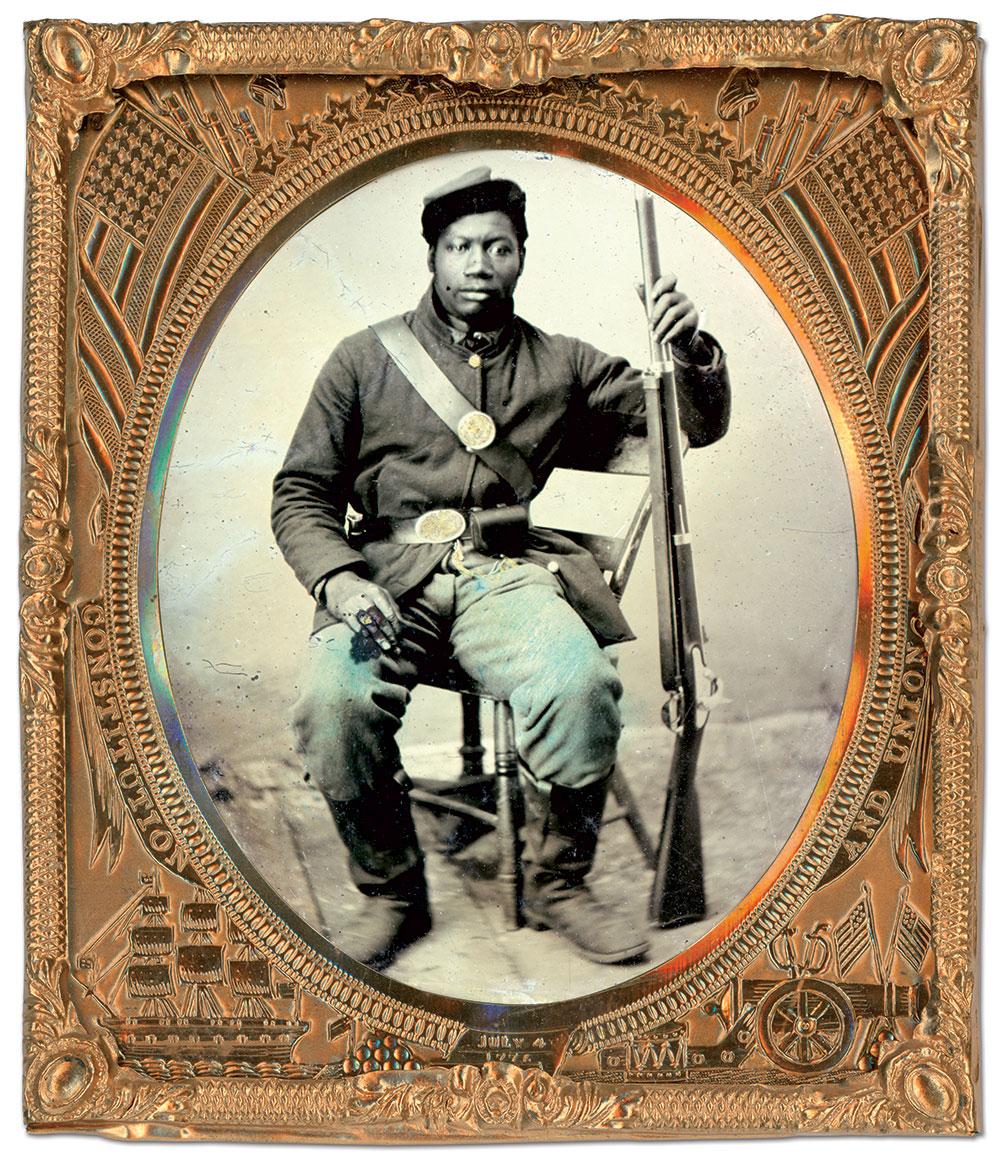

These portraits of infantrymen posed with Model 1861 Springfield rifled muskets evoke the celebrated Conkling Letter penned by Abraham Lincoln on Aug. 26, 1863. Written for a mass meeting of Union men in his hometown of Springfield, Ill., Lincoln, unable to attend, sent New York politician James C. Conkling to read it aloud to the audience.

In this passage, Lincoln addresses those who objected to the implications of the Emancipation Proclamation:

“You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.”

“I thought that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the enemy in his resistance to you. Do you think differently? I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union. Does it appear otherwise to you? But negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept.”

