By Jeffrey I. Richman, with images courtesy of The Green-Wood Historic Fund Collections

During the first half of the 19th century, American cities rapidly expanded. As the living packed into urban areas, the numbers of dead increased. To meet the demand for burial plots, new cemeteries were established away from the hustle and bustle of city life and close enough to visit. These rural cemeteries, featuring landscaped grounds and an array of monuments and memorials, became popular destinations.

One of the first such spots in America, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y., was founded in 1838. By the time of the Civil War, it was the place for New Yorkers to be interred. And interred they are—575,000 and counting.

In 2002, Green-Wood rededicated New York City’s 1869 Civil War Monument at the cemetery. It occurred to me, as I thanked the re-enactors who had attended, that we should research our Civil War veterans. So, we started to identify them. I thought we might find 500 in total. We are now at 5,200!

The variety is extraordinary: 18 generals (16 Union and 2 Confederate), approximately 50 brevet Union generals, telegraphers, embalmers, the undertaker who designed President Abraham Lincoln’s catafalque that carried his remains up Broadway, leading war artist Edwin Forbes, Edward Anthony, who, with his brother Henry (in business as E. and H.T. Anthony) produced more images of the war than any other company, nurse Abigail Hopper Gibbons, and many more. We have found almost 100 Confederates, not one of whom had a gravestone contemporaneous with his burial that identified him as such. A disproportionate number of these Confederates were officers from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia who came North for business opportunities in the wake of the South’s economic collapse. Who knew that the provost marshal of the Army of Northern Virginia, David Bridgford, who signed many of the passes at Appomattox Court House that allowed Confederates to return home, is interred in Brooklyn?

For each veteran we have identified, volunteers have written a biography that appears on green-wood.com. Over the years, I have collected photographs and other items, on behalf of The Green-Wood Historic Fund, related to these veterans. In an unprecedented effort, we have applied for approximately 2,400 government gravestones for those who lie in unmarked graves; cemetery workers have installed them free of charge.

The high number of burials in Green-Wood Cemetery is perhaps no surprise. Brooklyn was an independent city at the time of the Civil War and ranked as the third largest city in the United States. Its vibrant economy attracted men and women from across the globe. In turn, many people with ties to the area chose to be interred in the majestically landscaped grounds of Green-Wood.

Here are representative veterans whose remains rest in Greenwood, illustrated with portraits from the collections of The Green-Wood Historic Fund.

