By Adam Ochs Fleischer

For as long as I’ve studied and collected Civil War images, I’ve noticed one question that seems to plague me and my colleagues above all others: “Do you recognize this backdrop?” It is the pestilence of our field, uttered with such alarming frequency I almost imagine it as semi-autonomous, a compulsive biological function that often follows an exciting new acquisition.

“Yes, I’m really pleased with the image, do you happen to recognize the backdrop?”

“Gesundheit.”

The answer is almost always no. And if it is recognized, it’s very likely one of few that are widely known (i.e. Benton Barracks of St. Louis). The best you usually can hope for after that is a vague suggestion of what region it was taken in or a lead to someone who might have the answer—generalities such as, “this looks very similar to others identified to soldiers in the Army of the Potomac,” “Ah, this must be in the western theatre because of the river and ironclad on the water,” or “My friend Arnold definitely would know but he lives in Myanmar now and can only be contacted by carrier pigeon. Good luck.”

This column will methodically examine one or several backdrops, not just with the aim of determining who took the photograph and where they were located, but also to evaluate the artistry of the backdrops themselves. For instance, if an example incorporates elements distinct to a certain area. To anyone who has examined painted backdrops, it becomes immediately clear that there do seem to be regional differences and influences. Many were exceedingly similar to one another sans a few subtle differences. Also, it seems quite common for a backdrop’s scenery to reflect the real area of the studio’s location.

Because of the volume of backdrops that were used and their similarity, this column will largely focus upon examples that incorporated a military aspect to their design, or, a distinctiveness that merits study and dissection.

What I find especially compelling about this subject is the little scholarship it has received. While particular backdrops have been excellently researched, the broad examination of backdrops during the Civil War has largely gone ignored. And the field is ripe for harvest. We know very little about who produced them for instance, where they were offered or how much they cost, and we have yet to find a surviving example from the period. Hopefully this effort will put us a step forward in better identifying different backdrops and understanding their use.

What I find especially compelling about this subject is the little scholarship it has received. While particular backdrops have been excellently researched, the broad examination of backdrops during the Civil War has largely gone ignored. And the field is ripe for harvest. We know very little about who produced them for instance, where they were offered or how much they cost, and we have yet to find a surviving example from the period. Hopefully this effort will put us a step forward in better identifying different backdrops and understanding their use.

For this inaugural article, I’ve chosen to write about the backdrop used by photographer “J. Jones” who worked at the “Rendezvous of Distribution” near Washington, D.C. I’ve long been interested in Jones’ images, but his origins and work really began to percolate in my mind after a carte de visite depicting him was sold at auction recently.

Rendezvous of Distribution

The “Rendezvous of Distribution” was organized during January 1864 in Arlington County, Va. It consolidated a camp for convalescents and a distribution center that processed soldiers awaiting orders or newly paroled from prison. Its first iteration was known as “Convalescent Camp,” and was established in September 1862 following the Second Battle of Manassas. Word quickly spread of its poor conditions. Clara Barton remarked in October 1862 that it was “sort of pen into which all who could limp, all deserters and stragglers, were driven promiscuously.” The state of affairs was evidently so horrid that the camp was for a time better known as “Camp Misery.” A more detailed description can be found in the letters of Pvt. George Cheney of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry, stationed in the camp, who wrote in November 1862, “I wish you could only step into this camp one moment and see for yourself the beauties which dwell within. Mud slippery as glass, tents filthy in the entrance. Many of the men without blankets sleeping on the cold wet ground. Others—many of whom arrive in the afternoon from other hospitals, are obliged to sleep in the open air. This the accommodation for convalescents, men just recovering from wounds or sickness of a variety of kinds, whose systems reduced by disease are fully alive to the deadly malaria which is known to exist in the vicinity of rivers and swamps. The wonder to those who have visited this place is, that men manage to live at all.”

The situation began to improve soon after, ostensibly the result of numerous complaints to the War Department and to elected officials. After several visits at the behest of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and the federal government, supplies were sent and Lt. Col. Samuel McKelvy was appointed to take charge of the camp. McKelvy, a native of Pennsylvania who founded a successful cast-iron business before the onset of hostilities, had a seeming knack for organization and had received ever-increasing charges of responsibility throughout the war relating to commissary and provisions. Tasked with overhauling the camp and improving its conditions, McKelvy did not waste any time. A colored lithograph from 1864 depicts the camp (after McKelvy’s appointment) as quite the operation, with hundreds of tidy-looking barracks and tents arranged in military rows, large headquarters for officers and staff, a receiving office, post office, library—and a “photograph establishment.” Soldiers can be seen marching through the camp itself, illustrating a now fully-functioning facility. It seems likely that this lithograph was intentionally produced to show how vastly the camp had improved under McKelvy’s leadership and to dispel lingering rumors of its prior mismanagement.