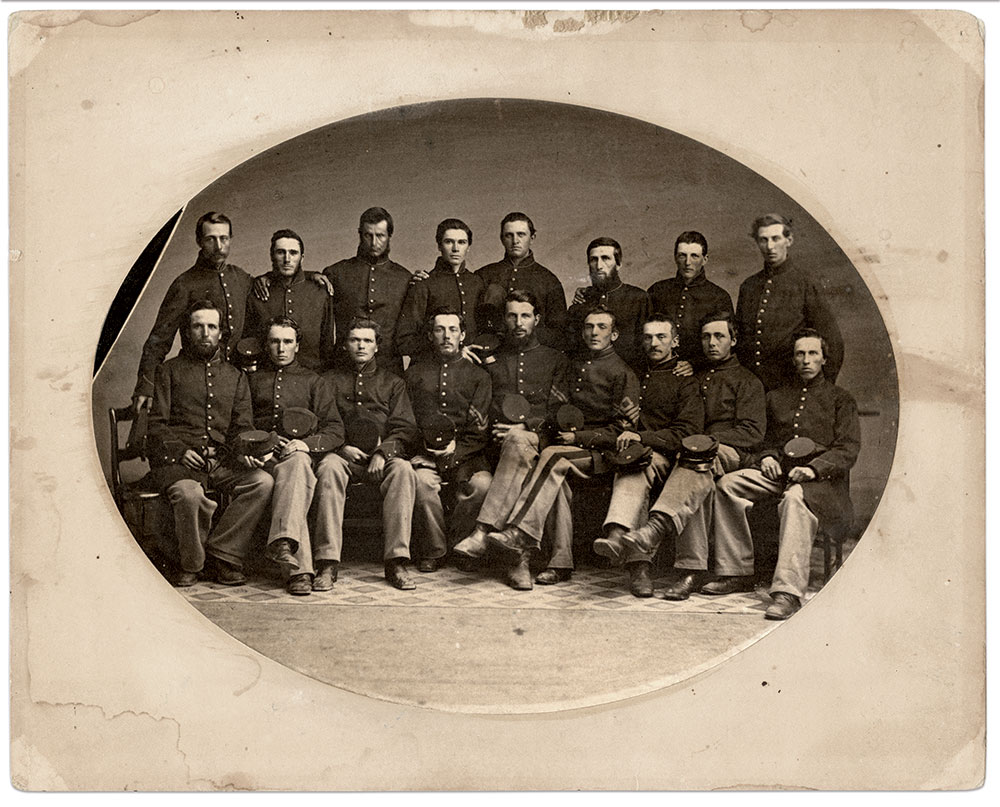

Members of Company E, 44th New York Infantry, posed for this early war portrait after they enlisted in the summer of 1861. In the center sits Helim Thompson (1839-1907), a mountain of a man at 6-foot-4-inches and 200 pounds. He suffered multiple wounds on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. (For more information and a carte de visite of Thompson, see the Summer 2021 issue.)

To date, five other men have been identified:

To Thompson’s left sits Cpl. Oliver W. Sturdevant (1835-1912), who received his sergeant’s stripes before leaving the regiment to accept a captain’s commission in the 10th U.S. Colored Infantry. Next to Sturdevant sits Pvt. William Royal (1841-1920), who went on to become a captain in the 9th U.S. Colored Infantry and a postwar agent for the Freedman’s Bureau in Georgia. To Thompson’s right, 1st Sgt. Consider Heath Willett (1840-1912), who left the regiment to join the 2nd U.S. Colored Infantry as a captain.

Standing immediately behind Thompson is Pvt. Charles F. Dorrance (about 1840-1864), who received a disability discharge in July 1864 and died the following month. Standing on the far right is Pvt. Thompson Barrick (1838-1892), who suffered a gunshot wound in the neck on Little Round Top. He recovered and joined the 39th U.S. Colored Infantry as a first lieutenant and ended his service as a captain.

