Fort Lamar, a roughly M-shaped earthwork bordered by swamps on each side, was a key strategic point for Confederate forces on James Island, S.C. If it fell into enemy hands, the fate of nearby Charleston and the rest of the Palmetto State would be seriously compromised.

Union forces made an attempt to take it at daylight on June 16, 1862. About 6,500 men in blue attacked the fort’s 2,000-man garrison. The federals gained a foothold on the causeway, but were stopped cold by a wide ditch, a 6-foot parapet topped by abattis, and the swamps.

Meanwhile, two Union regiments supporting the assault received orders to go in. One of them, the 97th Pennsylvania Infantry, rushed across scattered marshlands, open fields and through a deep swamp as rebel guns blasted away at them. Somehow, the Pennsylvanians maneuvered to within 200 yards of the fort without losing a man. From this position, they kept up a lively fire that prevented the garrison from using cannon on two sides.

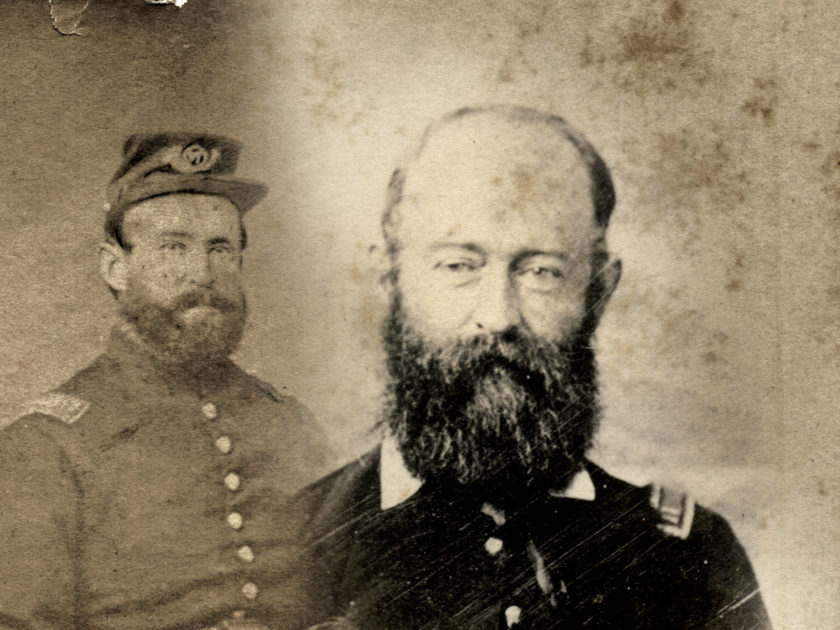

Confederate reinforcements soon made the position of the Keystone State men untenable and they withdrew. By this time, the tide had risen and the deep swamp between them and safety had swollen into a murky, oozing quagmire. Canister and round shot from the fort had stirred the mud into a mucky mess. The captain of Company F, 39-year-old Dewitt Clinton Lewis, recalled the trek: “After a severe struggle I landed on the far side from the enemy, as a matter of choice and necessity, assisting a number of comrades, whose heads were covered with mud, when their feet reached the bottom. I suppose they were dodging the canister. We were very good at that.”

Lewis continued, “I landed, tired, disgusted, and dreadfully covered with mud, and was trying to find out where I was located in the mass of filth, when I heard a faint call that sounded thick and muddy. Looking back over the ground and water, I saw a head pop up above the sticky mass about one-third of the way back.” Without hesitation, an exhausted Lewis stripped off his accouterments and plunged into the abyss during a storm of canister. Somehow, he made it to the sinking soldier and pulled him to the shore. The man belonged to Lewis’ company.

Lewis survived the swamp fight, which went down in history as the Battle of Secessionville. He mustered out in the fall of 1864 after a suffering a wound at Bermuda Hundred, Va. Lewis received brevet ranks of major and lieutenant colonel for gallantry.

In 1896, he added one more credit to his war service: The Medal of Honor, awarded for his selfless act of saving a soldier at Secessionville.

Active in regimental reunions, Lewis died in West Chester, Pa., three years later. His wife, Sarah, and two sons survived him.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.