By Ross J. Kelbaugh and Ronald S. Coddington

Don’t go.

These simple words capture the essence of a father’s desire to protect a favorite son determined to serve in the Confederate army.

The father, Noah Walker, ranked among the elite of Baltimore’s merchant class. A self-made man, his story is rooted in Scottish ancestry and American capitalism. With a pragmatic head for business, he had worked his way up in the world.

Apprentice to a shoemaker. Grocery store clerk. Head of a successful clothier establishment with stores in other Southern cities. Scion of one of Baltimore’s wealthiest families. Lord of the Dumbarton mansion and 600 acres of land. Slaveowner. Widowed father of two sons.

He enjoyed a close-knit bond with his second son and namesake, Noah Dixon Walker. On the surface, the two seemed nothing alike. One historian described the young Walker as “evidently something of a dilettante” who spent his time traveling abroad.

Father and son shared a common sympathy for the Southern cause. The results of the U.S. presidential election of 1860 spurred the idealistic dilettante to action. A letter to his beloved father captured the outrage and indignation felt by many: “I believed that Abraham Lincoln had been placed in power by an insane political faction, upon the ruins of our once sacred Constitution, and that he and his party, to possess and hold the political power of the Country, would perpetrate any act however outrageous, to continue their unconstitutional authority.”

Young Walker happened to be in Europe when Lincoln won the election. He cut his travels short and crossed the Atlantic for home. He spent a few days with his father and family at Dumbarton, and then followed the path of many pro-South Baltimore men of military age from the Old Line State into the Old Dominion.

He arrived in Richmond, where the capital’s populace buzzed with excitement and energy. Writing with religious fervor, he determined to “espouse the holy cause of Southern freedom, and to enlist and battle under the sacred banner of independence.”

Old Walker objected. He made his son a lucrative offer: Forget about the Confederate army and go to England to aid the South from London. To sweeten the deal, he added the promise of a credit line of $200,000 —about $6 million in today’s dollars—to use it as he pleased.

The proposal had its merits. The plan would place his son in position to influence the future of the Southern nation through business savvy and greenbacks instead of sabers and guns.

Young Walker refused. His father may have expected this outcome and did not fight the decision. Instead, Old Walker provided uniforms to a company his son helped organize, the Richmond Zouaves. Young Walker, according to his family, faced a conundrum when the time came to elect officers. “Having formed the company, strong pressure was brought to get him to accept the captaincy of the same, but whilst preferring to enter the ranks as a humble private, he was finally induced to accept a lieutenancy.”

With Stonewall Jackson’s army

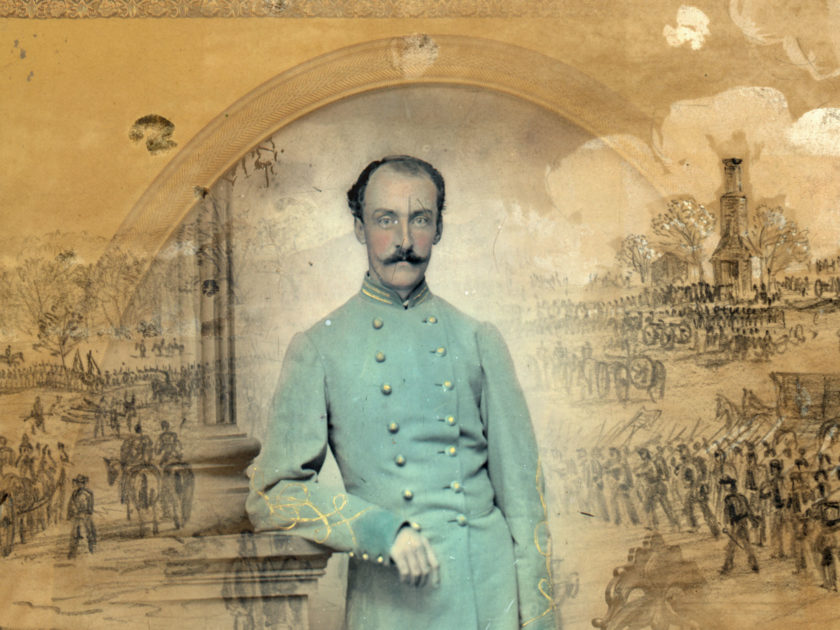

On June 10, 1861, 2nd Lt. Walker enlisted. He and his comrades became Company E of the 44th Virginia Infantry.

Three weeks later, the regiment left the confines of Richmond for western Virginia. The 44th arrived in time to participate in the Battle of Rich Mountain, and went on to engage in numerous skirmishes through the summer and autumn. The men suffered from bitter cold after severe winter weather blanketed the bleak mountainous region.

The spring of 1862 brought warmer temperatures and the heat of active campaigning. On May 8, the 44th arrived on the outskirts of McDowell with the rest of the Army of the Northwest, a relatively small force composed of two brigades. Here, it merged with a larger Confederate army led by Stonewall Jackson, and defeated Union troops commanded by generals Robert H. Milroy and Robert C. Schenck.

