By Kurt Luther

In January 2020, John Banks posted on his Civil War blog a detailed examination of a glass negative in the Library of Congress (LOC) collection, titled, “Washington, D.C. Company I, 9th Veteran Reserve Corps, at Washington Circle.” The photo depicts a company of Union soldiers, dressed in sack coats and white gloves, standing at parade rest in front of the George Washington equestrian statue in Washington, D.C. A mustachioed lieutenant or captain leads the group. Banks noted that the photo might have been taken on April 9, 1865, the day of Lee’s surrender.

A few days later, the Center for Civil War Photography (CCWP) made a Facebook post about the same photo. It had noticed via John’s blog post that several soldiers in the photo, including the company commander, wore the number “10” on their caps, apparently contradicting the identification of the “9th [Regiment] Veteran Reserve Corps” in the LOC caption. The CCWP post also raised the possibility that some soldiers wore “H” company letters on their caps, rather than exclusively “I” as the caption would suggest. The post ended with a question: “Does anyone know why the Library of Congress identified this group as comprising part of the 9th VRC and only Company ‘I’?”

As a photo sleuth and a resident of the Washington area, I was doubly motivated to try to solve this mystery. Little did I know how far down the rabbit hole I would go before surfacing with new information and discoveries. The investigation in this column required integrating a wide range of tools and sources, including photos from multiple public archives, regimental histories, community expertise, and the Civil War Photo Sleuth website.

Correcting the captions

My first step required trying to locate other photos of VRC soldiers in Washington Circle in the LOC holdings. I thought if I could find more, I could compare them and see if perhaps one of the captions was accidentally swapped or duplicated. I knew from past experience that the LOC occasionally has two identical or similar views with different captions.

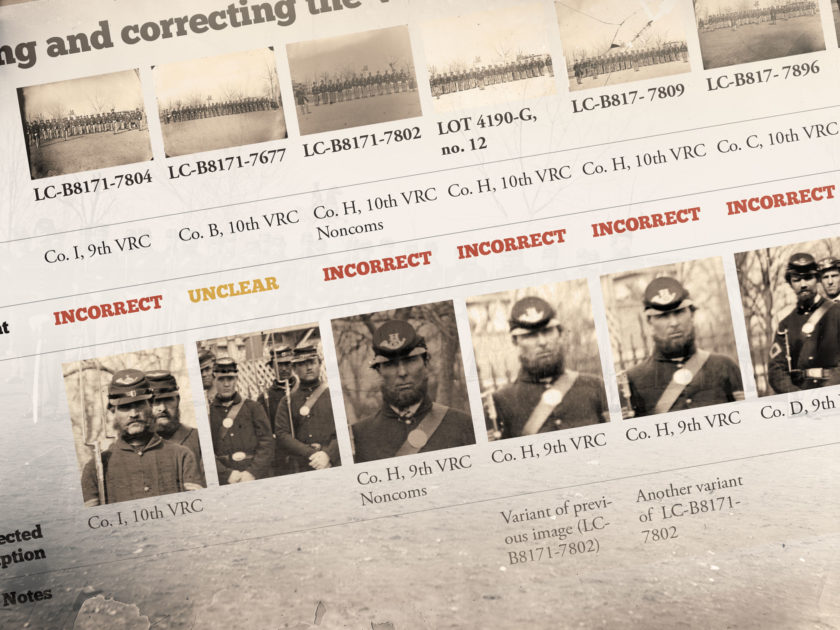

Searching the LOC collections online for various combinations of keywords like “veteran reserve corps” and “washington circle,” I located 13 unique views of soldier groups in Washington Circle. Most of the captions indicated the soldiers were members of either the 9th or 10th VRC regiments. However, a few captions lacked key information. For example, one caption mentioned “Co. F” without specifying the regiment, while another simply stated, “Veteran Reserve Corps.”

