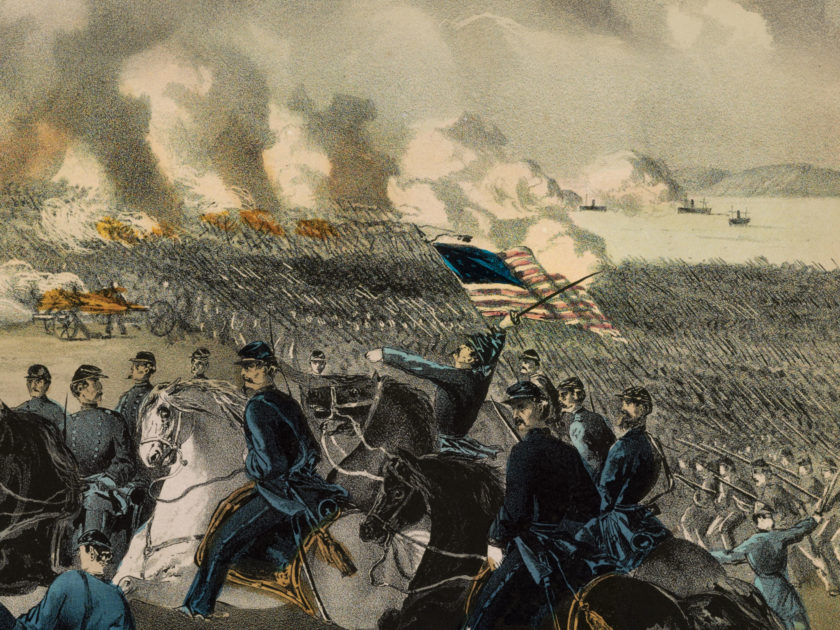

Common themes run through the discussions of momentous battles, and Shiloh is no exception.

Considered from a strategic angle, the bloody engagement fought on April 6-7, 1862, near Pittsburgh Landing in western Tennessee, possessed little military significance. Author Shelby Foote reflected on the resemblance of the Confederate battle plans to those used by Napoleon at Waterloo in his classic, The Civil War: A Narrative: “Yet Waterloo had settled something, while this one apparently had settled nothing. When it was over the two armies were back where they started, with other Waterloos ahead.”

In the very next sentences, Foote visited another familiar theme, the role of the soldier: “In another sense, however, it had settled a great deal. The American volunteer, whichever side he was on in this war, and however green, would fight as fiercely and stand as firmly as the vaunted veterans of Europe.”

These American soldiers also fell as quickly as their counterparts a continent away. The accepted total of Shiloh casualties, 23,746, is a remarkable figure in context to the times. The battle with the largest number of casualties prior to Shiloh, First Manassas, totaled 4,878 souls. Shiloh’s grim record, which exceeded all previous American wars combined, did not stand long. Eight months later another Tennessee battle, Stones River, ended with overall losses of 24,645.

These American soldiers also fell as quickly as their counterparts a continent away. The accepted total of Shiloh casualties, 23,746, is a remarkable figure in context to the times. The battle with the largest number of casualties prior to Shiloh, First Manassas, totaled 4,878 souls. Shiloh’s grim record, which exceeded all previous American wars combined, did not stand long. Eight months later another Tennessee battle, Stones River, ended with overall losses of 24,645.

The public, through official reports, newspaper accounts and letters home, learned the enormity of Shiloh’s casualties almost immediately. The isolated location of the fighting fueled a humanitarian crisis, as caregivers raced to the scene to save the sick and wounded. The battle also prompted story and song, as Americans came to grips with wholesale death on an unimaginable scale. Less than a month after the fighting ended, poet Clarence Butler’s The Battle at Pittsburgh Landing appeared in newspapers. The first lines set a dramatic scene for the catastrophic losses:

A roar as though a million hells

Were howling out their shame;

Broad leagues of heaven-affrighting yells;

Square miles of screaming flame;

A horrid purpling of the grass;

A quenching of the sun;

Red swathes of limbs in writhing mass;—

Almost two decades later, writer Ambrose Bierce, a Union army veteran who participated in the second day’s action, recorded his observations of the dead in What I Saw of Shiloh: “Some were swollen to double girth; others shriveled to manikins. According to degree of exposure, their faces were bloated and black or yellow and shrunken. The contraction of muscles which had given them claws for hands had cursed each countenance with a hideous grin. Faugh! I cannot catalogue the charms of these gallant gentlemen who had got what they enlisted for.”