The Battle of McDowell occupies a place in history for its part in the early phases of Jackson’s masterful Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

When the brigade halted in the field and sat down he alone stood erect, went in front, and attempted to get the brigade to advance still nearer the enemy.

McDowell also proved the mettle of the 44th. The regiment formed in the center of its brigade in a slightly depressed section of an open field. As enemy artillery and infantry fire intensified, Col. William C. Scott, who commanded the 44th and the rest of the brigade, feared the low ground occupied by his Virginians was an advantage to the federals. So, he prudently ordered them into a reserve position behind infantrymen in the 58th Virginia.

Scott noted what happened next in his official report. “After the battle became very animated, and my attention was otherwise directed, a large number of the Forty-fourth quit their position, and rushing forward joined the Fifty-eighth and engaged in the fight, while the balance of the regiment joined some other brigade.”

So much for occupying a reserve position.

Walker, now first lieutenant of Company E, wrote to his father about the victory at McDowell, and noted, “This was my first connection with the Army of Stonewall Jackson.”

In fact, McDowell marked the beginning of a memorable association between the 44th and Jackson’s army. The regiment distinguished itself in the string of victories in the Shenandoah Valley during the spring, including Front Royal, Winchester, Cross Keys and Port Republic.

Walker recalled the latter fights with pride.

At Cross Keys on June 8, he wrote his father about a successful charge that routed the 39th New York Infantry, popularly known as the Garibaldi Guard for its heterogeneous ranks of European continentals. Col. Scott noted in his after-action report, “The Forty-fourth, numbering not more than 130 men, was attacked by two regiments of the enemy, and after exchanging a few rounds the Forty-fourth charged them gallantly with the bayonet and broke them, chasing them a considerable distance, killing several and taking some prisoners.” Union versions of the action on this part of the battlefield paint an unsurprisingly more positive picture.

At Port Republic the following day, Walker’s battlefield bravado earned a direct mention in Col. Scott’s official report, which was repeated by Scott’s superior officer and division commander, Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. “I particularly commend the gallantry of Lieutenant Walker, Company E, Forty-fourth Virginia. There may have been others equally worthy of commendation, but I could not fail to notice him. When the brigade halted in the field and sat down he alone stood erect, went in front, and attempted to get the brigade to advance still nearer the enemy.”

The vision of Walker standing tall in a farmer’s field at Port Republic illustrates the boldness of a courageous and determined officer. It is also fairly stated that Walker’s act captures the esprit de corps that drove Jackson and his army with seemingly unstoppable momentum and belief in the supreme victory of Confederate arms.

On to Richmond—and beyond

Port Republic ended the Valley Campaign. Jackson’s army marched to the outskirts of Richmond and teamed up with Gen. Robert E. Lee’s forces to bring the Union Army of the Potomac’s Peninsula Campaign to an end.

Walker’s Company E did not participate. Used up in the Valley, its remnants were ordered to Richmond on recruiting duty. Some two months later, the company reported to Battery No. 8 in the capital defenses near the Chickahominy River. Walker and his men spent the fall and winter months here while two momentous battles, Antietam and Fredericksburg, closed the 1862 campaign in the war’s Eastern Theater.

In early February 1863, Walker reflected on his war experience in a letter to Old Noah. “Thanks to Almighty God, I have passed through seven pitched battles uninjured and it is my ardent hope that his omnipotent arm will continue to protect me until I am restored to you and family and my friends. In all these scenes of danger, trials and hard ships through which I have passed, since I have parted with you my beloved father, a recollection of you has been my constant stimulus to exertion, a recollection of the pride and joy you would feel in any success of mine has been my perpetual inducement to increased and greater efforts.”

Walker and Company E returned to active duty in time for the Battle of Chancellorsville. They arrived in the rear of the Union army during the late afternoon of May 2, 1863, and by nightfall had driven the enemy from their entrenchments and into the darkness. They captured two cannon and numerous prisoners. The fighting closed with the regiment in line of battle to renew the combat. Losses had been relatively light.

Early the next morning, the 44th changed position, and at 6 a.m. moved forward with its brigade to the same trenches that they had taken the previous evening. There was little time to waste. Orders to advance were issued. Walker and his fellow officers organized the ranks and before long everyone went into motion. They marched as quickly as they could towards a mass of blue infantry behind breastworks. Within 70 or 80 yards from the enemy, Walker and his comrades received orders to halt, perhaps to dress lines and make final preparations to assault the Union line. The federals let loose with a barrage of artillery and musketry fire that hit the exposed brigade hard. Undeterred, the Confederates fired back.

As the regiment began to waiver before the onslaught of the foe, he waved the flag aloft with his left hand, and with his right hand brandished his sword, shouting ‘Forward, men, forward! For God’s sake, don’t give back.’