Brooklyn and New York City natives

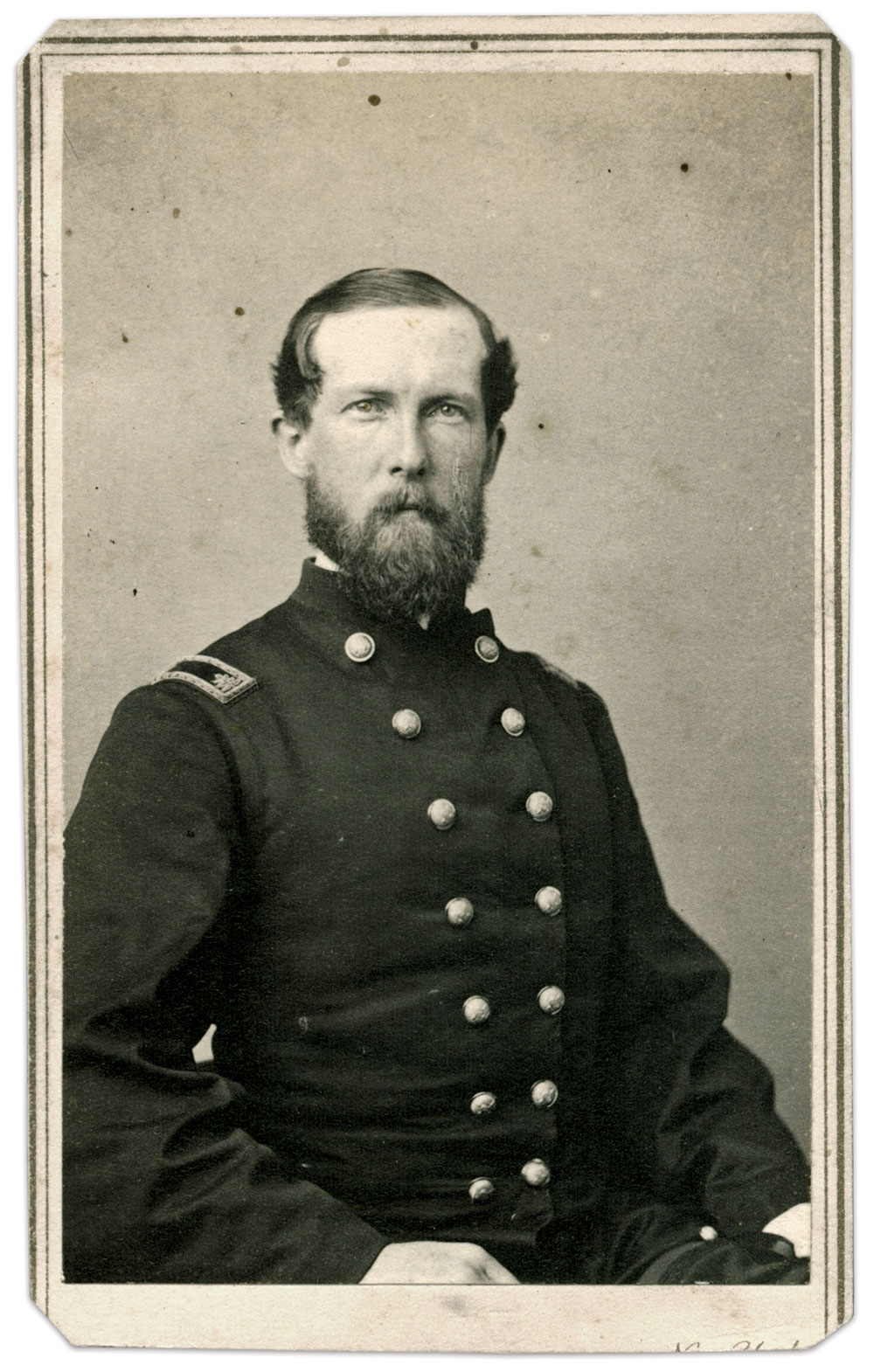

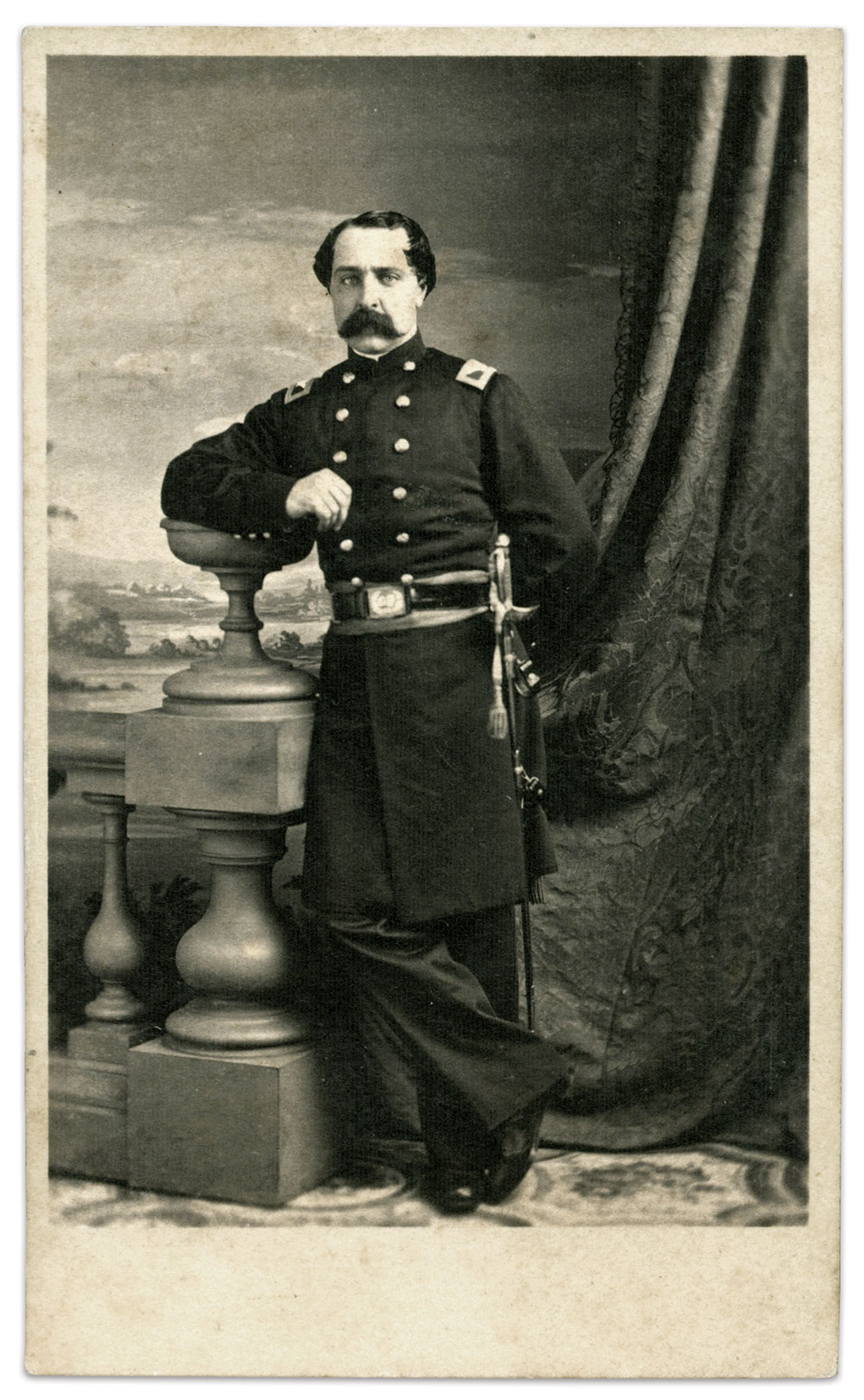

Lloyd Aspinwall (1834-1886) lived in New York City his entire life. He led a major trading company started by his father and served in militia and National Guard units before and after the war. As commander of the 22nd New York State National Guard and an aide to Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, Aspinwall delivered news of the Battle of Fredericksburg disaster to President Abraham Lincoln.

