By Paul Russinoff

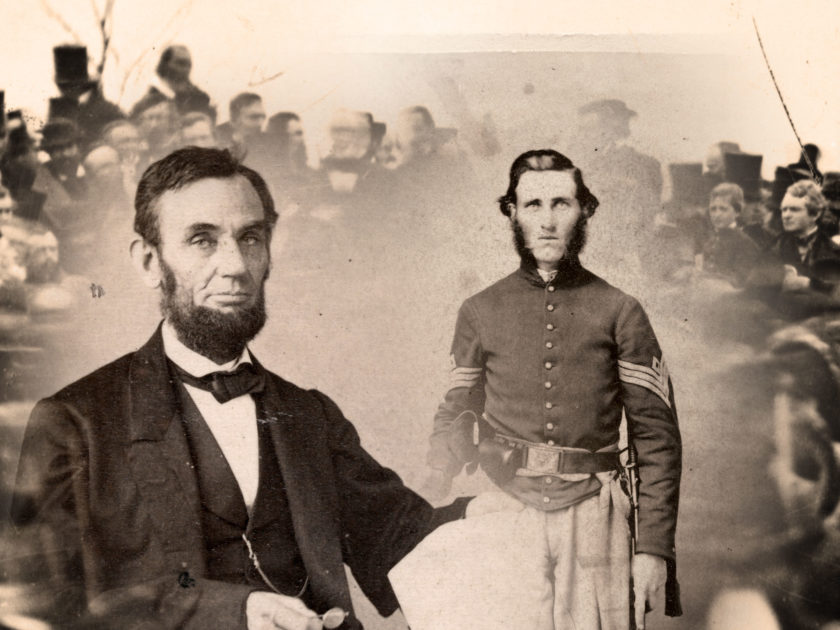

A messenger approached Sgt. Paxton Bigham with a document and a few words that implied immediate action: “A telegram for the President.”

Paxton took the paper, turned and tapped on the door in front of him. A moment later, he handed it to President Abraham Lincoln. The chief executive stood and read it, and then sat in the well-appointed bedroom from which he had just emerged, leaving the door ajar.

The dutiful sergeant watched as Lincoln pondered the document. After a pause, Lincoln rose, walked towards Paxton and spoke to him in a familiar, tender tone, “This telegram is from home, my little boy has been very sick but is better.” He referred to his son, Tad, who suffered for some days with fever and a rash.

The good news buoyed the careworn president at a historic moment. The following day, Nov. 19, 1863, he planned to deliver an address at the dedication of the new Soldiers’ Cemetery, less than a mile away from his lodgings in downtown Gettysburg. And Paxton, his assigned bodyguard during the visit, stood ready to protect him.

Paxton’s Gettysburg experiences sit like bookends flanking the momentous battle. On one side was his assignment to the president on the solemn occasion of honoring battle dead; on the other side, his participation in several actions leading up to the 3-day engagement.

Paxton grew up in Adams County, Pa. His life journey had begun 22 years earlier and a few miles southeast of Gettysburg in Freedom Township. Born the fifth of six children to farmer James Bigham and his wife Agnes, his parents named him Hugh Paxton Bigham. Family and friends called him by his middle name, a tribute to William Paxton, a local Presbyterian minister. Young Paxton grew up with his four brothers and a sister in unremarkable circumstances until the spring of 1854, when his father lost a battle with bronchitis. Upon his death, his two farms passed to three sons. James Jr. received one. Paxton and his youngest brother, Rush, received the other.

Paxton did not last long on the farm. A few years later, he left to work as a clerk in a dry goods store up the road in Gettysburg. Maybe he never warmed up to farming, or perhaps he had started working too young and wanted to sow his wild oats. Whatever the reason, he eventually parted ways with Gettysburg, and struck out for Ohio. But his western adventure did not last and he returned by 1860.

When the war came the following year, Paxton did not answer calls to enlist. He passed again in 1862, despite hostilities coming within 50 miles of home when Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia invaded the north and were stopped at the Battle of Antietam.

