By Kurt Luther

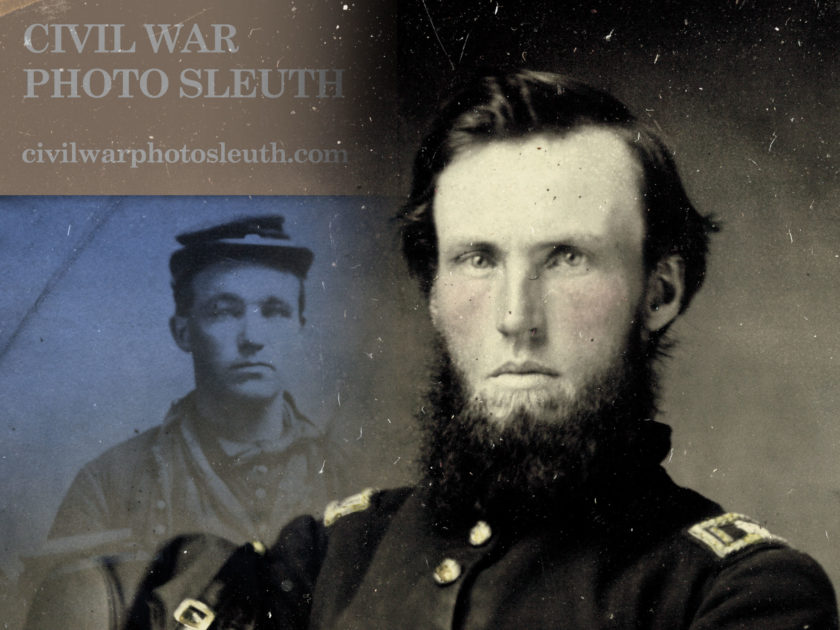

On Aug. 1, 2018, we celebrated the public launch of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that we hope will forever change the face of Civil War photo sleuthing. The mission of CWPS is to recover the names and stories behind every surviving Civil War-era portrait. It is an ambitious endeavor. But we believe that, with the passion and knowledge of the Civil War photography community, and armed with the latest technology, we can make it happen.

The website provides three main feature sets. First, it provides software tools for image analysis, including state-of-the-art face recognition technology and a powerful search engine. Second, it aims to be the world’s largest, most complete digital archive of identified and unidentified Civil War-era portraits. Currently, we have more than 15,000 identified photos, with hundreds more awaiting identifications. Finally, and most importantly, the site hosts an online community in which users can share information, debate possibilities, and help one another draw informed conclusions about Civil War images.

“The mission of CWPS is to recover the names and stories behind every surviving Civil War-era portrait.”

We hope these features will further provide CWPS users with a significant trio of benefits. To begin, you can easily search the database for Civil War portraits using a variety of search criteria: by name, rank, regiment, location or some combination of these. Next, and slightly more involved, you can add identified photos to our growing digital archive, either from your own collection or from a variety of suggested public resources. The third feature, which requires the most expertise, allows site users to identify unknown portraits through consideration of a mystery photo’s visual clues and provenance, as well as the appearance and military records of potential matches. Note that CWPS itself, on principle, does not make identifications. It’s simply a tool you can use, and the responsibility rests with the user.

Soft Launch: Gettysburg 2017 and 2018

We first announced CWPS in the Summer 2017 issue of MI. That June, we debuted a rough prototype at the annual Civil War Artifact and Collectibles Show in Gettysburg, Pa. Over the next year, we worked hard to respond to early feedback, improve the software’s capabilities, and make it publicly available via a free website.

A year later, in June 2018, we had a “soft launch” of an early version of the website, again at the Gettysburg show. Anyone who showed up to the MI table was invited to sign up for a free account and to bring unidentified photos to research on the site. We signed up dozens of beta testers, and, even in that short weekend, we identified several unknown photos.

These early successes suggested a couple of the likely benefits of the site. Collector Jim Brady stopped by the table with an unidentified carte de visite that included a Nashville back mark and a revenue stamp. The subject—a thin, mustached Union second lieutenant—stood with his unsheathed sword. CWPS revealed him to be Frank Richmond, a second lieutenant in Company D of the 152nd Illinois Infantry. The regiment spent a substantial portion of its one-year service in Nashville.

Another carte de visite, also depicting a Union second lieutenant, had already been tentatively identified as an officer of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry. However, Ken Fleming added it to CWPS, and the search results showed a much closer match: Lt. James C. Woodworth of Company H of the 25th Massachusetts Infantry. This second example suggests that the site may also invite new scrutiny of existing identifications.