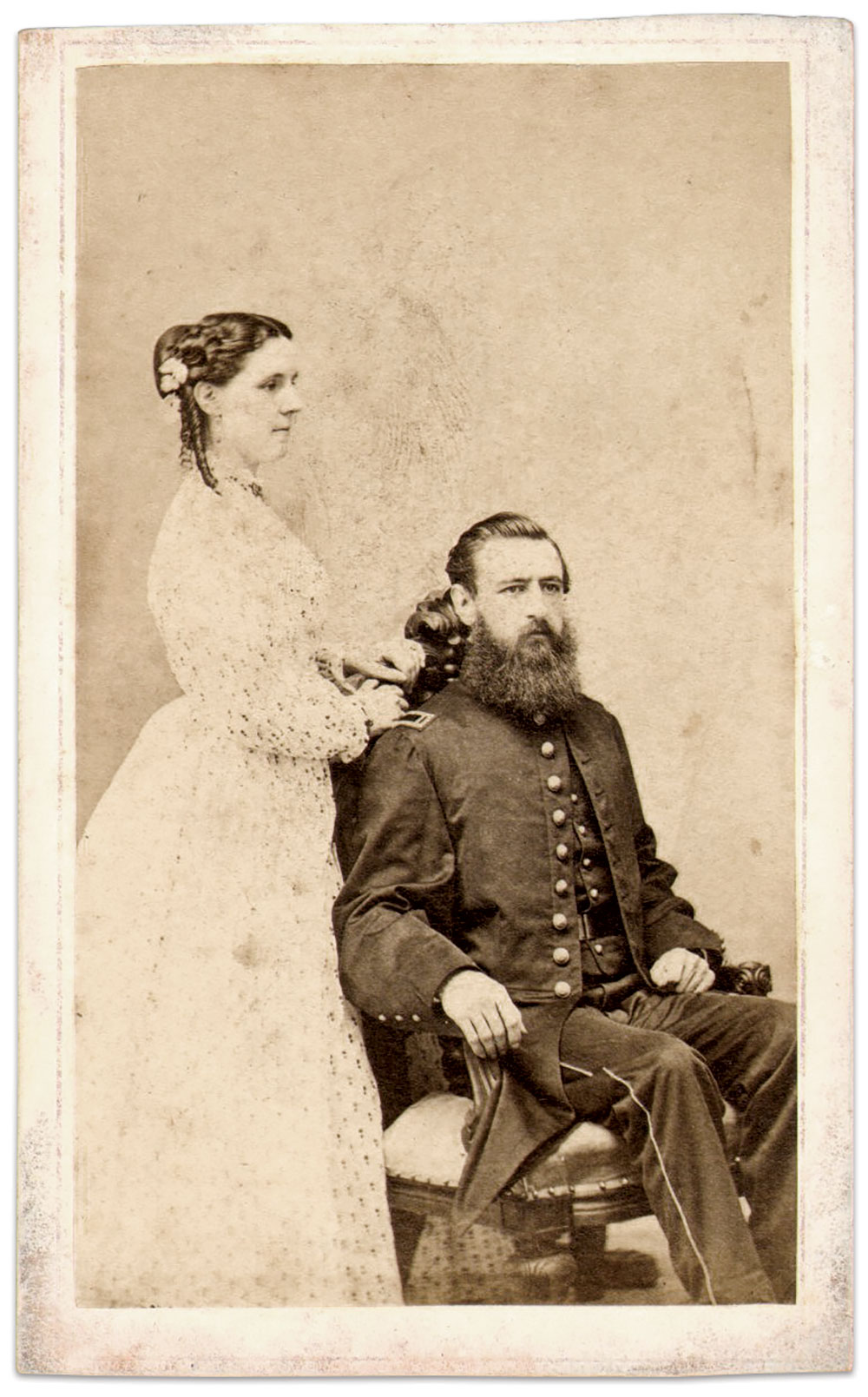

Dr. Jean Victor DeHanne (1834-1904) enlisted as a private in the 176th New York Infantry, and then served as an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army until his retirement in 1891. He is pictured here with his wife.

