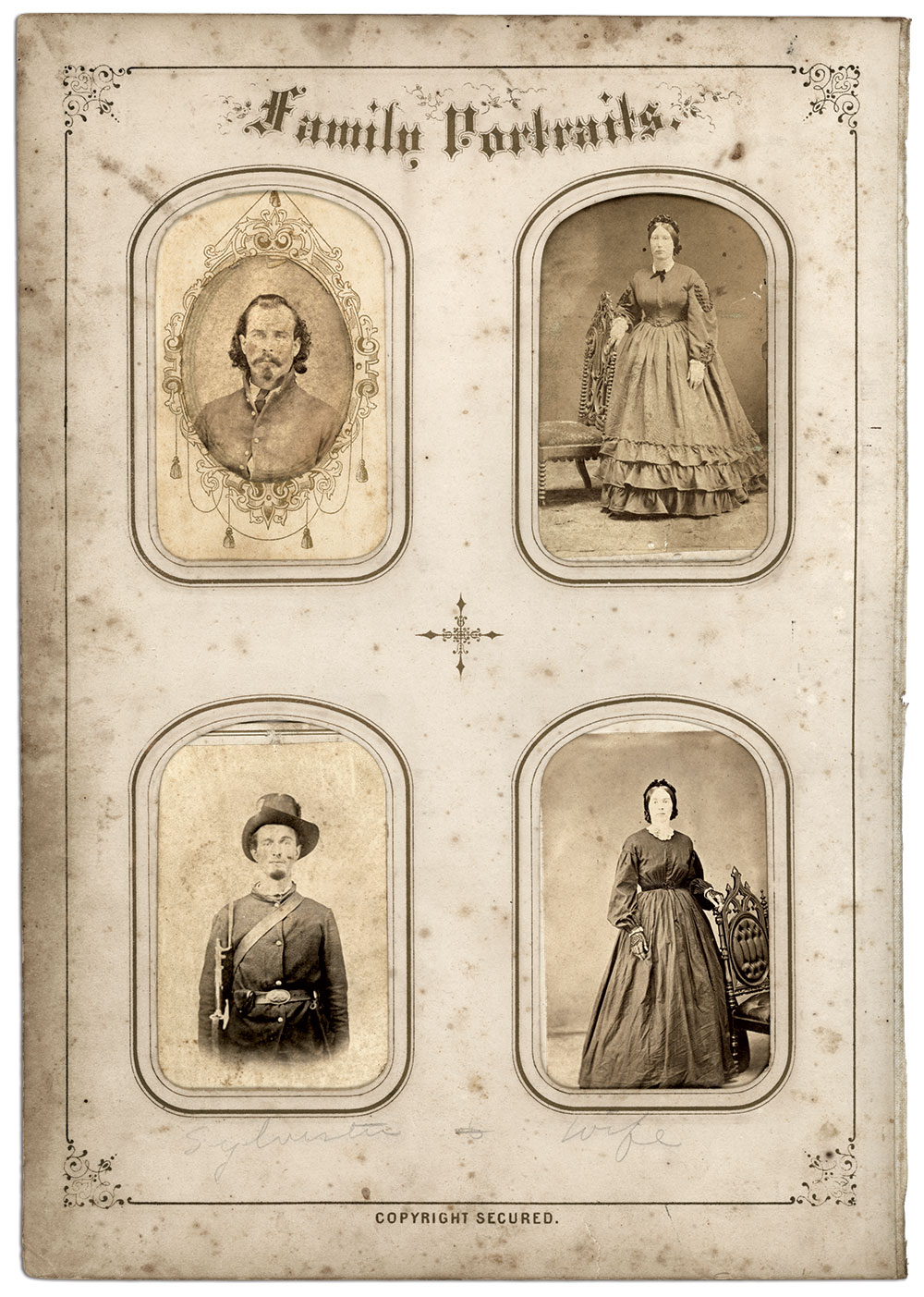

Four summers earlier and 350 miles due north in the Indiana county of Tippecanoe, Leaming and his newlywed wife, Melinda Dodson, stood at the threshold of a promising life in Sheffield Township. Sylvester, 21, worked as wagonmaker. Melinda, 18, carried their first child.

Months later, on Jan. 2, 1861, the couple welcomed baby Frank into a country in crisis. In the wake of the election of Abraham Lincoln of neighboring Illinois as the nation’s 16th President, South Carolina renounced its allegiance to the Union. During little Frank’s first weeks more Southern states seceded, took possession of U.S. arsenals, and formed a government.

The bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861 prompted a flood of army enlistments on both sides. Hoosier State boys volunteered to defend the Constitution during the days and weeks following the surrender of Sumter’s beleaguered garrison. Leaming did not join the army immediately—with a newborn son and young wife, and a general belief that whatever war laid ahead would be a short and decisive Union victory, it is easy to imagine why he did not go.

