By Paul Russinoff

Violent showers of rocks, coal, paving stones and occasional pistol shots intensified as the 62 gray uniformed men inside the battered Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Rail Road passenger car winced and clutched their muskets. Outside, a seething crowd massing from the streets of Baltimore surrounded the car shouting threats and obscenities. Inside, anger and trepidation consumed this first group of citizen soldiers, on their way to protect Washington and the new president with 10 rounds of ammunition in their cartridge boxes.

These soldiers, members of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry, had anticipated this moment. Hours earlier in Philadelphia, regimental command was told to expect rough treatment in Baltimore. In an attempt to prevent preemptory bloodshed, Col. Edward F. Jones issued clear orders: “You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused and perhaps assaulted, to which you must pay no attention whatsoever.” He added, “But if you are fired upon, and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire.”

Back inside the battered railcar, a pistol round finally penetrated the wall of the car and shot off a thumb. Despite searing pain, the wounded soldier held up his bloody hand triumphantly so the officers could see. As a result, the first order to fire during the American Civil War, where actual blood spilled, devolved to Maj. Benjamin Franklin Watson.

A few months before, the men inside and outside the railroad car were all American citizens, living under the same flag and the same laws. But in very short order things had changed dramatically. Whether you believed that an illegitimate leader, who did not even appear on the ballot in 10 states, was on the cusp of a violent dismantling of society, or whether you believed the government of the Founding Fathers was in immediate peril, threatened with an insurrection led by treasonous slaveholders, depended that day on which side of the railroad car one inhabited.

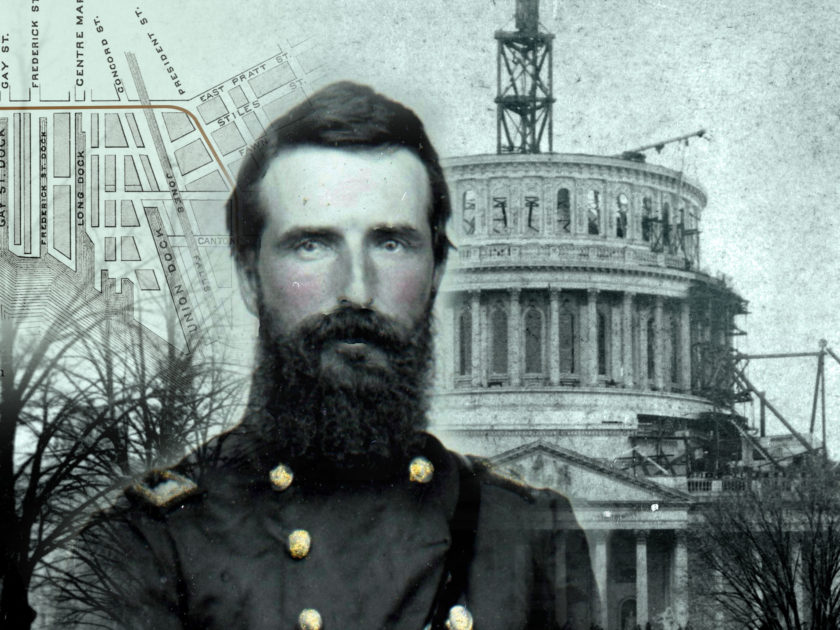

Four days earlier, April 15, 1861, had started out like any other for Maj. Watson and the men inside the passenger car. A prominent attorney, newspaper publisher and postmaster, Watson was a man on the move. He was born in Warner, N.H., in 1826, one of nine children to Cyrus Watson and Susan Evans Hall. By 1835, when Watson was nine, the family had relocated to Lowell, Mass. His father, a veteran of the War of 1812, died, leaving Susan to raise a large family. By the end of the 1840’s the family had moved again to Lawrence, Mass. Watson began his professional life as a bookseller and stationer according to an 1840 directory of Lawrence. By 1847, he began studying law in the office of Isaac M. Story in Boston. He gained admission to the bar in 1850—the same year he married Rebecca C. Dickey.

