By Ronald S. Coddington

What will become of us? What will become of our country?

Existential questions such as these span the arc of humanity. In times of strife and unrest, such questions carry a deeper sense of urgency.

One afternoon in January 1864, a group of citizen soldiers in an army hospital ward in York, Pa., raised these questions in a conversation. Five in number and all in their twenties, they came of age in a society divided by blinding ideologies, escalating violence and seething hate that cast ever-lengthening shadows across the land—and, finally, torn asunder by civil war.

As children, they were touched directly and indirectly by the rapid spread of industrialization driven by railroads, the rise of mass media fueled by telegraphy and other technologies, and the birth of photography. They learned about the heady quest for gold and riches in far-off California, and the systematic, federally enforced enslavement of a race.

In York, these five young men spoke openly about their shared experiences in camp, campaign and combat as only comrades can. The conversation intensified as they described the joys and sorrows of their hardscrabble lives before the war, for none could claim financial wealth. Yet, despite the tenor of times, all expressed hope that they might live to build a bright future for themselves and their families.

The realities of the crisis at hand tempered the happy thoughts. An order might arrive at any moment to break up their little band forever, possibly to never be reunited. Therefore, they hatched a plan: They would meet again at a future date, renew old acquaintances and find out where life’s journey had taken them.

Thus closed a memorable conversation—and opened a new chapter in their lives.

A flurry of activity followed as they fleshed out details of the reunion. Someone suggested they gather 10 years in the future, but the group determined they needed 20 years to become established. They proposed meeting dates of July 1, the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, through July 4, the nation’s birthday, and Niagara Falls as the destination. Perhaps most significantly, they agreed to expand the group to a round dozen, adding seven more comrades by unanimous vote.

They drafted formal language and printed an official document with the nameplate “Excelsior Resolutions.” This pact formalized their intention to meet on July 1-4, 1884, and to bring their wives if married. Moreover, that each would strive to be the best at their chosen occupation, to be of good character, and to sacrifice life, fortune and honor to defend the Constitution and perpetuate freedom. If death intervened, a provision would be made to notify the others of his demise.

Members signed the document—a solemn oath forever binding them to the terms of The Compact.