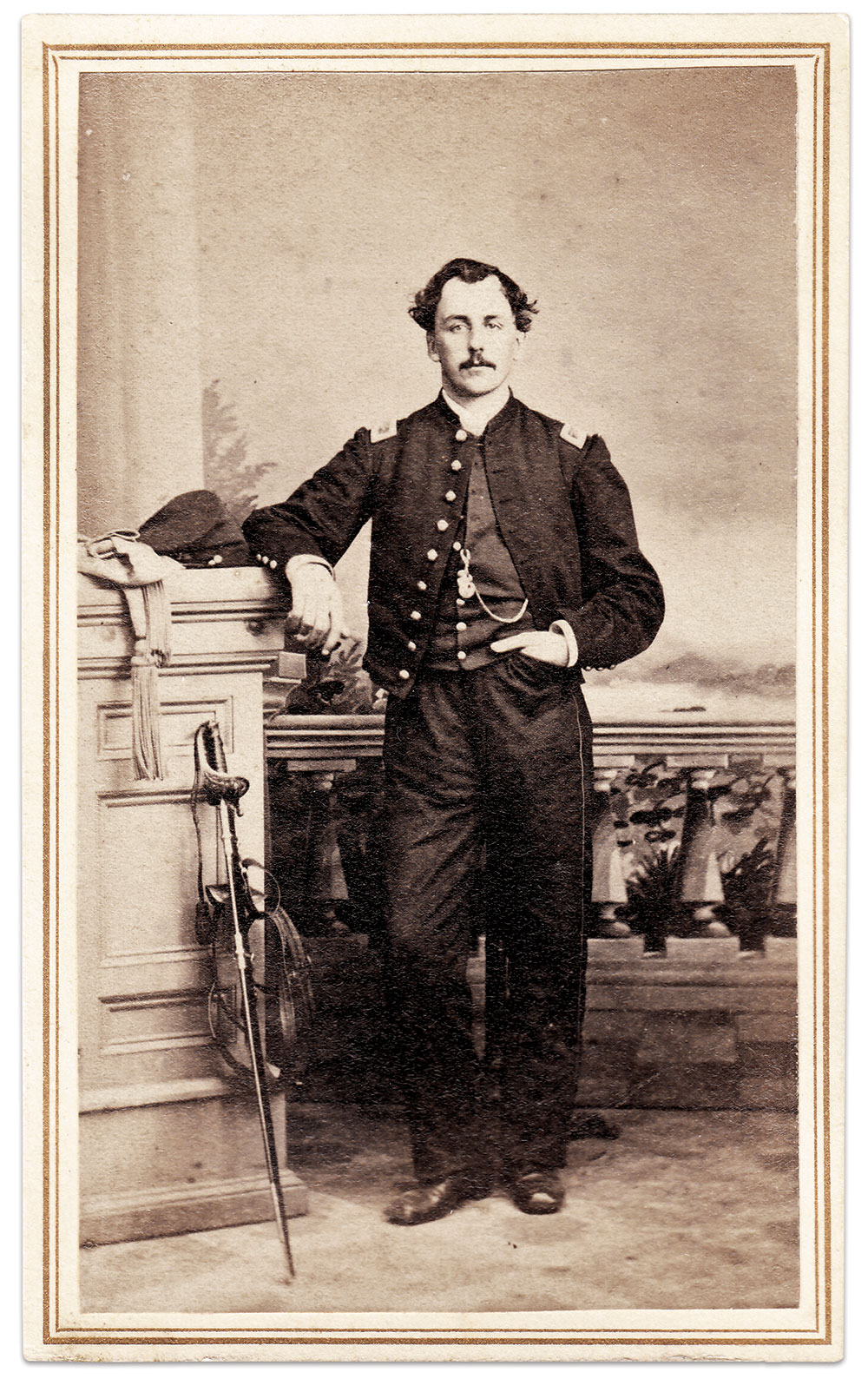

Henri B. Loomis poses with a sword and belt presented to him by the members of Company F of the 56th New York Infantry on Dec. 30, 1862. On that day, his promotion from sergeant to second lieutenant became official, and his comrades marked the occasion with this Model 1850 sword. The basket hilt and fancy quillon suggests it may be a Clauberg/Horstmann variation.

The 56th started its service with the Army of the Potomac. After the Peninsula Campaign, it relocated to South Carolina for the remainder of its enlistment. Loomis advanced to first lieutenant and regimental adjutant in late 1863, and served in this capacity through the end of war. From July to October 1865, the 56th policed the western district of South Carolina with headquarters in Newberry. Loomis, as adjutant, authorized the issue of various orders to the civilian population.

After the 56th mustered out, Loomis made his way west to Richmond, Ind., where he worked as a salesman. In 1888, he entered the Soldiers’ Home in Dayton, Ohio, and died seven years later of influenza at about age 53. He never married.

