By David B. Holcomb, with images from the author’s collection

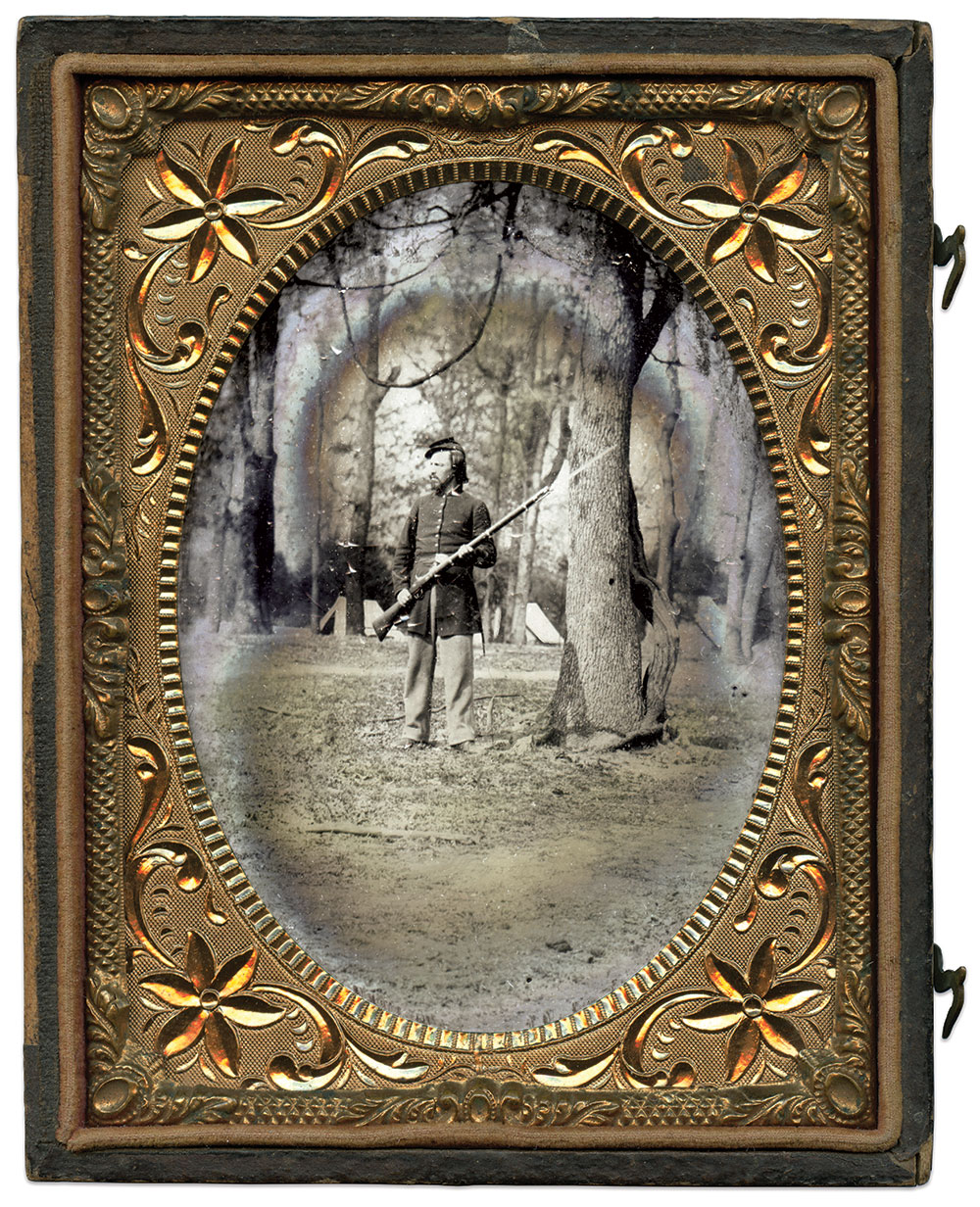

The Sentries

Around 8 a.m. following reveille, breakfast call, and sick call came the call for Guard Mounting. The first sergeant of each company turned out his detail for the next 24 hours’ duty, inspected them carefully, and marched them to the regimental parade ground. While the regimental band or the drum-and-fife corps provided appropriate music, the sergeant major formed the company details into line, after which the adjutant supervised their inspection and marched them to their respective posts. Details were so arranged that each member stood guard only two hours out of every six. The soldier pictured here appears facing outward away from the main camp, on the lookout for the enemy. But he also was tasked with keeping his comrades in camp to prevent foraging.