Band of brothers in York

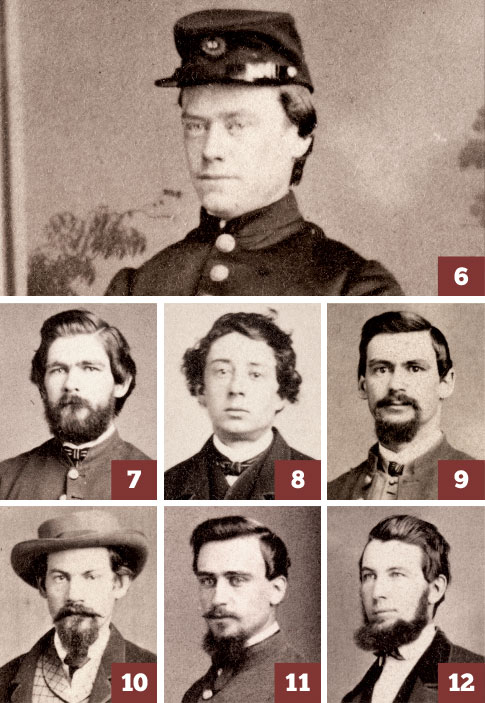

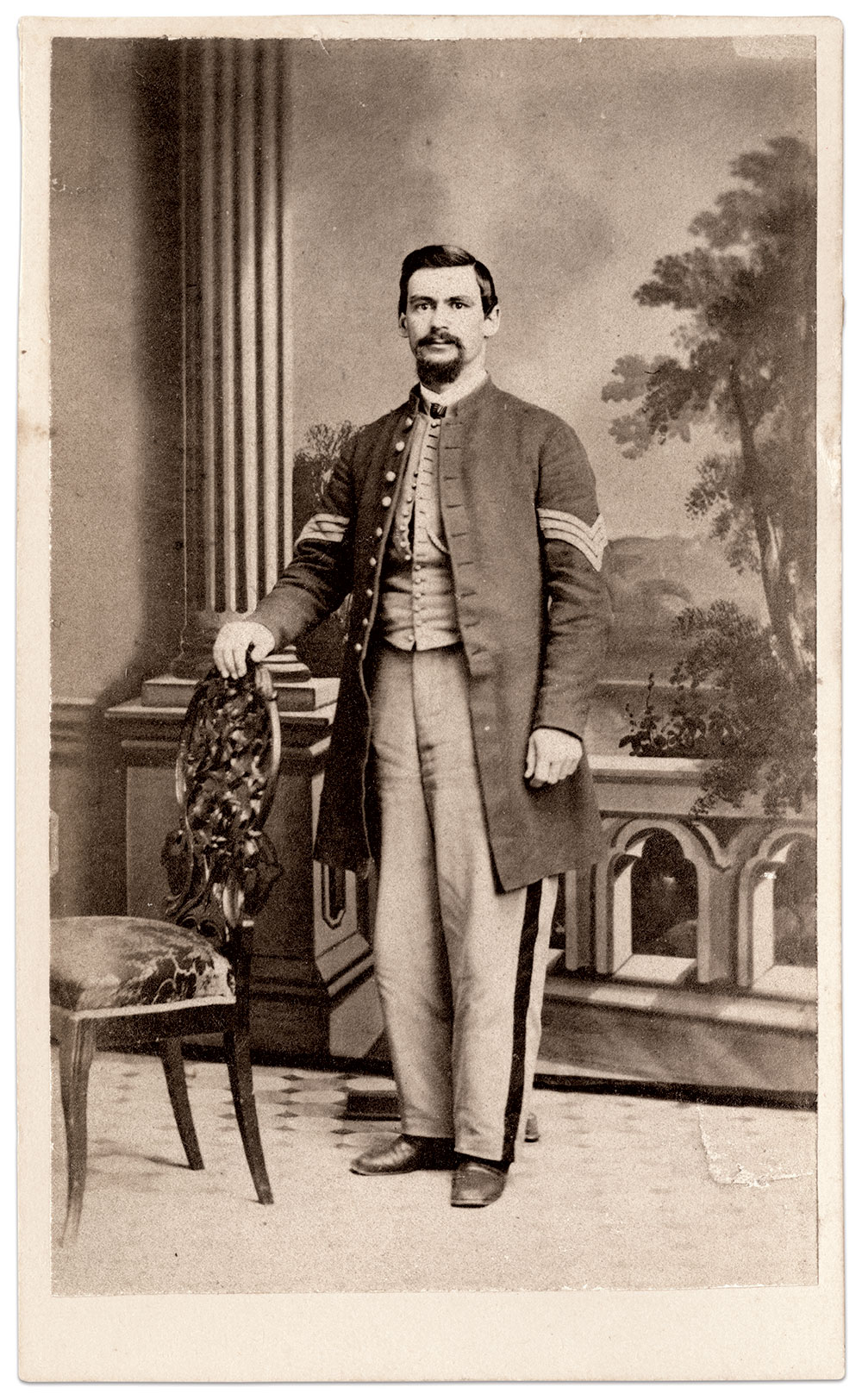

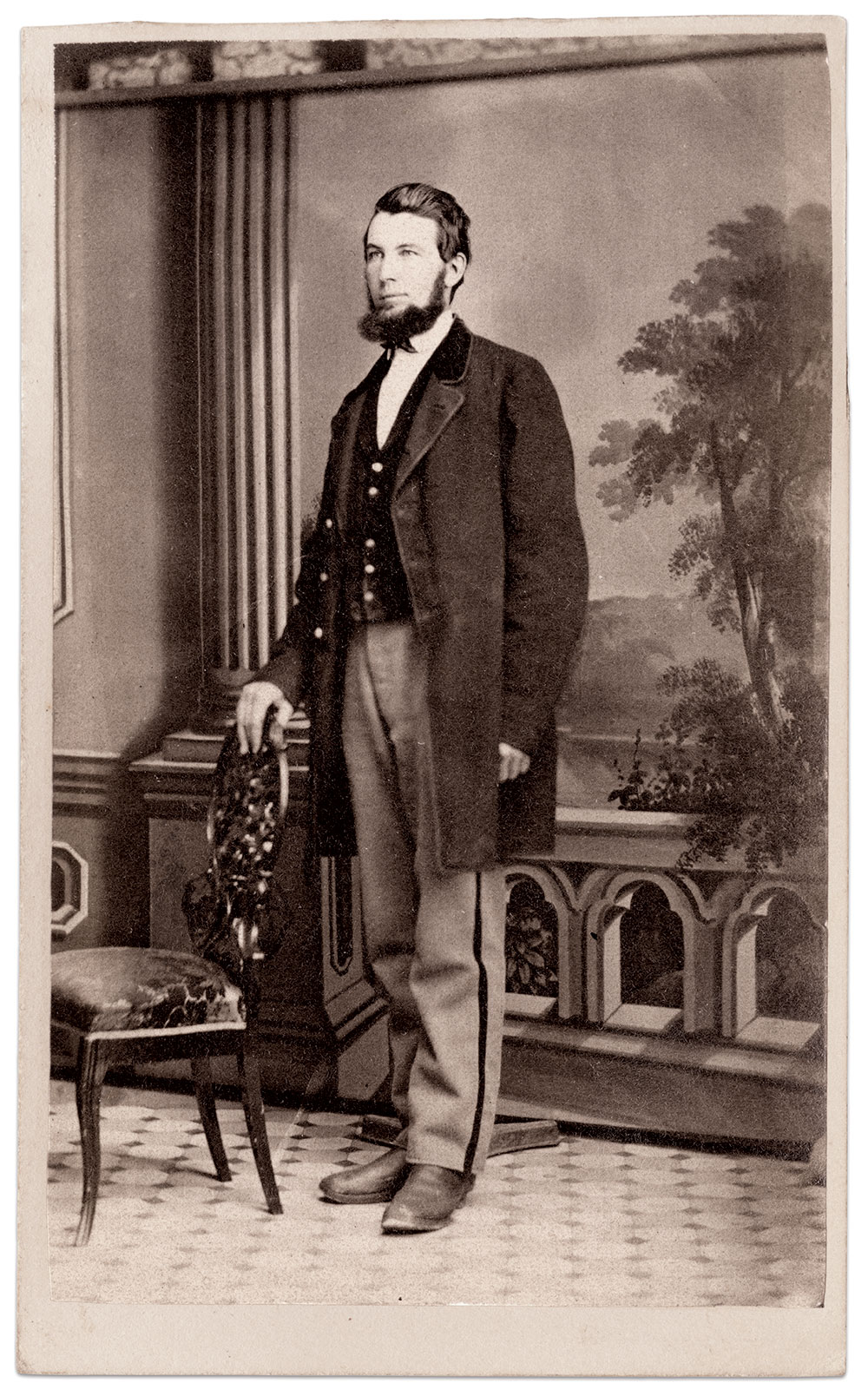

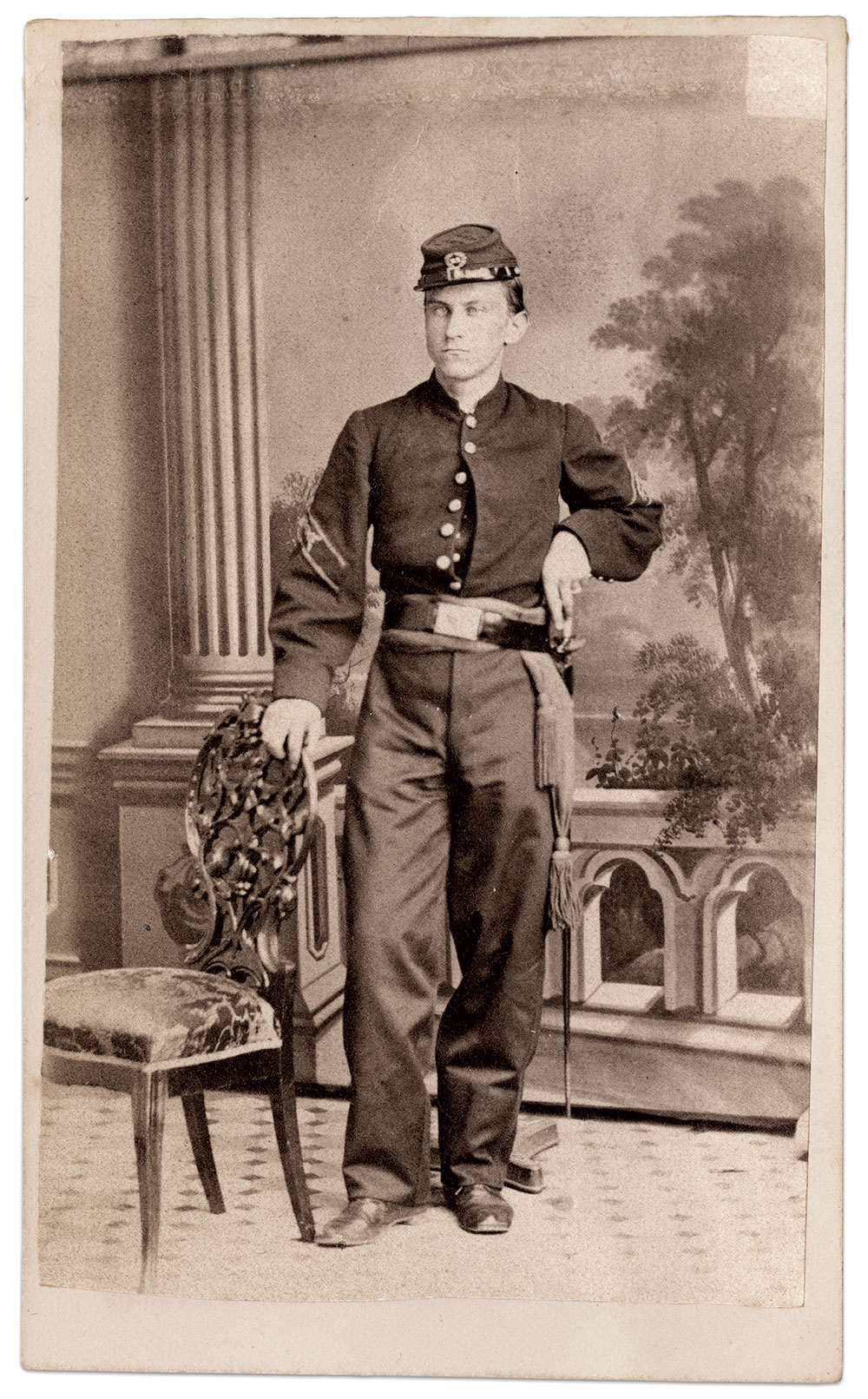

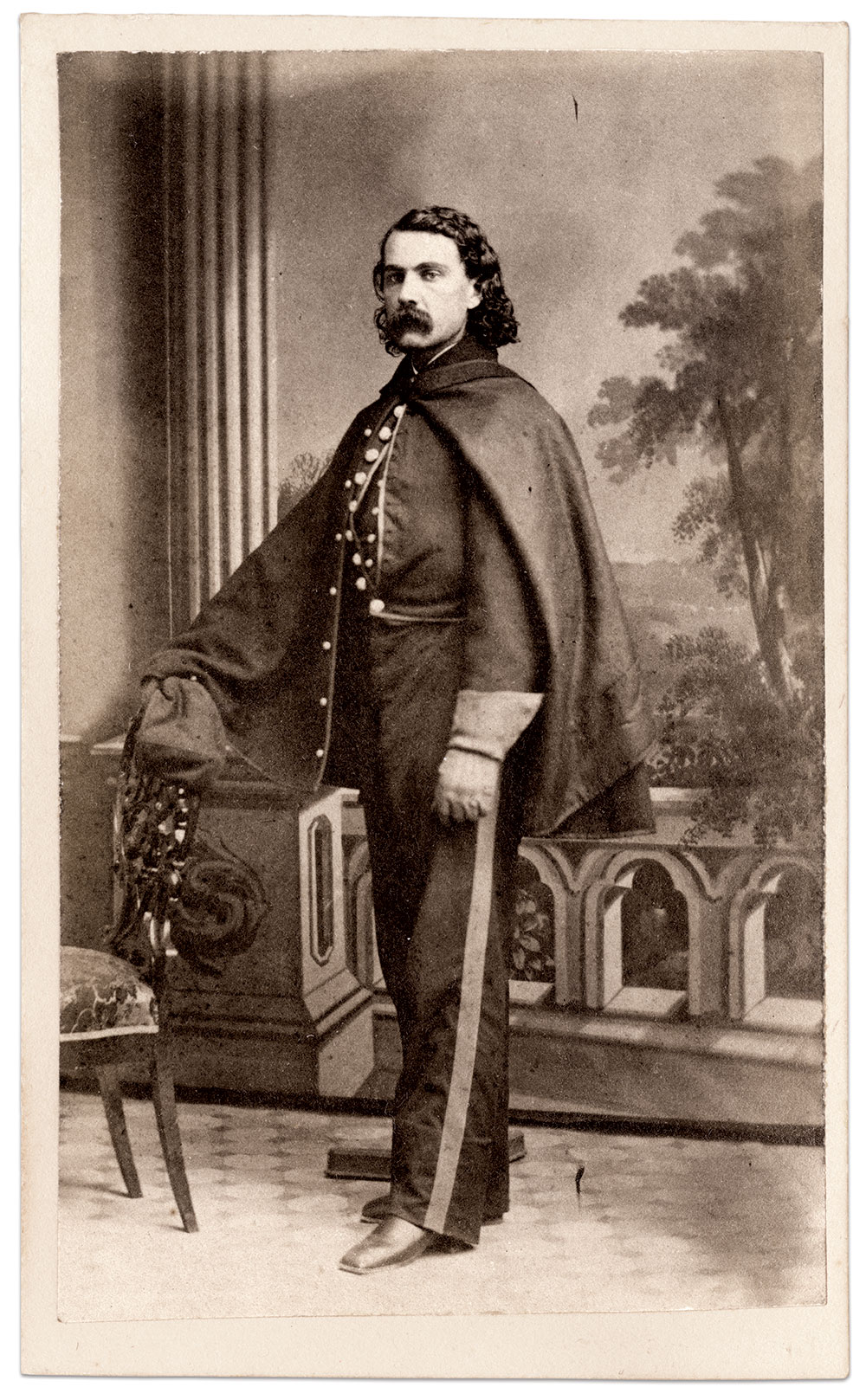