The study of law suited Watson particularly well. His memorial biography prepared by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion noted, “he was distinguished for superb intellectual gifts, to which he added the habit of infinite, careful minute painstaking [detail] and patience. His work was always so perfectly prepared…that he rarely lost a case.” Professionally and politically, Watson’s star rose steadily and substantially. An active Democrat, Watson received an appointment as Lawrence’s Postmaster from President Franklin Pierce in 1853. Four years later, Lawrence voters elected him City Solicitor. In addition to his law practice and his appointed and elected roles, he published the Lawrence Sentinel, the local Democratic newspaper. The Watsons financial fortunes followed his success, with a household valued at $13,600 ($425K in today’s dollars) and an Irish servant, according to the 1860 Census.

Like many men of his station, Watson joined the state militia and achieved the rank of major of the 6th Regiment, organized in 1855.

On Jan. 19, 1861, as the clouds of war loomed over the country, Democratic State Senator Benjamin F. Butler, who had started his own service as a private in the 6th and now ranked as a brigadier in the Bay State militia, made a suggestion to Maj. Watson. In the event of war, Butler reasoned, Watson should tender the service of the 6th for active duty to the newly elected governor, Republican John Andrew.

Though no supporter of the Republicans or President-elect Abraham Lincoln, Watson acted quickly. As a result, the 6th became one of the first militia units to officially offer their services to the Union.

Less than two months later, a shocked Boston learned of the firing on Fort Sumter, and the subsequent April 15 call by the president for 75,000 men to put down the rebellion.

About 4 p.m. on the 15th, counselor Watson was in court in the middle of a case when he was handed a note from Col. Jones activating the regiment. Two hours later, Watson had donned his uniform and occupied his time with assembling Lawrence’s two militia companies.

The assembly continued into the next day, April 16, bringing together 700 or so men and officers destined to muster in on Boston Common. Parallels with history buzzed through the ranks—86 years earlier, on April 19, 1775, minutemen fired on British soldier at nearby Lexington and Concord.

On April 17, three additional companies joined Watson and the rest of the 6th, making 11 in all, including the men of the Washington Light Guard from Boston, who would become Company K. At the State House, the troops exchanged antiquated smoothbores for rifled muskets, officers were presented with Colt Navy revolvers, and the regiment received its state colors by the governor. In his speech, Gov. Andrew began “Soldiers, summoned suddenly, with but a moment for preparation, we have done all that lay in the power of men to do, to prepare the citizen soldiers of Massachusetts for this service. We shall follow you with our benedictions, our benefactions, and prayers.”

With the official and unofficial ceremonies concluded by 7 p.m., the 6th took up the line of march and boarded a train to Washington at the Worcester Depot at sunset. Thousands of cheering citizens lined the track. Patriotic crowds, illuminated by bonfires, ushered on the train through Connecticut until it reached New York City early on the morning of the 18th. There, the Massachusetts soldiers encountered large and supportive demonstrations. By noon, the regiment was on its way again, through Jersey City, N.J., to Philadelphia.

Reaching the city at sunset on April 17, the 6th received a welcome with booming cannons and fireworks that dwarfed anything the men had so far witnessed. Accounts described crowds so intense that the regiment had to march by the flank to fit through the well-wishers, some literally emptying their pockets and showering money and gifts on the soldiers. The men marched to the newly constructed, and as yet unfurnished, Girard Hotel, for food and rest.

While the rank and file ate and slept, the officers dined at the Continental Hotel, where prominent Philadelphians personally waited on them.

A fellow Massachusetts man also present carried important intelligence. Phineas S. Davis, General of the Massachusetts State Militia, had been dispatched to Philadelphia in advance to scout the situation. In a confidential meeting with Col. Jones, Davis revealed that the reception in Baltimore would not only be hostile, but that the regiment could encounter violent, organized opposition.

Jones and Davis acted to minimize the threat. They met with S.M. Felton, president of the railroad, who agreed to dispatch an engine in advance of the troop train to discover any obstructions or sabotage of the track to Baltimore. Jones then decided an early arrival would be safest. At 1 a.m. in the morning of April 19, drummers beat the long roll and the sleepy men of the 6th marched through the now eerily empty Philadelphia streets to the train station. They boarded passenger cars by companies in a predetermined order and set out for an uncertain journey. As the train steamed through the night, ammunition was issued to the men, and Col. Jones gave specific orders about the terms of engagement.

Rail travel through Baltimore proved inconvenient in 1861. Officials forbade trains from passing through the city for fear embers from the locomotives would set fire to wooden structures. To avoid potential catastrophic events, southbound trains halted at the President Street Station on the north end of town. Here, cars were decoupled from their engines and drawn by teams of horses along a mile-and-a-half trolley track that ran the length of Pratt Street, the main thoroughfare. The horse-drawn cars stopped at Camden Street Station, the largest and most elaborate rail station in the U.S., where they were re-coupled to engines and sent on their way.