In one of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s acts to protect his retreat routes on July 3, he ordered his cavalry chief to guard wagon trains parked at Fairfield. Lt. Gen. JEB Stuart dispatched a brigade of Virginia troopers to the village, located about eight miles west of Gettysburg.

The brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones, saddled up and rode off to execute orders. The Virginians made it to within two miles when they encountered the 6th U.S. Cavalry. Jones deployed two of his regiments, the 6th and 7th, and held his third regiment, the 11th, in reserve.

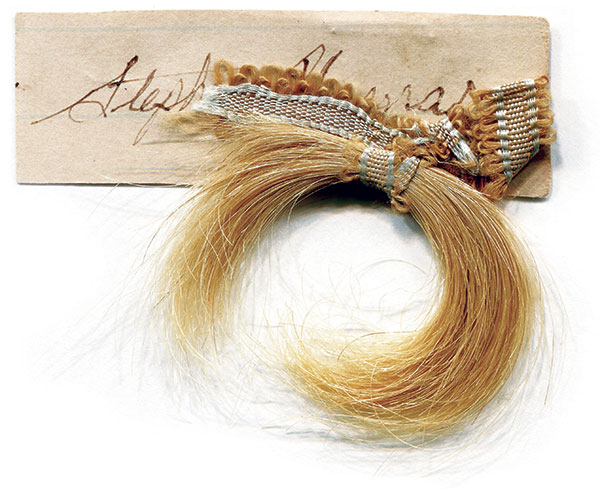

In the ranks of the 11th rode Stephen Hannas, a Virginia native from the Hampshire County town of Romney on the western edge of the Shenandoah Valley. Back in October 1861, just a week after he celebrated his eighteenth birthday, Hannas enlisted in the 77th Virginia Militia. In March 1862, the 77th reorganized in Winchester, Va., and became part of Col. Turner Ashby’s 7th Virginia Cavalry. Three months later, Ashby lost his life during Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign. Hannas and Ashby’s other men became the 17th Battalion Virginia Cavalry. In early 1863, the 17th joined with two other units to form the 11th.

At Fairfield on July 3, Hannas and his comrades remained in reserve as their brother regiments soundly defeated the federal cavalry. Jones sent in the 11th for cleanup operations. The regiment spent the rest of the day on picket, rounding up prisoners from the recent fight. At some point, Hannas suffered a shoulder wound. He returned to his command at the end of August.

In January 1864, he slipped out of camp, with his saber, a pistol and a Burnside carbine, and never returned to the regiment. A year later in Romney, he married and started a family that grew to include 11 children. A farmer during his working life, Hannas joined his local United Confederate Veterans’ camp and remained active until his death at age 70 in 1912. His wife, Sarah, and many children survived him.

It is believed Hannas posed for this portrait in Winchester. The image has appeared in two books: William A. Turner’s Even More Confederate Faces (1983) and 11th Virginia Cavalry, part of the Virginia Regimental Histories series, by Richard L. Armstrong (1989).

