Featuring images from the images from the Jerry Everts Collection

On Sept. 12, 1864, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman responded to a request from the mayor of Atlanta to reconsider orders to evacuate non-combatants from the beleaguered city. Sherman’s answer includes a passage that sums up his views on war.

“My orders are not designed to meet the humanities of the case, but to prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside of Atlanta have a deep interest. We must have peace, not only at Atlanta but in all America.”

This communication and others exchanged between Sherman, Atlanta’s civilian leaders and Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood on the subject of evacuation resonate 150 years after they were written. For Jerry Everts, a collector of Sherman portraits, the story that these letters tell is his favorite account of the famed Union commander. “I always looked at this situation as the beginning of the personality of “Burning Billy Sherman,” Everts observes.

Everts first became aware of Sherman thanks to a high school American History class. His interest further peaked after a relative told him about an ancestor who marched with Sherman. The ancestor, George Struble, a corporal in the 38th Ohio Infantry, died in the Battle of Jonesboro, Ga., on Sept. 1, 1864, just days before the memorable communications about the evacuation of Atlanta.

“I love to look at an image and study the character of the person pictured. It tells a great story about these soldiers.”

A native of Adrian, Mich., Everts attended his first Civil War collector’s show in the 1980s “It was run by Dave Parks in Southfield, and it was where I was first introduced to cartes de visite. I ended up buying a large number of images from a dealer and have been hooked ever since. I bought my first image of Sherman in 1984. It was a seated image of Sherman that I still have today.”

“I think that I have developed a passion for images because this was the first conflict where we could see the faces of the men who fought it,” Everts notes. “I love to look at an image and study the character of the person pictured. It tells a great story about these soldiers.”

One of those characters is Sherman. Born in 1820, his narrative follows a memorable arc. West Pointer—Unremarkable post-graduation military career—Questions about his mental stability early in the Civil War—Enduring friendship with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant—Father of modern warfare—A gift for piercing quotes—General of the Army.

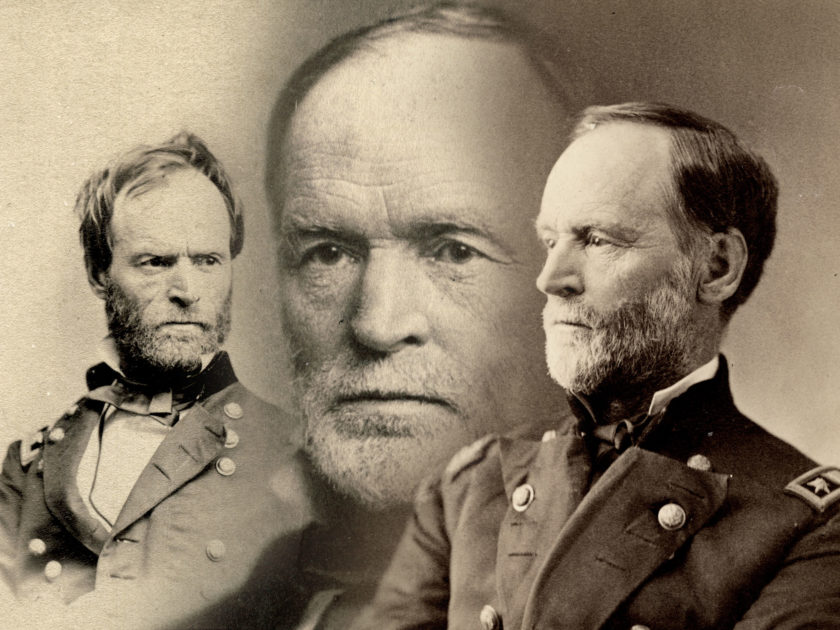

Sherman’s complex nature emerges through these portraits. They span Sherman’s life from the beginning of the Civil War to his retirement years.

“I think it is important to remember Sherman for the remarkable place he holds in history,” Everts observes. “He was a beloved hero to a great many Americans, especially ‘his boys.’”

1862-1863

Two Stars after Shiloh

May 1862: This is possibly the first image of Sherman as a major general. His left arm appears limp, which may indicate the effects of wounds he sustained to the hand and shoulder during the Battle of Shiloh.

Portraits for Ellen?

September 1862: This pair of portraits is believed the same referred to by Sherman in a letter home to his wife, Ellen, on Sept. 25, 1862. “I send you two more daguerreotypes or cards—Sister Ann asked me for one. I have just sent her two—John two, and you two—so I think my picture will have more circulation than is prudent.”

September 1862: This pair of portraits is believed the same referred to by Sherman in a letter home to his wife, Ellen, on Sept. 25, 1862. “I send you two more daguerreotypes or cards—Sister Ann asked me for one. I have just sent her two—John two, and you two—so I think my picture will have more circulation than is prudent.”

Raised Brow

1863: Sherman’s raised brow suggests an inquisitive frame of mind. This portrait is believed previously unpublished.