Here, we look upon representative faces of those who participated in the battle, and tell their stories.

“We Sounded Their Reveille by Opening Fire on Them”

In the wee hours of April 6, a patrol composed of Companies B, E and H of the 25th Missouri Infantry made their way through their own picket line and passed into enemy territory in search of Confederates. One man present for duty, 22-year-old Pvt. Addison Newell Glenn, served in Company H. He and his fellow Missourians spotted a trio of gray horsemen about 5 a.m. and traded shots. About 15 minutes later in a field that belonged to farmer John C. Fraley, a skirmish erupted when soldiers from the 3rd Mississippi Infantry Battalion opened fire.

Depending on one’s point of view, the Missourians had either got more than they bargained for, or had started the Battle of Shiloh.

An officer in the 25th took an expected upbeat view in the regimental history, “We sounded their reveille by opening up fire on them, and it was not many minutes before that whole army of 65,000 men were in motion and the woods were full of them. We stood long enough for most of the men to use up their forty rounds of ammunition, which, with the hot volleys they turned loose on us, gave good and convincing warning to our slumbering army to ‘fall in’ on short notice.”

Glenn, an Ohio native who had moved to Missouri before the war, survived the battle. He went on to become a first lieutenant and ended his service in 1864 with the 1st Missouri Engineers. Back in Missouri, he married and raised a family in Mound City, where he entered business and served as the city’s postmaster. He died in 1905.

Briefly in Command

A month before the battle, 2nd Lt. Squire Austin Wright received his captain’s bars and a transfer from Company C to H of the 55th Illinois Infantry. The men in his new company did not approve, preferring one of their own. But Wright was a favorite of the regiment’s colonel, and the transfer remained.

Wright led his new company at Shiloh. He suffered a wound early on from a random bullet during a lull in the action. He refused to go to the rear. Later, as he led his men forward, he received a second, serious wound that took him out of the fight. The injury proved mortal, and he died May 12, 1862, at age 23. He holds the grim distinction of being the highest-ranking officer of the regiment who died as a result of the battle.

Finding Rebs

In September 1861, John Keppel had been a soldier all of four months when he wrote home, “I have traveled over a great Deal of ground after Rebels but could not find them. But there is plenty of them Som Ware that is Shure. We will have a chance to find them Soon I think.”

Keppel, a 21-year-old private in the 2nd Iowa Infantry who had come to America with his family from Holland as a boy and settled in Keokuk, soon found the rebels. A few months later at Fort Donelson, Keppel survived the fight that cost the regiment 197 casualties.

Then came Shiloh. Somewhere in the desperate fighting in the sunken road at The Hornet’s Nest, a bullet tore into Keppel’s right knee. Medical personnel evacuated him to St. Louis for treatment. According to family tradition, Keppel refused to have the mangled limb amputated. Gangrene set in and he slowly succumbed to its effects. Two of his sisters made it to his bedside before he died. Each woman later named a son John in memory of the favorite brother.

Keppel’s comrades fought on through the end of the war. The 2nd holds the grim yet proud distinction of being included on the list of the Union’s “Three Hundred Fighting Regiments” for its high casualty rate.

Move Over, John Burns

A report in the June 16, 1864, edition of the Evansville Daily Journal sheds light on this photograph, which its owner sold to raise funds for his own care. As the story went, “John Hicks is one of the most remarkable men of our day. A soldier of three wars—he was still in the field at the age of 82. He was born at Flemington, N.J., was raised in Easton, Pa., and worked at his trade in Reading. For the past 20 years he has lived in Indiana. He went into the army in the war of 1812; was again a soldier in 1832 in the Black Hawk war; and in 1860 (being then over 80) he volunteered for three years in the present war, and was enrolled in the 58th Indiana. He was at the Battle of Shiloh, and had a son over 60 years of age, killed there. He has lately been discharged, as somewhat disabled. (His papers prove these facts.) He stands firm and erect, has perfect use of his sight, speech and hearing; uses no cane, and hardly cares to sit down. Such vigor is wonderful.”

The report added, “a man whose example and patriotism should shame the peace sneaks, and the thousands of stout, able-bodied stay at homes who are determined that the war shall be prosecuted and the rebellion put down if it takes the last male relative themselves and their wives possess.”

No federal or other public records have been found to support the Journal’s reporting. If true, John Burns of Gettysburg fame may have met his match.