I began visually inspecting each photo in the group, starting with the original photo in question, labeled as Co. I, 9th VRC. I agreed with the CCWP that the number “10” and hunting horns on many soldiers’ caps clearly identified them as members of a 10th Infantry regiment. In contrast to CCWP, however, I thought all of the hat brass looked like “I” company letters, though blurring caused some to look like an “H.” Thus, I concluded this photo actually depicted Co. I, 10th VRC, rather than Co. I, 9th VRC.

I used a similar method to analyze the rest of the photos, focusing on the cap insignia. I soon discovered that many captions were incorrect. Moreover, there was no obvious pattern to the errors. Sometimes, as in the previous example, only the regiment number was off. Three other photos labeled Co. H, 10th VRC, two showing the whole company and another with just noncommissioned officers, actually depict Co. H of the 9th VRC.

In other cases, both the regiment and company descriptors were wrong. For example, two photos captioned Co. C, 10th VRC, one with soldiers at parade rest and another at order arms, actually show Co. D of the 9th VRC. A couple of photos, one labeled Co. B, 10th VRC, and the aforementioned “Co. F” photo, could not be conclusively identified because of the blurry insignia.

Two photos, Co. E, 9th VRC, and Co. K, 9th VRC, had clearly correct captions. Another photo, the vaguely-titled “Veteran Reserve Corps,” turned out to be a variant of the correctly labeled Co. E, 9th VRC photo. The remaining two photos, both labeled Co. A, 10th VRC, posed more of a challenge. Despite the identical captions, they clearly show two entirely different groups of soldiers, one group wearing the signature VRC shell jackets and the other clad in sack coats, led by different officers. A close look at the sack-coated soldiers’ cap insignia revealed them to instead be members of Co. A, 9th VRC.

The shell-jacketed men were a tougher nut to crack because, while their hat brass clearly indicated Co. A, the regiment numbers were blurred. While able to rule out the 9th VRC, they could be any other VRC regiment. Facing this obstacle, I performed some web searches to see if I could find other photos of the 10th VRC. I got lucky. In 2018, Steve Rogers had posted in the Civil War Faces Facebook group a carte de visite of a Union captain with a missing arm. The community helped Rogers decode the carte’s period inscription and identify the officer as Hamilton Lieber, who, after losing his left arm at Fort Donelson, transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps as captain of Co. A, 10th Regiment. Rogers spotted Lieber in the LOC photo, unmistakable with his bushy mustache and pinned left sleeve. Thus, his research allowed me to confirm this photo’s caption of Co. A, 10th VRC as correct.

Identifying the mystery officers

At this point, I had completed a first pass through the 13 photos, correcting seven erroneous captions, refining one vague one, and confirming three correct ones. However, I wasn’t yet finished. My earlier web searches for 10th VRC reference imagery had uncovered a couple more mislabeled photos in the LOC archives, these depicting VRC soldiers not in Washington Circle. The first, captioned “Officers of the 9th or 10th U.S. Veteran Reserve Corps,” was in fact a variant of another LOC photo correctly labeled “Band Quarters of the 9th or 10th Veteran Reserve Corp,” showing a group of VRC musicians gathered in front of a building. The group’s headwear, along with a painted sign on the building, indicates this is the 9th VRC band.

The second photo, captioned “Company D 10th U.S. Veteran Reserve Corps,” was much more interesting. I had excluded this photo from my original dozen because, unlike all of those photos, the subjects were not standing in formation at Washington Circle. Instead, this photo depicted a group of 17 sword-bearing officers seated on the porch of a building, a battle-torn national colors positioned between them. Additional soldiers and civilian men standing on the second-floor balcony complete the picture.

Examining the photo in detail, I quickly realized the officers were not members of the 10th VRC, or any other VRC regiment for that matter. Many wore the crossed cannons insignia of artillery, VI Corps badges, or both. Most had the subdued rank insignia typical of late-war officers, helping to date the image. Aside from these symbols, not one soldier displays regiment numerals or other distinctive clues to identify the unit, much less the soldiers’ names.

