By Elizabeth A. Topping

The bloody conflict that raged in and around the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg for three days in early July 1863 resulted in 51,000 casualties. They included large numbers of wounded blue and gray soldiers scattered across miles of battlefield.

These souls had lain for hours or days awaiting rescue. Some had received treatment or surgery in the open, under a tree, inside a barn or in a local home. Surgeons left them behind on a dirt floor, a bed of straw or a hard door. Others fended for themselves as best they could.

The army erected makeshift field hospitals to accommodate them. These primitive facilities brought some relief to the dirty, thirsty, hungry and scared soldiers. Lady nurses arrived to alleviate the suffering. Their soft voices soothed frayed nerves, and their tender hands cleaned wounds and wiped brows. They gently changed soiled clothing and linens and administered nourishing food and drink. They wrote letters for those who could not and greeted family members who came to the hospitals searching for loved ones.

“Good God, how many thousands of those to whom we once ministered during our month sojourn are now sleeping in bloody graves, whose eternal silence the archangels trumpet alone can break.”

About three weeks after the battle, the Union Army of the Potomac’s Medical Corps merged the field hospitals. The Medical Director, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, established a general hospital. He selected George Wolf’s farm on York Pike, one-and-a-half miles east of town. Located on 80 acres of elevated and well-drained ground and bordered by a large grove of oak trees providing fresh air and cooling breezes, the site also benefitted by fresh water from a natural spring. A nearby railroad facilitated the movement of the wounded when well enough to travel.

By the end of July, some 4,000 soldiers, among them 1,300 Confederates, were relocated from the field facilities to the general hospital.

Camp Letterman, as the hospital came to be known, consisted of approximately 500 tents, each holding 12 to 14 cots with mattresses, sheets and pillows—welcomed luxuries for the patients. The grounds also contained a dead house, embalming tent, cemetery, cookhouse and warehouse tents. Guards watched over wounded Confederate prisoners and hospital supplies. Cooks, laundresses, chaplains and supply clerks joined the surgeons in hospital operations.

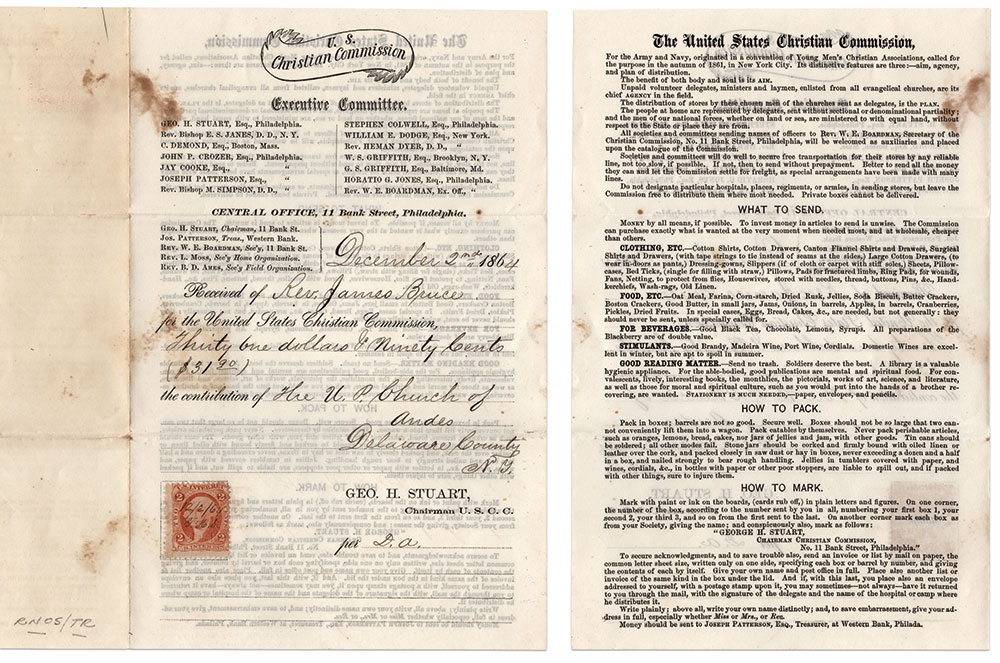

Camp Letterman also served as headquarters for two national philanthropies: The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) and the United States Christian Commission (USCC).

