By Dr. Anthony Hodges

As the initial rays of sunlight on the morning of Nov. 25, 1863, broke over the mountains east of Chattanooga, nearly everyone around the Tennessee city, whether a Confederate huddled in the trenches atop Missionary Ridge or a federal in the besieged city, strained their eyes looking south towards the fog shrouded peak of Lookout Mountain.

The Union Army of the Cumberland, defeated along Chickamauga Creek two months prior, had been trapped in Chattanooga ever since. During the days and weeks that followed, the men had been reduced to quarter rations. And many faced starvation.

Then, in late October, supplies flowed into the beleaguered city after the aptly named “cracker line” had been opened with the capture of Brown’s Ferry on the Tennessee River.

Reinforcements followed. Chief among them was a force led by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who relieved army commander Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans. From the east came two full corps—the 11th and 12th—from the Army of the Potomac under the command of Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker. From the west came Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and his troops, who had recently reduced the Mississippi fortress city of Vicksburg.

Though the siege of Chattanooga was broken, Gen. Braxton Bragg and his Confederate Army of Tennessee remained in key elevations surrounding the city. Grant set his sights on driving Bragg’s troops away. To do it, he planned a diversionary attack on Bragg’s left, positioned on picturesque Lookout Mountain. He entrusted Sherman with the main attack against Bragg’s right atop the Tunnel Hill section of Missionary Ridge.

On Nov. 24, three of Hooker’s divisions assaulted Lookout Mountain. Low hanging clouds that enveloped the mountain obscured much of the fighting. Musketry and cannon flashes discharged faintly in the fog. Though the heavy firing died down around 9 p.m., desultory musket fire continued well past midnight. It appeared to be a federal victory, based on the movement of the faintly visible barrel flashes of musket and cannon, but no one was sure given the weather.

The next morning, the warm sunshine burned off the mist and the victor of the previous day’s combat gradually came into focus, dimly at first, and then more clearly as the sun’s rays overcame the fog. Movement from atop the mountain was visible. As the view sharpened, a group of men could be seen. When the final mist dissipated, the Stars and Stripes stood out from atop the former Confederate stronghold.

The banner was the national colors of the 8th Kentucky Infantry floating above the “Point,” an exposed rock ledge that anchored the northern terminus of 83-mile long Lookout Mountain. A newspaperman present remembered the elation of the federal forces when they glimpsed the waving regimental flag: “The right of the Federal front, lying far beneath, caught a glimpse of its flutter, and a cheer rose to the top of the mountain, and ran from regiment to regiment, through whole brigades and broad divisions, till the boys way around in the face of Mission Ridge passed it along the line of battle.” The accompanying cheers of the Union soldiers left no doubt of the outcome of Lookout’s fog shrouded struggle.

The officer who commanded the flag raising party, Capt. John Wilson, recalled that just before daylight, Brig. Gen. Walter C. Whitaker approached Col. Sidney Barnes of the 8th with a request. “‘Colonel Barnes, have you an officer that will volunteer to carry your flag and place it on top of the mountain.’ I said, ‘General, I will go.’ Turning to the regiment, he said, ‘How many of you will go with Captain Wilson. I could order you up there, but will not, for it is a hazardous undertaking; but for the flag that gets there first it will be an honor.’ Five men went with me. I handed my sword to my Color-Sergeant to bring up, and I took the flag and started.”

Wilson continued, “Those who have seen the awe-inspiring precipice at the top of the great mountain can realize what a serious undertaking was before us, not to mention our lack of knowledge concerning the Confederates, who the day before had held Hooker at bay. Dim daylight was dawning. We crept cautiously upward, clutching at rocks and bushes, supporting each other, using sticks and poles and other such aids as we can gather. At every step we expected to be greeted with deadly missiles of some sort from the enemy. But fortune favored us, and before sunup, I, in front, reached the summit and planted the flag on top of Lookout Mountain. It was the highest flag planted during the war.

Wilson added, with relish, “We were the lions of the day in the Union army.”

Wilson added, with relish, “We were the lions of the day in the Union army.”

After the war, several regiments claimed the honor of being first to fly their flag upon Lookout, but no doubt exists that Wilson and his Kentuckians arrived first. Their closest competitor was the 96th Illinois Infantry, according to one of its veterans. He explained that the “showy stand of colors” carried by the 8th outshone their flag, which “was hardly more than a pole, the staff being splintered by Chickamauga bullets and the silk torn from it by the handfuls by the storm [of lead].”

Wilson and his five companions were granted a 30-day furlough by Maj. Gen. George Thomas in recognition of their heroic conduct.

