By Adam Ochs Fletcher

I have sometimes found that knowing quite a lot about a backdrop is not all that helpful in better acquainting me with the subjects who stood before it. The majority of painted backdrops used during the Civil War were located where large confluences of soldiers gathered: such as at Benton Barracks in St. Louis, processing hubs like the Rendezvous of Distribution, and major cities. While knowledge of a backdrop’s location can be valuable, it doesn’t always reveal a subject’s regiment or home state. Many times, the backdrop is just banal evidence that the soldier was briefly present in a certain place.

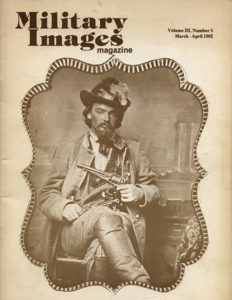

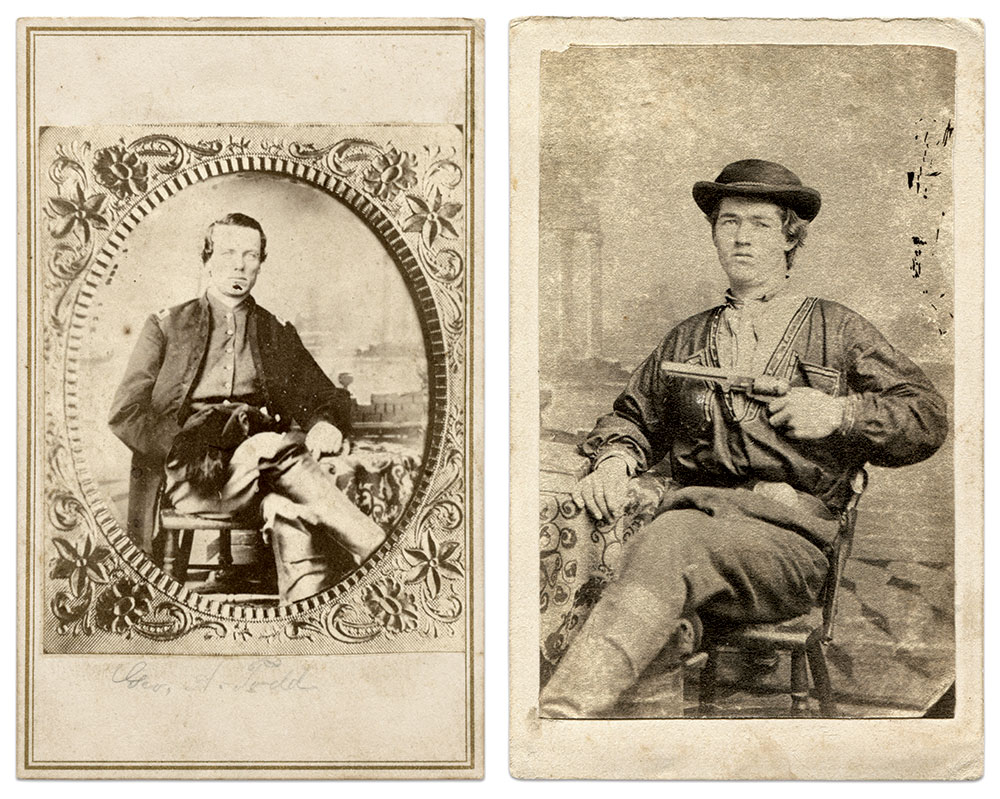

The example here is notable in that it conveys a wealth of contextual information. Though collectors have long recognized it as the backdrop used in certain images of Quantrill’s men, we can now definitively identify it as being located in Lexington, Mo., and used by photographer Thomas D. Saunders. Seemingly only used during the war by Saunders, the backdrop was situated in a tempest of sectarian violence that churned and billowed across the region.

Divided Missouri

In the border state of Missouri, few escaped the effects of the Civil War once hostilities began in 1861. In some parts of the country, the conflict was merely something read about in the morning newspaper. But in Missouri it saturated all facets of everyday life. It was the sound of galloping horses in the distance and of gunfire across town. It was the fear in the eyes of neighbors who no longer knew whom to trust, and of cannon fire that lit the night sky.

