By Robert Marcus

During the years following the Civil War, American audiences packed venues across the country to experience the late conflict through images. Photographs of battlefields, camps, soldiers and statesmen combined with illustrations of poignant scenes to tell the story that restored and redefined the nation.

The device that made it all possible, the Magic Lantern, projected glass-plate images upon a screen, light-colored canvas or wall. Its impact on popular culture proved enormous. This was cinema before the innovation of the movies. Large audiences enjoyed travelogues, religious presentations, scientific lectures, works of art, history and other topics of wide public interest. They gathered in theaters, churches, opera houses, fraternal lodges, veterans’ halls, schoolhouses and even a convent. As many as 60,000 traveling Magic Lantern lectures took place at the height of its popularity.

The projectors were relatively simple. The technology had changed little since their introduction a century earlier. They utilized a variety of fuels: Oil, gases, denatured alcohol and a greenish calcium light then known as limelight. The last-named source is the origin of “in the limelight.” Magic Lanterns produced towards the end of the 19th century were electric powered.

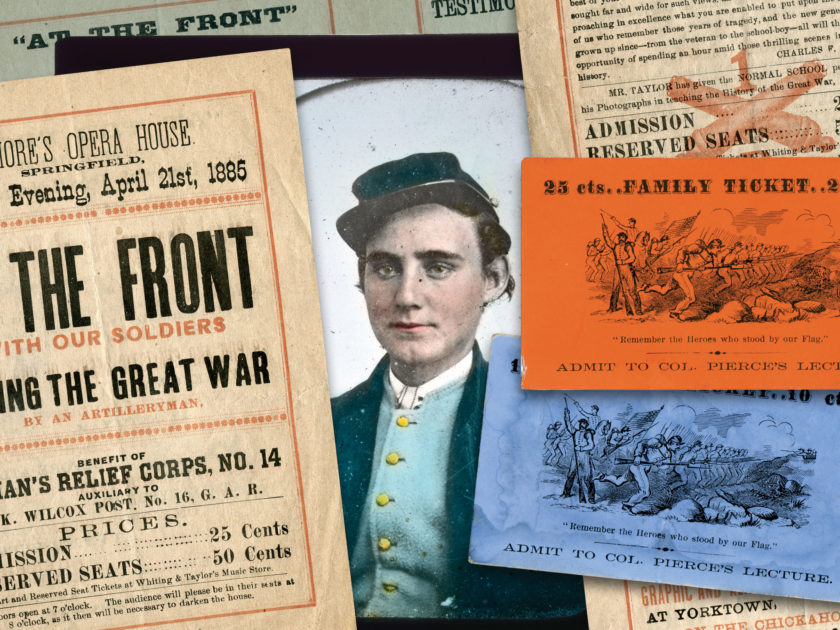

Manufacturers and purveyors of the Magic Lantern sold the technology as a do-it-yourself business and marketing kit. In addition to the projector, buyers received cases of glass slides, preprinted advertising broadsides, tickets, scripts, technical instructions and advice to maximize ticket sales. Marketing suggestions included the enlistment of pretty young girls to sell advance tickets, and boys to travel the streets and loudly hawk upcoming shows. A silver dime would gain a person admission to an event. A quarter allowed an entire family to enjoy the show.

Civil War veterans and lecturers numbered among those who bought into the business. They purchased custom Magic Lantern programs geared to the war.

The projections that mesmerized audiences were transparent photographs, engravings or woodcut illustrations on glass, in black and white or hand-colored. The clarity of these images compares favorably to all photographic technologies that have evolved up to the present day.

The photographic images include the finest work of the great Civil War photographers, including Mathew B. Brady, Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan. The woodcut illustrations, engravings and paintings encompass the work of the greatest American artists of the era, among them Winslow Homer and Thomas Nast.

The premier artist of Magic Lantern illustrations, however, was Joseph Boggs Beale, a native Philadelphian who earned the sobriquet “The Professor.” Beale had served in the ranks of the 33rd Pennsylvania Infantry, one of the Keystone State’s emergency militia regiments formed during the Confederate invasion of 1863 that culminated with the Battle of Gettysburg. Additionally, he illustrated war scenes as a soldier-artist.

Beale’s artwork appeared in the foremost-illustrated newspapers in the years following the war. He also produced about 2,000 illustrations exclusively for the Magic Lantern. Though they encompassed many genres—novels, Bible stories, plays, historical events, fraternal and temperance—his Civil War illustrations enjoyed particular renown.

Some of the best-known examples of Beale’s Civil War art are included here. One image pictures 95-year-old Barbara Fritchie taunting Confederate troops below her window, while waving the Union banner in Frederick, Md. A series devoted to the “Life of Lincoln” includes an illustration of a debate between Lincoln and Douglas, later used on a commemorative postage stamp in 1958.

Another fascinating subseries spotlights the illustrations of Andersonville Prison by Ezra Hoyt Ripple of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry. Ripple documented the conditions he suffered as a prisoner of war, and related his experiences to James E. Taylor, a prominent artist for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Ripple used Taylor’s vivid illustrations in Magic Lantern exhibitions, and included them in his memoirs, Dancing Along the Deadline.

The heyday of Civil War Magic Lantern shows occurred in the 1870s. The introduction of the motion picture around the turn of the century signaled its death knell. By 1910, the Magic Lantern had all but disappeared from the American landscape. Ironically, Beale, the medium’s best-loved artist, contributed to its demise. He pioneered and implemented innovative techniques adopted by the fledgling movie industry—developing creative camera movements, optimum lighting, storyboarding, and editing methods that endure to the present day.

In addition to its important, though little recognized role as the precursor of motion pictures, Magic Lanterns also inspired the 35mm slide projector. These machines became a staple in offices, classrooms and conferences until the advent of the Digital Age.

Today, Magic Lanterns live on in private and public collections. The Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History in Washington, D. C., houses an outstanding collection of Magic Lanterns and related objects. The Library of Congress also contains nearly 200 Civil War Magic Lantern glass slides.

Special thanks and much appreciation to Kenneth Leto for digitizing and organizing the images.

Robert Marcus collects Civil War Magic Lantern slides and related items. He has presented shows at Ford’s Theater and Lincoln’s home site on behalf of the National Parks Service. His current project involves a feature length documentary film and accompanying book to faithfully recreate an authentic Civil War Magic Lantern exhibition and lecture. His goal is to generate new interest in this long lost art form once at the forefront of American entertainment, enjoyment and education.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.