The re-organization of “Camp Convalescent” came in January 1864 by order of the War Department. Special Orders No. 20 specified that the newly named “Rendezvous of Distribution” was to henceforth serve as the place “from which all men fit for field service arriving in the Department of Washington” would be distributed to their regiments, and that “only men fit for service and deserters would be sent to this rendezvous.” Those who were not fit for active duty were to be sent to the Invalid Corps (Veteran Reserve Corps) or dismissed from service. The new camp had three divisions: One still intended for convalescents (who would soon be fit for service), a second for distribution, and a third for processing paroled prisoners. The news of this re-organization was met cheerfully, with a periodical published in the camp called Soldiers’ Journal stating in its first issue that “we are happy to state, however, that although the name and the manner of its workings has changed, the same good genius that organized and brought old Convalescent Camp from the despicable condition to which irregular government had consigned it, to a high state of discipline and responsibility, is still to preside over the new camp in the person of Samuel McKelvy, Lt. Col. Commanding.”

In a later issue of the Journal, an account of the camp’s history happens to mention a photographer—“the photograph gallery of camp under charge of Mr. Jones, an old and experienced hand at the business, is visited daily by the soldiers, having their bronzed faces taken to send to families and friends. The pictures taken in that establishment can compete with any in our principal cities, and the charges are moderate. Mr. Jones always obliging to the soldier, allows no room for complaint on the part of his work. He is a regular “E pluribus Erin ga brath.”

John Jones, photographer

Mr. Jones, or J. Jones as his imprint reads on surviving images, is an elusive character. As one might imagine, a great thundering herd of J. Jones’ existed during the war. Finding the right one has proved difficult. What we know from the Soldiers’ Journal description is that Jones had experience. One plausible candidate on this account is a John Jones, a daguerreotypist operating in Baltimore circa 1850-1855. Without more circumstantial evidence, however, the possibility proves at best speculative. Another interesting hint from the Journal account states in closing that Jones is a “regular “E pluribus Erin ga brath,” suggesting an Irish background. A review of 1860 and 1870 census records unfortunately does not help when only Jones’ born in Ireland are considered.

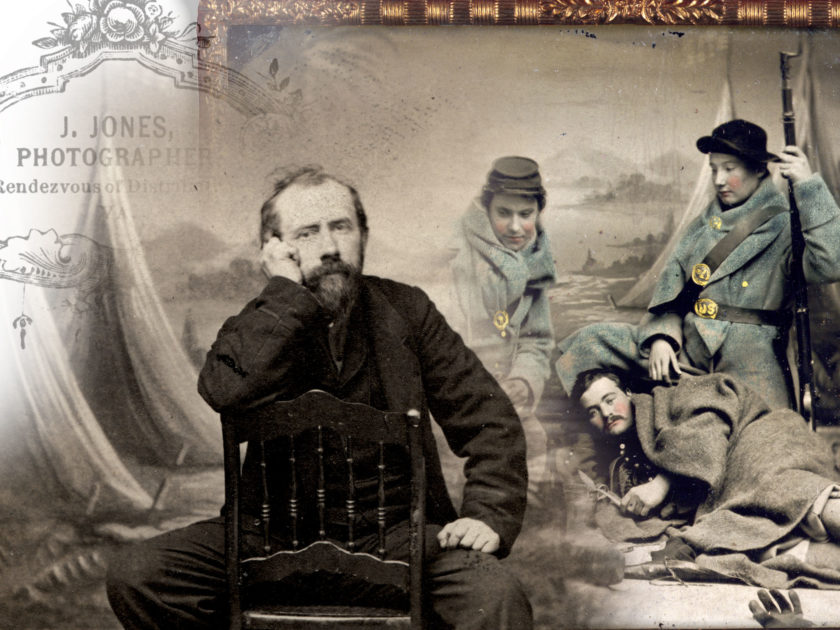

Recently surfaced photos have perhaps solved the mystery. In November 2019, a carte de visite inscribed “John Jones” depicting a man in civilian clothing with the “J. Jones, Rendezvous of Distribution” back mark was sold at Heritage Auctions in Texas. The auction house described the person pictured as J. Jones the photographer himself, a fair and likely assumption. Sold with the carte was an image of a bespectacled man identified as “Henry H. Clark,” and bearing the same back mark. A “Henry H. Clark” worked as a daguerreotypist in Baltimore at the same time as the previously mentioned “John Jones” of Baltimore. Clark is probably best known for his full plate panoramic photos taken of Baltimore now held by the Peale Museum. The circumstantial evidence of the two photos being found together bolsters strongly the suggestion that the two men were, in fact, contemporaries.