Factions divided Missouri. Citizens in the region contended with Unionists and Secessionists, pro-slavery “bushwhackers” and anti-slavery “Jayhawkers,” and various other partisan factions with competing aims and interests. These groups often fought without formal ties to the Union or Confederacy. While pro-Union officials ultimately prevented outright secession, Missouri descended into sectarian violence. Families took up arms against one another, divided by the expansion of slavery, the authority of the federal government, the legality of secession, and even how to pronounce the name of the state in which they resided.

Famous among the partisan guerrilla groups were “Quantrill’s Raiders” (as they were later known). Led by William Quantrill, the pro-slavery, pro-secession bushwhackers numbered less than 500 men formally affiliated with Confederate forces for a time. Quantrill and his men’s penchant for brutality prompted Southern officials to sever ties. The “Lawrence Massacre,” a retributive attack in which Quantrill’s men killed more than 150 men and boys in the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence, Kan., ended the relationship with the Confederate military. Quantrill’s Raiders and acts of violence they committed have long enthralled those interested in their exploits. Adding to the group’s almost myth-like status is the fact that a young Jesse James rode with Quantrill. James ranked among the last men loyal to Quantrill upon the latter’s demise in 1865.

Lexington: safe haven for Bushwhackers

At the outset of the war, Lexington, Mo., was a prosperous mid-sized town of around 4,000 located on the Missouri River. The seat of Lafayette County, it benefited from local agriculture, namely hemp and tobacco. Surrounded by large plantations, almost a third of the county’s population was enslaved. It is reasonable to assume that the planters and those who benefited from slavery contributed to Lexington’s reputation as sympathetic to the South. After the 1861 First Battle of Lexington, a Union defeat by Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s forces, Lexington became a safe haven for bushwhackers.

The Artist

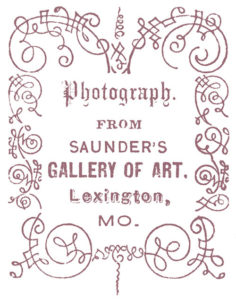

Thomas D. Saunders (sometimes spelled Sanders) was born in Kentucky in 1831, and ostensibly began operating as a daguerreotypist before age 29. His father, farmer and slaveholder Creed Saunders, died in Missouri in 1856. Perhaps finding the relatively small but wealthy town of Lexington suitable for a young photographer plying his trade, Saunders operated there as early as the 1850s. He appears in city business directories and tax lists as a photographist during the Civil War. Documents suggest the Union and Confederate armies conscripted him, though whether he served in either is unclear.

Thomas D. Saunders (sometimes spelled Sanders) was born in Kentucky in 1831, and ostensibly began operating as a daguerreotypist before age 29. His father, farmer and slaveholder Creed Saunders, died in Missouri in 1856. Perhaps finding the relatively small but wealthy town of Lexington suitable for a young photographer plying his trade, Saunders operated there as early as the 1850s. He appears in city business directories and tax lists as a photographist during the Civil War. Documents suggest the Union and Confederate armies conscripted him, though whether he served in either is unclear.

Advertisements for Saunders’ studio placed in newspapers several years after the war promote a world-class gallery rivaling the best in the country. It seems Saunders took special care in tinting his photos with color, according to his promotions. Saunders died in Kansas City in 1898. His obituary noted that he had only lived in that city for several years and was well known as a photographer in Lexington, where he had spent the bulk of his life.

The Backdrop

Saunders’ backdrop features a black and white diamond checkerboard style marble floor set before a large river embanked by hills in the distance. Atop those hills seem to be hazily rendered structures. On the water floats a sailboat, executed in a flat, simple style. In the foreground, to the left in the picture plane (when viewing a carte), stand the ruins of a Greek-style building distinguished by Doric columns at its entrance. In contrast to the time and circumstances, the scene inspires a peaceful harkening back to antiquity—though the ruins are apt!

Adam Ochs Fleischer is passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Chicago, Ill.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.