Then came Bull Run, and with it the realization that this war would not end soon. In October 1861, Leaming responded to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers to put down the rebellion. He joined the 40th Indiana Infantry, a new regiment organized in Lafayette, the county seat, and became a corporal in Company A.

Leaming left Melinda, now pregnant with their second child, and baby Frank to become a soldier. His parents, George and Juliette, and siblings lived in the area and could look after his young family. Leaming followed in the footsteps of his younger brother, Clay, who enlisted in the 17th Indiana Infantry a few months earlier. Leaming’s older brother, Cyrus, joined the 5th Indiana Cavalry in 1862. Melinda’s family also contributed a soldier to the war. Her older brother, Jacob, joined the 111th Indiana Infantry in 1863. In addition, Sylvester was not the only Leaming in the 40th. His first cousin, Henry, a resident of nearby Romney, served as a captain of Company C.

Leaming and his comrades left home in early 1862 and transformed from citizen soldiers to battle-hardened veterans at Shiloh, Perryville, and Stones River. During the fighting along Stones River outside Murfreesboro, Tenn., the Hoosiers faced a crisis of command when their colonel, John W. Blake, turned up drunk and was relieved from duty. Blake’s second-in command, Lt. Col. Elias Neff, led the regiment until he suffered a disabling wound. The next officer in line, Leaming’s cousin Henry, now major, took charge for the rest of the engagement.

Maj. Leaming’s after-action report paid tribute to his command: “The conduct of the regiment under the most trying circumstances was worthy of all praise. The coolness and quiet determination of officers and men were admirable, and not less so the cheerfulness of sprit with which the hardships and exposure to cold and rain were borne. The regiment did its duty faithfully. I know no higher praise that can be given it.”

The casualty list included about 85 officers and men, including Leaming, who suffered a severe leg wound. Details of the injury and length of time he spent in treatment and recovery are not precisely known.

Fighting for “sacred rights” along Missionary Ridge

Back home in Sheffield Township, death visited Leaming’s family. His second child, a son named for him, died in the middle of 1862, about two weeks after Melinda brought him into the world. Little Frank joined his infant brother in death during the spring of 1863.

Leaming’s Stones River wound had healed by November 1863, and he had returned to active duty. His regiment and the rest of the Union Army of the Cumberland had suffered a stunning loss at the Battle of Chickamauga in September and now occupied a precarious position—effectively surrounded by Confederates at Chattanooga, Tenn.

On November 18, Leaming wrote to his parents, “The news here is about like it has been for a long time, both armies laying face to face watching each other closely. I came off picket this morning. Our pickets and the Rebs is about two or three hundred yards apart where picketed but neither party is allowed to fire unless the other advances.”

He continued, noting the service of his brothers, “Father indeed your representation in our noble Army is very large now even the last boy capable of bearing arms has given himself to his country’s cause, may you both live to see your country free once more and if it is the Will of God to welcome your file of soldier boys home at the end of the struggle is what I ask, then you will be amply paid for your anxiety in behalf of justice and right and the welfare of a great Nation.”

He also added, “It is to be hoped that all things will work out for our good and the good of the government. All that it left for us to do is to do our duty as soldiers fighting for what we believe to be our sacred rights.”

Leaming had good reason for optimism. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had recently arrived and took charge of the army, opened a supply line, and prepared for an offensive.