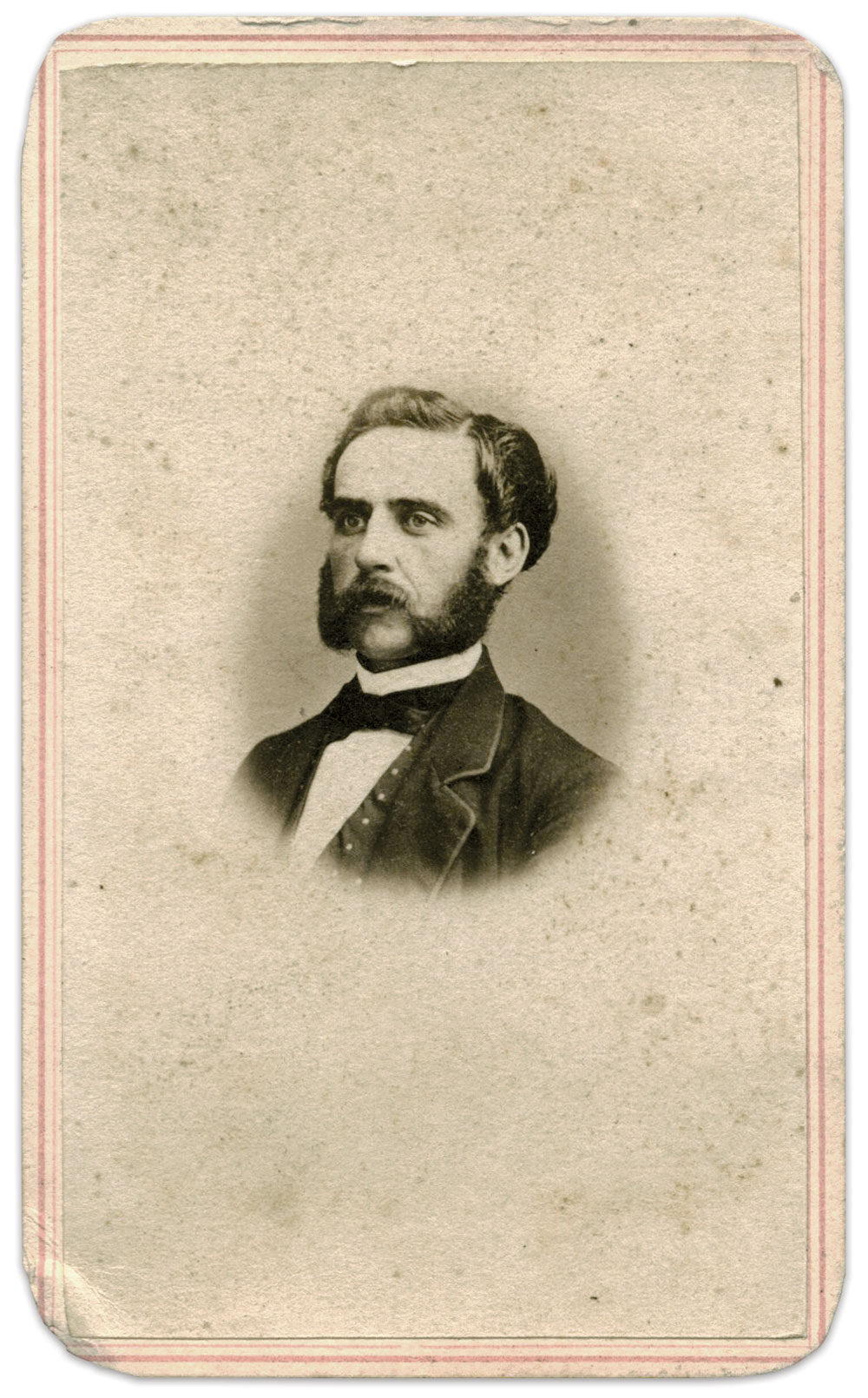

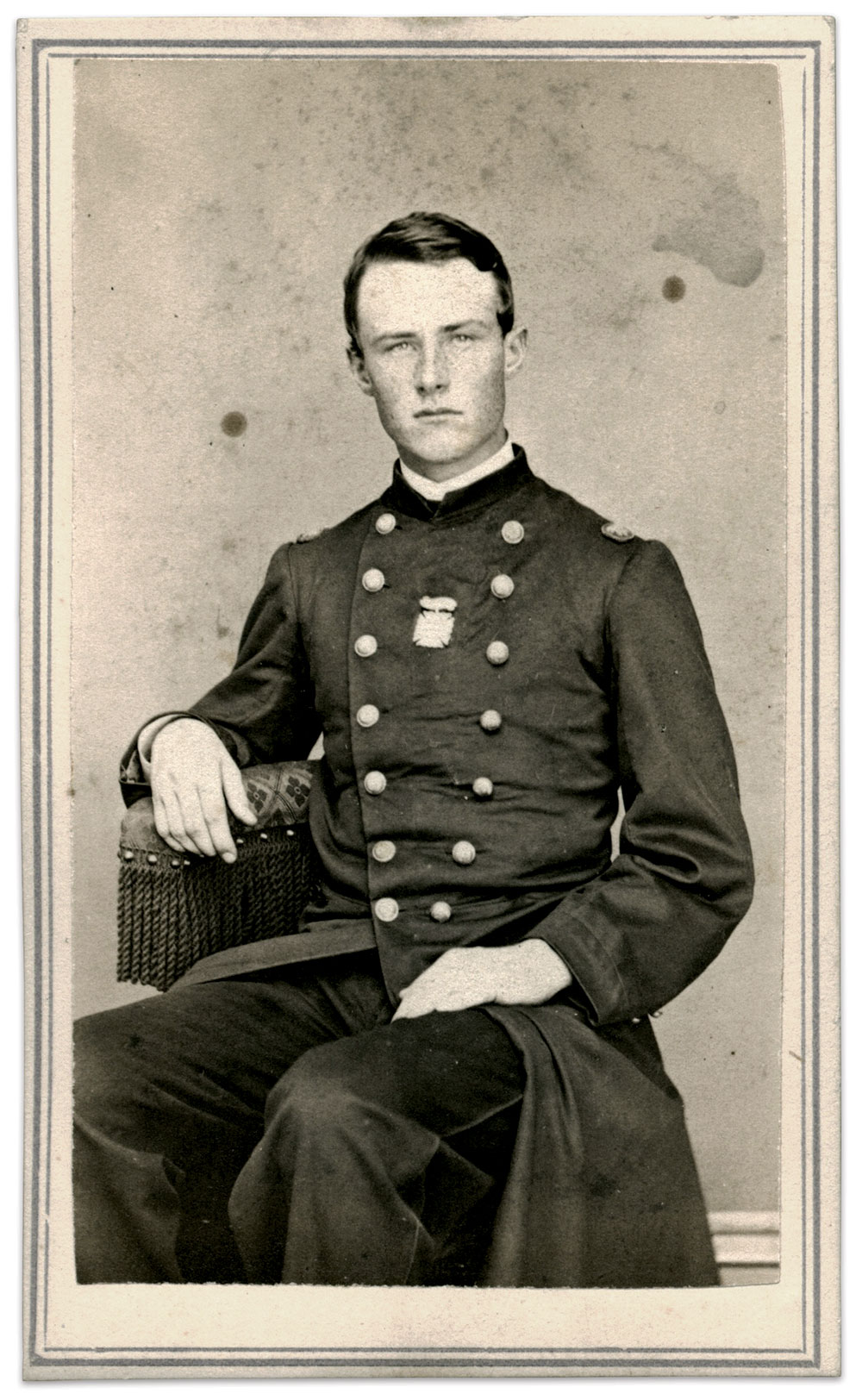

Brooklyn native George Alvan Burtis (1841-1898) served as sergeant major of the 165th New York Infantry. He worked as an accountant after the war and died in Manhattan.

John Howard Kitching (1838-1865) lived north of New York City in Dobbs Ferry before the war. As colonel of the 6th New York Heavy Artillery and commander of Kitching’s Provisional Division at Cedar Creek, he suffered a severe wound that proved mortal. He received a posthumous brevet as brigadier general.

Henry B. Hidden (1839-1862) served as a first lieutenant in the 1st New York Cavalry. During a mission near Sangster’s Station, Va., on March 9, 1862, Hidden commanded a small scouting party that encountered a much larger enemy force. Hidden ordered a charge that ended in his death. He was 23 years old. His audacious charge inspired poetry and artwork after the war.