Paxton responded differently when Lee launched a second invasion in 1863. On June 16, Paxton traded his clerk’s pencil for a carbine. In doing so, he answered two recent proclamations. The first, issued on June 12 by Gov. Andrew Curtin, called for volunteers to defend “our home, firesides and property from devastation.” The second, issued on June 15 by President Lincoln, established enlistment quotas: 50,000 Pennsylvanians and 50,000 more from surrounding states.

Curtin formed two new military departments in the Keystone State, one in the east and another in the west. He placed the eastern half, the Department of the Susquehanna, under the command of the able Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch, who assigned commanders to his subdistricts. One of them, career army officer Maj. Granville O. Haller, defended Adams and York Counties and esablished headquarters in Gettysburg.

Haller had at his disposal a trio of militia organizations, each composed of men from very different circumstances. Students from Gettysburg College joined Company A of the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment. City slickers from Philadelphia enlisted in the tony First Troop City Cavalry. And, 92 Adams County men and boys formed Bell’s Adams County Cavalry, a company of independent scouts organized by farmer-turned captain Robert Bell.

The fourth man to sign his name to Bell’s roster was Paxton. His high place in the order suggests his eagerness to defend his patch of farmland. He enlisted as first sergeant, indicating a favorable standing among peers and superiors.

Scouting the Enemy Turns Deadly

A week later, on June 23, Maj. Haller mustered Paxton and his comrades into federal service for six months. The troopers wore fresh uniforms and carried Colt revolvers and Sharps or Burnside carbines. Some received government horses, while others, including Paxton, furnished their own animals, and were reimbursed by the federal government at their appraised value.

That same day, Paxton received his first assignment—and faced his first rebels. Capt. Bell ordered Paxton and a detail of four other troopers to scout 15 or so miles west of Gettysburg, in the vicinity of the Caledonia Iron Works, a manufactory owned by Congressman Thaddeus Stevens.

Meanwhile, another detachment of soldiers moved towards the iron works on a collision course—about 40 veteran troopers of the 14th Virginia Cavalry. The rebels arrived first, and sent militia guarding the works skedaddling into nearby woods. Paxton and his comrades happened on the scene about this time, and quickly reversed course with the Confederates in hot pursuit. The Virginians kept on and encountered more militia—or bushwhackers depending upon one’s point of view—hidden in the thickly wooded area. According to one lieutenant in the 14th, shots frequently rang out, in one case with deadly results when one of his men, Pvt. Eli Amick, suffered a mortal wound. Some claim Amick to be the first casualty of the Gettysburg Campaign.

Paxton and his comrades escaped unharmed and returned to Capt. Bell. A few days later, on June 26, Bell’s boys encountered more Confederates. That day, they rode out of Gettysburg along the Chambersburg Pike at the head of the newly arrived 26th Infantry, which included the Gettysburg College students. The column halted about three miles west of town near Marsh Creek, threw out a picket line, and set up camp. Capt. Bell and some of his scouts rode ahead and spotted a column of the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry coming up the road.

Bell acted quickly. He dispatched a trooper to Gettysburg to alert Maj. Haller, and then galloped back to camp and reported what he saw to the colonel of the 26th, William S. Jennings. By this time the Virginians had gobbled up the picket and closed in on the camp. Jennings, in consultation with Bell, ordered everyone back to town. The move may have saved their skins, but it left Maj. Haller with no options but to abandon Gettysburg to the Virginians.

While Gettysburg’s terrified citizens packed up their belongings and livestock and headed east, Haller’s forces fell back as rainy weather turned the retreat into an exhausting two-day mud bath.While Gettysburg’s terrified citizens packed up their belongings and livestock and headed east, Haller’s forces fell back as rainy weather turned the retreat into an exhausting two-day mud bath. They regrouped in York and pondered their next move.

They did not have long to wait. On June 28, Confederates descended on York. Haller fell back a dozen miles to Wrightsville, and deployed his men to either defend or destroy a key railroad bridge that spanned the rain-swollen Susquehanna. Bell’s scouts, including Paxton, rode on a reconnaissance in the vicinity of Wrightsville when they encountered the rear guard of an enemy brigade commanded by Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon.