Dodging “The Big Ones”

During the second day of the battle, 1st Lt. Eddy Ferris and his comrades in the 14th Wisconsin Infantry charged and captured a rebel battery three times, only to abandon the capture due to a lack of support. As the men formed for a fourth charge, according to a historian, “The regiment drew the concentrated fire of all the enemy’s guns within range. Shell, grape and solid shot swept over and about them with shriek, hiss and roar, which only one who has been there can appreciate.” The colonel of the 14th, Lyman M. Ward, passed along the line and cautioned his men to remain steady and not to dodge incoming projectiles. “Just then a perfect tornado of iron and lead swept over their heads. Every man and officer involuntarily dodged,” recounted the historian, who added that Ferris turned to his commander and said, “But Colonel, when they shoot a cooking stove right past a man’s ear, can’t he dodge just a little?”

The historian continued, “Well, yes,” said the Colonel, “if it’s a big one, dodge just a little, about as much as I did.” Presumably, Ferris followed orders. Five minutes later, the Wisconsin man charged for a fourth time and captured the battery for good.

Ferris suffered a minor wound during the fight and went on to become the regiment’s lieutenant colonel. He survived the war and moved west, dying in Montana in 1908.

Combat-Ending Injury

The 8th Illinois Infantry went into action near Shiloh Church early on the first day of the fight, and remained engaged for the better part of both days. The regiment started with 478 officers and men and lost 132, including Pvt. Augustus Anderson of Company H. He suffered a severe wound in his hand that effectively ended his combat career. He spent the rest of the war as a teamster, an ambulance driver and a nurse. He mustered out in 1866 and filed for a pension in 1874.

From Shiloh to Washington

The after-action report of the 70th Ohio Infantry paints a picture of a regiment caught up in a series of fiery encounters with the enemy, and without any real opportunity to take the initiative. When the engagement ended, the regiment mustered some 500 muskets, about a hundred less than they brought into the battle. Casualties included Pvt. Samuel R. Blair of Company A, who suffered a thigh wound during the confusion and chaos of the first day.

A farmer before the war, the rigors of Shiloh and other operations compromised Blair’s ability to fight. His role with the 70th ended with his transfer to the 7th Veteran Reserve Corps in January 1864. The regiment performed guard duties in Washington, D.C., and participated in the defense of the capital when Confederate forces commanded by Lt. Gen. Jubal Early threatened the city in July 1864.

Blair survived the war and eventually settled into the farmer’s life in Indiana. He died in 1919 at age 78.

“He Lived Twelve Days and Suffered Much”

According to a capsule history of the 6th Tennessee Infantry, organized in May 1861 in the eastern part of the state, the regiment “was first engaged at Shiloh, having to endure the trial of a severe artillery fire before being engaged. About 11 o’clock of the 6th it was ordered to charge a battery, which it did in gallant style, meeting with a terrific fire, which cut down 250 men. It did splendid work on both of those memorable days, losing over one-third of those engaged.”

The long casualty list included 20-year-old James K. Herron. He joined Capt. William M.R. Johns’ company of Tennessee volunteers, which became Company D of the 6th. At some point during the battle, he suffered a mortal wound and succumbed to its effects on April 19. “He lived twelve days and suffered much,” reported the Memphis Daily Appeal. “He leaves a large family of relatives and many friends to mourn his untimely death, but such was his faith and deportment, that they enjoy the consolation that he yet lives.”

A Trip to Camp Chase

Col. Andrew K. Blythe’s Mississippi Regiment marched into action about 8:30 a.m. on the first day, and fought on both flanks of the army. According to an after-action report, “Blythe’s Mississippi advanced to the left and attacked the enemy, and, wheeling to the right, drove one of the enemy’s batteries, with its support, from its position; but as it advanced upon the enemy Colonel Blythe was shot dead from his horse while gallantly leading his regiment forward to the charge.”

About 150 of Blythe’s boys became casualties. They included Sgt. Andrew Martin Chandler, pictured here with Silas, a family slave. Chandler suffered a wound, fell into enemy hands, and landed in the prisoner of war camp at Camp Chase, Ohio. Evidence suggests that Silas carried news of Chandler’s plight to the family in Palo Alto, Miss.

Chandler received a parole five months later and returned to his regiment. He went on to fight at the Battle of Chickamauga, where he suffered a combat-ending wound. Silas, who helped his critically injured master home, returned to the war with Chandler’s younger brother, Benjamin, a private in the 9th Mississippi Cavalry. The two men remained together until May 1865, when Benjamin Chandler surrendered at Washington, Ga.