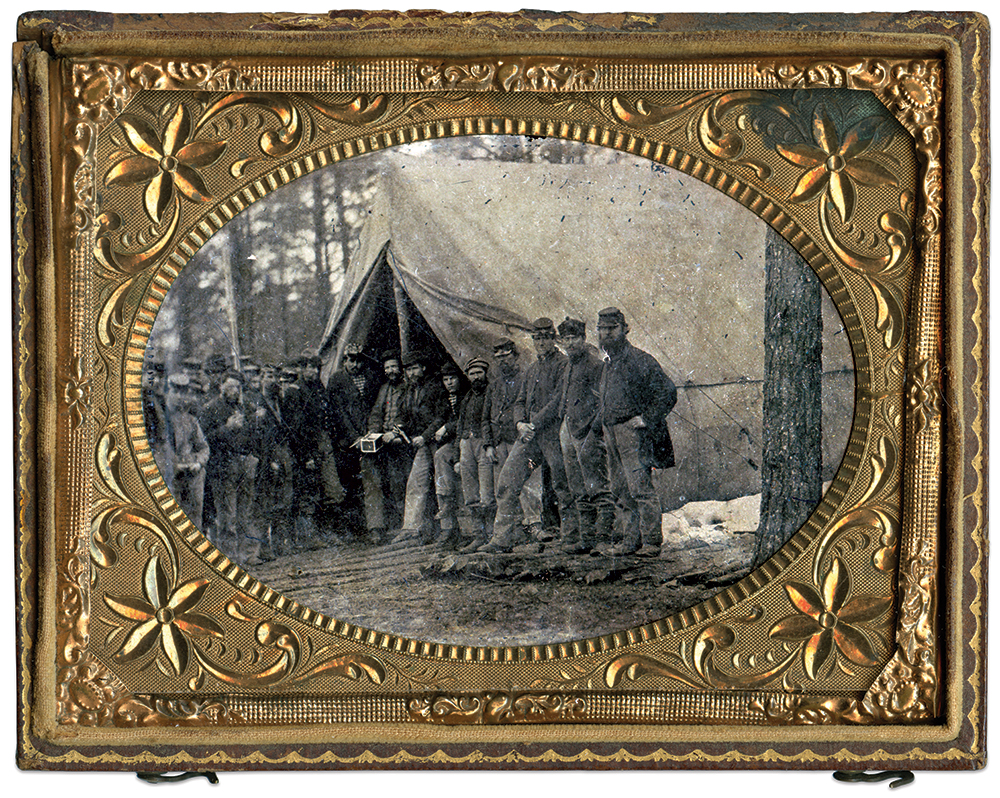

The Winter Quarters

Any visitor to an army in the field during the cooler months would likely happen upon clusters of tents and soldiers similar to this scene. A closer look reveals enlisted men, civilians and three officers. One officer straddles a fence rail, and another wears an Officer of the Day sash. This officer, usually a captain, had charge of the camp and received orders from the colonel or commanding officer. His tasks included maintaining good order, cleanliness, attention to the daily duties across camp and charge of the guards, who he inspected periodically throughout the day. One of his guards may be the armed soldier wearing a great coat and a Hardee hat.

The guard’s greatcoat suggests cooler weather. The stockade tents with barrel chimneys reinforce this—a sign that these quarters were built for warmth and an extended stay. The leaf-bearing trees suggest early autumn or late spring.

The log tent walls were built “cob-fashion” by notching them together at the corners. The “A” or wedge tent raised over this stockade resulted in a structure roughly 7-feet square, providing shelter for four soldiers. Such tents were considered spacious and comfortable considering the alternatives.

Barrels and at least one storage box suggest the presence of a company cook.