BRUTAL MILE-AND-A-HALF: Col. Jones, Maj. Watson and the rest of their command faced off with armed mobs along this stretch between President Street and Camden Street stations.

Jones opted to march through the city in regimental formation by companies, rather than take the horse-drawn cars. He planned to march between the two stations, and then board a Baltimore and Ohio train at the Camden Street station for the last leg of the trip to Washington.

One factor that Jones had not planned on occurred about 35 miles north of Baltimore, at Havre De Grace, Md. At this point, the broad Susquehanna River disrupted the route, so cars had to be ferried across and reassembled on the opposite side before continuing the journey. Unbeknownst to Watson and the other officers of the 6th, rail personnel reassembled the train in a somewhat random order, leaving the carefully planned regimental formation jumbled. The move would have a serious impact on the outcome of the day.

Though a mere hundred miles separates the City of Brotherly Love from Baltimore, the southern route traverses the Mason Dixon line, the major slave-owning divide, and now hostile territory. Watson recounted how, as the train approached the President Street Station around 10 a.m., “it was plain that some great excitement had stirred the people, for through the cross streets men could be seen, as we passed, running and gesticulating toward the train.” When the train arrived, the adjutant informed Maj. Watson that he was to join the car containing Company K, the last Company, and manage the rear of the march through Baltimore. As he walked the length of the train, looking for Company K, he was subjected to shouted threats by the gathering crowed, (and he noted, by certain policemen) that not one soldier would survive the march through the city.

Finding the car containing Company K, Watson located its captain, Walter S. Sampson, and told him about the rearguard assignment. Both officers discussed what might be expected from the crowd during their march. As they waited for orders to disembark and form up, their gaze turned from the men to the front of the car. To their surprise, the preceding rail cars containing what they believed to be the balance of the regiment had disappeared, and horses were now being hitched to the front of their car.

Thus began a violent journey through Baltimore, and into history.

The reason Jones’ plan failed was due to railroad officials in Baltimore, who desired to move the regiment through the city as quickly as possible. Cars containing the colonel and Companies A, B, E, F, G and H were hitched up to teams upon arrival at the station and hauled down Pratt Street—where they arrived at Camden Station without incident.

As these movements took place, mobs of pro-secession sympathizers and other anti-Union elements increased. By the time the car containing Company K was ready to depart, the mob had coalesced to a point where it could challenge its progress. A few hundred yards from President Street Station, where President Street and Pratt Street meet, the mob tossed an anchor from the nearby wharf on the track, as well as other obstructions, and derailed the car.

After a quick consultation with Capt. Sampson, Maj. Watson left the car, despite the gathering mob, and successfully enlisted a passing horse team to clear the track and place the car back on the rails. Watson climbed back inside the car and held the driver—whose loyalty was in doubt—at the point of his new Colt revolver. The car lurched forward.

The crowd let loose with rocks, paving stones and other missiles, shattering windows and splintering wooden sashes and the sides of the car. Watson remained in front with his gun trained on the driver, while Capt. Sampson ordered his men to keep down and avoid the shower of broken glass and rocks. Cuts and bruises began to take a toll on the men of Company K, who pleaded with Sampson to be allowed to fire into the crowd, but Watson would not allow it until they were fired upon and blood was drawn.

The distinct sound of pistol shots rang out, soon followed by the requisite injury—the thumb wound. The very one-sided affair was about to change.

Sampson instructed the soldiers to fire out the windows, and then shelter inside the car when reloading. Soon a steady hail of musket rounds poured into the crowd surrounding the railcar. Watson and Sampson headed to the middle of the car to examine the wounded soldier. At this point, they noticed the car had stopped and the driver and team were disappearing up Pratt Street.

Determining it would be safest to remain inside the car, as opposed to marching the men down Pratt, Watson again produced his revolver and took off after the driver and team. Meanwhile, Sampson observed that a rioter had jumped up on the front of the car and was addressing the crowd. The man then drew a pistol and gestured to the soldiers inside the car. Sampson ordered him shot down, and the man was killed.

