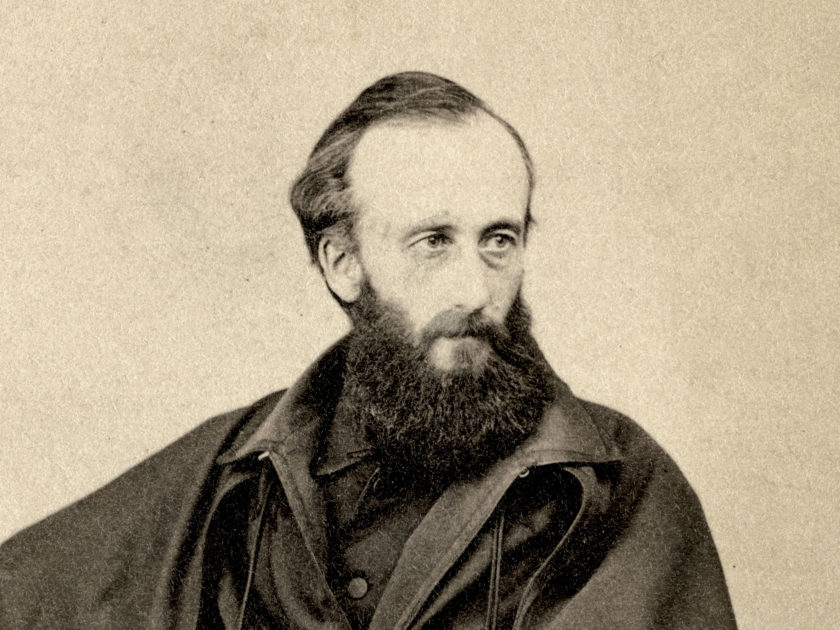

Chaplain John H. Frazee

By Joseph G. Bilby

When the troopers of the 3rd New Jersey Cavalry formed in early 1864, they were issued one of the Union army’s most flamboyant uniforms. Reminiscent of European Hussar cavalry, it featured yards of gold braid and orange piping and a peculiar if distinctive hat choice, apparently the standard kepi with bill removed and worn sideways.

One man in particular did not receive the distinctive uniform, the regiment’s chaplain, John H. Frazee. He’s pictured here dressed in the muted frock coat with cloth-covered buttons prescribed by the War Department in 1861. His elaborate overcoat was stylistically in spirit of the unconventional uniforms that earned his comrades the nickname “Butterflies.”

Frazee joined the 3rd in March 1864 after arranging a leave from his pastorship of the First Methodist Church of Toms River, located along the New Jersey coast. He had previously served with the American Home Missionary Society in Mississippi. Although not a combat leader, he accompanied the regimental headquarters in the field, where he oversaw the morals of the regiment. Frazee’s biggest challenge may have been his colonel, Andrew J. Morrison, a heavy drinker who designed the uniforms and insisted that his troopers be equipped with sabers as their only weapons. (Some revolvers were also issued.)

Morrison’s drinking led to his being relieved of duty with his first command, the 26th New Jersey Infantry, after he led it in the wrong direction during the 1863 Chancellorsville Campaign. Morrison appealed the decision on the grounds of his inexperience with the infantry, having had previously served as a mercenary in Europe with the cavalry. Somehow, Morrison was recommissioned, most likely due to political connections.

No evidence suggests that Frazee’s presence impacted Morrison’s drinking. The colonel’s alcohol-induced problems continued during his service with the 3rd, which was initially assigned as support for Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Ninth Corps, and later transferred to Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps.

The Butterflies fought numerous skirmishes during the 1864 advance to Richmond with Burnside, and later in the Shenandoah Valley with Sheridan. Along the way, Sheridan made sure the Jerseymen received more revolvers plus a hodgepodge of carbines, including Joslyn, Sharps and Burnside models.

In January 1865, Frazee resigned his chaplain’s commission out of concern for his family and church. Meanwhile, the 3rd moved down to Petersburg, and participated in the final campaign of the war in the East.

Frazee’s church reassigned him to a parish in Knoxville, Tenn., where he mixed with former Confederate veterans and commissioned artist Lloyd Branson to paint a portrait of another soldier who, like Morrison, fancied colorful uniforms—George A. Custer. The flaxen-haired general had given Frazee his carte de visite portrait in November 1864. It served as the basis for the portrait.