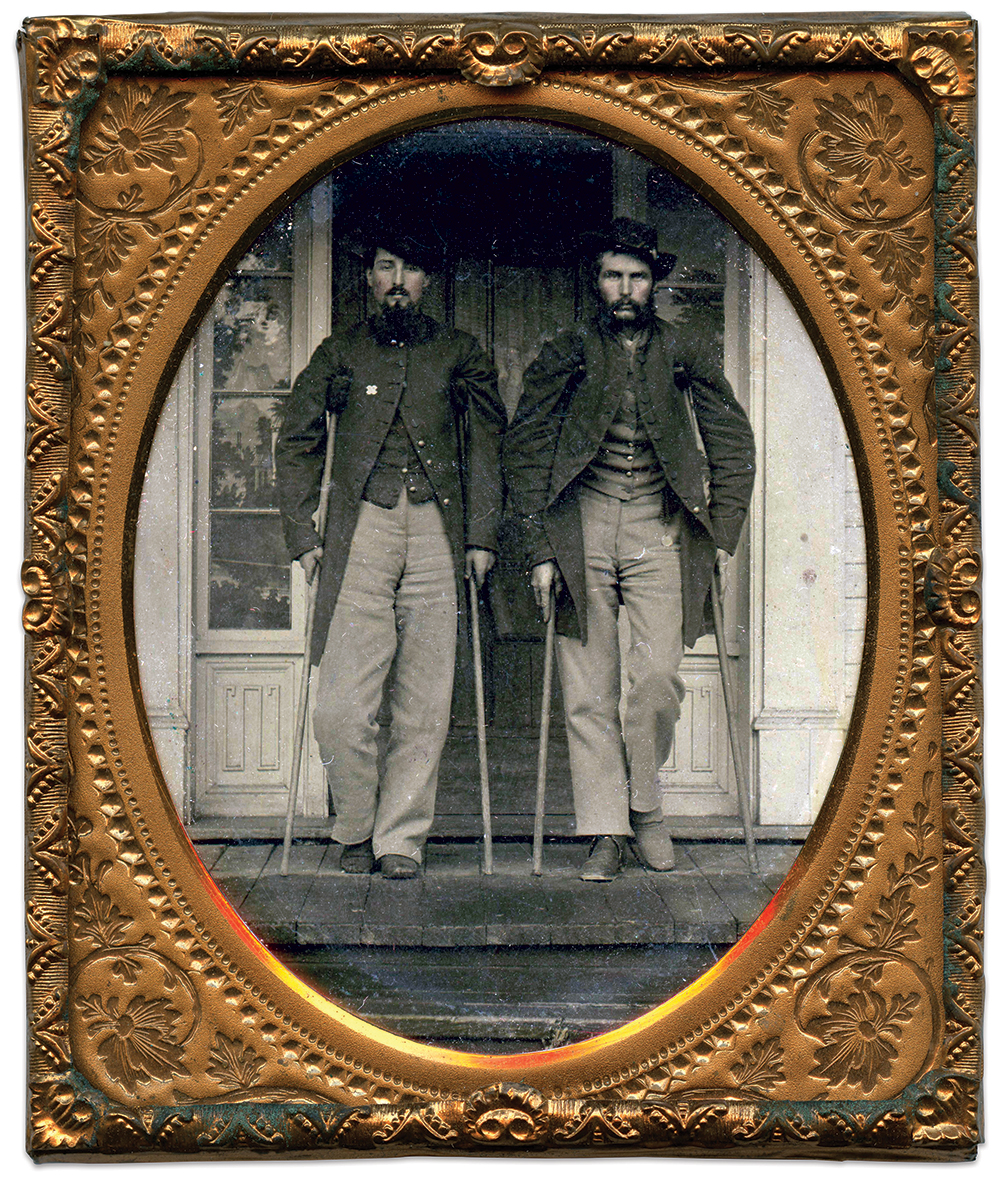

The Wounded

During the Civil War, knowledge of germ theory lay decades in the future. Most operating tables were located in the open air to take advantage of good light, though some were located under cover for protection against the elements. Surgeons stood with their arms covered in blood to the elbows, with surgical knives held in their teeth when moving a wounded soldier, and aprons smeared with blood and gore near piles of amputated limbs. The scene of a Civil War operating team in action from the 1990 movie Dances With Wolves was quite accurate.

It has been suggested that it would have been safer for a soldier to fight through all three days at Gettysburg than it would have been to subject himself to amputation or the setting of a compound fracture. These soldiers with crutches standing on a porch were fortunate indeed.

The Recruits

Gatherings like this one took place in boroughs, villages and towns across the North during the war. The soldiers and musicians who lined up behind the Stars and Stripes, along with the Honest Abe lookalike beating the drum, may have just enlisted or reenlisted.

