By Ronald S. Coddington

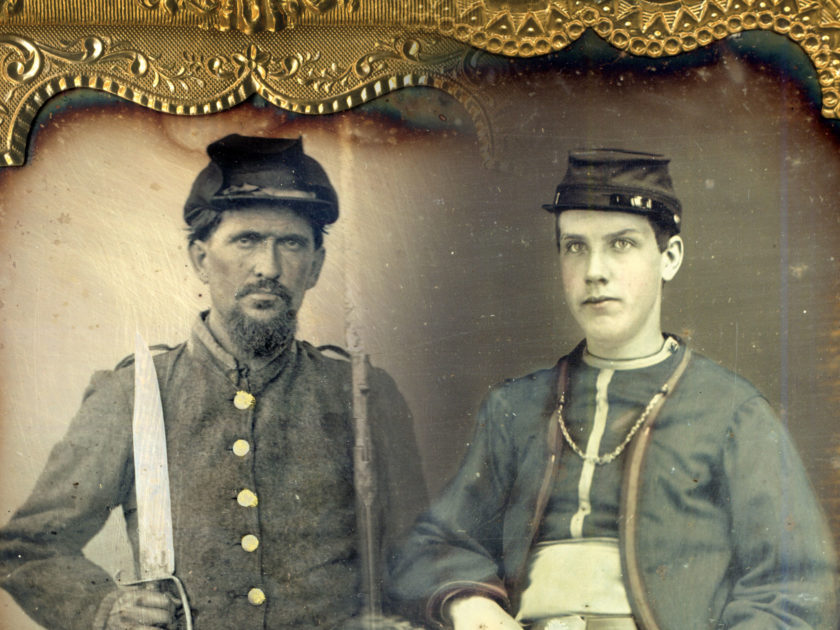

This portrait of a Confederate soldier sits squarely between two unique periods in history. On one side, his likeness recalls the whirlwind of patriotic fervor following Fort Sumter as loyal Southrons enlisted in the nascent Confederate army. On the other, this photograph is a rare example of the daguerreian arts during the tail end of the distinctive format’s reign.

The daguerreotype had come into existence more than two decades earlier. In January 1839, Frenchman Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre announced the first successful commercial photographic process. News traveled quickly to America, where the daguerreotype was hailed as a beautiful invention, of Rembrandt perfected. Entrepreneurs in New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Cincinnati, St. Louis, New Orleans and elsewhere quickly mastered the medium. These pioneers and those who followed them spread photography to the far corners of antebellum America. Some, notably Mathew B. Brady, rose to fame and prosperity as photographer to the power elite.

The daguerreotype remained the unchallenged leader in American photography for nearly 15 years. Then in the mid-1850s, the introduction of cheaper formats eroded the dominant market position of the daguerreotype. The ambrotype used less expensive glass in place of the silver and copper plate of the daguerreotype. The melainotype, also known as the ferrotype and after the war as the tintype, utilized an iron plate. Another French format, the carte de visite or card photograph, arrived in the U.S. in 1860. It further contributed to the daguerreotype’s gradual demise.

Of the four major formats—daguerreotype, ambrotype, tintype and carte de visite—the ambrotype dominated the market during the war’s first year, according to an analysis of 6,193 advertisements and other references in 1861 on Newspapers.com.

Ambrotypes made up about half the total citations in 1861. Daguerreotypes were cited second most often at 35 percent. But these references were overwhelmingly ads placed by ambrotypists seeking to copy old daguerreotypes. In one Ohio newspaper, the Cadiz Sentinel, the proprietor of Davis’ Sky Light Ambrotype Gallery falsely claimed that most daguerreotypes will fade and “should without delay be copied into the imperishable Ambrotype, which will improve them fifty percent.” Copying images was new business, one that would become a reliable portion of photographer’s earnings for decades to come.

Ambrotypes made up about half the total citations in 1861. Daguerreotypes were cited second most often at 35 percent. But these references were overwhelmingly ads placed by ambrotypists seeking to copy old daguerreotypes. In one Ohio newspaper, the Cadiz Sentinel, the proprietor of Davis’ Sky Light Ambrotype Gallery falsely claimed that most daguerreotypes will fade and “should without delay be copied into the imperishable Ambrotype, which will improve them fifty percent.” Copying images was new business, one that would become a reliable portion of photographer’s earnings for decades to come.

Tintypes composed about 11 percent of the total citations. Why so few mentions were made despite the large numbers that survive is a mystery.

Only 6 percent were cartes de visite. By the end of the war, the carte climbed to the top spot with 56 percent of total citations for all of 1865. (For more information, see Military Anthropologist on page 4.)

Though there can be no doubt that the daguerreotype had passed its prime, some photographers continued to work in the medium.

A close study of Newspapers.com ads in April 1861 found two galleries actively promoting the making of new daguerreotypes. They were Southern—Alexandria, Va., and Nashville, Tenn. In both instances, the photographers also promoted contemporary formats.

There were other daguerreotypists in practice during this time who either did not advertise the fact or advertised in publications not represented on Newspapers.com. Case in point is the Union daguerreotype pictured here: A Northern soldier dressed in the first uniform of the 9th New York Infantry.

In context, these daguerreotypes rate among the rarest wartime images. Theories abound as to why soldiers’ likenesses were captured in the fading format rather than by the more fashionable ambrotype, tintype or carte de visite. A surplus of daguerreotypist’s supplies may have extended its life. Some may have preferred the superior qualities of the daguerreotype, despite the higher costs versus the new formats. Other photographers may have been slow to adapt to new methods.

Whatever the reasons, two items are noteworthy: These images represent the enduring legacy and beauty of the daguerreotype, and its gradual exit from the national stage.

Special thanks to Dan Binder, Mike Medhurst, Dan Miller and Erin Waters.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor & Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.