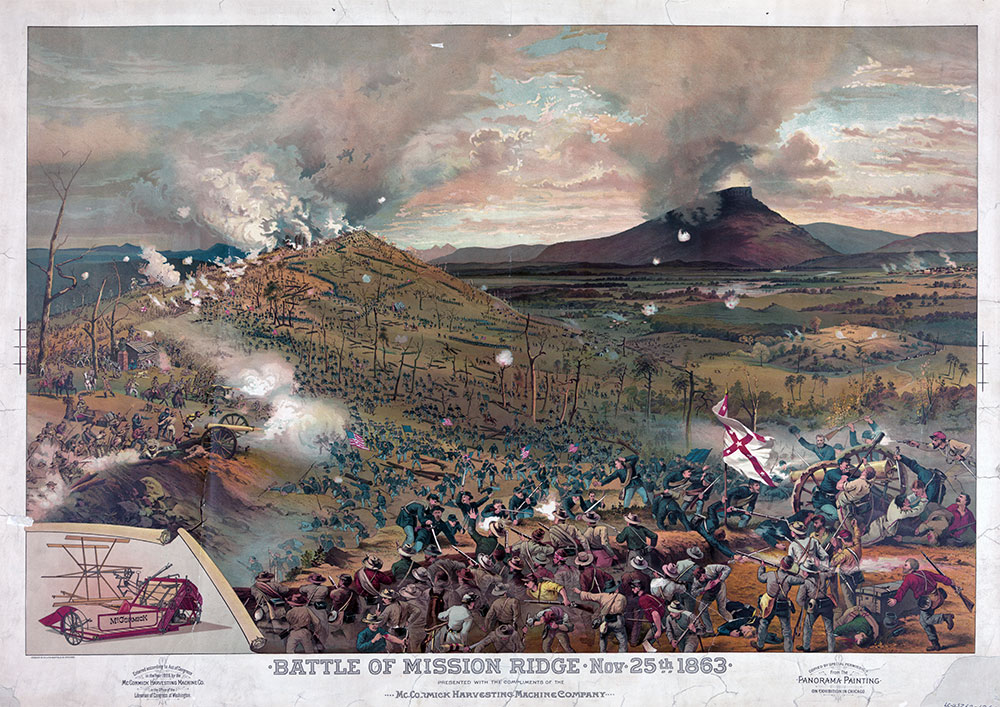

Exactly a week after Leaming’s letter, on November 25, the Union army launched an all-out assault against its besiegers along Missionary Ridge. Maj. Leaming offered this perspective of that awful and glorious day, “Stones River was a skirmish, as far as our regiment was concerned, to this affair.”

Events unfolded early that afternoon, when the 350-strong 40th and its brother regiments started off on a mile-long trek in sections. With hearts beating quickly and adrenaline pumping the men made the first quarter mile before halting to dress the lines. The second quarter mile began with a brisk walk up to a cover of thickets before breaking into a full run and occupying the enemy’s rifle pits. In the rush, some of the Hoosiers overshot the mark and kept on going. Lt. Col. Neff recalled these men, admitting it was difficult to restrain them in the moment. The overzealous soldiers did not have long to wait. Orders soon came to advance another quarter mile—a full-on sprint to the foot of Missionary Ridge through a storm of hot lead spewing from cannon tubes and musket barrels. Losses up to this point were miraculously small.

Here, the Hoosiers took cover as best they could. Maj. Leaming, 38 years old this day, paused to catch his breath from running after losing his horse at about the halfway point. Lt. Col. Neff huddled with an aide relaying orders from his brigade commander. Company officers prepped the ranks and braced for the final mad dash up the ridge into the epicenter of fire.

Finally, the order to climb the ridge arrived and the men departed. No sooner had the movement got underway than all were called back to the rifle pits. Scarcely believing the order, the men obeyed with a reluctance that tested their sense of duty. Cooler heads prevailed and everyone fell back to the pits. A new order sent the men scrambling back through the torrent of fire to the jump-off point at the ridge’s base—this time with heavy loss.

“As he struggled up, up, up, shot and shell ripped into the ground and sprayed dirt into his eyes, temporarily blinding him. He felt hot puffs of sulfurous smoke against his face as he approached the cannons on the high ground.”

Now, the final quarter mile of the advance kicked off straight up the steep slope to the crest of the ridge. Confederate guns contested every inch of the way. “I have never seen anything so vicious as the artillery fire from the ridge,” recalled Maj. Leaming. “Grape, canister and shell flew through and over our ranks like a flock of birds.” As he struggled up, up, up, shot and shell ripped into the ground and sprayed dirt into his eyes, temporarily blinding him. He felt hot puffs of sulfurous smoke against his face as he approached the cannons on the high ground.

Lt. Col. Neff, out front, noticed how “man by man, as each would gather breath, firing as they went, the brave fellows rushed up, always onward, never backward for one moment.”

Gray gunners along the crest did their best to stop the blue juggernaut. Maj. Leaming recalled them depressing the guns so far that the blasts were tearing away chunks of earth from the edge of the ridge.

The national forces proved unstoppable. Lt. Col. Neff marveled as his regiment summitted Missionary Ridge and swept forward without stopping in pursuit of the broken rebel ranks. Neff paused and waited for the men behind him to catch up, and then continued the advance and captured prisoners, field cannon and abandoned supply wagons.

Success came at a heavy cost. About 20 Indianans died and 138 suffered injuries—roughly 45 percent of the regiment. Leaming joined the list after a gunshot left a nasty wound in his left ankle. He landed in a military hospital for treatment. Surgeons opted not to amputate, and medical personnel forwarded him to Nashville to complete his recovery.