The Mules

It has often been said that the South would not have been bested had it not been for Northern mules. When the war broke out, soldiers by the thousands descended on Washington, D.C., and assembled across the North. To supply them with rations, forage and equipment, large numbers of wagons were employed.

Horses and mules pulled them at first. As the army grew, so did the need for horses in cavalry regiments, each requiring 1,200 mounts, and light batteries, 110 each. Add to this replacements for those lost to disease, exposure, and killed in action. As a result, horses were diverted from supply trains—leaving sturdy mules behind.

Nervous by nature and unsuited to combat, mules became the mainstay of ammunition, forage, supply and bridge trains.

Here, a quartermaster sergeant stands beside a Third Corps wagon pulled by a six-mule team. The driver, riding the near pole mule, holds a single reign in one hand and a “black snake,” or black leather whip, in the other.

The Sutler’s Tent

The most popular man in camp was undoubtably the sutler. Dry goods merchant and local grocer, he made available a unique inventory that no regimental quartermaster could match: butter, flour, tobacco, canned goods, sweets, and more. In effect, the sutler acted as an early Post Exchange or PX.

The sutler could also be the most reviled. Price gouging irked more than one soldier who believed the sutler charged too dear a price for his wares. Another complaint: Issuing metal or cardboard tokens in various denominations to make change for greenbacks. Of course, the tokens could only be used at the sutler’s tent—the company store trap.

In defense of sutlers, it is fair to state they operated a high-risk undertaking filled with wartime uncertainties and logistical challenges.

This scene might be a group of customers in front of the sutler’s tent. The civilians in the center showing off a box of cigars and a bottle may be the sutler and his assistants. The soldiers surrounding them appear satisfied for the moment. One can imagine the expressions of these troops might be different when the sutler’s bill comes due. One trooper holds a bottle. It might be assumed that it held alcohol but that would be unlikely given that army regulations governing sutlers forbade the sale of spirits.