The Confederate invaders greeted them with a pair of shells and a flurry of bullets that wounded a few horses and one trooper, who fell into enemy hands. A second unhorsed man evaded escape by hiding out in a nearby house. Bell decided further resistance was futile, and ordered his bugler to sound the retreat. The scouts withdrew, commandeered a raft, crossed the river and rendezvoused with militia on the other side of the bridge in the town of Columbia.

The rest of Haller’s command fired the bridge, leaving Gordon and his Confederates on the Wrightsville side of the river.

Maintaining law and order — and capturing Rebs

The Confederates managed to find another way across the Susquehanna and continued the advance. Less than three days later, full-scale fighting erupted at Gettysburg. While Northern and Southern forces slugged it out in the woods and fields north of town and later at Culp’s Hill, Little Round Top and other geographic spots soon to join the American lexicon, Bell’s scouts remained in Columbia. As news of the battle filtered in, Paxton likely cast his thoughts to family and friends left behind, especially his fiancée, Elizabeth McCright. In hindsight, he needn’t have worried for they were unharmed.

After the battle ended in favor of the Union, the beaten Confederates headed south to Virginia. Bell’s scouts rode north to Harrisburg, where the men refitted and consolidated into Company B of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Company B returned to Gettysburg in August to act as provost, and found cleanup efforts well underway to deal with devastation and gore. Some 8,000 human remains and 5,000 dead horses and mules lay on or slightly below the surface of the town and surrounding farms.

As provost guard, Paxton and his comrades arrested deserters and stragglers of both armies, gathered salvageable military arms and equipment from the battlefield, policed burials, and protected the site from relic hunters and others who did not have legitimate reason to be there. In one grisly instance, they arrested some local men who were digging up freshly interred bodies and removing their clothes to use as a raw component at a local paper mill.

Paxton related one story of how he came upon a suspicious brush pile, which concealed men in hiding. He called on the men to show themselves, or else he would fire. He reached for his holster, but discovered his revolver missing. It had fallen out earlier. Fortunately, the men—Confederate deserters—did not need further encouragement and surrendered. Paxton escorted them to the authorities to be processed.

Guarding the President on Hallowed Ground

Four months later, Paxton participated in the assignment of a lifetime—guarding the president. How he came to be selected involved, as so many events in life, a matter of time, place and character. Company B’s provost duty made it the natural choice to act as a security detail to patrol the grounds during the dedication ceremonies for the Soldiers’ Cemetery scheduled for November 19. Paxton’s rank as first sergeant suggests he had the confidence and admiration of Capt. Bell.

On the evening of November 18, a train carrying the president, Secretary of State William Seward and their entourage pulled into Gettysburg. Among the dignitaries who met them at the station included the distinguished statesman and keynote speaker Edward Everett, and David Wills, the local banker and brainchild of the cemetery. It is likely Paxton also stood on the station platform. It is easy to imagine Lincoln, courteous by instinct and a savvy politician by experience, acknowledged Paxton’s presence with a smile, affirmative nod or handshake.

The eminent group left the station and walked through town, its streets filled with visitors gathered for the ceremony. They made their way a few blocks for dinner at the stately Wills residence, where Gov. Curtin and other guests joined them. After the meal, the party broke up. Seward left for the home of Gettysburg Sentinel editor Robert G. Harper to spend the night. Lincoln and Everett remained at the Wills house.

Outside the Wills home, bands serenaded the president and a large crowd called for a speech. A compliant Lincoln appeared at the door and delivered impromptu remarks before returning inside. He then retired to his bedroom on the second floor. Paxton assumed his position outside the door and his younger brother, Rush, who also served in Company B, guarded the front door.

About this time, the telegram about the condition of Thomas “Tad” Lincoln arrived. The 10-year-old boy had suffered from a rash and fever for the better part of a week, and there can be no doubt that the situation weighed heavily on the president’s mind. That Lincoln shared his concern and relief with Paxton is emblematic of Lincoln’s inclusive manner.

Although Lincoln nodded his head during the delivery of nearly every sentence in the short address,” Paxton told the interviewer, “he made only one gesture during his speech. As he finished there was silence and then applause after which people crowded to the platform to congratulate him.