The man identified as Jones is middle-aged and almost bald (lending additional credence to the possibility that the appropriately-aged Baltimore daguerreotypist is our man). He sits in a backwards-facing chair, tilted slightly forward, with his head gently leaning on one hand. He stares directly into the camera with almost a wistful look. It’s a tender and casual portrait.

A careful appraisal of Jones’ work publicly sold or published has led to several notable observations. First, there are two variations of his cartes de visite back-mark, one which reads “J. Jones, Photographer, Rendezvous of Distribution, Va.” and another that reads “J. Jones, Augur Gen’l Hospital, Late Ren. Distribution, Va.” The camp hospital became known in early 1864 as “Augur General Hospital” and gained in prominence as the war drew to an end. The Soldiers’ Journal began describing itself as being published in “Augur General Hospital” and not the “Rendezvous of Distribution” sometime in early to mid 1865.

Based upon this chronology, we can comfortably assume that images back marked “Rendezvous of distribution” date from January 1864, when the “Camp Convalescent” title ended. From early-mid 1865 and henceforth, the “Augur Gen’l Hospital” back mark was used until the hospital became defunct in August of the same year. Even though Jones’ back mark changed, there are numerous examples of the same painted patriotic backdrop used with both variants. Tintypes (and every known example is a tintype) that utilize Jones’ backdrop can be reasonably assumed to have been created during the same window of time that Jones’ cartes de visite, between January 1864 and August 1865.

Based upon this chronology, we can comfortably assume that images back marked “Rendezvous of distribution” date from January 1864, when the “Camp Convalescent” title ended. From early-mid 1865 and henceforth, the “Augur Gen’l Hospital” back mark was used until the hospital became defunct in August of the same year. Even though Jones’ back mark changed, there are numerous examples of the same painted patriotic backdrop used with both variants. Tintypes (and every known example is a tintype) that utilize Jones’ backdrop can be reasonably assumed to have been created during the same window of time that Jones’ cartes de visite, between January 1864 and August 1865.

Some of Jones’ images reveal a creative flair not often evident in period photos. He produced several known double exposure, or “trick” photographs, with perhaps the most famous being an image of a seemingly headless soldier holding a severed head in each of his hands (pictured on the cover of a 2004 issue of MI). Jones utilized props such as whiskey bottles and cigars; posed soldiers in interesting ways; and frequently changed camera angles.

A handful of known horizontal Jones’ cartes de visite include one of Lt. Col. McKelvy, and imply an eye for composition. Jones’ own careful and candid self-portrait also reveals an expressive style typically not seen in images taken during the war. Overall, the breadth of his extant work suggests a competent, sometimes playful photographer with an artistic flair.

The Backdrop

Jones’ backdrop was painted with great skill to give the impression of a landscape receding backward into the distance from the picture plane. The effect is a successful illusion. On the viewer’s left in the foreground (if examining a carte) is a pair of Sibley tents, one seemingly more distant and crowned by an American flag. In the center of the backdrop is a winding river, perhaps the Potomac, that disappears into a mountainous expanse. Embanked on the river’s right is a row of Sibley tents, a few more situated in the distance, with a tall tree standing in their midst. Following the right side back towards the picture plane is a palm tree, and in the immediate foreground a tropical-looking plant.

Call to Action

Are you aware of information regarding a backdrop’s location and/or photographer that’s never been published? Is there a particular backdrop that’s stumped you for years? Do you have an idea for the next subject to explore? If so, I am happy to receive comments and suggestions. While this column will initially categorize different observations and connect newly learned material, a much more broad focus will be its ultimate goal. I hope to eventually study regional trends and aesthetic differences in the work of the artists who produced backdrops. An investigation of these more general topics depends upon a vast assemblage of information, and I am indebted to the many kind collectors and readers who have already contributed to this effort. Please reach out with what you know or hope to know!

Special thanks to Ross J. Kelbaugh for sharing his knowledge and images.

Adam Ochs Fleischer is passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Chicago, Ill.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

2 thoughts on “A Daguerreian Pioneer at the Rendezvous of Distribution”

Comments are closed.