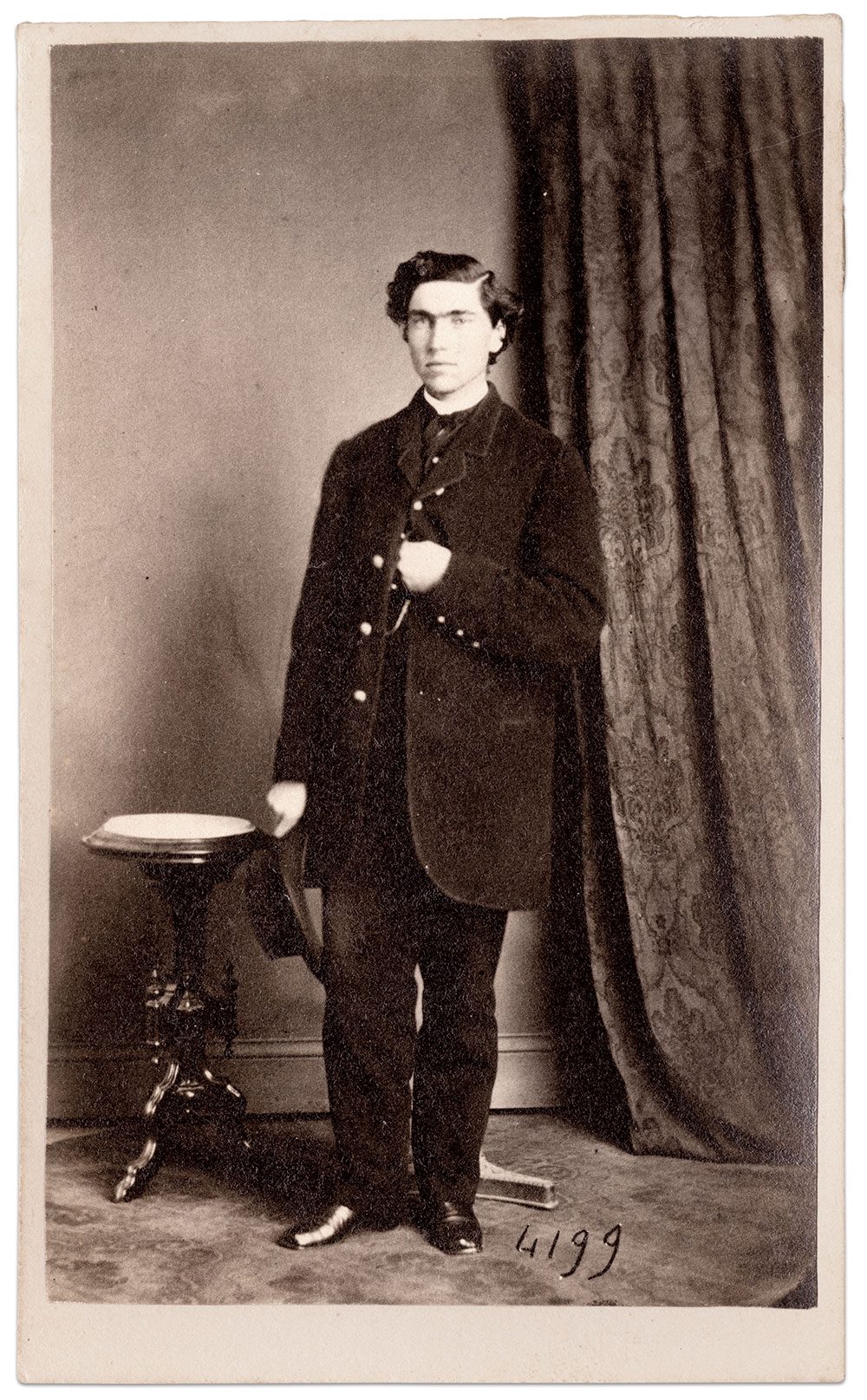

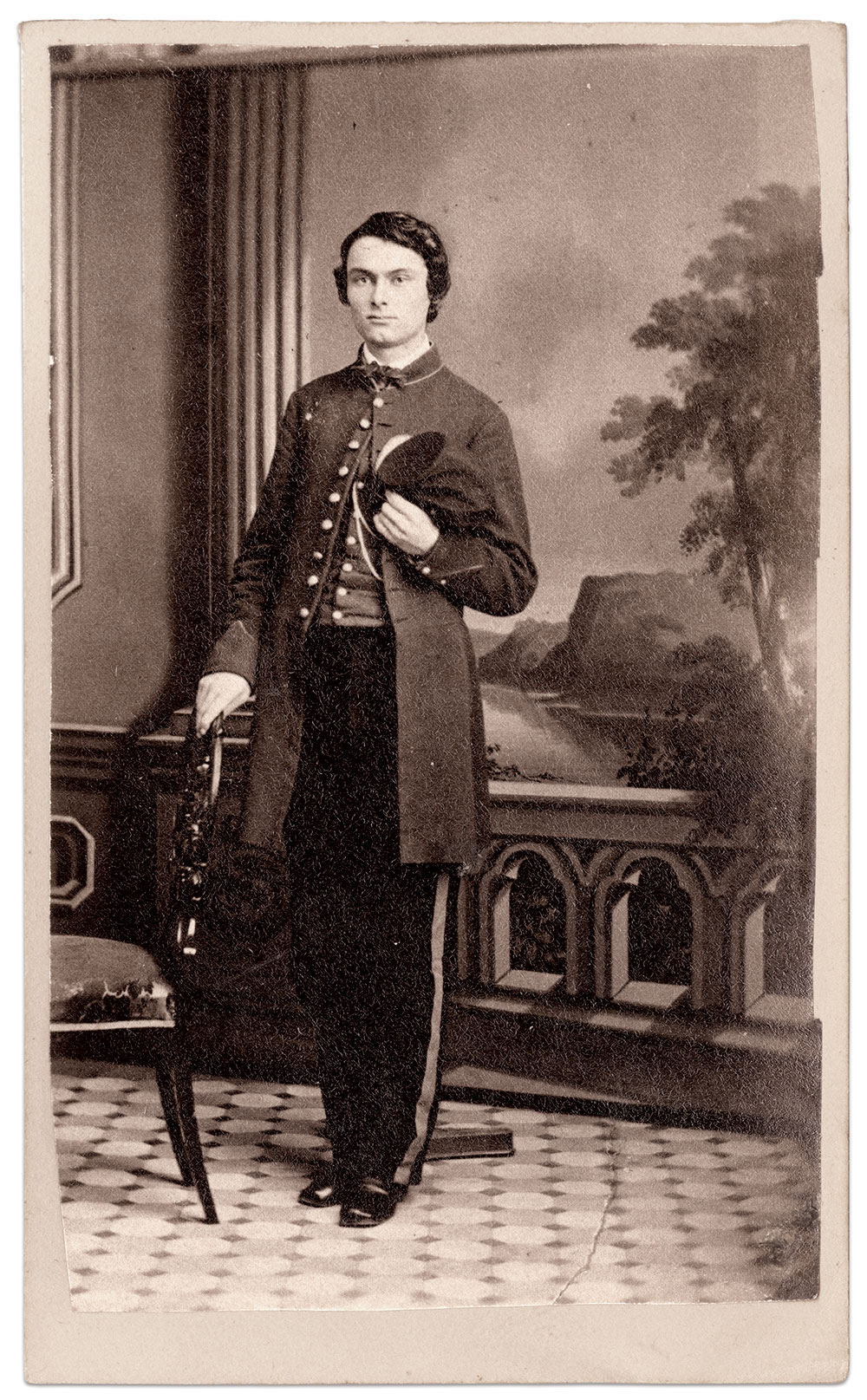

The dozen men are pictured here about this time signed the pledge. They represent six Union-loyal states, and served in the ranks or as non-commissioned officers. Three were hospital stewards. Four suffered wounds in battle. Six continued their service in the Veteran Reserve Corps, one went on to serve as a nurse, and two ended the war as infantry officers.