Benjamin died in 1909. Silas passed away 10 years later at age 82 in September 1919. Andrew survived Silas by eight months. He died in May 1920.

Third Attack

Three days before the battle, Col. John Gordon Coltart assumed leadership of his new regiment, the 26th Alabama Infantry. The son of Scottish immigrants who had settled in Huntsville, Coltart had marched out of his hometown in May 1861 as captain of a militia company that became part of the 7th Alabama Infantry, and fought in Florida.

Now, a year later, he had his first opportunity to distinguish himself as a regimental commander. On April 5, he and his men arrived in front of the Union army’s encampment at Pittsburgh Landing, and spent the night on picket duty. At daybreak on the 6th, without sleep or breakfast, Coltart and his boys moved up to the main battle line. According to the regiment’s after-action report, ““In a few moments we were hotly engaged, contributing a full share to the driving back of the enemy. When the charge was made upon the lines and into the camp of the enemy the Twenty-sixth was among the first to penetrate them.” Following a tense hour exposed to an artillery duel, Coltart led his men on another successful attack. “The conflict was severe for a short time, when the enemy, falling back, moved to our left,” noted the official report.

About a quarter-hour later, the Alabamians moved into the edge of an open field and entered the Hornet’s Nest, where they encountered severe fire. At some point, a bullet or shell fragment struck Coltart in the heel, and he dropped back to have his wound dressed. He soon returned. According to his second-in-command, Lt. Col. William Chadick, “He was able to remain but a few moments. Seeing the exhausted condition of the regiment, he ordered, or rather advised me, to withdraw it from the field.” After Coltart departed, Chadick determined to fight on, and did so, until the original 440 men had been reduced to less than 200. Only then did the regiment withdraw.

Coltart eventually rejoined his comrades and served through the rest of the war, during which time the regiment’s designation was changed from the 26th to the 50th. He commanded on the brigade and division level, and suffered his second war wound at Atlanta in 1864.

In Huntsville after the end of hostilities, he served a 2-year stint as sheriff. Removed from office in 1867 and confined in a mental asylum, he died the next year at age 42.

Four Assaults, Severe Casualties

Bullets buzzed about Walter Virginius Crouch and his men in the 13th Louisiana Infantry as they struggled through an almost impenetrable oak thicket that came to be known as the Hornet’s Nest. The Louisianans advanced towards enemy lines scratched out of the tangled woods. “Four times the position was charged and four times the assault proved unavailing,” wrote the regiment’s commander, Col. Randall Gibson, in his after-action report. “We were repulsed. Our men, however, bore their repulse with steadiness.” Casualties ran high, and included Crouch. He emerged from the battle with a slight wound to his forehead—far less serious than many of his brethren.

Crouch, a native Virginian who had settled in New Orleans prior to 1861, went on to become a major on Gibson’s staff. He survived the war and returned to New Orleans, where he resided until his death in 1902 at age 80. He outlived three wives.

Bound for Camp Douglas

Details of how John T. Smarr fell into Union hands are not known. But the whereabouts of the corporal from the Confederate 9th Kentucky Infantry is—Camp Douglas, the Chicago prisoner of war camp. He remained there for about six months before he gained his released and rejoined his comrades. Smarr landed on the casualty list twice more during the war. He suffered a wound at Chickamauga in 1863, and was captured again during the 1864 Atlanta Campaign. Smarr surrendered with his regiment at Washington, Ga., in May 1865, made his way back to Kentucky and lived until 1897. He died at about age 60.

“Good by for Tonight”

The 14th Ohio Battery suffered heavy losses during the first day’s fight. All of its guns were left on the field. 50 horses were killed. 30 artillerymen were listed as casualties. The wounded included Pvt. William C. Hall, a peacetime carpenter who had enlisted the previous year at age 31. He suffered two injuries: A minor hip wound and a bullet through the shoulder that fractured a bone located close to an artery. A surgeon described the case as critical, for if any slivers of shattered bone nicked the artery, Hall would bleed to death.

The guns were recovered the next day. Meanwhile, Hall was transported first to a general hospital at Mound City, Ill., and later to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, where Hall’s life hung in the balance for weeks. During this time he exchanged letters with his wife, Augusta, back home in Austinburg, Ohio. Other women who came to the hospital to attend to wounded and sick husbands took William into their care and wrote letters for him, despite the misery they felt for their own circumstances.