This albumen print pictures the USCC station at Camp Letterman at some point during its August to November existence. The camp had five tents for sleeping, eating and storage. Delegates and volunteers distributed food, clothing and medicines to federals and Confederates. They also tended to the religious needs of their patients, and encouraged them to not wait for death, but to come to terms with the life they would lead as disabled persons through the acceptance of Christ.

The ranking member of this group appears to be the pen-wielding, bearded gent wearing a light-colored hat and seated at a small desk covered in papers. He may be Mattias Willing, the New York minister who supervised the station.

The men in civilian clothes may be fellow delegates or volunteers. The soldiers are probably patients, their physical wounds hidden from view with the exception of the soldier leaning on crutches.

The ladies were likely volunteer nurses, as no women were employed by the USCC.

Though no ladies received official USCC Delegate credentials, dozens served informally. About 40 female nurses served at Camp Letterman from the Christian and Sanitary Commissions, including seven U.S. Army nurses. Every nurse visited patients nine times each day. Each nurse administered stimulants, distributed tea and special diets, and bathed and dressed 200 men.

Altogether, 400 men and women of all walks of life worked together at Camp Letterman without jealously or conflict for the benefit of their patients.

The USCC station and the rest of Camp Letterman remained in operation until Nov. 10, 1863. The hospital had cared for approximately 4,200 patients in its four-month existence. The tents were packed up. The remaining one hundred soldiers shipped home or to brick-and-mortar hospitals. And the doctors and nurses moved on to other battlefields. George Wolf reclaimed his farm, leaving only the cemetery untouched.

On Nov. 19, 1863, less than two weeks after the Camp ceased operations, President Abraham Lincoln and other dignitaries dedicated the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. A USCC relief agent in camp for 30 days, Jane Boswell Moore, described the scene in town on that auspicious day in Incidents at Gettysburg:

“Good God, how many thousands of those to whom we once ministered during our month sojourn are now sleeping in bloody graves, whose eternal silence the archangels trumpet alone can break. The photographs in Tyson’s gallery seemed to speak of those times. It is decorated with flags and gaily lighted, while the band plays beneath its windows, but the pictures on the wall bring before us Culps and Granite Hill, where the slaughter was most terrific, the almost impregnable summit of Round Top, with its rocky batteries, on which many an unburied form now reposes, the Headquarters of the General commanding on the Taneytown road pierced with screaming shells on that awful day.”

She added, “The plainest and smallest of houses through his kitchen windows we gazed to-day, and whose undaunted and forever illustrious tenant urged ‘every man to do his duty and leave the result to all wise Providence.’ History will record how nobly this pledge was redeemed; even should history be silent, the graves to be concerted to-morrow will be eloquent indeed.”

In 1864, the Union dead buried on George Wolf’s farm were removed to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Between 1872 and 1873, the remains of their Confederate brethren were relocated to Southern cemeteries. Today, the Camp Letterman site is home to a Giant Food supermarket on Highway 30.

References: Hoisington, ed., Gettysburg and the Christian Commission; Civil War Album, “Gettysburg, a Virtual Tour: ‘The Hospitals’”; Patriot Daughters of Lancaster, Hospital Scenes after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Elizabeth A. Topping has been a reenactor and living historian for more than 25 years. Her collection and research work focuses on the social and material history of the Civil War years. Her initial study centered on the subject of prostitution, which ultimately led to research on abortion, birth control and childbirth, female job opportunities and working conditions, medical treatment for poor and insane women, class and sex restrictions imposed on 19th-century females, the roles actresses played in society, and the parts women played in aiding the war efforts. Elizabeth enjoys sharing her expertise and artifacts for use in television programs, museums, magazines, conferences and roundtables.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.