Unique Badge

1863: Sherman wears the Department of Mississippi badge in this post-war stereoview card of an earlier portrait. Everts notes: “This badge is totally unique to William Tecumseh Sherman. The only other people that I have seen wear it were a couple of his staff officers.” He adds, “I believe Sherman may have had these done in a very limited amount, maybe six or eight. The acorn represents the 14th Army Corps, The cartridge box on the shield represents the 15th Army Corps, the arrow represents the 17th Army Corps, and the shield represents the 23rd Army Corps. These corps were only together until October 1864.”

1864

1,000-Yard Stare

1864: An unusual and perhaps unpublished view of the general. “He is looking straight into the camera and saying beat me if you can,” Everts notes.

A Carte in a Carte

June 1864: As Sherman’s reputation as a military leader grew, so did requests for his likeness. The photographer who pirated this May 1862 portrait did not bother to crop the mount out of the copy print, making it a carte de visite in a carte de visite.

Bad Hair Day

1864: Much has been made of Sherman’s unruly hair in this portrait—one of at least three views made in a single sitting. No primary source documents shed light on the cause of the mussed style. It is fair to state that he was not alone in being captured on a bad hair day.

American Napoleon

1864: Sherman thrusts his hand into his coat a la Napoleon—an often-repeated pose by many officers. In this case, the reference to the French military icon recalls a speech by Confederate President Jefferson Davis after the fall of Atlanta, and before the March to the Sea. “Our cause is not lost. Sherman cannot keep up his long line of communication, and retreat sooner or later he must. And when that day comes, the fate that befell the army of the French Empire in its retreat from Moscow will be re-enacted. Our cavalry and our people will harass and destroy his army as did the Cossacks that of Napoleon, and the yankee General like him will escape only with a body guard.”

Classic Sherman

1864: “This is classic Sherman with his very gruff look and mussed hair. I love the scowl on his face and the bravado,” Everts observes. The tax stamp on the back of the mount, proceeds from which paid for the expensive war, is dated Sept. 12, 1864—two weeks after Atlanta fell to Sherman’s army.

1865

Studious General

July 1, 1865: The general strikes a studious pose, seated with pencil and paper at a table stacked with books, and his hat at his feet. The date and Chicago back mark suggest Sherman sat for this portrait during his two-week visit to the city in mid-June 1865. Everts recently added this to his collection. He observes, “In all the years I have been collecting Sherman, I have never run across this photo.”

Surrender

1865: The Sherman-Johnston surrender scene pictured here was copied without credit from a lithograph published by Currier & Ives in 1865.

In Victory

April 1865: Sherman exudes confidence, wearing his Department of the Mississippi badge. Though it was obsolete by this time—the 23rd Corps had been pulled out and ordered to Nashville in November 1864—Sherman continued to wear it through the rest of the war, and beyond.

Team Sherman

April-May 1865: One of the best-known portraits of Sherman pictures the victorious commander with his generals: John A. Logan, Henry W. Slocum, Oliver O. Howard, William B. Hazen, Jefferson C. Davis, Joseph A. Mower, and Francis P. Blair, Jr. The image is also notable for the addition of Blair, right, who was not present during the original sitting. His likeness was added in the darkroom—1860s Photoshop.

In mourning

1871-1872: Sherman is the quintessential warrior as General of the Army. Note the four stars on his shoulder straps. This insignia was worn first by Grant, then Sherman, between 1866 and 1872. These portraits are credited to Hoyt of The Brady National Gallery, located at 627 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. Gabriel P.B. Hoyt is listed as a photographer at that address in an 1877 city business directory. Hoyt may have printed these images from original Brady negatives.

Wartime loyalty

1872-1873: Though the war ended five years earlier, Sherman continued to wear his Department of the Mississippi badge. Note the clipped signature.

Shoulder Straps

1875-1876: Sherman wears shoulder straps that feature the U.S. coat of arms flanked by stars, a design he implemented in 1872. Sherman’s successor, Philip Sheridan, wore the same insignia.

Final years

In Retirement

Early 1880s: Now a graying civilian, Sherman’s creased brow, taut face, and determined expression were easily recognizable to the soldiers who stood with him at Vicksburg, Atlanta, and elsewhere during the late war.

Wearing the Uniform

1888: Though Sherman retired from the army in 1884, he dressed in full uniform once again for New York celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony. Engravings of this view appeared in the second edition of Sherman’s Memoirs and on a postage stamp.

Time Capsule

Late 1880s: Prominent Chicago photographer Charles D. Mosher took this photograph as part of an exhibit planned for the nation’s 1976 bicentennial. Sherman’s likeness and those of other prominent men and women were part of a time capsule.

“They are to be classified and deeded, with memoirs and valuable statistics, to Chicago, and preserved with the city archives in a memorial safe in the great vaults of the Court House, where suitable space has been provided by the Council,” read an official statement. “There will be a request in the deed to have the Mayor of Chicago, in 1976, confer with the Centennial Commission to provide a place for these portraits and statistics in Memorial Hall, at the Second Centennial Anniversary of American Independence.”

The memorial vault holding the images was destroyed when the court house was razed in 1908. The photographs, however, were saved. On June 12, 1976, an exhibit featuring the images and other relics opened at the Chicago Historical Society. The mayor of Chicago at this time was Richard J. Daley.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.