Watson now returned with the terrified driver and his team, who hitched up his horses at gunpoint. The smashed railroad car, belching Minié balls and pummeled by a hail of paving stones and pistol shots, lurched a few more blocks up Pratt Street to the intersection of Howard Street. Here, the car could go no further because the mobs had torn up the track.

Fortunately, it was now only a short distance to Camden Station. The soldiers filed out of the car into the street, pushed through the hostile crowd and marched the short distance to safety, apparently without further casualties.

Once inside Camden Station, Watson and Company K were overjoyed to see their comrades, who were undoubtedly shocked at the condition of the bloodied and shaken men. Four of their number suffered gunshot wounds, and others nursed injuries from thrown rocks, wood splinters and broken glass.

It also became clear the remaining four companies and the band were cut off somewhere between the stations. Sampson volunteered to lead a rescue effort, but his command and Maj. Watson were ordered into the waiting cars bound for Washington.

A much more violent fate now awaited the 220 men in the remaining four companies. Their march through Baltimore was recounted many times in speeches, newspaper articles, books and other reminiscences.

Here’s how it happened.

The car carrying Maj. Watson, Capt. Sampson and Company K left President Street Station and soon crossed a partially constructed bridge over the Jones Falls Canal. The crowd then barricaded the track at this point, forcing the cars that followed to turn back the short distance to President Street Station. It became clear to the four company captains that the mile-and-half route would have to be marched on foot. They selected Capt. Albert S. Follansbee to command the detachment. He quickly enlisted a sympathetic Baltimore policeman to guide them to Camden Station. Before the march began, one of the mob members paraded a secessionist flag in front of the Massachusetts men. The emboldened rioters continued to taunt them after they started the march, waving the banner in front of the column. Others in the mob hurled rocks and other objects at them.

The four companies marched to the small bridge over Jones Falls canal and carefully picked their way over the scantlings. The crowd reacted to this breach of its barricade by firing pistols, in addition to a barrage of insults and rocks. Follansbee halted his command and, with Col. Jones’ rules of engagement clear in his mind, ordered the men to fire at will. The soldiers kept up the fire as they moved down Pratt Street, dragging their muskets between their legs as they reloaded.

Surging mobs overwhelmed the soldiers at different points, grabbing muskets and killing the first Massachusetts man, 17-year-old Luther Crawford Ladd of Company D. Each block produced new casualties on both sides.

Baltimore Mayor George W. Brown, apprised of the train’s arrival and alerted to the escalating situation, arrived on the scene. In a brave, but ultimately futile attempt to calm the situation, he joined Capt. Follansbee at the head of the column. Brown marched with the Massachusetts men for several hundred yards before the whipped-up masses became too dangerous.

More help arrived when the city’s Police Chief, Marshall Kane, appeared at Light and Charles streets with approximately 50 police officers. They formed a line with drawn pistols, establishing a barrier that effectively cut the mob off from the soldiers.

The men of these four companies—the last of the 6th on the streets—made the final trek to Camden Street Station and were welcomed by shocked officers and men.

At about 2 p.m., Col. Jones authorized the departure from Camden Station, urged on by frantic railroad officials convinced further delay would result in more bloodshed. As the train slowly departed, rioters attempted unsuccessfully to disrupt its progress towards Washington with several track obstructions.

Jones left behind the unarmed regimental band. Also stranded was an unarmed and ununiformed company of Pennsylvania militiamen. These men and the musicians left their instruments and various articles behind and disappeared into the city. No casualties were reported among this group.

However, the violence along Pratt Street resulted in a casualty list that amounted to four dead and 36 wounded Massachusetts men, and 12 dead citizens. Though these numbers would be eclipsed many times over in the months and years to come, the losses stunned the nation.

Black Americans and pro-Union men recovered the dead and rescued wounded soldiers sprawled on Pratt Street. They spirited one officer, Capt. John H. Dike of Company L, to a tavern. Believed dead at first, a tobacconist ultimately nursed him back to health.

Most of the dead and wounded ended up in the police station house, where an Episcopal Deaconess, Sister Adelaide Blanchard Tyler, herself a Bay Stater, interceded on their behalf. She had them transferred to her home, where they would receive medical care and ultimately rejoin their regiment.

A final civilian casualty, Robert Davis, lost his life about a half-mile outside Baltimore, when a soldier from the 6th shot him for shaking his fist at the slow-moving train.