Public Launch: Washington, D.C. 2018

Following the soft launch at Gettysburg, we worked closely with our beta testers to ready the site for a public, nation-wide launch on August 1. We selected the National Archives in Washington, D.C., as our debut location. While the building resides relatively close to many Civil War-related historic sites and accessible cultural institutions, the strongest draw resulted from an embrace of crowdsourcing and public engagement by David Ferriero, the current Archivist of the United States. Within the building, we held our event at the Innovation Hub, a new technology-enriched space where members of the public can scan and annotate historical documents. The Hub’s coordinator, Catherine Brandsen, told us that volunteer “citizen archivists” had already digitized more than 300,000 pages.

Launch day arrived, and the team was excited, but nervous. Would anyone show up, or want to create an account? Would the website crash? CWPS intern Natalie Robinson, a Public Relations and History double major at the University of Georgia, spent much of the summer planning the event, from publicity to catering. She also added more than 200 portraits of U.S. Colored Troops to the database. CWPS developer Vikram Mohanty, a Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech, and intern Ryan Russell, a Computer and Information Sciences major at Virginia Military Institute, had implemented scores of bug fixes and feature requests in the weeks leading up the launch.

Happily, our anxieties soon eased. Attendees filtered into the Hub even before the event officially started. David Ferriero greeted us warmly, and I sat down with him to give a quick demo. Other colleagues soon joined him, including Archives Specialist Jackie Budell, who manages digital partnership projects, such as the recent digitization of Civil War pension files and the photos they sometimes contain. Garry Adelman of the Civil War Trust and Center for Civil War Photography also arrived, and began testing the site with battlefield photos, while Civil War Times’ Melissa Winn, a photographer herself, documented the activities.

At 10 a.m. sharp, the countdown clock on the CWPS website reached zero. I typed a few commands on my laptop, and the site officially opened to the public. Around me, I heard the tapping of keys as people began creating accounts. A delegation from the Library of Congress began adding photos to the site, and prompted a sudden flurry of discussion among them. Karen Chittenden, Senior Cataloging Specialist for the Prints & Photographs Division, had found a remarkable Ohio infantryman similar to the tintype she had uploaded. Leery of confirmation bias, Chittenden resisted the urge to make the identification until she could perform further research. Her diligence was rewarded upon later discovery that the unidentified soldier in the tintype had sergeant’s chevrons hidden behind the mat preserver, while the potential match never rose above the rank of private. Her experience provided a timely reminder of the ease of finding similar-looking soldiers and the necessity of careful research.

At noon, MI Editor and Publisher Ron Coddington and I made introductory remarks to the assembled group, as well as online viewers via a Military Images Live video broadcast on Facebook. I suggested that although the technology has improved, Civil War photo sleuthing is as old as the Civil War itself. From the nationwide search for the children in Sgt. Amos Humiston’s ambrotype to the portraits tacked to the walls of the Dead Letter Office (see the Spring 2016 issue of MI), to our CWPS website, the common and critical ingredient lies in a community of people willing to contribute their time and knowledge. To showcase the potential of CWPS, I identified an unknown assistant surgeon in a Library of Congress tintype as Francis M. Eveleth of the 7th Maine Infantry and the 1st Maine Veteran Volunteers. Tom Liljenquist, who had donated the tintype, was present to receive the identification.

In his remarks, Ron Coddington discussed the larger historical context for our project. He traced the audience for Civil War portraits as increasingly public, from private family albums and home displays in the immediate postwar years, to regimental history books and veterans’ society collections around the turn of the 20th century, to collectors and researchers in the mid-20th century to the present day. With CWPS, he suggested, we can broaden the audience of Civil War photography still further, and “make it accessible beyond the thousands and into the millions of the individuals who think about these images, and families who want to connect with ancestors.”

Beyond our local event, we were thrilled to see photo sleuths around the country signing up for the site and adding photos, bolstered by generous publicity from the Civil War Trust, the Center for Civil War Photography, the Nau Center for Civil War History at University of Virginia and the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech, among others. In Doug York’s Civil War Faces group on Facebook, members posted CWPS screenshots, and sought opinions on potential matches. The query provoked lively and diverse responses. Dave Morin, a noted collector of New Hampshire images, successfully identified two unknown soldiers within hours.Next Steps

From its inception, CWPS is of the people, by the people, for the people. I intend to keep the core features and benefits described here completely free, and to encourage the flow of information and minimize barriers to contributing images. (Our operations are currently funded by grants, as well as private donations.) We hope, if you haven’t already, that you will visit Civil War Photo Sleuth and join our photo sleuthing community.

We also welcome your feedback on the site, either via email or by submitting the feedback form on CWPS. We will continue to make regular updates and improvements, announced through our Facebook page and elsewhere.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.

© Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.