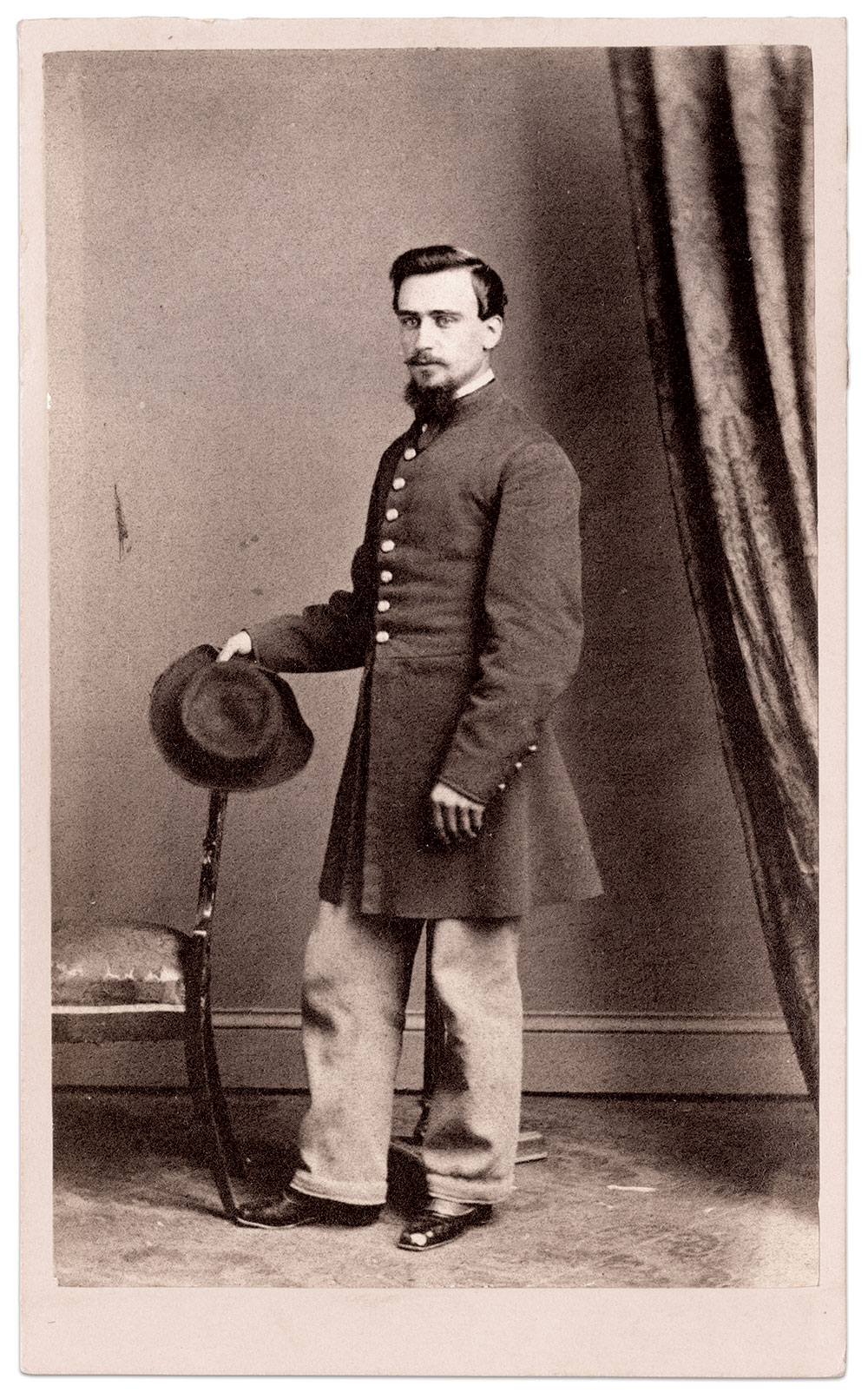

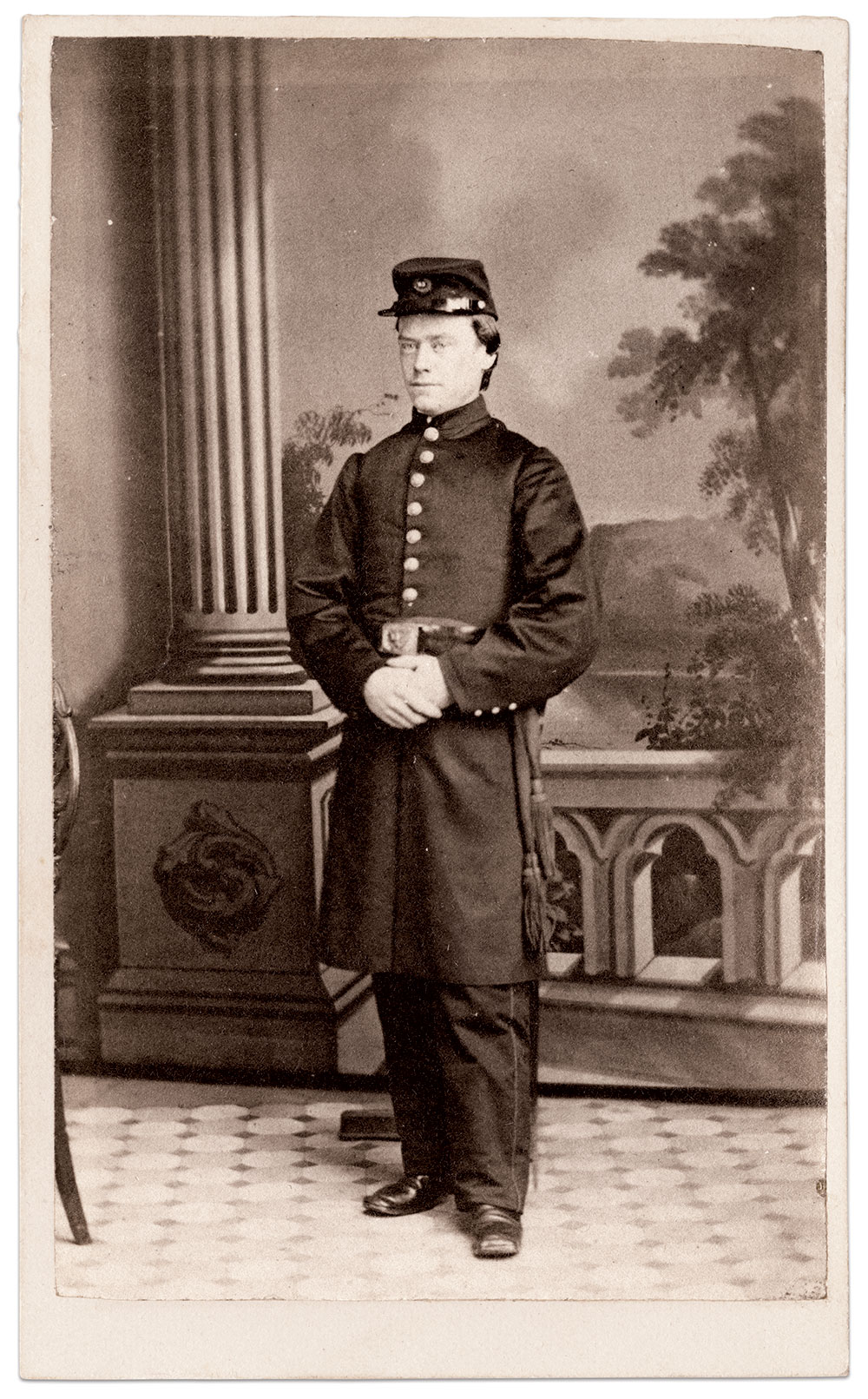

They posed for their portraits in downtown York at the gallery of Fitz James Evans (about 1835-before 1907) and David O. Prince (1825-1901). The partners operated a brisk business next to the post office. The images bear the Evans & Prince imprint on the back. The photographers offered at least two backdrops, one a painted background composed of a column and pedestal, balcony and nature scene that blends into the flooring, and another with a curtain draped along a faux wall finished with floorboard. The same ornate chair upholstered with a floral print is present in all the photographs.