The final stretch from Baltimore to Washington ended without incident about 6 p.m. on the evening of April 19. It also marked the conclusion of the 440-mile journey that had begun three days earlier in Boston.

The regiment arrived in a capital on edge. Effectively cut off from communications with the rest of the country, it faced a hostile Baltimore to the north and Virginia rebels to its immediate south. Some number of southern sympathizers lived inside the city. President Lincoln and military authorities expected an imminent attack.

The men and officers of the 6th were greeted by Maj. Irvin McDowell, and escorted to their new quarters in the Senate Chamber of the Capitol, its new dome under construction. Exhausted from the ordeal in Baltimore, the men slept on their arms. Col. Jones spent the night in the Vice President’s chair. The next day, and following days, the regiment spent much of its time employing construction equipment and materials to fortify the Capitol from assault.

On April 21, Maj. Watson made the short trip to the White House to meet with Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, seeking better rations for his men. They had been subsisting, as he later recalled, on “ancient” specimens of hard tack and “salt-horse.”

Upon his arrival at the Executive Mansion, Watson met Gen. Scott and made his request. The venerable Scott, presumably uniformed in full dress as was his custom, replied, “The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, sir shall have anything it wants.”

At this point, President Lincoln walked over and was introduced to Watson. The men shook hands. The president asked Watson if he would meet Baltimore’s Mayor Brown, who had come to Washington to plead with the President and Gen. Scott to send no more troops through his city and confirm the events of the 19th.

Watson consented. Writing many years later of the awkward encounter, Watson stated, “I fear my manner was not complimentary towards the Mayor. I am sure my speech was not…” and added, “that neither police, nor other officials had attempted any protection.” Watson did relay that Capt. Follansbee informed him that the mayor did march about 100 yards beside him, but left, saying that the position was “too hot.” Watson recalled the mayor looked disgusted but said nothing. Lincoln listened, and then turned to Watson, confirming that new rations would be forthcoming, and shook his hand again. The meeting concluded, and Watson departed.

Though the next three months paled in comparison to the regiment’s first 72 hours, there were moments of intrigue and activity. From its quarters in the Senate Chamber, the 6th drilled and paraded through the streets of Washington.

On at least one occasion, the regiment drilled in open columns in an attempt to make their numbers appear greater for the benefit of any secessionist spies among the bystanders.On May 5, as more troops trickled into the nation’s capital, the 6th moved north to guard the Relay House, a critical point in the rail network about six and half miles south of Baltimore. Once there, the rank-and-file elected Watson as their lieutenant colonel, and he assumed day-to-day command over the regiment.

On May 13, the 6th reported to Baltimore to occupy the city. Despite the discomfort of arriving in a driving rainstorm, the return to Baltimore must have elicited a sense of satisfaction among the men, who planted their flag on the newly constructed Fort Federal Hill, which overlooked the city.

A few days later, new orders sent the regiment back to the Relay House. Here, Lt. Col. Watson commanded a 50-man detachment that arrested Baltimore millionaire industrialist, state legislator and noted secessionist Ross Winans, who stood accused of amassing arms and materiel for the Confederate war effort, including a steam-powered cannon. Watson and his men nabbed Winans as he rode the train back from a meeting of the legislature in Frederick, Md. Authorities soon released the legislator on parole. His steam gun, now in possession of the Baltimore Police Department, was shelved as a toothless curiosity.

On May 25, the regiment drew up and saluted, as a train carrying the body of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth made its way north for burial. Ellsworth, the popular pre-war commander of the flashy U.S. Zouave Cadets, and a one-time law clerk to Lincoln, had suffered death in Alexandria, Va., after he hauled down a Confederate flag from a tavern. He had become a national martyr for the Union cause.

On this same day, several grateful citizens of the State of New Jersey presented the 6th with a new stand of colors. Watson accepted them on behalf of the regiment.

So ended the regiment’s first of its 3-month enlistment.

The final two months of its service involved brief excursions back and forth between the Relay House and Baltimore, a city now firmly under Union military control. The Fourth of July celebration involved the presentation of a magnificent silk banner from loyal citizens of Baltimore in commemoration of the regiment’s harrowing march on April 19.

During this time, the War Department reached out to Lt. Col. Watson to gauge his interest in commanding an independent regiment. Officials extended an invitation to Watson to meet with then Secretary of War Cameron, but he declined the command and the meeting.