Though Hall repeatedly asked his wife to visit, lack of travel money, the need to care for their young daughter, Julia, and, perhaps her firm belief in his recovery, kept her away. Still, she longed to be with him.

On May 5, 1862, she wrote a letter and closed with “Dear William, I wish I could take care of you tonight. I would if I could. Good by for tonight.” Hall never read her letter. He died on May 8 without seeing his wife or daughter.

“Charge! Charge! By order of General Grant!”

Arriving late in the evening after the first day of battle, Capt. James Curtis, Jr., and his comrades in the 15th U.S. Infantry crossed the Tennessee River and reached Pittsburgh Landing about 5 a.m. They went on to participate in the repulse of Confederate forces that ended in success for Union arms. The 15th and its brother regiment, the 16th, distinguished themselves in a charge against the rebel brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. S.A.M. Wood. According to a history of the 15th, an officer rapidly approached the regulars from the rear and cried, ‘Charge! Charge! By order of General Grant!’”

The regulars drove the enemy back. Curtis suffered a wound that kept him out of action for a month. It was the first wound for Curtis, the son of a former mayor of Chicago and an 1851 graduate of West Point who had served in the West prior to leaving the military in 1857. Curtis rejoined the regular army after the war began and received an assignment with the 15th.

After Shiloh, he participated in numerous campaigns and suffered his second war wound at the 1864 Battle of Atlanta. He also performed administrative tasks on several occasions, including a stint on the staff of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans. He continued in the army after the war, and retired in 1876 after a fall from a horse. He left with a major’s brevet for Shiloh and Atlanta, and died two years later at age 48. His death was blamed on a cold, but a quote from a letter written after he retired and entered private life raises questions: “A change will not trouble me in the least. My tortures, physical and mental, have been beyond words. I have seen all my hopes and ambitions perish. There is nothing left living for.”

Death of the Color Guard

The boys of the 16th Wisconsin Infantry faced the battle’s first fire on the morning of April 6. Thus began an awful day that can be fairly described as a grim cycle of fighting overwhelming enemy forces, and stubbornly giving ground. “The rebel hordes were coming in,” reported one regimental historian, and “rolling up great columns like the waves of the ocean.” When hostilities ended, the casualty list totaled 254, including the regiment’s colonel and lieutenant colonel. Six members of the color guard lost their lives, four of whom are pictured here. All served in Company E. The senior member of the group, Sgt. Joseph L. Holcomb, about 42, hailed from New York. A carpenter by trade, he left behind a wife and five daughters. The other three young men, all privates, include Lewis E. Knight, a single farmer from Maine, Erwin L. Rider and Henry L. Thomas. The remains of all six were eventually buried in a semicircle around a flagstaff overlooking the Tennessee River.

“The Long, Dark Night of Rebellion”

After the rebel juggernaut drove the 16th Wisconsin Infantry and the rest of its brigade from its camp on the morning of the first day of the fight, officers and men fell back. They reformed along the rear of the camp about 8 a.m., and fought desperately to hold their position. About this time, the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, Cassius Fairchild, fell with a bullet in his thigh. Dragged to safety, surgeons preferred amputation. The wound, however, proved too close to the hip joint, and surgeons deemed an operation impossible. Transported to his family in Madison, eight long months passed before a doctor found and extracted the bullet, along with seven fragments of his uniform. Fairchild returned to duty in May 1863 and finished out his enlistment. He mustered out as colonel and brevet brigadier general in July 1865.

Three years later, while serving as a U.S. Marshal, the wound broke open and his condition steadily worsened. On Oct. 14, 1868, he married his fiancé, Mary Haney, despite his condition, which, by this time, had confined him to his sickbed. Ten days later, he died at age 38. Formal resolutions adopted on his passing included this tribute to his character: “We have lost an estimable companion, a true, trusted and valued friend; one who stood by the flag of his country amid the assaults of treason, throughout the long, dark night of rebellion.”

Frank’s Horse, Frank

Confederate command initially held the six-gun battery of the 1st Kentucky Light Artillery in reserve at the start of the battle The situation changed about 11:30 a.m. when the Kentuckians went into action. 1st Lt. Frank Patten Gracey, according to his family, dismounted his horse, also named Frank, to help the men train the guns on the enemy. While Gracey performed his duties and the fire rapidly escalated, Frank the horse trotted off and took refuge behind a mountain of baled hay. Frank “remained in perfect safety and enjoyed a banquet of hay during the engagement.” A half-hour later Union forces overran the battery and took the guns. Gracey escaped capture and so did Frank, the only horse in the battery to survive. Confederate forces later recaptured the cannon.