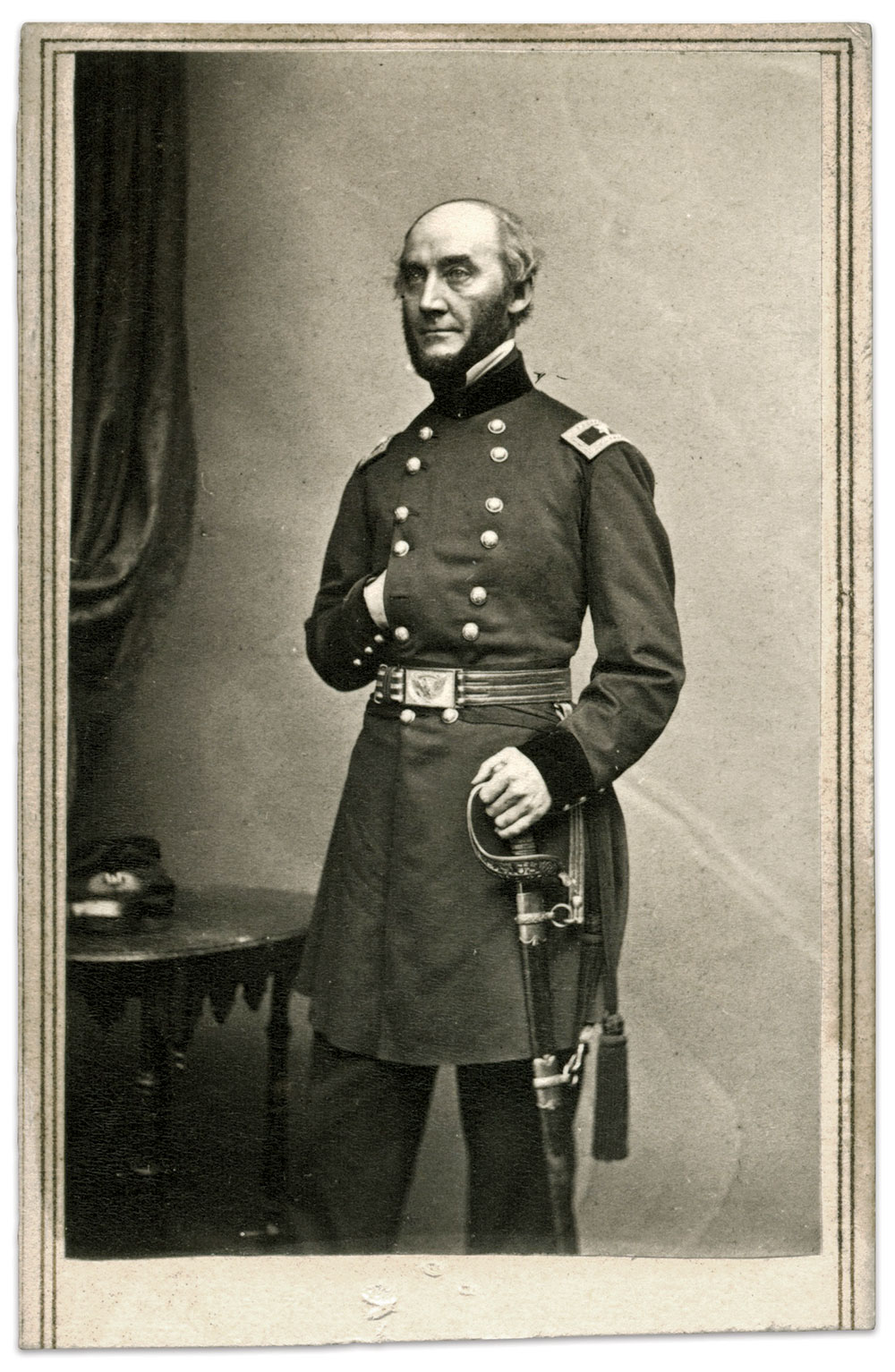

Though born in New York City, George Washington Cullum (1809-1892) grew up in Pennsylvania. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and career officer, he served as an aide to Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott and as Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck’s chief of staff during the Civil War. He went on to serve as superintendent of West Point and authored the classic resource Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy. He is interred in the same plot as Maj. Gen. Halleck. Cullum’s wife, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton Halleck Cullum, who was also Halleck’s widow and the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton, is interred between Cullum and his former boss.

of New York City.

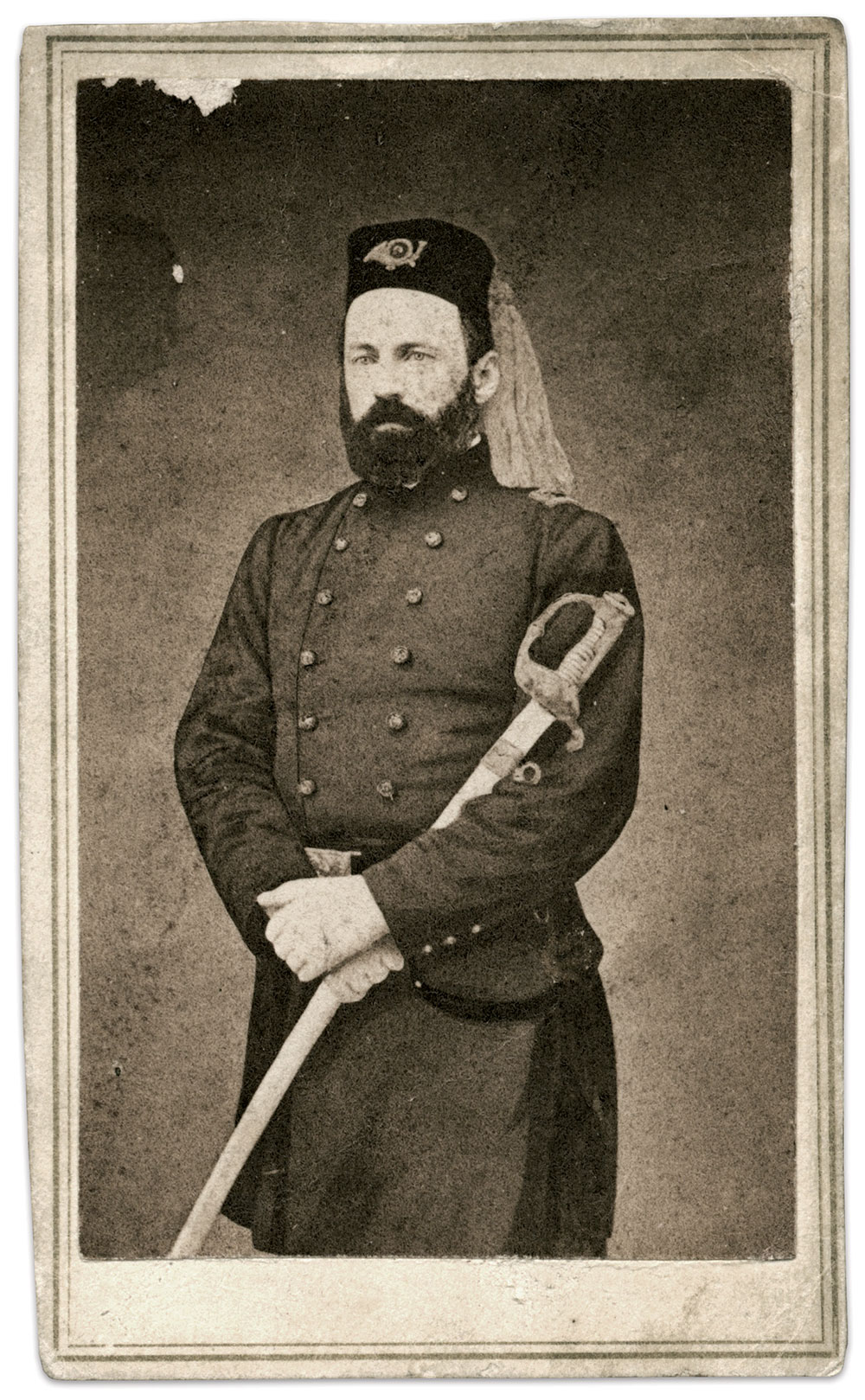

Abram Duryée (1815-1890), the organizer and namesake of Duryée’s Zouaves, the famed 5th New York Infantry, rose to the rank of major general during the war. He lived his entire life in Manhattan, serving after the war as New York City’s police commissioner.