The format of the photographs is noteworthy. The carte de visite, an albumen print made from a glass plate negative and pasted to a cardstock mount, was inexpensive, quickly reproduced, and easily shared. These card photographs normally sold by the dozen—the same number of soldiers who banded together and signed The Compact. One wonders if the popular paper print influenced the decision to expand the group to twelve. It also raises the possibility that 11 more sets of cartes de visite were produced, one for each man.

Five of the cartes de visite are dated on the verso between February 1 and 20, 1864—soon after they signed The Compact. The backs are also marked with small pencil numbers, 1-12, which correspond to the order of each in the frame’s mat, left to right and top to bottom row.

The numbers also match the order in which the men signed The Compact.

The order of the photos and the signatures on the document are not listed alphabetically, or by rank, age or another obvious categorization. It is reasonable to conclude that the organizing principle is that the first five participated in the original conversation and the remaining seven were voted in by the core group. If true, the numerals on the backs of the cartes effectively serve as roll numbers.

A common trait that connects the first group of five is leadership. John M. Johnston (#1) and Albert O. Cheney (#2) served as infantrymen in Pennsylvania and New York regiments, respectively, prior to joining the corps of hospital stewards with a rank equal to an ordnance sergeant. Both left their positions, and York, to become infantry officers. George W. Martin (#5), a private in the 50th New York Engineers, became a hospital steward during the summer of 1864. George Case (#4) of the 104th New York Infantry, who had regularly sent most of his soldier’s pay home to support his widowed mother and a sister, volunteered to write letters for his fellow patients. These four, all in their early twenties, were born within two years of each other. The fifth member, Coombs (#3), brought age and experience to the group. A sergeant about 28 years old, he was senior by at least six years to the other four. He had served as an orderly on the staff of Brig. Gen. Samuel S. Carroll, which provided him with a unique lens to view the war.

None of these five had married or suffered wounds in battle. Three of them landed in York as a result of illness: Coombs, Case and Martin.

The dominant characteristic of the second group is that six of seven were sick and wounded convalescents. Israel H. Hilles (#7) of the 3rd Maryland Infantry and William F. Eichar (#11) of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry fell ill during their enlistments. William H. Nelson (#8) of the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry suffered a wound and fell into enemy hands at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. Irving C. Hayes (#10) of the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry incurred an injury at the Battle of Second Bull Run in August 1862. Theodore D. Bahn (#9) of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry became a battle casualty at First Bull Run in 1861 and again at Gettysburg. Helim S. Thompson (#12) of the 44th New York Infantry also suffered a wound at Gettysburg. Hospital Steward William H. Ware (#6) was the only member of this group who could not claim to be hospitalized for his health. Ware also held the distinction of being the only married man of the dozen.

Though sidelined by illness and injury, the patients in this group continued to contribute to the war effort as soldiers. Five of them transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps.

Gettysburg Campaign connections

Three of the 12 soldiers could claim significant experiences directly related to the leadup to the engagement at Gettysburg or the battle itself.

Hospital Steward Cheney (#2) was on duty at the York hospital during the Confederate invasion of June 1863. Fears for the safety of the 500 patients prompted hospital staff to make secret preparations to move the men to safety. (The staff had made a similar move the previous September in the wake of the Confederate invasion that culminated in the Battle of Antietam.) They organized about 400 mobile patients into companies, and Cheney formed them into a battalion for exercise and drill. In late June, Cheney turned his attention to the remaining 100 convalescents who were unable to march, and organized their safe transport to Columbia, Pa. On June 28, 1863, as rebel forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Jubal Early approached York, another hospital staffer marched the battalion to nearby Wrightsville and out of harm’s way. Cheney returned to York after the Gettysburg fighting, and helped care for the 2,000 wounded soldiers transported from the battlefield for treatment.

Sgt. Bahn (#9) of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry marched into battle at Gettysburg on July 1 with a scar on his right shoulder at the base of the neck—a visible reminder of the gunshot he had received almost two years earlier at the First Battle of Bull Run. At Gettysburg, he suffered his second war wound during the first charge of the Iron Brigade. The bullet hit Bahn in the lower part of his right chest about 30 yards from where Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds met his end. Conscious though in agonizing pain, Bahn struggled into town and made his way to the Adams County Court House. The building had been converted into a makeshift hospital. Medical personnel forwarded him to York to recuperate.

Sergeant Thompson (#12) and his comrades in the 44th New York Infantry numbered among the troops rushed to the defense of Little Round Top on the second day. He suffered multiple wounds in this combat. One bullet struck him close to the right nostril and passed through his upper jaw before exiting the back of his head about two inches behind the right ear. Another bullet struck him in the left shoulder, and buckshot hit him in the knees and a thigh. Left for dead, a slight movement he made four hours later caught someone’s attention, and he was carried off the field and treated. Transported to the general hospital at York on July 30, his wounds were dressed by Hospital Steward Cheney. Thompson’s head wound left him with missing front teeth, paralysis of the right side of his face and deafness in the right ear.

York connections

Sprawling west from the Susquehanna River, York County is conveniently located near the Pennsylvania capital of Harrisburg, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, Md. During the Revolution and early British successes against the American rebels, the borough of York served as a temporary home to the Continental Congress. A county history published more than a century after the British surrender quoted Lafayette’s description of York as “the seat of the American Union in our most gloomy times.”

The proximity of York to major urban centers made it a natural location for a military hospital during the Civil War. In June 1862, temporary barracks erected on Penn Common for the 6th New York Cavalry during a recent assignment were expanded to establish a U.S. Army General Hospital, one in a network across the Northern states. Construction could not be completed soon enough, though, as escalating casualty lists required care facilities. In early July, just weeks after work began in York, an estimated 300 sick and wounded arrived.

Five of the signers gained admittance to the hospital during its first months of operation. Hospital Steward Johnston (#1) had started his military service as a private in the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry and fell sick at the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign in July. Private Nelson (#8) arrived in August after his release from a Confederate prison following his capture at Gaines’ Mill. Private Hayes (#10) entered the hospital after his wounding at Second Bull Run in late August. Second Sergeant Case (#4) contracted a severe cold after fighting in the Battle of Chantilly, Va., on September 1. Less than 10 days later, with his throat swollen so he could not speak, he was sent to York. Cheney (#2), a private in the 5th New York Infantry, popularly known as Duryée’s Zouaves, became a patient prior to November 1862, when he left the regiment to accept a hospital stewardship in the regular army.

