By James Bultema

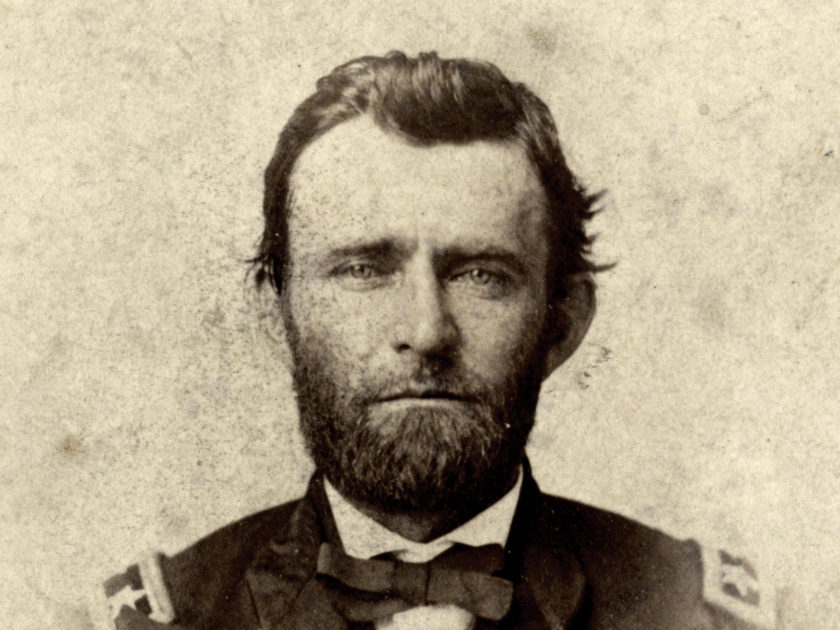

For collectors of images, playing detective by answering the “who, what, where, and when” in relation to one’s photograph, is very important in the process of assembling an identifiable group of views. I read with interest the fine article by Paul Russinoff, “Ock Tyner Leaves His Mark.” (MI, Winter 2020). What caught my attention was not only the photograph of Jesse Grant, but also that of his son, Ulysses S. Grant. There has been speculation as to when Grant sat for this series of photographs taken just after Vicksburg, and who took them. By tracking Grant’s movements after this important victory on July 4, 1863, and by examining the five known views, one can answer that question with reasonable confidence.

The summer of 1863 was a career-defining period for Grant, as he basked in the limelight after his brilliant victory at Vicksburg. Grant not only captured the Confederate bastion on the strategic Mississippi River, but also the adoration of the American people. Grant never felt more exhilarated. “Myself I feel younger than I did six years ago.”

Already popular from his early success in the Civil War, Grant’s fame sat at an all-time high. For people in the business of photography, this meant an opportunity to sell the general’s likeness to an ever-expanding market. It didn’t matter if Grant posed for them or someone else— shrewd photographers that never saw the general would get his image and sell it.

After Vicksburg, Grant did not want his Army to remain idle. He kept the pressure on the enemy by sending Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to chase the remaining Confederate forces from central Mississippi. On August 1, Grant asked his superior, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, for permission to visit New Orleans in his plan to take Mobile. On the 23rd, Grant was in Cairo, Ill., having accompanied his wife, Julia Dent Grant, on her trip to St. Louis. On the 26th, he was in Memphis; 27th in Helena, Ark.; then back to Vicksburg on the 31st. He left for New Orleans, arriving on Sept. 1.

The often-published portraits of Ulysses S. Grant picturing him as the conquerer of Vicksburg were actually taken in New Orleans two months after the siege ended.

Three days later, Gen. Grant was thrown from his horse and severely injured. For 10 days he laid in bed and did not write or correspond with anyone. This was highly unusual. On Sept. 15, finally feeling strong enough to ride back to Vicksburg, the general stopped in Theodore Lilienthal’s photographic studio at 102 Poydras Street in New Orleans for this series of images. From that sitting, one of those images appeared in the article by Russinoff, with a Barr & Young imprint; one of at least five taken that day.

Of the five views, only Lilienthal’s has an “Entered according to act of Congress” copyright dated “15th September 1863,” which corresponds exactly to Grant’s travels. The next day, he was back in Vicksburg. After his arrival, Grant wrote to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, his commanding officer, “I have returned from New Orleans, arriving here on the 16th inst. and am still confined to my bed, lying flat on my back—my injuries are severe, but still not dangerous. My recovery is simply a matter of time.”

Why did Lilienthal take the time to copyright his work? In his article entitled, “Entered According to Act of Congress,” (MI, Winter 2020) author Jason Lee Guthrie states clearly:

“Beyond legal protection, registering a work for copyright carries a certain cache of legitimacy, both for the work itself and for its creator. Copyright litigation is expensive and time consuming; printing a copyright claim on an image is not. Mid-19th century photographers were aware of rampant piracy, and most participated in it. If the printing of a copyright notice dissuaded even one potential pirate, it was worth the ink to print it. And when it came to the point, if copyright was not able to discourage piracy, at least the photographer’s name would be imprinted next to the image.”

One cannot assume that because the five images look similar, that they were taken the same day. It is important to insure they were. With this series, several identifiers are present that allows one to say they were taken the same day, and by inference, by the same photographer. For these images, the most obvious shows Grant had some hair sticking out of place, just behind his left ear, noticeable in all the views. His uniform appears the same, especially with the material curling at the tips on both sides of his uniform coat that is unbuttoned in all the views. His tie appears situated the same. For those images that look very similar, one must look at the position of his hands and how they differ in these views. Consequently, one can say, with near certainty, that this group of photographs were taken the same day. This author has seen this group with many different backmarks. The one by Lilienthal bears the copyright date of Sept. 15th, with Grant looking straight into the camera. It is puzzling that this author has not located any other views from this sitting with the Lilienthal imprints, merely the one with Grant looking straight into the camera.

The collective evidence suggests that Lilienthal took this series of views, and added a copyright date to the one that corresponds with Grant’s exact travel dates. The other views were pirated to take advantage of Grant’s popularity after the Vicksburg campaign. Russinoff’s article mentions that “Tyner inscribed this view (Grant) as made in September 1863,” which is correct. The one he mentions that resides at the New York Public Library with Barr & Young imprint was dated in August 1863. I believe this date incorrect. Nevertheless, we both agree that this series of Grant photographs taken after his success at Vicksburg helped catapult Grant onto the national stage—and eventually into the White House.

Five known poses of Grant from his sitting on Sept. 15, 1863

References: The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant; The Bultema-Williams Collection of Photographs and Prints, The Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State University; Heritage Auctions; Military Images, Winter 2020, pages 58 and 74.

James Bultema is the Vice-President of the Ulysses S. Grant Association and is currently writing Captured: A Photographic History of Ulysses S. Grant, which will be published by Southern Illinois University Press (2021). He has collected Grant images since the 1970s. The voluminous collection now resides at Mississippi State University in the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library. Prior work includes several books dealing with law enforcement history.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.