Men from near and far connected to New York City before the war

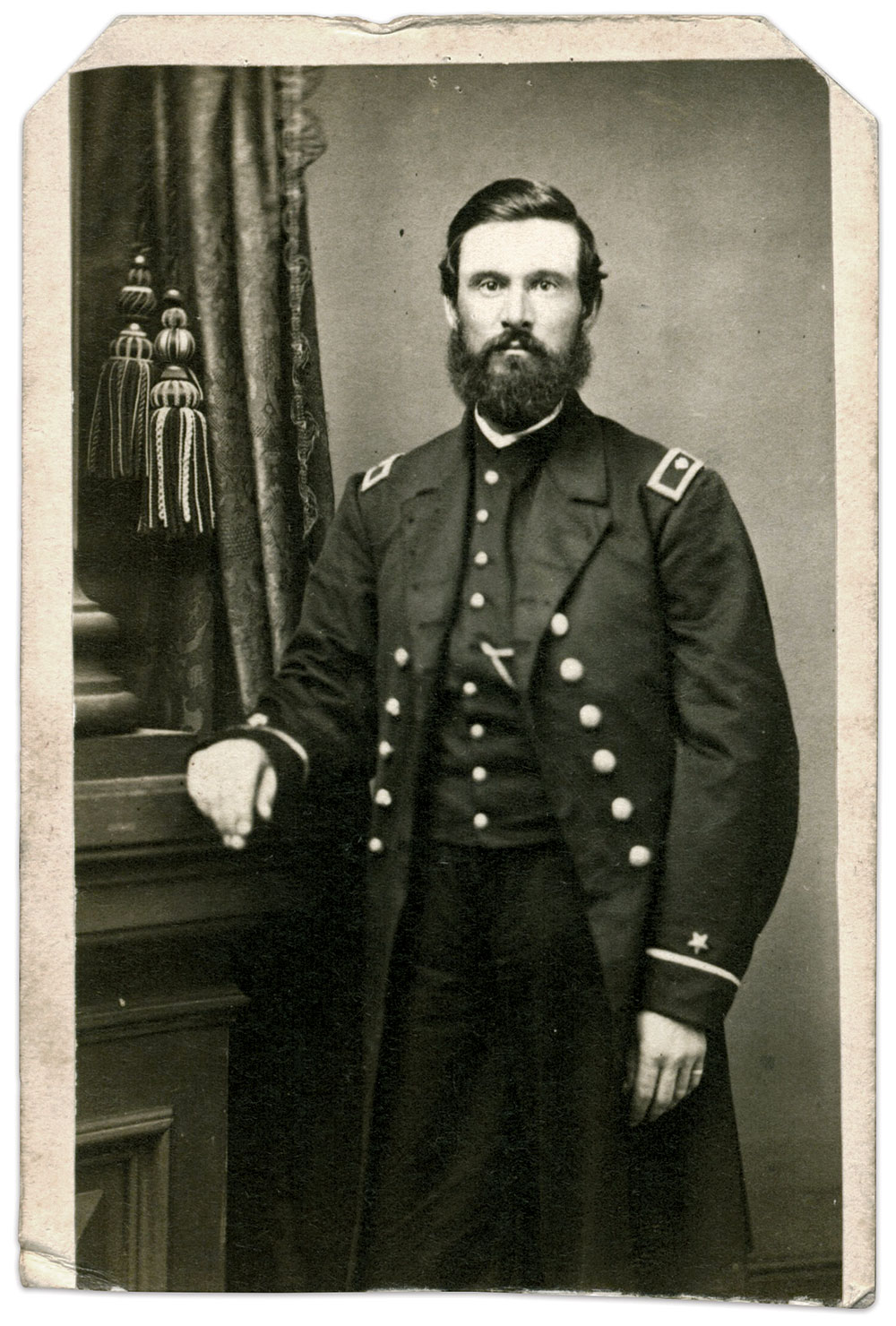

Edmund R. Greene (1830-1878) of Providence, R.I., served as a captain in the 83rd New York Infantry. After the end of his service, he returned to his native state, where he died of consumption.

Benjamin Nevers (1823-1877) of Boston, Mass., moved to Manhattan and served as major of the famed 7th New York State Militia. He survived the war and became a successful banker and a broker.

George Crockett Strong (1832-1863), a Vermont-born brigadier general, commanded his brigade, which included the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, in the 1863 attack on Fort Wagner, S.C. Wounded in the leg, he returned to his home in New York City to recuperate. But the wound became infected and, on the day his promotion to major general was approved, he died of tetanus.

New Hampshire’s Edgar Addison Kimball (1821-1863) published a newspaper in Vermont and served with distinction in the Mexican War. In the Civil War, he advanced from major to lieutenant colonel of the 9th New York Infantry, or Hawkins’ Zouaves, and led the regiment in the farthest advance by Union forces at Antietam, as well as at Fredericksburg. In early 1863, Brig. Gen, Michael Corcoran, the commander of the Irish Brigade, shot Kimball to death. Corcoran killed Kimball over an incident involving a password. Corcoran died before the end of the year after being thrown from a runaway horse.