The fate of Frank the horse after the battle is lost to history. 1st Lt. Gracey survived the war and became a successful businessman in Clarksville, Tenn., where a Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp was named in his honor. He died in 1895 at age 60.

The Making of Major Reynolds

As darkness set in after the first day of battle, panic-stricken Union troops descended on Pittsburgh Landing in search of an escape. Half-crazed with fright, the demoralized, disorganized mobs were only intent on saving themselves. Some of these men attempted to board support vessels anchored in the Tennessee River.

On the Emerald, where about 350 wounded from fighting earlier in the day were housed, two guards stood posted. A captain clutching a pair of revolvers blocked the gangplank. On the hurricane deck above him stood a woman armed with a revolver and ready for action. She was Belle Reynolds.

Reynolds’ actions at Shiloh became the stuff of legend. She followed her husband, 2nd Lt. William Reynolds of the 17th Illinois Infantry, through the early days of the war. On the morning of April 6, Reynolds awoke to the sound of cannon balls howling over their camp at Pittsburgh Landing. Caught up in the confusion, she fled to the landing and eventually made her way to the Emerald. During the days that followed, she nursed soldiers until finally collapsing from exhaustion. Appreciative soldiers later honored her with a major’s commission and undying gratitude for her lifesaving efforts.

Belle went on to serve as a nurse after the Spanish-American War. She lived until age 96, dying in 1937.

Benumbed Brains and Partially Paralyzed Bodies

When the history of the 57th Illinois Infantry was published in 1886, one of the veterans thanked for his encouragement and information was Capt. William S. Swan of Company C. A popular officer, he had suffered a wound during the battle. Though his exact contributions to the book went unrecorded, he may have shared this recollection of the challenging night between the two days of the fight. In it, the arrival of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell with reinforcements for Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army is mentioned.

“All night long the chilling rain poured down upon us. The only comfort we had in our sufferings was the occasional defining explosion from the gun-boats on the river, and the scream of shells as they passed over our heads in a great arc, and bursted among the enemy. All night long the signal lights could be seen between Grant’s and Buell’s signal officers from bank to bank of the river. All through the night regiments from Buell’s army, which had crossed the river in transports, marched by us to take position in line for the morrow. Being without shelter, the cold rain soaked through our clothing to our partially paralyzed bodies; the brain was benumbed from cold and hunger; weak men gave away to despair, and strong men cursed the misfortunes that placed our cause in such a position. The rain ceased a little before daylight, and the morning sun shone clear and bright, as though the heavens was smiling upon us and our cause.”

Swan healed from his wound and went on to become very involved in regimental reunions after the war. He lived until 1895.

First and Last Fight

Among the 187 officers and men of the 57th Illinois Infantry lost during the first day’s fight was Isaac C. Seek, a private in Company K. A New Jersey-born peddler who had settled in Illinois before the war, the exact moment he was killed went unrecorded. It is possible that he died along the crest of a hill near the Hamburg and Savannah Road. “It was here that the regiment made its hardest fight, their first severe engagement. It was here their casualties were the greatest,” noted one report. “Their arms were the old Harper’s Ferry muskets, altered from flint locks, and became foul after a few rounds. Some of the men threw down their disabled muskets, picked up the muskets of their killed and wounded comrades, and renewed the fight.” Seek was about 32 years old. His wife, Susan, and son, William, survived him.

Raining Balls and Shells

During the second day’s battle, Capt. John McConihe of the 1st Nebraska Infantry observed, “Balls and shell fell upon us like rain. He added, “Most of the balls passed over us, a shell passing through the air with a howl like caterwauling. A ball whizzing by with a hum, whizzing, or a buzz, according to distance it was from ones ear, and musketry and grape cut boughs from the trees in all directions.”

But about 8 p.m., as he led his Company G into action, rebel lead found him. He wrote, “As the Nebraska 1st was advancing and repulsing the enemy, I received a minie ball in my left arm which passed entirely through and out the arm, just below the elbow, fracturing the bone and making quite a hole. I do not think I shall lose the arm but hope to be ready for duty again in a reasonable time.”