The term of enlistment of the 6th expired on July 22, 1861. The day before, about 65 miles south of its camp in the vicinity of a stream called Bull Run, the first major clash of the war and the Union defeat that followed dismayed the North. Expected orders home were replaced by a request by Col. Jones to the men to remain in uniform for six more days. They agreed and received additional ammunition. It soon became apparent, however, that Confederate forces would not follow up on the victory, and the 6th prepared to return home.

On July 29, the men from Massachusetts broke camp and began to retrace their rail journey back to Boston. They did so with a Thanks of Congress, “for the alacrity with which they responded to the call of the President, and the patriotism and bravery which they displayed on the 19th of April last, in fighting their way through the city of Baltimore.” They also received a congratulatory note from grateful officials of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The first stop, a 5-hour layover in Baltimore, proved peaceful and cordial. Subsequent stops in Philadelphia and New York City drew throngs of patriotic citizens eager to glimpse the troops that had absorbed some of the first shock waves of the rebellion—and saved the Capitol.

On August 1, the troop train arrived at Worcester, where the men disembarked and marched into Boston. An official greeting by the mayor and quarters in Faneuil Hall for the night awaited them. The following day, they received another congratulatory order from Gov. Andrew, after which the companies left for their respective hometowns. Watson traveled with the Lawrence companies, and received a lavish welcome and parade that included the wife and sister of Cpl. Sumner Needham, one of the Baltimore fatalities. Both the mayor and Lt. Col. Watson made speeches.

The 6th had concluded one of the most memorable enlistments in the annals of American military history.

The lives of these Massachusetts men, and the hundreds of thousands who followed them, would be forever transformed. They left behind jobs, farm labor and family life to defend their nation. The bonds formed during their service carried on through their twilight years in the form of reunions and veterans’ associations.

The chaplain of the regiment, Rev. John W. Hanson, summed up their war experience with honesty and eloquence in Historical Sketch of the Old 6th Regiment.

“With the exception of the remarkable events of the 19th of April, the experience of the Sixth does not seem to have been very notable; but when the novelty of their position; the readiness with which they rushed to arms; the cool, calm courage they exhibited when surrounded by an infuriated mob; their obedience to orders, and their readiness to meet every emergency; the position of danger and importance they occupied at Washington, the first regiment to arrive for the defense of the capital; their efficiency at the Relay House and Baltimore, both at the beginning of the campaign, and their willingness to remain after their time had expired, when the disaster at Bull Run made their presence of the greatest importance; when all this is considered, crowded into the brief period of three months, it will be confessed by posterity, that theirs is a historic name and fame that should never be forgotten.”

Watson had proved his patriotism and dedication to the Union. He had no thirst, however, for battlefield glory. Upon returning home, he went on vacation to the seashore, and looked forward to returning to his civilian pursuits. But he was in store for an unexpected and unpleasant surprise. The postmastership of Lawrence, a lucrative political patronage job conferred on him by the two previous Democratic presidents was no longer his. Apparently, the mistaken assumption that Watson was recruiting a new regiment soon to be in the field, potentially exacerbated by his alignment with the Democrat party, had shifted the job to a Republican.

In fact, the announcement had been met with public resentment, for Watson had gained respect for his command of one of the Union’s more notable regiments. Now, it appeared, an administration desperately seeking unity and cooperation with pro-Union Democrats throughout the North was punishing him.

Once President Lincoln became aware of the situation, he requested his Postmaster General, Montgomery Blair, contact Watson. Blair’s communication, an invitation by the President to meet, found Watson during his seaside vacation.

Four weeks later, Watson arrived at the White House—his second visit to the mansion since the war began. Writing years later, Watson recounted Lincoln’s sincere apology and his earnest desire to make amends. Lincoln pressed him on what he could do to rectify this situation. Watson dismissed the possibility of field command or a civil appointment. Ultimately, Lincoln tendered him a commission as Paymaster of Volunteers with the rank of major, described by Watson as “one of the most desirable positions in the army.”

As the meeting wrapped up, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler was announced. Describing the encounter with his friend and former commander, Watson wrote, “In his peculiar manner the General scanned me from head to foot and demanded what had brought me there.” After Lincoln explained, Butler told Lincoln that Watson could serve as paymaster on his staff. “I left the President and General Butler together. That night I went with General Butler to visit the members of the Cabinet and heard the proposed expedition for the capture of New Orleans discussed in all its details. I subsequently accepted the Office.”