One man was connected to the city by family ties. Sergeant Bahn (#9) had been born and raised in York County. He left at about age 15 after his mother died and he was sent live with an uncle in the West. He eventually made a home in Columbia County, Wis., from where he enlisted in his adopted state’s 2nd Infantry. He returned to Wisconsin after receiving a discharge in June 1864. In the 1870s, he returned to York County and went to work in the lumber and hardware business in Wrightsville. In 1880, Bahn entered into his own business as a milliner and prospered.

Two members found love and marriage in York.

Sergeant Coombs (#3) of the 1st Maine Cavalry met Isabella Gallagher during his stay at the hospital. They married and settled in York, where their daughter, Mary, was born in 1868.

Private Eichar (#11) left York after his discharge in late 1864, but was not gone for long. He returned the following year and married a local woman, Eliza B. Welty, and began a family. After Eliza’s death in 1879, Eichar remained in York, remarried, and started a second family. Eichar worked as a bookkeeper for an agricultural machinery manufacturer.

Planning for the 1884 reunion

Flash forward two decades. As the band of brothers had anticipated, life scattered them. Two of the men teamed up to fulfill the terms of The Compact. Cheney (#2) ended his service as a company captain in the 127th U.S. Colored Infantry. The regiment had participated in several engagements during the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox Campaign. He became a successful grocer in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., inventor of a butter and cheese tray, and a real estate broker. Martin (#5) remained at the York hospital through the war’s end. In 1866, he and his brother, Elbert, started a wholesale produce company in New York City. G.W. Martin & Bro. went on to become one of the nation’s largest providers of cream, butter and eggs. A prominent figure in the dairy world, he played a role in establishing the New York Mercantile Exchange to standardize the commodities marketplace.

Cheney and Martin likely connected through their business in the food industry. They declared themselves a committee and set about the work of tracking down the others. The pair likely had help from a third member of the group, Hilles (#7). A Quaker who had set aside his teachings to enlist, he ended his service as a sergeant in the Veteran Reserve Corps. After a stint with the Freedmen’s Bureau in Texas, Hilles returned to his native Pennsylvania, married, and settled in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he became Martin’s confidential secretary and bookkeeper.

Invitations were sent to the other nine members, addressed to the post offices in the towns each had listed when they signed The Compact. By this time, almost everyone had relocated to other places, and helpful postal clerks forwarded the communication when possible.

Six of the nine invitations landed in the hands of the intended recipients, and five were accepted. One member, Coombs (#3) sent his regrets. The war had compromised his health, and, suffering from paralysis and too ill to travel, he had taken up residence in a Soldiers’ Home.

The invitation sent to Case (#4) resulted in the news that he had barely survived the war, dying of consumption on April 16, 1865. He was about 24.

Two members never received or responded to the invitations. Presumed dead by Cheney and Martin, they in fact were very much alive.

Johnston (#1) had resigned as a hospital steward and left York in July 1864 to accept a second lieutenant’s commission in the 186th Pennsylvania Infantry. He spent the rest of the war in the defenses of nearby Philadelphia. After mustering out in 1865, Johnston made his way to California and became a grocer—the fourth member who made food a career.

Hospital Steward Ware (#6) continued to care for patients at the York hospital until the end of the war, when he continued his service in the Office of the Surgeon General in Washington, D.C. He resigned about 1866, and made his way west with his wife, Ophelia, and children, and established himself as a minister and temperance activist associated with the Good Templars. His travels took him to Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and North Dakota.

Despite the absences, eight members signed on for a reunion two decades in the making.

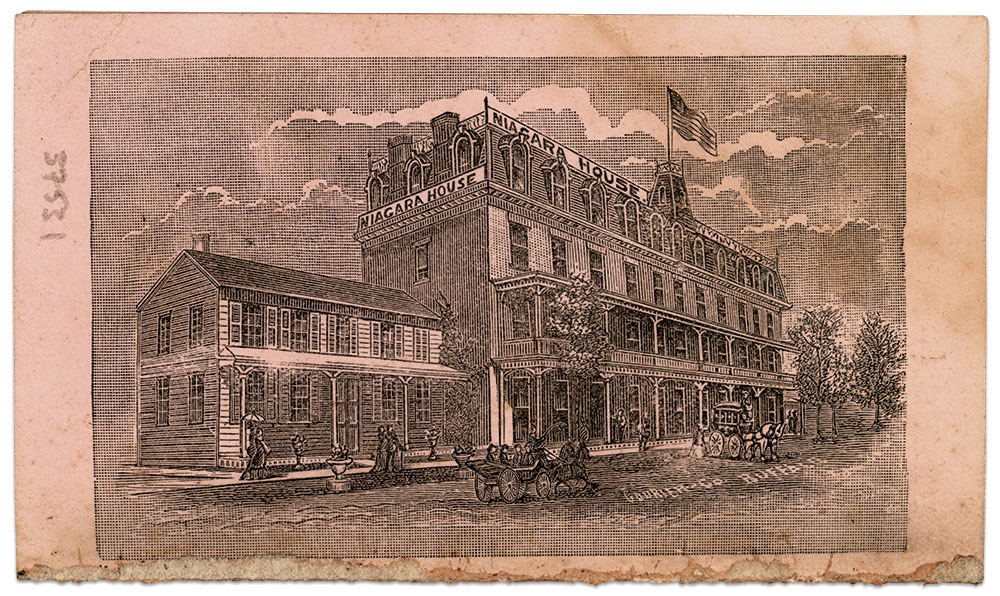

A gathering in Niagara Falls

Niagara House, an easy stroll to see the Falls and far enough away but still convenient to the railroad depot, attracted large numbers of tourists in the summer months. On Wednesday afternoon, July 2, 1884, eight graying veterans in their 40s, some with families in tow, gathered to become reacquainted and rekindle friendships.

News of the reunion attracted the press. A Niagara Falls Gazette reporter surveyed the group and observed, “All of the gentlemen present seemed to have enjoyed life reasonably well since the close of the war and possess a goodly share of this world’s goods.”

The group spent the next day taking in the views of Niagara Falls and other sights.

The main event of the reunion unfolded on Independence Day. Following traditional protocols, the veterans, joined by their families, arranged themselves in the hotel parlor at 10 a.m. Here, the eight members voted to establish a permanent reunion organization, dubbed the “Excelsior Association,” and elected Capt. Cheney as its Chairman, a fitting honor considering his role in organizing the reunion, his distinction of holding the lowest roll number present, and having held the highest military rank. They elected Hilles secretary of the association, a natural move considering his profession.