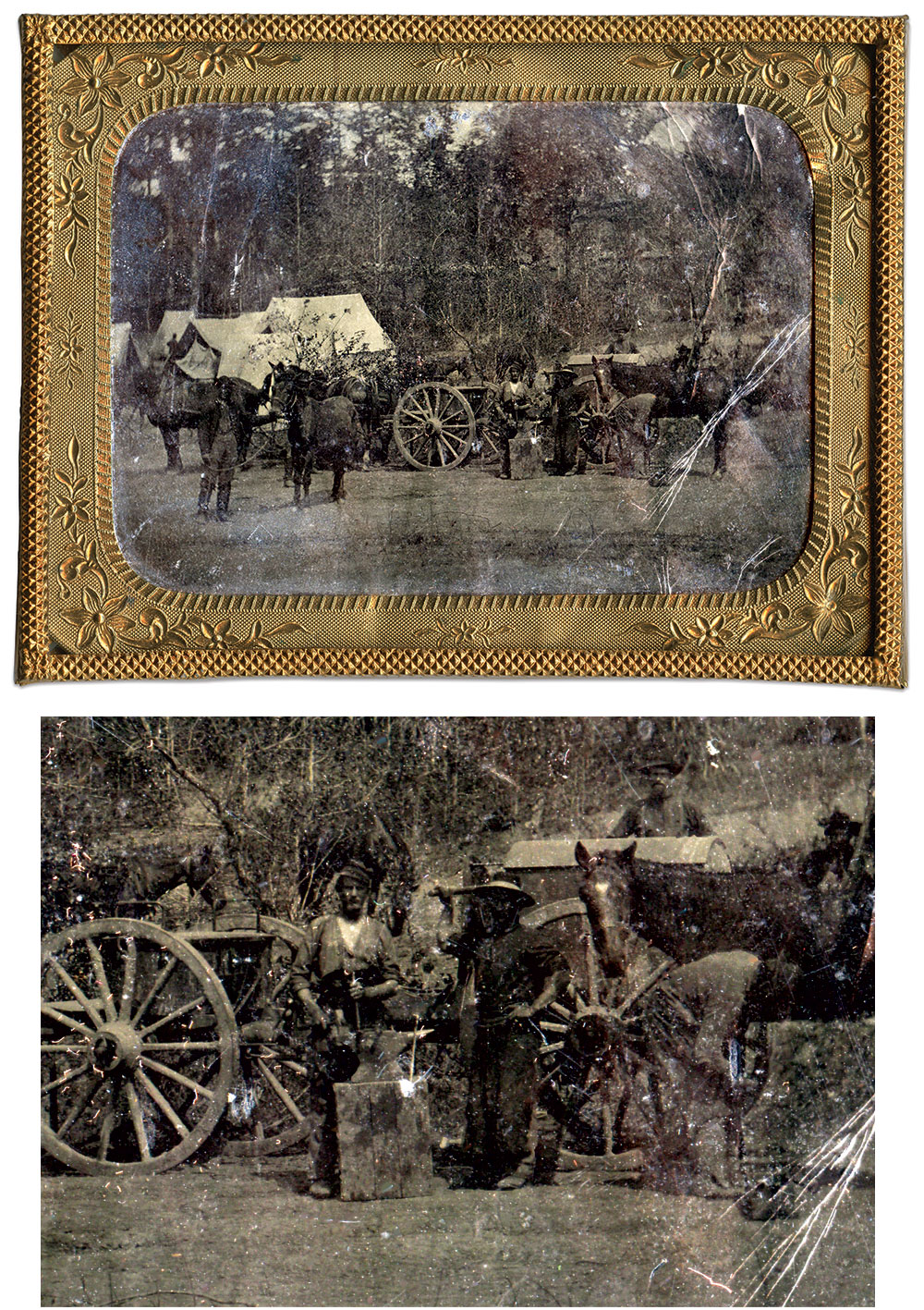

The Blacksmiths

“Wagon busted, axle broken, and wheel gone to smash” was a common refrain heard up and down supply trains line during a hard campaign. Poor, miry and rock-strewn roads destroyed the best-made wagons—and took a toll on mules and horses. Loose, damaged or lost shoes added to the ongoing challenge to keep the trains moving and the cavalry and artillery in motion.

Skilled workers of many trades, known as artificers, labored from dawn to dusk to keep the armies advancing. Military regulations specified the required skills: “No man, unless he be a carpenter, joiner, carriage-maker, blacksmith, saddler, or harness maker, will be mustered as an artificer.” Another key position, farrier, shoed horses and mules.

According to the Quartermaster Department, “horses of a field battery will be shod by the artificers of the company, one of whom shall be a farrier. No other compensation than the pay and allowances of that grade will be made for these services.” Also, that “horses of the mounted officers shall be shod by the public farrier or blacksmith.” It assumed the officers paid for work with their own funds. (The same order applied to Gen. George Washington in the Revolution nearly a century earlier.)

The men here were connected to a field blacksmith operation. Note the traveling forge (the domed roof behind the caisson), anvil, artificer-blacksmiths and at least one farrier. The anvil in the center of the image is flanked by an artificer-blacksmith and a farrier dressed in leather smocks and armed with get- and sledgehammers. The horse being shoed stares towards the camera as the farrier works.