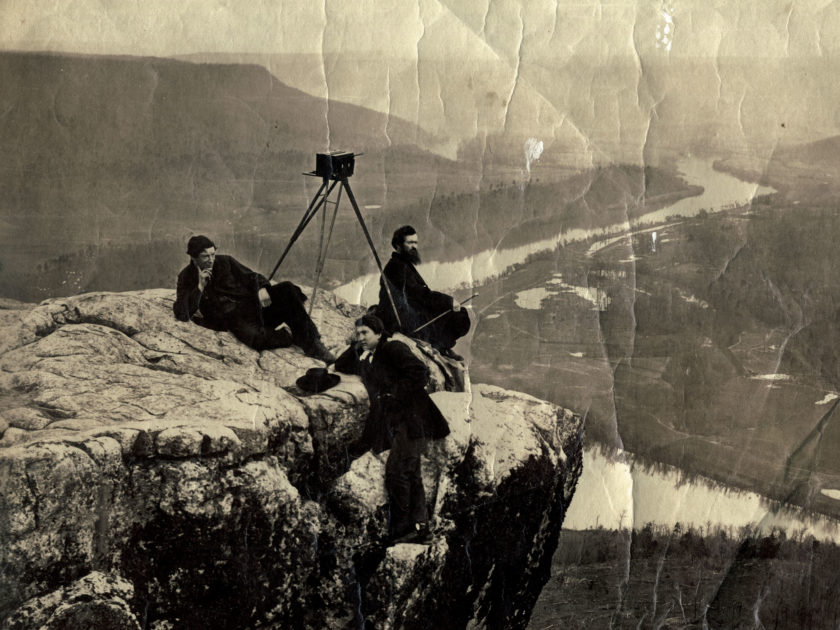

Before they left on their well-deserved break, Robert M. Linn of Marion, Ohio, who had been a civilian mapmaker and photographer with the Union army, approached Wilson and the scaling party. Captivated by Lookout Mountain, Linn had leased the mountain’s northern terminus from the James A. Whiteside family shortly after the fighting ended. Linn established a photograph business, which he christened his new studio Gallery Point Lookout.

Linn invited Wilson and his companions to re-enact the historic raising of the first flag atop Lookout—one of the earliest Civil War re-enactments photographed. They agreed, and posed upon the scaling ladders they used to ascend Point Lookout. Wilson, perched atop the ladder, waved his hat and faced the camera as his comrades followed. They next posed, Wilson in the lead with the flag, atop Point Lookout. His companions with their muskets joined him at the ready, should any rebels dare show themselves.

History does not record if Wilson and his men received any compensation. If they had, they might have been wealthy men given that a comparison of surviving copies of the image indicates it was printed and sold well into the 20th century.

Linn soon had a burgeoning business and invited his brother, “J.B.,” to join him. James Birney Linn, who had served with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, accepted and went to work alongside his brother.

Among the natural features that inspired the Linns were the “Rock Cities” of Lookout. These sandstone boulders, uniquely carved by the erosive power of the wind, rose higher than two story buildings. Visitors accessed them through ancient paths. The explorers included Confederate nurse Kate Cumming, who remembered them as “a natural curiosity…trees, castles, and mountains of solid rock, cut by nature’s masonry.”

Also of interest to the Linns was a picturesque lake and falls formed by Rock Creek as it flows down Lookout’s eastern brow, with an assist from natural damming. Known as Lake Seclusion, the name changed before the war to Telulah Lake, probably to increase tourism. Legend had it that a beautiful Cherokee princess named Telulah had committed suicide by throwing herself in the falls, rather than enter into an arranged marriage. Soldier visitors further altered the name by whittling Telulah Lake into “Lula,” a moniker that persists to this day.

The Linns also trained their lens on Lookout Mountain Hotel, or Summertown. Built in 1857 by Whiteside as a refuge from summer heat, the hotel consisted of a large white columned main building and 25 cottages. The hotel saw some service as a hospital when the Southerners held Chattanooga, but it was abandoned when the entertainment-starved patients rolled rocks down the mountain onto unsuspecting travelers. It also served as a Union hospital and administrative complex after the fighting concluded.

Portraits of soldiers and civilians at the Point however, were the bread and butter of the business. Among the Linn’s first individual portraits was that of George D. Foster, known as the “Old Man of the Mountain.” The son of a combat-wounded Revolutionary War veteran and a staunch Unionist, he had lived on Lookout for a quarter century. Foster helped build the Lookout Mountain Hotel and ran the tollgate for the Whiteside Turnpike that ascended the mountain. He became a popular figure after the fighting due to his Union sentiments and colorful personality. Many of the soldiers who came to Lookout to get their portraits taken called on him, including William T. Sherman and Joseph Hooker, both of whom he credited with giving him his nickname.

This is the first in a three-part series. In our second installment, we look at Linn’s “Portraits on the Point,” a selection of representative soldier photographs taken singly and in groups at Gallery Point Lookout during the war. In our third and final installment, we will explore Lookout Mountain photography during the formation of Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park and the veterans’ reunions.

Special thanks to the late Scott Sanders for his dedication in collecting Lookout Mountain photography and to Vann Martin of the Veteran’s Attic for help returning many of these images to the Chattanooga area.

References: Taylor, Pictures of Life in Camp and Field, Baumgartner and Strayer, Echoes of Battle: The Struggle for Chattanooga, Walker, Lookout, The Story of a Mountain, Cumming, A Journal of Hospital Life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee, Free Press (Chattanooga), Aug. 31, 1997, Hoobler, Cities Under the Gun, Schroeder-Lein, Confederate Hospitals on the Move.

Dr. Anthony Hodges, a retired dentist, has been a lifelong collector of memorabilia related to Chickamauga and Chattanooga and has served the National Military Park for more than 40 years as a living history volunteer or “Friends” board member.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “The Linns of Lookout: The enterprising brothers behind a legendary photograph gallery”

Comments are closed.