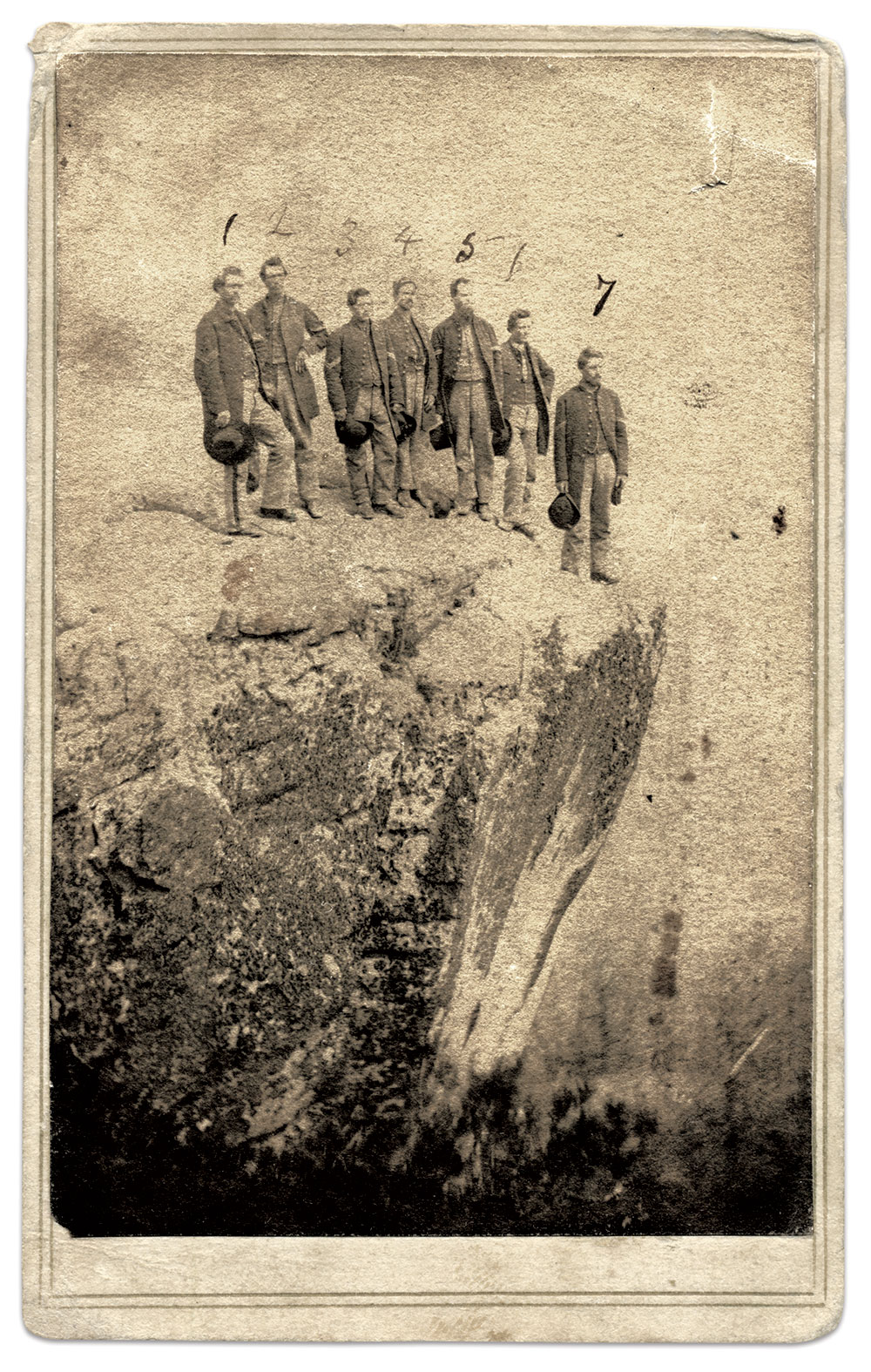

The 21st Wisconsin Infantry was stationed at the summit of Lookout Mountain following the Battle of Missionary Ridge through the spring of 1863. At some point, this group of seven enlisted men and non-commissioned officers from Company B posed at Point Lookout.

They are (1) Sgt. Edgar Vredenburg (1840-1914), who ended the war as first lieutenant of the company; (2) Cpl. Daniel Henderson Moscrip (1833-1915), who suffered a wound at the Battle of Buzzard’s Roost, Ga., and transferred into the Veteran Reserve Corps in December 1864; (3) Cpl. Frank E. Wickwire (1842-1934), who fell into enemy hands at Jefferson, Tenn., a day before the Battle of Stones River; (4) Pvt. Charles A. Peterson (1844-1926), who was listed as a prisoner of war on June 7, 1864, during the Atlanta Campaign; (5); his older brother Cpl. Alexander Peterson (1842-1929), who went on to become the company’s second lieutenant; (6) Pvt. Melville Angell (1840-1874), who suffered a wound during the Atlanta Campaign; and (7) Cpl. Leonard J. Miller (about 1834-1900, a Canadian native wounded in the Battle of Resaca, Ga., who ended the war as a sergeant.

The names of all seven are written in period ink on the back of the mount with corresponding numbers. Below their names is an eighth name, unnumbered: J.E. Stuart. This is likely 1st Lt. James Edwards Stuart (1841-1931), a Scottish immigrant who ended the war as captain of Company B. Stuart settled in Illinois, where he went on to serve as an officer in the 2nd Illinois Infantry during the Spanish-American War and the 11th Illinois Infantry as brigadier general during World War I, though he remained stateside.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.