In the midst of the leaden hail, Walker made his way to the front of the regiment—much like he did at Port Republic. According to one account, the colors of the 44th had been shot down no less than six times before Walker seized them. “As the regiment began to waiver before the onslaught of the foe, he waved the flag aloft with his left hand, and with his right hand brandished his sword, shouting ‘Forward, men, forward! For God’s sake, don’t give back.’”

Another version of the story states that two color bearers had been shot down before Walker grabbed the flag and cried, “Come on my brave boys.”

Walker rallied the men, two hands held aloft, for just a moment. “The next instant he was seen to reel, his sword fell from his grasp; the colors drooped, and the splintered staff penetrated his hand and he fell to the ground, his regimental flag swathed around him from cap to sword belt,” according to the first account.

His captain, Edward M. “Ned” Alfriend, rushed to Walker’s side. Alfriend gently raised the wounded man, who rested his head against the captain’s knee. Walker, in a feeble voice, asked “Ned, where am I wounded?” Alfriend replied, “I don’t know, Noah.”

As Alfriend spoke these words, Walker fell back, dead.

Walker was two weeks shy of his 29th birthday. He never knew his comrades ultimately rallied and took the stronghold by storm. They held the position briefly, for a flank attack drove them back for good. But, for a few fleeting moments, the tattered flag shot from his hand waved triumphantly above the fray.

Epilogue

Walker never knew that the same battle was also the last fight for one of its chief architects, Stonewall Jackson. Nor did Walker ever know of the participation of the 44th in the near success at Gettysburg, or the grinding war of attrition along the lines of Petersburg. He never knew that a lone officer and 12 enlisted men of his regiment surrendered at Appomattox.

The exact nature of Walker’s mortal wounds went unrecorded. One version of his final act at Chancellorsville notes he “fell pierced in several places” in the third and successful charge.

Walker’s remains were reportedly buried on the battlefield under the shelter of a tree near the spot where he fell. They were housed in an improvised coffin, which may have been a blanket or a crude wood box. A day or two later, the body was disinterred and transported to Richmond. One report states it was hermetically sealed in a metallic casket prior to the trip to the capital. Another source notes it was embalmed in Richmond. Both sources agree that the remains were laid to rest in the city’s Hollywood Cemetery.

In the spring of 1866, survivors of Company E gathered inside the cemetery for a solemn ceremony to honor their late lieutenant. They did so with little fanfare, as the city remained under Union occupation. They placed a small silk Confederate flag with 13 paper stars pasted to its blue field on Walker’s grave. Fearing federal troops might destroy the little flag, they sent it to Old Noah with a letter of explanation.

About two years later, Walker’s remains were removed once more to a final resting place in the family plot in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery.

Old Noah mourned the loss of his much beloved son. More than a year later, in November 1864, military officials charged him with aiding rebel forces after a package containing a sword destined for Confederate cavalry Maj. Harry Gilmore of Baltimore turned up in his store. The charge was dismissed on his parole of honor. Baltimore socialite Sarah Hutchins, a woman Walker professed not to know, did not fare as well. Authorities convicted her of sending the sword to Gilmore. She received a five-year prison sentence and was held briefly before admitting her guilt. She promised to be loyal and received a pardon from President Lincoln.

Old Noah joined his son in death in 1874.

Capt. Ned Alfriend was court-martialed on charges of being absent without leave and disobeying orders. Cashiered in February 1865, the war ended before appeals to overturn the conviction were reviewed. Alfriend returned to his native Richmond, where he prospered in the insurance business and achieved notoriety as a playwright. His 14 works include the 1892 military drama “Across the Potomac,” which New York City theater critics blasted as a sentimental glorification of overly virtuous Southerners and bloodless Northerners. The cast of characters included one “Capt. Noah Walker.”

References: Kelbaugh, Ross J., Primary Record Documentation: Lt. Noah Dixon Walker 44th Virginia Infantry Regiment C.S.A.; The Sun, Baltimore, Md., Feb. 4, 1874; The Evening Sun, Baltimore, Md., Sept. 22, 1935; 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules; Letter from Lt. Noah Dixon Walker to his father, Feb. 10, 1863, copied from a manuscript presented to the Maryland Historical Society in 1945 by Henry M. Walker; Walker, “Lieut. Noah Dixon Walker 44th Virginia Regiment C.S.A., Maryland Historical Society; Noah D. Walker military service record, National Archives; Union Provost Marshals’ File Of Paper Relating To Individual Civilians, National Archives; New York Times, Nov. 26, 1864; Bradford Reporter, Towanda, Pa., Dec. 15, 1864; Fall River Daily Evening News, Fall River, Mass., Jan. 12, 1865; Official Records; Encyclopedia Virginia; The Theatre (May-June 1892); Figaro (November 1892).

As part of the Civil War Centennial generation, Ross J. Kelbaugh has had a passion for collecting and researching early American photographs ever since he acquired his first Brady carte de visite while in the seventh grade in 1962. His publications include Introduction to Civil War Photographs, Introduction to African American Photographs, 1840-1950, and Maryland’s Civil War Photographs: The Sesquicentennial Collection.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.