The Contrabands

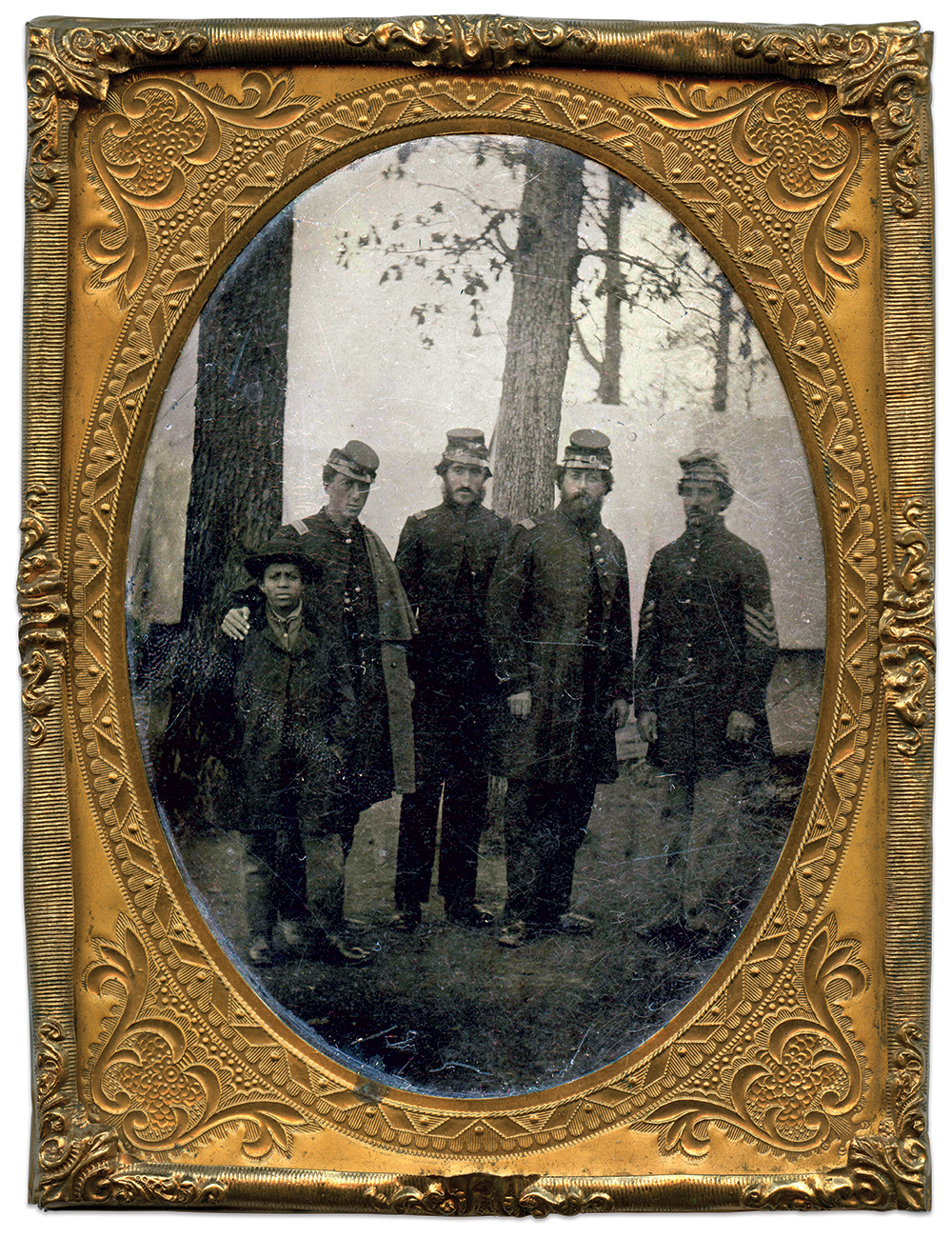

A trio of Union officers and a sergeant stand in front of a tent with a boy. The events that brought them together for this tintype are currently lost in time. Also unknown are their fates—especially the boy, who had likely been enslaved prior to joining these soldiers.

The expression on the boy’s face resembles a thousand-yard stare, the unfocused look of soldiers who have seen the horrors of war. In his case, he has no doubt witnessed his own horrors as a slave, and experienced loss and trauma as a result.

The officer standing behind him, with his hand resting gently on the boy’s shoulder, offers comfort and support. It is evident he cares about the well being of this boy. The other three men stand with them in solidarity of purpose.

The boy would have been known as “contraband” throughout the army. How this name came into existence is almost as old as the Civil War itself. Early in the conflict, Union commanders were expected to return slaves who crossed into their lines. This policy did not sit well with them. In May 1861, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler decreed that he would not return slaves who might be forced to support the Southern war effort. Instead, he declared these slaves to be “contraband of war” and not be returned to enslavement.

President Abraham Lincoln worried that border states might renounce their support of the Union and align with the seceded states should Butler’s declaration be implemented. Congress ignored his concerns and passed the Confiscation Act in support of Butler’s actions. A year later, Congress expanded the law with the passage of the Second Confiscation Act. These Congressional actions amounted to a de facto Emancipation Proclamation, but one only realized in Southern areas under Union control.

References: Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union; Billings, Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life; Miller, ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes, Vol. VIII; Orndorff, Blacksmith’s Traveling Forge History and Specifications; U.S. War Department Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861; Book of Old Time Trades and Tools; Encyclopædia Britannica, “Confiscation Acts;” Wilbur, Civil War Medicine 1861-1865.

David Holcomb of Worthington, Ohio, has collected historic photography since the late 1970’s. He sold the bulk of his collection through Cowan’s Auctions in 1999 to raise funds for a commercial building and did not acquire a single image for 12 years as he raised his kids and built his business. In 2012, he returned to collecting with a focus on the Civil War, the Old West and fine daguerreotypes.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.