A nurse follows a five-pointed star; a soldier meets his darlings

Sarah Elizabeth Dysart arrived at Hospital No. 1 in Nashville with the confidence of a veteran nurse that belied her 25 years. Born and raised on a sprawling estate west of the Pennsylvania capital of Harrisburg, Sallie attended Lewisburg Female Academy at Bucknell University as the war approached. On Feb. 22, 1861, she traveled from Lewisburg to nearby Harrisburg and listened to Abraham Lincoln speak from the portico of a local inn.

The President-elect, on the way to his inauguration in Washington, D.C., reassured the crowd that he would do all in his power to preserve peace and avoid bloodshed. Sallie came away inspired. “All that was good was with him—there was no bad,” she recalled.

On or about New Years Day 1862, as Leaming and his comrades prepared to leave Indiana for the South, Sallie started her service as a caregiver. Ordered to Harpers Ferry, Va., she joined the hospital staff of the hard-fighting 12th Corps and followed its five-star badge to Antietam, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. She proved a capable leader at Gettysburg, where she managed a ward at Camp Letterman.

Sallie formed a close bond with two fellow nurses: her cousin, Annie Bell, and Sarah Chamberlin. The trio accompanied the Corps into Tennessee and cared for patients at hospitals in Nashville and Chattanooga.

Exactly when Sallie met Leaming is currently lost in time. In a letter to his father dated June 12, 1864, she detailed her interactions with him as he approached death. She emphasized his failing health, noting that the attending doctor blamed Leaming’s condition on poor food in Chattanooga, as evidenced by the chronic bouts of diarrhea he had suffered since his arrival in Nashville. The doctor opined that Leaming’s foot should have been amputated immediately after he had been shot. Leaming kept it until just a week before Sallie wrote the letter. Ironically, the amputation had healed nicely, the healthy color of the fleshy stump a stark contrast to his deteriorating body weakened by disease and wracked by coughing fits.

Sallie had more to tell Leaming’s father about his son’s mental state and soul. Though not a Christian, (she was) he revealed to her in his lucid moments, he trusted God would spare him death. But if it came, he was ready.

“I asked him if I should tell his friends that he was resigned to die & go to Heaven where he should meet his two little darlings that had gone so lately before him,” Sallie stated. Leaming answered in the affirmative. Sallie then inquired if he had any final messages for his family. “He said not but give his love to all.”

Leaming lingered for a couple more days without any noticeable change. When occasionally regaining consciousness, he expressed his faith in a full recovery. On Tuesday evening, June 14, he revived and enjoyed a few spoonsful of chicken broth.

He breathed his last 15 minutes later.

Epilogue

Sallie was too worn out to finish the letter to Leaming’s father that fateful Tuesday night. She completed it the next day, offering her prayers and sympathies. That same day, brother Clay arrived at the hospital and received the news of Sylvester’s passing.

Sallie remained in Nashville and Chattanooga until the army discharged her in May 1865. A group of grateful patients gifted her a gold watch. Medical staff presented her with a star-shaped gold pendant set with a cross and pearls in appreciation for her service.

She returned to Pennsylvania and became involved in her church and charitable organizations, among them, temperance and missionary societies. Unmarried, Sallie succumbed to pneumonia in 1909 at age 71.

Melinda, widowed and without children, filed for and received a military pension from the government to compensate her for the loss of her husband. In October 1865, she married a local man, William Doty Yount, and started a new life. She and Yount settled in Champaign, Ill., and became parents to five children who lived to maturity. After Yount’s death in 1893, she remained single and died in 1928 at age 85.

The 40th Indiana Infantry soldiered on through the Atlanta Campaign before returning to Tennessee to fight in the battles of Franklin and Nashville. In the spring of 1865, the regiment received orders to New Orleans, and then on to Texas until the year’s end. A quarter century after the Leaming’s death, William F. Fox’s treatise, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War 1861-1865, listed the 40th as one of the “Three Hundred Fighting Regiments” in recognition of its high number of casualties.

Sylvester’s remains rest in grave 9,924 of the Nashville National Cemetery.

Special thanks to Ann Bays, who generously shared her family photographs and papers.

References: Sallie E. Dysart to George Leaming, June 12, 1864, Ann Bays Collection; 1850, 1860 U.S. Census; Family genealogy records, Ann Bays Collection; Sylvester Leaming military service records, National Archives; Melinda Dodson Leaming Yount widow’s pension file, National Archives; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; Index to the Executive Documents of the Senate of the United States, at the Special Session of March, 1863; The Soldier of Indiana in the War for the Union, Vol. 2.; Tyrone Daily Herald, Tyrone, Pa., Aug. 15, 1957; Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War 1861-1865; Busenbark, “40th Indiana Infantry: One of Fox’s 300 Fighting Regiments,” 40thindiana.wordpress.com

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Sylvester’s War: The journey of an Indiana volunteer from Tippecanoe County to Tennessee”

Comments are closed.