A New York attorney who had settled in Nebraska and served as the territory’s adjutant general before the war, he completed his recuperation in his hometown of Troy, N.Y., where he sits, left, with his brothers, William, center, a captain in the 2nd New York Infantry, and Samuel, right, the major of the 93rd New York Infantry.

McConihe did not return to his Nebraskans. He accepted an appointment as lieutenant colonel of the 169th New York Infantry, and later advanced to colonel of the regiment. He served in this capacity until June 1, 1864, during the Battle of Cold Harbor, when a rebel bullet found him again—this time through the heart. He was 29. McConihe received a promotion to brevet brigadier general the same day. A month later, military officials named a redoubt along the Petersburg lines in his honor.

At Bloody Pond

After spending the night camped at the north end of the battlefield, 1st Lt. William K. Haselwood and the 50th Illinois Infantry fought through the day, notably east of the Bloody Pond. At some point during the action, rebel lead hit him in the arm and caused a slight wound. A farmer born in Kentucky to English immigrants, Haselwood earned his captain’s bars for his conduct at Shiloh.

Though he saw his fair share of death during the war, a personal connection occurred in March 1891 when his half-brother, Sgt. Alvin H. Haselwood of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, died at Fort Riley, Kansas, of complications from multiple gunshot wounds received during the massacre of Native Americans at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. Haselwood signed for his late brother’s personal effects.

Haselwood died in 1916 at age 76. Two children survived him.

He Dared Lead Those Who Dared Follow

First Sgt. Irenus McGowan of the 29th Indiana Infantry personified the best of volunteer soldiers. One description noted, “Always found at his Post of duty and as brave as the bravest. He dared to lead where any dared to follow.”

McGowan proved his mettle during the fighting on the second day of the battle. “When within twenty or twenty-five miles of Shiloh we heard the guns on the first day. All extra baggage was thrown one side and we went forward in light marching order,” he recalled. “In the morning we were put on board the vessels and moved up toward Pittsburg Landing. We reached the field of battle on the 7th.” He continued, “That was the first experience the company had in battle and it suffered severely, twenty-three men being killed or wounded. I was struck twice, once in the hand and once in the leg.”

McGowan received a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant. More than a year later during the fighting at Chickamauga, he fell unconscious after a blow to his head. Captured, he spent the rest of the war in Southern prison camps. He mustered out of the army as a first lieutenant. Though he never regained his health, he lived well into his 90s, dying in 1936.

The Seventh Hour

Following the initial shock of the Confederate onslaught in the morning of the first day, Capt. James P. Millard and his comrades in the 18th Wisconsin Infantry gradually fell back with the rest of the main Union line. As the hours passed, the regiment fought in a desultory manner. During this period, parts of companies became separated and joined other regiments. About the seventh hour, the main portion of the regiment became nearly surrounded. To make matters worse, the Confederates caught them in a cross fire that killed the regiment’s colonel and major, and resulted in many other casualties. “In the confusion caused by this heavy loss, and before they could think of retreat, the enemy was among them, taking prisoners and firing almost in their faces,” according to the Military History of Wisconsin. Victorious Confederates nabbed Millard and hauled him off to prison. He eventually gained his release and ended the war as lieutenant colonel, but did not muster at that rank. He lived until 1892. His wife and a son outlived him.

Surrender

First Lt. William Gallagher and many comrades in the 14th Iowa Infantry were captured during the last stand in the Hornet’s Nest. One writer noted, “Their determined bravery to hold their ground cost them their own freedom however as they were finally surrounded, almost out of ammunition, in the late afternoon after holding out all day against repeated waves of attack. As the sun set they were forced to surrender and were taken off the field to prison camps in the deep south.”

After he gained his freedom, Gallagher returned to Iowa and married Mary Crawford. Soon after they wed, he returned to his regiment as a captain and served out the remainder of his 3-year enlistment. Gallagher died in 1872, his health compromised during the war. Mary, a son and daughter survived him. The boy, William Sherman Gallagher, was named for the Union general surprised by Confederate forces at Shiloh.

Special Thanks to Stan Hutson for his help in bringing this project together. Stan is employed with the National Park Service, currently at Stones River National Battlefield in the Facilities and Natural Resources department, formerly at Shiloh National Military Park. His interests include Alabama Confederate images and images related to the Battle of Shiloh and the Battle of Murfreesboro. An Afghanistan war veteran, he holds a Master’s degree in Public History from Middle Tennessee State University.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.