By Jason Lee Guthrie

The pioneering work of historians such as Robert Taft, William Welling and Bill Frassanito has contributed to more than just the history of photography as a medium. It has helped establish the photograph as a valuable primary source on par with textual records like news articles and personal correspondence.

Historical photographs can provide valuable information about the topography of a battlefield, the architecture of a city, and the day-to-day life of a bygone age. In 19th century America, many stereographs and cartes de visite produced for a mass audience carried clues, not only in the image itself, but also imprinted upon the image mount. The copyright imprint, comprised of the words “Entered According to Act of Congress” followed by the year, registrant name and location information, are a window into a wealth of historical evidence.

Decoding that evidence can be difficult without an understanding of early American copyright law and its relationship with politics, culture and technology. This article considers the period between the first American Copyright Act in 1790 and the major revision of 1909, bracketing the “long” 19th century by a decade on either side.

The 1790 act based its authority on a clause in the U.S. Constitution and allowed copyright protection for any “map, chart, book, or books.” Just after the turn of the century in 1802, Congress acknowledged the unique nature of copyright in image-based mediums by explicitly adding protection for “historical and other prints.”

The next major revision occurred in 1831 at the lobbying of Noah Webster, who sought to double the initial copyright term from 14 to 28 years, and add other provisions for the estates of copyright holders after their deaths. Later that same decade, in a moment of historical serendipity, Samuel F. B. Morse happened to be in France seeking a French patent for his telegraph in early 1839 just as Louis Daguerre announced the discovery of his revolutionary image capturing process. Morse and Daguerre shared their discoveries with each other. Upon his return to New York, Morse lectured on daguerreotypy, which led to rapid diffusion of the technology in America. Yet, it would take years for this early image capturing process to mature into what we now call photography, and photography would not be explicitly added as a copyright protected medium until just before the end of the American Civil War.

Many factors contributed to this disconnect between technological innovation and legislative reform—a dynamic that continues to define copyright law today. It is important to remember that while, in theory, any image can be registered for copyright, only those images with mass appeal are truly vulnerable to infringement. No reason exists to infringe upon a copyright unless the infringer stands to profit by doing so.

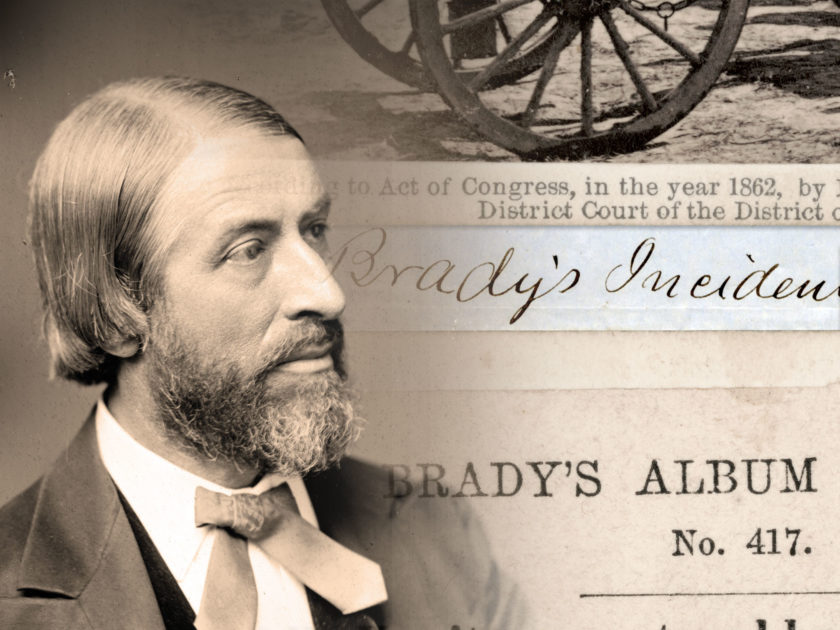

Some particularly popular daguerreotypes were prepared for mass production as lithographic engravings, a process that clearly fell under the 1802 law. As American daguerreotypists transitioned to a photographic process utilizing a wet-plate collodion negative, mass production of images became more cost-effective and more in demand. Photographers such as The Langenheim Brothers, Jeremiah Gurney and Mathew Brady seemed to assume that photographic images would enjoy the same protection as prints made from daguerreotypes. They adorned their work with the copyright imprint at least as early as 1854. Not until the convergence of technology, economy and publication that gave rise to immensely popular formats, such as the stereograph and cartes de visite, did copyright protection for photography become truly necessary.

The war itself further delayed photographic copyright legislation. One of the last pieces of legislation signed by President Abraham Lincoln before his assassination was an amendment to the copyright act on March 3, 1865 that mandated it “extend to and include photographs and the negatives thereof.” Although the popularity of stereographs and cartes de visite exploded at the onset of the war, copyright reform was understandably not a priority for Congress, with battles raging at times just miles from the Capitol.

Copyright records held at The Library of Congress and the National Archives can be a historian’s goldmine. But an understanding of the copyright registration process is helpful to navigating these holdings.