Paxton recalled years later that Lincoln then turned back inside his room, sat by a desk, and looked over a manuscript. Paxton assumed it to be the draft of the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln asked for ink and paper and went to work, Paxton believed, “copying his speech, for it is well known he had prepared his speech in the White House ten days before, but as I understood it he was revising sentences so as to improve the force and strength of this address.” The President continued for some time in silence with the exception of the scratch of a pen nib on paper. Lincoln eventually came to the door and asked Paxton, “Guard, do you know where Secretary Seward is stopping? I want to go there for only a few minutes.”

Paxton revealed that Seward lodged only a few doors away. Before long, Paxton, with Lincoln in tow, arrived at the Harper home, and waited outside the door while the two leaders likely discussed the next day’s events. About this time a glee club from Baltimore, known as the National Musical Association, serenaded the president and secretary. Lincoln eventually appeared at the door and informed Paxton, “I want to go to my room, you clear the way and I will hold on to your coat.” In another version of this story told by Paxton, “Mr. Lincoln walked behind, taking hold of my ‘wammus,’ as he called my soldier blouse.” In fact, a wamus is an ancient European term for a rugged work jacket.

Paxton guided Lincoln back to the Wills House, and spent an uneventful night on guard. Early the next morning, Lincoln and Seward toured the battlefield by carriage, and then returned to the Wills house for a parade to the Cemetery and the dedication ceremony.

Paxton stood within a few feet of the platform from which Lincoln delivered his address. “When the president arose,” recorded a reporter who interviewed Paxton, “the audience moved about in an effort to get nearer the platform and the first part of the address was not heard clearly by the audience. Although Lincoln nodded his head during the delivery of nearly every sentence in the short address,” Paxton told the interviewer, “he made only one gesture during his speech. As he finished there was silence and then applause after which people crowded to the platform to congratulate him.”

After the speech, Lincoln returned to town, with Paxton, and attended a service at the local Presbyterian Church. He greeted 70-year-old John Burns, already known across the Union as the Hero of Gettysburg for leaving his local farm and fighting Confederates until multiple wounds knocked him out of action. Lincoln’s visit ended at the train station, where he and his party departed about 7 p.m.

There is no evidence that Paxton ever again met the president.

Returning to Civil Life

In February 1864, Paxton ended his 9-month enlistment suffering from fever. He never received remuneration for his military service, other than a $41.31 allotment for clothing. Still, he managed to pay $300 to pay a substitute to stand in for him after the government mailed him a draft notice later in the year.

Paxton followed the lead of many young men who married and settled down after the end of their army life. In March 1864, he married his fiancée, Elizabeth. They purchased a home and general store in Green Mount (now called Greenmount), a village about five miles south of Gettysburg, and started a family that grew to include seven children.

In January 1865, during the war’s final months, Paxton received an appointment as postmaster of his new hometown. He became prominent in local business and civil affairs, including the Grand Army of the Republic. He also suffered sorrow when his brother and comrade-in-arms, Rush, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1874, and in the deaths of four of his children. Three daughters lived to adulthood, one of which married and produced grandchildren.

In 1913, the post office closed, prompting Paxton’s retirement. He and Elizabeth sold their home and relocated close to a daughter who resided in Chambersburg—another Pennsylvania town that had experienced the horrors of war firsthand. Two years later, Elizabeth passed away, and Paxton moved to Altoona to live with his youngest daughter. He stayed there until his death from pneumonia in September 1926. Paxton was 85 years old. His remains rest alongside Elizabeth’s about 10 miles west of Gettysburg in Lower Marsh Creek Cemetery.

Paxton’s long life, on balance, might be considered unremarkable. He experienced the joys and sorrows common to many men and women of the time. That is, with the exception of one autumn day in 1863 when the safety of our 16th president, and the delivery of the most important speech in American history, rested in his hands.

References: Horner, Sgt. Hugh Paxton Bigham: Lincoln’s guard at Gettysburg; Altoona Tribune, Altoona, Pa.; March 10, 1926; 1850, 1860 U.S. Census; Adams County Registration of Deaths; Coddington, “Pennsylvania Prepares for Invasion, 1863,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies (April, 1964); Richmond Dispatch, April 5, 1896; H. Paxton Bigham military service and pension files, National Archives; Mingus, Flames Beyond Gettysburg; Willis, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America; Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage.

Paul Russinoff is a Senior Editor of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.