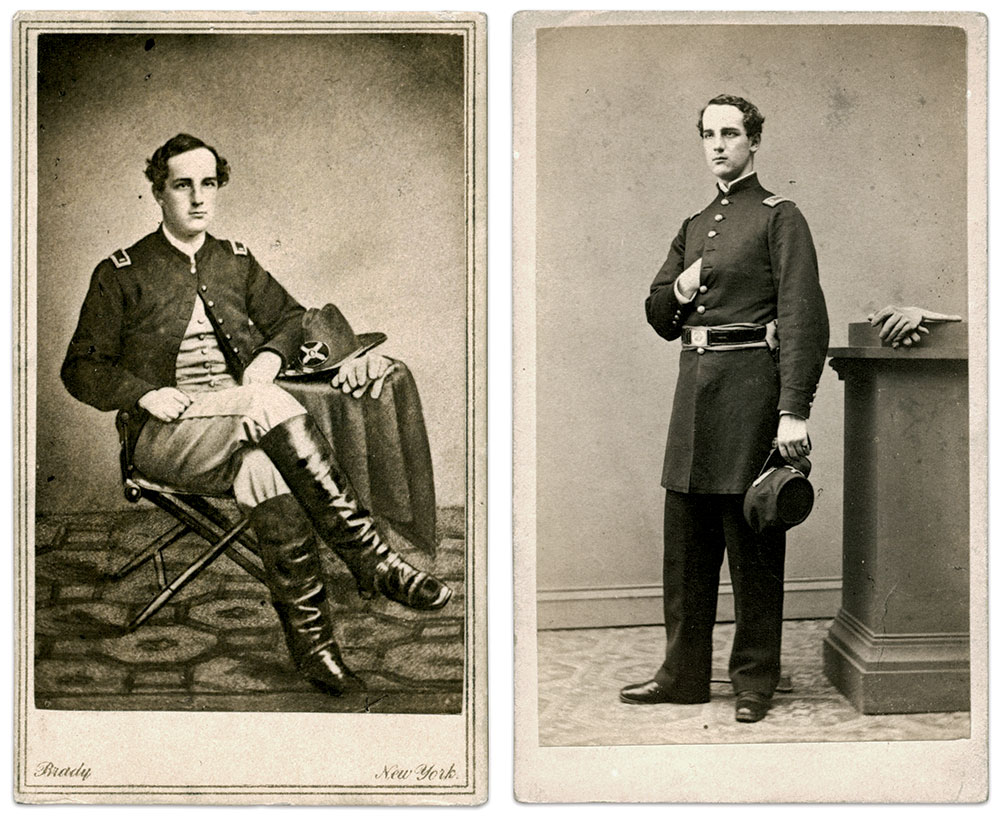

The Prentiss brothers, Clifton Kennedy (1835-1865) and William Scollay (1839-1865), are buried side by side in the cemetery. During the war, they stood on opposite sides of the conflict: Clifton, older by four years, served as major of the Union 6th Maryland Infantry. William served in the Confederate 2nd Maryland Infantry.

On April 2, 1865, the two Maryland regiments clashed with each other in the final frantic push to end the stalemate at Petersburg and Richmond. The brothers suffered mortal wounds within a short distance of each other. According to one account, William asked to see his big brother. Clifton refused: “I want to see no man who fired on my country’s flag.” Soon, stretcher-bearers carried William and lay him next to Clifton for a tearful reunion. Their Brooklyn connection happened to be an uncle. The marble stones marking their gravesites have deteriorated to the point that they are unreadable, and new stones have recently been installed in front of the originals.

On April 2, 1865, the two Maryland regiments clashed with each other in the final frantic push to end the stalemate at Petersburg and Richmond. The brothers suffered mortal wounds within a short distance of each other. According to one account, William asked to see his big brother. Clifton refused: “I want to see no man who fired on my country’s flag.” Soon, stretcher-bearers carried William and lay him next to Clifton for a tearful reunion. Their Brooklyn connection happened to be an uncle. The marble stones marking their gravesites have deteriorated to the point that they are unreadable, and new stones have recently been installed in front of the originals.

From upstate New York, 1st Lt. Franklin Butler Crosby (1840-1863) took command of the 4th U.S. Artillery on May 2, 1863, at the Battle of Chancellorsville. The next day, a sniper killed him. Among his personal effects included a copy of The Imitation of Christ with the following passage marked: “Fight like a good soldier; and if thou sometimes fall through frailty, take again greater strength than before, trusting in my more abundant grace.”

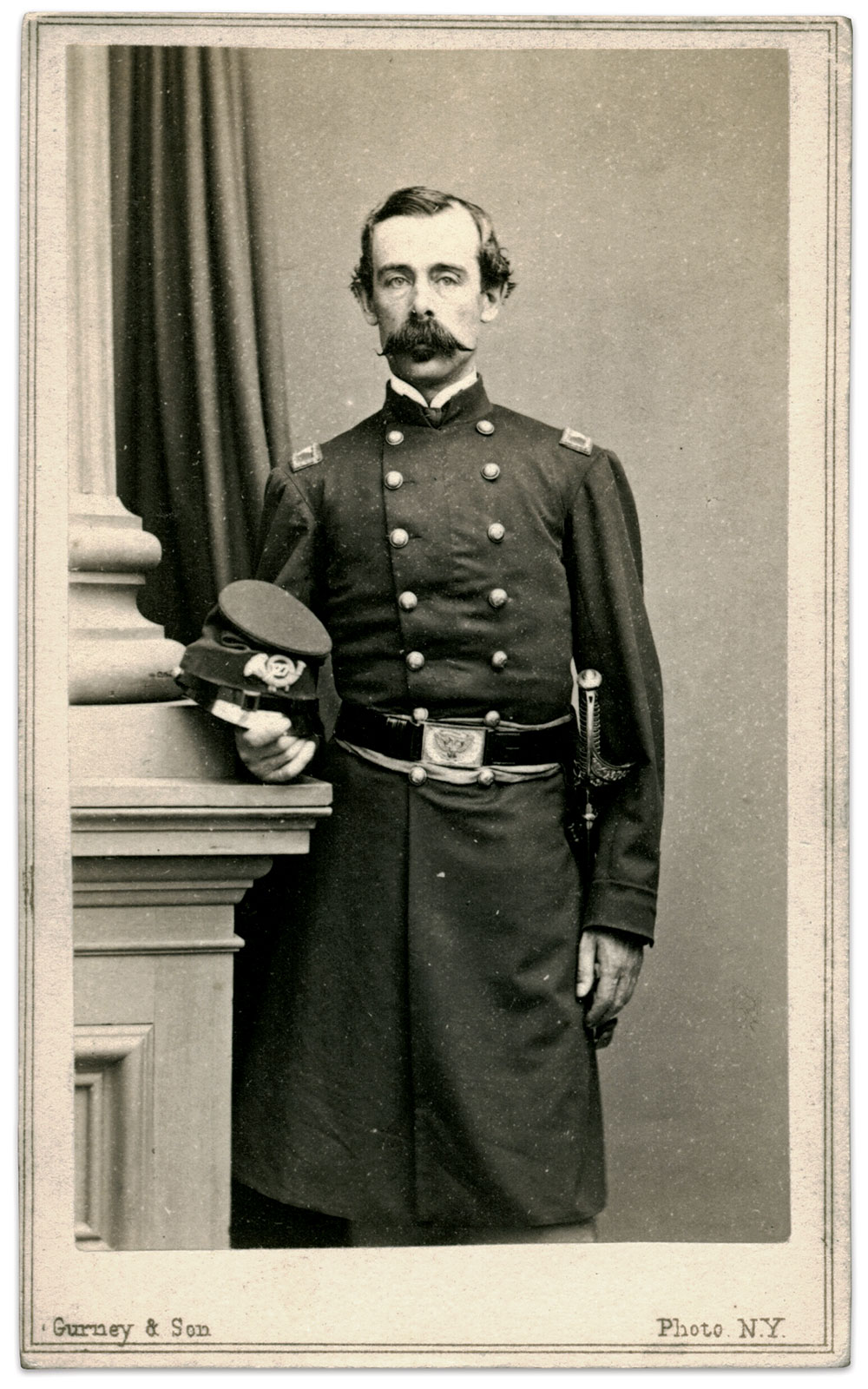

Born in Flushing, Queens, William Gurney (1821-1879) fought with the Army of the Potomac and rose to command the 127th New York Infantry. He led his regiment into South Carolina and received command of Charleston after the city fell to Union forces in early 1865. Brevetted a brigadier general, he remained in Charleston after the war and won election as county treasurer. His remains were sent North upon his death.