While politics certainly played a role in Lincoln’s outreach, his earnest desire to address a perceived wrong was unmistakable to Watson. His impression of the President was of “a man anxious, weary and heavy-laden, earnestly laboring to perform the duties laid upon him.”

Watson served as paymaster in Boston, Albany, N.Y., New York City, and finally at Fortress Monroe in Norfolk, Va. He resigned in September 1864 for unspecified health reasons. While never again commanding men under fire, he received a brevet rank of colonel of volunteers “for gallant and meritorious service.”

Back in Lawrence, Watson resumed his law practice. A few years later, he moved to New York City, joining the bar there in 1867, and established a successful law office. Following the death of wife, Rebecca, in 1882, Watson married his cousin, Mary McLanthan, 20 years his junior. Both marriages were childless. Watson became an active member of the Zions and St. Timothy Episcopal Church on West 57th Street, where he organized a Knights of Temperance Society, which strove to combat the evils of drink among young men in the city. However, he was most fondly remembered for his role as leader, historian and orator of the Society of Veterans of the “Brave Old Sixth.”

In 1870, nine years after their historic march through Baltimore, veterans of the 6th gathered in Worcester for a reunion that included a parade to the Rural Cemetery, where Col. Watson delivered a memorable speech later reprinted in pamphlet form. In addition to the oration, the pamphlet listed the business meeting of the society, where Watson was elected President, and which adopted a design for a membership badge and a membership certificate. The reunions, held for many years, usually consisted of a parade, an oration, a supper with toasts, and, of course, much camaraderie. Most were held in the Massachusetts towns that provided the companies, but occasionally also in Baltimore itself, and were actively reported in several newspapers.

In later years, Watson presided over a larger organization involving all the early war volunteers in the Bay State called the Association of Massachusetts Minute Men of ’61. As a historian of the 6th, Watson collected firsthand accounts from participants. In 1901, he published a monograph, including his oration, detailing the march through Baltimore, and essays on a number of related topics concerning the 6th and its role in history.

On Dec. 21, 1905, Watson passed away at age 79 at his Park Avenue home. His death made front-page news in Boston. His remains were carried to Lowell, where he had spent the most active and important years of his life and buried in the Lowell Cemetery under an impressive stone. His second wife, Mary, joined him there four years later in 1909.

By any standard, Col. Watson lived a successful and fulfilling life. He excelled in his profession, became an influential force in local politics, and was active in his church. But the four hours he spent in Baltimore as major of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry left a deep and lasting impression that consumed him for the rest of his days.

His memorial biography supports this conclusion: “Nothing pleased him more than to have with him some of his old comrades to dine and talk over the stirring times of ’61, and always had a kind word and helping hand to any of those who were in sickness or need. … His many friends will mourn his loss, but none will do so more deeply than the survivors of the ‘Old Sixth.’”

Special thanks to Deborah Barrett, wife of the late Arthur G. “Gil” Barrett, for her generosity in making several important images from their collection available for this story. Also, thanks to Ross J. Kelbaugh for making the scans of William R. Clark available from his 2012 book, Maryland’s Civil War Photographs: The Sesquicentennial Collection.

References: Hanson, Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers; Brown, Baltimore & The Nineteenth of April 1861; Sheads, Toomey, and Roebuck, Baltimore During the Civil War; Watson, Address, Reviews and Episodes Chiefly Concerning the “Old Sixth” Massachusetts Regiment; Wilson and Fisk, eds., Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography; MOLLUS, “In Memoriam, Benjamin Francis Watson,” Circular No. 17, Series of 1906; Hall, Regiments and Armories of Massachusetts: An Historical Narration of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, with Portraits and Biographies of Officers Past and Present; Coddington, Faces of Civil War Nurses; Chandler, The Chandler Family: The Descendants of William and Annis Chandler who settled in Roxbury, Mass., 1637; Kelbaugh, Maryland’s Civil War Photographs: The Sesquicentennial Collection.

Paul Russinoff of Baltimore has been a passionate collector and researcher of photographs from the Civil War since elementary school. A subscriber to MI since its inception, representative images from his collection appeared in the Autumn 2014 issue. He is a senior editor of MI.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more

1 thought on “A Savior of the Capitol”

Comments are closed.