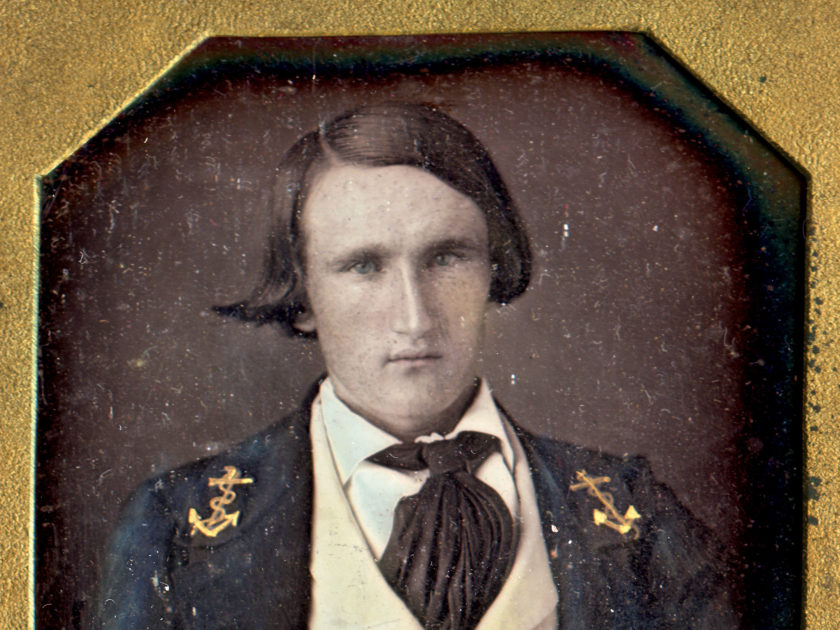

A Rear Admiral’s Son

John Wilkes, Jr., sat for this portrait about 1847, the same year he graduated from the Naval Academy. Known as “Jack” to his friends, young Wilkes followed in the footsteps of his father, Charles Wilkes, a career naval officer who attained the rank of rear admiral. The elder Wilkes is best known in antebellum times for his exploration of Antarctica and during the Civil War for the Trent Affair in which he stirred international tensions after his removal of Confederate diplomats from a British mail steamer.Unlike his father, Jack did not make the navy his career. He resigned his commission in 1854, married, and settled in Charlotte, N.C., where he started a family that grew to include five children that lived to maturity.

During the years leading up to the secession of North Carolina, he became the owner of a flour mill and an iron works. After hostilities broke out between North and South in 1861, he served in the Home Guards, advised state officials on financial matters, and became involved in railroad construction. Likely during this time, he became known as “Captain” Wilkes.

Wilkes continued as a prominent member of Charlotte’s civic and business community after the war ended. Though his navy days were long over, his relatively brief stint in the service stamped his character. Upon his death in 1908 at age 81, his newspaper obituary noted that, “He always retained much of the bluff mannerisms of the sailor, but his brusqueness covered as kindly a heart as ever beat in a human breast.”

Up From the Bottom of the Sea

In 1853, about three years after he sat for this portrait, Midshipman and math whiz John Gardner Mitchell became a footnote in history. On July 7, aboard the brig Dolphin in the North Atlantic, he made a deep-sea sounding. This in itself had already been done. But what put Mitchell in the history books was described by Lt. Matthew Fontaine Maury, the distinguished oceanographer and career navy officer: “To him belongs the honor of bringing up the first specimen that was ever obtained from the bottom of the deep sea.”

Mitchell accomplished this feat using Brooke’s Deep Sea Sounding Apparatus, an ingenious device that used a hollow rod slid through a cannonball that acted as the plummet.

And what of the first specimen? Mitchell described what he found inside the rod as “a fine, chalky clay.”

This event marked the highlight of Mitchell’s early years in the navy. After graduating second in the Academy’s Class of 1856, he went on to distinguished Civil War service that culminated with the Mississippi River Squadron as commander of the ironclad Carondelet.

Poor health forced him to take a leave of absence in late 1864. He returned to active duty in 1865 with the Pacific Squadron. The Massachusetts native came to call California home. On Oct. 21, 1868, while recruiting seamen in San Francisco to replenish the crew of his sloop-of-war Saginaw, he encountered two men and may have tried to recruit them. The situation turned ugly and ended when one of them struck Mitchell a deadly blow. The motive for his death remains a mystery. He was about 45.

Mitchell’s remains were buried on Mare Island, where the Saginaw was constructed. In 1869, Alaska’s Mitchell Bay was named in his honor.

Early View by Plumbe

Possibly one of the earliest images of a midshipman, this sixth-plate daguerreotype was taken by photography pioneer John Plumbe, Jr. Daguerreotype authority Cliff Krainik believes this portrait was taken no later than 1844. The Naval Academy did not open its doors in Annapolis, Md., until 1845, which suggests that this young man attended the Philadelphia Naval Asylum School, or one of the smaller academies in New York City, Boston, Mass., or Norfolk, Va.

Cap of Clues

The cap worn by this midshipman is key to placing him in historical perspective. The lack of a gold lace band and the presence of a fouled anchor is consistent with 1847 regulations. In 1852, the cap design changed when a wreath surrounded the anchor. The following year, the gold band was added after being absent for some time. One can fairly conclude he posed for this portrait between 1847 and 1852.

1841 Regs

These midshipmen are dressed in the coat that conforms to 1841 regulations, including the buttons and anchor insignia on the collar. Two men, bottom, hold caps with gold lace band. The other, right, possesses a Pattern 1841 cocked hat and a non-regulation, eagle-headed sword that dates to the mid-1840s.

These midshipmen are dressed in the coat that conforms to 1841 regulations, including the buttons and anchor insignia on the collar. Two men, bottom, hold caps with gold lace band. The other, right, possesses a Pattern 1841 cocked hat and a non-regulation, eagle-headed sword that dates to the mid-1840s.

Stars of Success

The stars above the fouled anchors on the collars of these navy officers indicate they are passed midshipmen. One man wears a white vest and trousers, indicating he sat for this portrait during the summer months. The other man wears five small buttons and an offset larger button on his cuff rather than the standard three larger buttons often found in portraits from this period. This arrangement is believed undocumented. “Maybe this was something worn at the Naval Academy for which nothing is recorded,” suggests MI Senior Editor Ron Field.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.