Prior to 1870, copyright registration was done in person at local district courts. Of these, the Southern District of New York was by far the most prolific. Consider that the years 1845-1870 reside in a single volume for the District of Columbia, while a typical New York volume during this period might fill up in three to five months. To register, the applicant would fill in a blank form with their name, the date, the item title and other information. The clerk of court would retain a copy of that form, as well as enter the entire text of the form by hand into the current volume of the copyright register. Additionally, applicants might submit some evidence of the registered piece, such as a book’s title page or a sheet torn from a playbill. Photographers such as Brady and Alexander Gardner adapted this practice to the photographic medium, submitting a wide variety of printed matter including handwritten notes, cartes de visite labels, and advertisements as evidence of their work. Brady and others also utilized the back label of their mass-market images to further assert their copyright and discourage infringement.

Lincoln’s legislation granting photographic copyright had what was likely an unintended consequence. In Wood v. Abbott (1866), Federal District of New York Judge J. Shipman ruled that if it was necessary for a law to be enacted specifically granting photographs copyright status, then photographs could not be “prints” as intended by the previous law. This invalidated copyright claims in any photograph published before the March 3, 1865 amendment, including all but the very last images of the Civil War. An article in Humphrey’s Journal called this development “an interesting example of how the changes and advances in science compel changes in the law.”

This interesting example highlights the cultural component of copyright. While copyright is first a legal construct, with specific formalities and parameters mandated by law, in practice, copyright law has its own social norms and customs. Beyond legal protection, registering a work for copyright carries a certain cache of legitimacy, both for the work itself and for its creator. Copyright litigation is expensive and time consuming; printing a copyright claim on an image is not. Mid-19th century photographers were aware of rampant piracy, and most participated in it. If the printing of a copyright notice dissuaded even one potential pirate, it was worth the ink to print it. And when it came to the point, if copyright was not able to discourage piracy, at least the photographer’s name would be imprinted next to the image.

When Ainsworth Rand Spofford became the Librarian of Congress in 1864, he began work on a notable campaign of copyright reform that ultimately resulted in the Copyright Act of 1870. Among many other specific reforms, the 1870 act centralized copyright registration in the Library of Congress. It should come as no surprise that records after this date are more complete, although Spofford tried valiantly to cajole and censure the various District Courts in an effort to get older records sent to Washington. Many of those records did eventually make their way to the nation’s capital, and are available to interested researchers to this day.

Photographic copyright is an interesting case. The fact that photographers of the medium’s first generation actively registered their work without specific guidelines did set precedent. Thomas Edison, for example, took a similarly aggressive strategy with intellectual property protection both on his patentable inventions and his copyrightable phonographs and films. A comparison between major copyright cases of the late 19th century may also be instructive of the influence that active registration had for image-based work. Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884) is significant not only for reinforcing the legality of copyright protection for photographs, but also for what it reveals about the status that photographers had achieved by the late 19th century. At issue in the case was a portrait of Oscar Wilde taken by photographer Napoleon Sarony, and unlawfully reproduced in an advertisement by the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company. Justice Samuel Miller wrote an unanimous opinion for the court that referred to the defendant as “the author, inventor, designer, and proprietor of the photograph.” This language evokes both sides of the author and inventor dichotomy in the Constitutional clause, weds them with the intentionality of design, and legitimizes the marriage of that statutory construct with the professional status of proprietorship found in the amendment of 1865.

Conversely, White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v. Apollo Co. (1908) found that manufacturers of player piano rolls did not have to pay royalties to the composer of the song imprinted on the roll. While Justice William Day acknowledged the plaintiff’s argument that music “is intended for the ear as writing is for the eye,” he and the rest of the court were not persuaded that musical composition deserved the same authorship status awarded to photography in the Sarony decision. Instead, the rolls were determined to be a part of the machinery of the player piano, and therefore could not infringe upon the sheet music in which the copyright for the original composition was vested. The Copyright Act of 1909 superseded this decision, and mandated a compulsory license for the mechanical reproductions of musical works. However, historical factors that resulted in legitimizing protection for image work over audio still show a vestige of influence today.

References: Taft, Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839-1889; Welling, Photography in America: The Formative Years, 1839-1900; Frassanito, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time; Frassanito, Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day; Frassanito, Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns, 1864-1865; Zeller, The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography; Gillespie, The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology; Patry, Copyright Law and Practice, Volume 1; Roberts, “Records in the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress Deposited by the United States District Courts, 1790-1870,” The Papers of The Bibliographical Society of America 31, no. 2 (1937); Humphrey’s Journal, July 1, 1866; Darrah, Cartes de Visite in Nineteenth Century Photography; Guthrie, “Ill-Protected Portraits: Mathew Brady and Photographic Copyright,” Journalism History 45, no. 2 (June 2019); Ostrowsk, “‘The Choice of Books’: Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the Ideology of Reading, and Literary Collections at the Library of Congress in the 1870s,” Libraries & the Cultural Record 45, no. 1 (2010); Decherney, Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet.

Jason Lee Guthrie is a media historian interested in the intersections of creativity and economics. He has specific interests in the creative industries and intellectual property law. A proud graduate of The University of Georgia, his dissertation “Authors and Inventors: The Ritual Economy of Early American Copyright Law” won honorable mention for the Margaret A. Blanchard Dissertation Prize, awarded by the American Journalism Historians Association in 2019.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.