Hilles took minutes as Cheney called the meeting to order by expressing thanks to God for bringing them together. He turned to Thompson, the right side of his face noticeably affected by atrophied muscles from the gunshot at Little Round Top, to give the invocation. A reporter noted that Thompson thanked the Almighty “for His protecting care during the War and the blessings bestowed upon the little company since.” He also paused to honor absent comrades.

Cheney now produced The Compact, and Secretary Hilles read it aloud, resolution by resolution. Cheney then called the roll in the order of the signatures on the document. Each veteran in attendance responded in turn, announcing his name, address, occupation, and a summary of his life since the war.

A motion was made and passed for Chairman Cheney, Secretary Hilles and Martin to document the story of The Compact and recount the experiences of each soldier over the last 20 years in book form. They also decided to hold another reunion in five years, this time in York.

Celebratory toasts were offered, each revealing the state of mind of the giver.

Martin, the successful produce company owner: “The soldier as a business man, and secret of success in business.”

Secretary Hilles: “Comparison between the soldier and the civilian. The pen is mightier than the sword.”

Eichar, a current resident of York: “The old camp ground at York, and the people we met there.”

Hayes, who had been wounded at Second Bull Run: “Our dead comrades. Their names and deeds will never die.”

Nelson, the printer: “The Press. Its power is felt by rulers and warriors.”

Thompson, who had been left for dead on Little Round Top, “The absent members of our association. Their names are dear to our memory.”

Bahn, wounded on the first day at Gettysburg, prefaced his toast with an announcement that they would sing a tune sung every day in the hospital at York. Then he produced and passed around several sheets of paper—original copies of the lyrics from which they had performed the familiar song during those uncertain times in 1864: “Auld Lang Syne.”

A reporter described what happened next. “The members then looked upon the words with affection and rendered with a first-class vim.”

Cheney rounded out the toasts with one of his own: “The motto of our association—‘Our country, our whole country and nothing but our country.’”

The veterans and families then sung “America,” before adjourning to the hotel dining room to enjoy a banquet. Some of the veterans and their families left later in the day for home, and the rest on July 5.

Signers lost and artifacts found

The remarkable gathering of veterans at Niagara Falls turned out to be the first and only reunion. No evidence of the second event slated for York in 1889, or the proposed book about The Compact and its signers, has been found.

Chairman Cheney did visit York in 1903. He dropped by the offices of the York Daily, accompanied by Eichar, a well known and respected resident of the city that had toasted the old campground back in 1884. The pair reminisced about their wartime experiences at the hospital, which had closed about August 1865 after treating about 14,250 patients. Cheney mentioned a cache of 20 letters he had written home with descriptions of various scenes at the hospital and other York events. He also promised to write memoirs based on the letters and publish them in serial form in the York Daily. But no record exists that Cheney produced them before his death in 1911 at age 69. He had outlived seven of his comrades.

The 30-year period following the reunion is marked by the solemn, steady drumbeat of death thinning the ranks. Coombs, too ill to meetup in Niagara Falls, passed in 1891—the first to die since Case in 1865. Every few years, another comrade joined them: Ware, Hilles, Hayes, Thompson and Martin. Following Cheney was Bahn, Eichar, Johnston, and finally Nelson in 1922 at age 82.

It may be fairly stated that all of them lived up to the resolutions they agreed to in 1864.

On a late winter’s day in 1976, 110 years after The Compact came into existence, and a half-century since the death of its last signer, an American history professor at York College received a call. Dr. Carl E. Hatch listened as the man on the other end of the telephone, E.L. Ramsay, invited him to stop by his antique shop in York to see “a document that would fascinate me.”

Dr. Hatch shared his reaction in a story he wrote in York’s The Sunday News after seeing the paper in possession of Ramsay: “Fascinate me wasn’t the word for it!”

It was The Compact.

The professor announced to Sunday News readers that, “This is a gem of the first order—combining in it York’s relation to the Bicentennial; to the Civil War; to Veteran’s Day.” Dr. Hatch went on to provide a transcription of the resolutions and the names of the signers. Photographs of The Compact accompanied the story.

Today, the document resides in the archives of the York County History Center. It may be the actual version of The Compact carried to Niagara Falls and read aloud by Secretary Hilles to the assemblage. The later addition of Case’s death date is notable. No other copies are known to have survived, though it is easy to imagine that prints were made and given to each man to carry into civilian life—in effect, a “save the date” reminder for the 1884 reunion.

The original owner remains a mystery. The fact that it turned up in Ramsay’s antique shop points to one of three men with familial connections to York: Bahn, the York County native, or one of the two signers who married local women, Coombs and Eichar.

The original owner of the framed portraits is also a mystery. According to dealer and collector Paul J. Brzozowski, the artifact surfaced about 1999 at Braswell Galleries auction house in Norwalk, Conn. Brzozowski won the bid, and learned that Braswell’s had no provenance connected to the artifact. Braswell happened to be one of the largest auction houses in the Northeast at the time, which complicates efforts to pinpoint whether the lot came from a local source or some other place in the region.

Brzozowski sold the item to Jeff Kraus, owner of Jeffrey Kraus Antique Photographics, in 2018. The author acquired it from Kraus about this time, and had it professionally conserved by the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia.

Considering the mindset of the membership, it is reasonable to believe that they conceived of the framed portraits as a memorial to The Compact, and created it soon after the official signing in January 1864. If true, the likely candidate to inscribe the mat with their names and title is George Case, who volunteered to write letters for his fellow patients. Case prided himself on his penmanship. “I’m getting so as I can write a lady’s hand,” he boasted to his mother and sister in a letter dated May 19, 1864, from the York hospital.

An alternative theory to explain the framed prints is that the dozen cartes collected by one of the members soon after the signing of The Compact were originally contained in an album. At some point after the war, perhaps after the reunion, the owner removed the portraits from the album, and had them professionally framed or framed them himself. If true, it is likely that any one of the eight members, flush with enthusiasm after the Niagara Falls meeting, owned this unique keepsake in remembrance of an extraordinary Compact.

Special thanks to three individuals for their help with this project. Scott Mingus authored blog posts about Dr. Hatch’s report of the discovery of the parchment compact, news reports of the reunion, and the 1903 visit by Capt. Cheney to the offices of the York Daily. Scott also revealed the current location of the compact. Rachel Wetzel, currently a conservator at the Library of Congress, worked in a similar capacity at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in Philadelphia, Pa. Rachel expertly conserved the framed portrait grouping of the dozen signers. The CCAHA provided the digital scans published here. Adam Bentz of the York County History Center made the scan of The Compact available.

References: The York Daily, June 26, 1884; Niagara Falls Gazette, July 9, 1884; York Daily Record, June 14, 2009; Gibson, A History of York County; U.S. Census records; military service and pension records, National Archives; York Gazette, June 10 and July 8, 1862; Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, Buffalo, N.Y., July 4, 1884; Buffalo County Beacon, Gibbon, Neb., Aug. 1, 1884; York Daily, Dec. 3, 1903.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.