Frazee stayed active in the affairs of Union veterans as member of the Grand Army of the Republic, serving as chaplain of the Tennessee Department. He also served as chaplain of the Third Regiment of the Tennessee National Guard and a youth group, the Boys’ Brigade.

In 1904, Frazee declined an invitation to attend a reunion of the 3rd in New Jersey, due to distance and his responsibilities in Knoxville. According to a newspaper report, his letter of regret noted, “I would have loved to look in their faces and talk once more of the old days.”

Three years later, in 1907, he died at about age 69. His remains rest in Knoxville’s New Gray Cemetery, beside his wife, Caroline, who died a month before his passing.

Joseph G. Bilby is assistant Curator of the National Guard Militia Museum of New Jersey. He received BA and MA degrees from Seton Hall University and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Division in Vietnam. He is the author of numerous articles and books on New Jersey and military history and has received several awards for his work, including the Richard J. Hughes award from the New Jersey Historical Commission for his contributions to the state’s history.

Photographer Andrew Sims

By Gary D. Saretzky

There is no record of when Chaplain John H. Frazee sat for this portrait in the Camden, N.J., gallery of photographer Andrew Sims. The event likely occurred at the beginning or end of Frazee’s service—March 1864 or January 1865.

It may be stated with certainty that Sims was a recent immigrant who was at the beginning of a long career in photography that lasted into the 20th century.

Back in 1858, Sims purchased a one-way ticket to the United States from his native Scotland and settled in Camden, with his wife Mary and children. They ultimately had eleven sons and daughters, six of whom survived to maturity.

The 1860s was a period of adjustment for Sims as he found his way in American society.

The 1860s was a period of adjustment for Sims as he found his way in American society. He first supported his family as a gilder, a trade he may have practiced in Scotland. In 1863, when he registered for the military draft, he listed his occupation as a picture framer. By 1865, he had established a photograph gallery on Federal Street, just a few blocks from the banks of the Delaware River opposite Philadelphia. Sims also sold mirrors and picture frames—no doubt gilded by the proprietor. Considering the modest size of Camden at that time, about 17,000, it comes as no surprise that Sims was one of only two photographers in the city’s 1865 directory.

In addition to his photographic work, Sims became active in the Third Street Methodist Episcopal Church, and eventually became a trustee and a class teacher. By 1870, he was a member of the Board of Managers of the YMCA and a member of the Sparkling Water Division, No. 163, of the Sons of Temperance.

Sims relocated his gallery to various locations in Camden during his career, and in the late 1870s opened a branch gallery in Philadelphia at a studio formerly occupied by Daniel U. Snyder. Sims lasted in this location about a year, when photographer Lewis Horning succeeded him. Sims returned to Philadelphia in 1882 when he and his son, Leonard, who had been born in 1863, opened Sims and Son gallery. Another son, John, followed in his family’s footsteps and joined the Philadelphia gallery until his early death in 1890. The gallery continued to operate in Philadelphia until 1896.

The 1880 Census of Products of Industry for Camden provides insights into Sims’ work at that time. He had invested $2,500 in his business and had two male employees whom he paid $2.50 per day for skilled and $.82 per day for unskilled labor. Sims paid $1,040 in wages. During this period, his cost of materials was $320, and the value of his products, $2,180 (about $54,400 in 2020 dollars). His workday was 10 hours, and he remained open for business year-round.

Sims remained at his Camden location until 1885 but continued to be listed as a photographer at his home address in city directories until 1904. After this time, records suggest that Sims, now in his 70s, retired from photography and became a watchman. Leonard also left the business to become a bank messenger.

Sims lived until age 90, dying in 1917. He survived his wife by two years. Both are buried in Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery.

Gary D. Saretzky, archivist, educator, and photographer, worked as an archivist for more than fifty years at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Educational Testing Service, and the Monmouth County Archives. Saretzky taught at Mercer County Community College, and served as coordinator of the Public History Internship Program for Rutgers University. He has published more than 100 articles and reviews on various aspects of photography, including “Nineteenth-Century New Jersey Photographers,” in the journal, New Jersey History. Visit saretzky.com to learn more.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.