Faced with this brick wall, I turned to the Civil War Photo Sleuth website, which can be useful for generating new leads when all else fails. I focused on identifying several of the officers with distinctive facial features and visible rank and branch insignia, both of which helped narrow down possibilities. The first officer I searched, a captain with prominent ears, yielded no promising results. My second attempt, a youthful first lieutenant with carefully parted hair, also led nowhere. The third officer I tried, a handsome first lieutenant with light-colored eyes, returned a top match that caught my attention: Robert Finley, who served as first lieutenant of Co. M, 9th New York Heavy Artillery and, later, the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery. The reference photo came from a period-inscribed carte de visite in the New York State Military Museum’s Civil War collections.

Both photos showed strong facial similarity, including a close-cropped mustache and light-colored eyes. Both soldiers wore a VI Corps badge on their left breasts, rotated at the same 45-degree angle. Even when I removed the “artillery” and “first lieutenant” search filters and compared my unknown officer against all Union soldiers in the CWPS database—more than 21,000, as of this writing—Finley still emerged as the top facial match. I was excited, yet not enough evidence existed to make a firm conclusion.

If the unknown officer is indeed Robert Finley, then my working assumption was that the mystery photo depicts him with his fellow officers in either the 2nd or 9th New York Heavies. Some preliminary research on the regiments revealed that most of the 9th mustered out in June 1865. But two companies that had enlisted later than the others transferred to the 2nd for a few more months of service. These men formed a new “9th Battalion” within the 2nd, commanded by Maj. Sullivan B. Lamoreaux.

I remembered the 9th New York Heavy Artillery from an interaction a few years back with Kyle Stetz, who collects images from that regiment. Kyle had directed me to the 9th’s regimental history. Published in 1899, the book is also available in a searchable, digital form on archive.org. As I paged through the digital book, I was unprepared for what I was about to find. Printed on page 54 was an exact copy of the mystery photo I was trying to identify! Although the individual officers are not named, the caption reads, “Headquarters 9th Battalion, 2d N. Y. H.A, Fort C.F. Smith.”

Now that I had a definitive match for the regiment, I eagerly pored over the rest of the 600-page book, which contained an unusually large number of portraits. Unfortunately, they did not include Robert Finley. However, I found something even better: Identifications for the two other unknown officers I had previously searched on CWPS and come up empty-handed. On page 510, I discovered that the young lieutenant was named H. Hill Wheeler, Jr. On page 516, I found the prominent-eared captain, Lendall H. Bigelow. The same page contains a portrait of the battalion commander, Sullivan Lamoreaux, who strongly resembles the unknown field officer seated at the center of the mystery photo—a welcome bonus. None had reference photos in the CWPS database.

Closing the loop

Beyond the regimental history, the identification of the regiment enabled more discoveries in the LOC archives. I searched “2nd new york heavy artillery” and quickly realized this unit was one of the most photographed in all of Washington. One of the search results was a photo of the same headquarters building a few days later, inscribed Sept. 2, 1865. Capt. Bigelow and Lt. Wheeler reprise their roles, but this time, Bigelow traded his cap for a wide-brimmed hat and Wheeler wears his sash diagonally as the officer of the day. The pair feature prominently in several other views in the LOC collections of Fort C.F. Smith, albeit unidentified until now.

Another search result produced an orphaned albumen print of the mislabeled Co. D, 10th VRC photo, this one with a correct caption attributed to Bob Zeller, “Officers of 2d New York Heavy Artillery Fort C.F. Smith, near Washington D.C., August, 1865” (LOT 4187, no. 54). Satisfied with this confirmation, I could now contribute the identities of some of the pictured officers. I suspect that future photo sleuths can identify several more.

Returning to the question that started this project, “Does anyone know why the Library of Congress identified this group as comprising part of the 9th VRC and only Company ‘I’?” I do not know why this or any of the other seven photos was mislabeled; there was no clear pattern. But as we discussed in the Winter 2019 edition of this column, even authoritative sources such as public archives can contain errors. Many, including the Library of Congress, welcome the public’s help in catching them. Diligent photo sleuthing allows us to not only correct the historical record, but also often generate new insights along the way.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Lost and Found in the Library of Congress”

Comments are closed.