Marshall Lefferts (1821-1876) grew up on Long Island, moved to New York City, and joined the state militia as a young man. He led the 7th New York State Militia as it marched down Broadway just days after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. Lefferts died on July 4, 1876, on his way to festivities marking the centenial of the United States.

Born in Plymouth, Mass., John Faunce (1807-1891) rose to captain of the U.S. Revenue Marines. He commanded the cutter Harriet Lane on its mission to relieve the Fort Sumter garrison in April 1861, firing the first naval shot of the impending war.

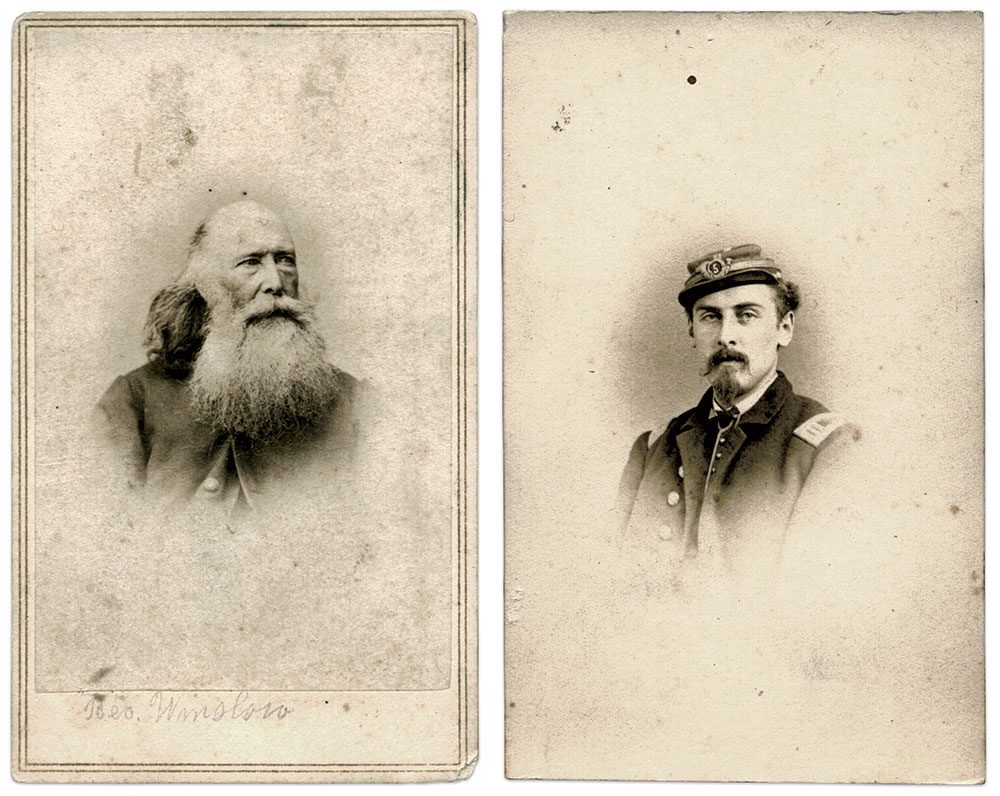

Massachusetts-born and New York City resident Gordon Winslow, a graduate of Andover and Yale and an Episcopal minister, enlisted as chaplain of the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry (Duryee’s Zouaves) in 1861 at age 58. He resigned two years later, and then assumed command of the U.S. Sanitary Commission’s field operations at Gettysburg. About a year later, his son, Cleveland, the colonel of the 5th New York Veterans, suffered a serious wound in the shoulder during the fighting at Bethesda Church, Va. Rev. Winslow came to the aid of his stricken son and accompanied him north for treatment. Along the way, on a transport vessel in the Potomac River, the elder Winslow drowned while attempting to fetch water. His body was never recovered. Cleveland’s wound proved mortal. His remains, along with another brother, Gordon, Jr., who also served the war, and their mother Katherine, are located in the cemetery. The elder Winslow is remembered on the grounds with a cenotaph.

Immigrants who settled in New York City before the war

Born on a steamer on the St. Lawrence River, John Bendix (1818-1877) grew up in Germany and immigrated to New York City. After the war started, he led the 7th New York Infantry at Big Bethel, Va., one of the earliest actions of the conflict. Bendix went on to command the 10th New York Infantry and receive a brigadier’s brevet.

Born in Grenada, Spain, to Italian parents, Edward Ferrero (1831-1899) and his family settled in New York City. He rose from West Point dance instructor to major general in the Union army’s 9th Corps. He is forever connected to his disastrous command of his division of U.S. Colored infantrymen at the Battle of the Crater along the front lines of Petersburg on July 30, 1864.

Thomas William Sweeny (1820-1902) of County Cork, Ireland, immigrated to New York City. He suffered the loss of an arm fighting in the Mexican War. During the Civil War he triumphed in Missouri and saved the day at Shiloh. After the war, he led the failed Fenian invasion of Canada.

They made New York City or Brooklyn home after the war ended

Medal of Honor recipient William Donaldson Dickey (1845-1924) of Newburgh, N.Y., began his military service as a first lieutenant in the 168th New York Infantry, and went on to become major of the 15th New York Heavy Artillery. In 1896, he received the nation’s highest military honor for his actions at the Second Battle of Petersburg. That same year, he moved to Brooklyn, where he lived until his death.

Granite State seaman John Y. Yeaton (1836-1903) served for six months in 1864 in the Union Navy as an acting ensign. He moved back to Portsmouth, N.H., following his enlistment, and then relocated to Brooklyn to work as a carpenter and builder. He died from injuries sustained after a train struck him.

Jeffrey I. Richman is Green-Wood Cemetery’s historian. He has been fascinated by the Civil War for decades. Jeff has authored three books, including Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, in Their Own Words(2007), and “The Gallant Sims”:A Civil War Hero Rediscovered (2016).

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.