By William T. Campbell, Ed.D, RN

A range of medical staff and support workers performed a critical function on both sides of the American Civil War, servicing general hospitals and saving countless lives along the way.

Surgeons, assistant surgeons and/or acting (contract) surgeons occupied leadership positions. They were assisted by nurses, including many convalescent or invalid soldiers detailed from their regiments, and women who volunteered from civic life and religious orders or were recruited by Dorothea L. Dix and paid by the government. Medical attendants, ward masters, cooks, laundresses, and guards rounded out the group.

The final and often most valuable member of the medical staff was the hospital steward. These individuals were essentially pharmacists, a title the army adopted 40 years after the war.

Chronically undermanned and always overworked, regulations called for one steward per general hospital. A second man was assigned if there were more than 150 beds and a third if the hospital numbered 400 or more beds. They were also assigned to regiments in the field and ships at sea.

Qualified stewards did not come easy. Candidates were often found among the ranks of druggists who labored in civilian apothecary shops. They compounded prescriptions and even made drugs from raw materials using the iconic mortar and pestle. They were chemists rather than those who simply filled prescriptions from larger bottles of manufactured pills.

These men were in great demand in military and in civilian life. Case in point: the commonwealth of Virginia petitioned the Confederate Congress to not allow civilian druggists or chemists to volunteer or be drafted as they were needed in the community. There were only 45 pharmacists in the entire commonwealth, which had a population of 1.6 million white inhabitants and about a half million slaves according to the 1860 census. After the war began and the Union blockade went into effect, Virginia’s pharmacists were called upon to manufacture medicines.

The first authority and primary reference on hospital stewards was published in 1863 as The Hospital Steward’s Manual: For the Instruction of Hospital Stewards, Ward Masters, and Attendants in their Several Duties. Author Joseph J. Woodward, an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army, wrote it following a suggestion by the army’s Surgeon General, William A. Hammond.

Woodward laid out a set of broad medical qualifications of applicants, which went far beyond the scope of the pharmacist. They “must have…sufficient knowledge of…pharmacy to take charge of the dispensary, acquainted with minor surgery, …application of bandages and dressings, extraction of teeth, application of cups and leeches, …knowledge of cooking.”

Despite the small pool of candidates, the army conducted a rigorous selection process to fill positions that began with an official application. In contrast male nurses were usually temporarily detailed without change in rank or title from inexperienced enlisted men.

One of the men who applied to be a hospital steward, Charles F. Beal, served as an acting assistant steward at Dumbarton Street Hospital in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. Beal explained to his father in a letter dated Jan. 1, 1863, that he had resigned his assistant’s position and applied for a hospital stewardship in the regular army. He said the position was very difficult to obtain and he had gathered recommendations from three surgeons in preparation for his application.

Woodward’s Manual suggested that candidates be “18-35 years old, able-bodied, free of disease, honest and upright,” of “good intelligence, having a knowledge of English, able to spell and write correctly,” and “industrious, patient, and good tempered.” There was a competitive exam to be taken. Stewards were screened for previous medicinal experience. A history of having worked as a druggist, chemist, or apothecary clerk in civilian life added a huge plus.

Previous experience even as a medical student was greatly beneficial. After the exam, interviews, and a review of references, the Secretary of War had to approve the appointment. With the process successfully completed, the hospital steward became a non-commissioned officer. Woodward explained that the position was equal to an ordnance sergeant and next in rank after first sergeant. The appointment was permanent for the duration of the war and the steward could not be returned to regular duty—they were part of the Medical Department or Hospital Department. This certainly benefitted the hospital’s medical staff, as the men who gained experience would be retained, unlike male nurses.

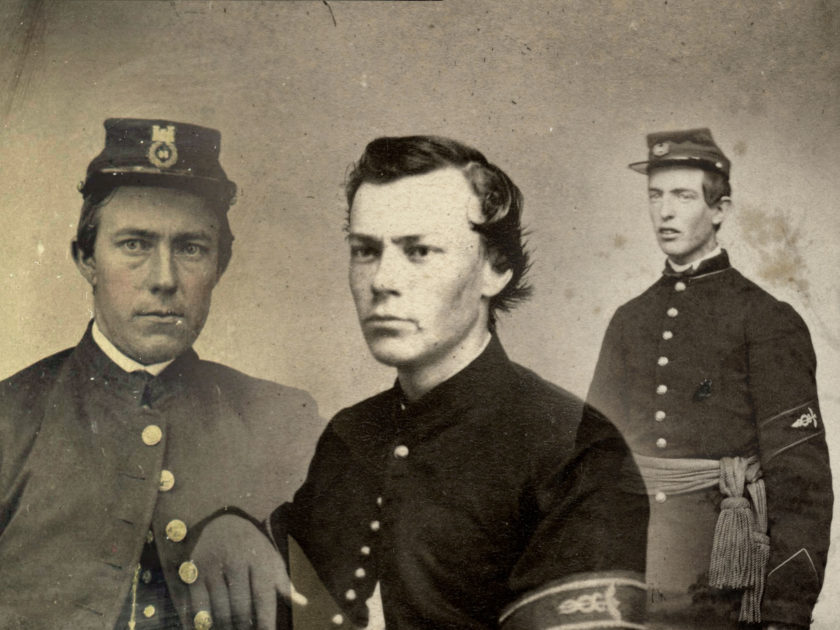

Woodward’s Manual also described the uniform and symbols of the position and rank. The insignia, color code, and uniform were distinctive and certainly distinguished this position, then and in images viewed today, from the rest of the medical staff:

1. The distinctive cloth insignia was the half chevron of caduceus and snakes worn on the upper sleeves, not to be confused with the nurse which according to Woodward was to wear the same chevron on the lower left sleeve.

2. The dress or ceremonial sword was the non-commissioned officer’s sword, not the medical staff sword carried by surgeons.

3. The dress sash was to be of red worsted wool, not the red or crimson silk sash of the artillery branch and not the green silk sash of the surgeons.

4. Dress hats could be adorned with a feather or plume, an eagle pin on the right side, a gold laurel wreath on the front with a silver US, and a green and buff hat cord. The pin was to be US, not MS, which was reserved for medical staff use only.

5. The undress uniform, for fatigue purposes or hospital work, included the blouse or sack coat with the same half chevron on the upper sleeves. The pants were sky blue enlisted infantry trousers with a one-and-a-half inch wide crimson stripe down the outer seams. The red/crimson stripe (and wool sash) signaled the wearer was a non-commissioned officer, not a member of the artillery branch. A three-quarter inch wide crimson stripe would also designate a non-commissioned officer, but represented a corporal. A hospital steward would never hold this rank.

6. The undress cap was the enlisted man’s regulation forage cap.

The roles and responsibilities of the hospital steward varied depending on his duty location. In the hospital and acting as the pharmacist, he compounded (measured, weighed, mixed, rolled, cut, polished) prescriptions as written in the prescription book by the surgeons, rather than just filling them from a bulk supply. He also verified that the medication was actually administered although he was usually not the person who gave it. A nurse usually performed that duty, although Mary Gillett in The Army Medical Department 1818-1865 observed “…the Hospital Steward who before the war often added the role of nurse to his other duties…”

As hospital administrator, the hospital steward was responsible for inventory and ordering of medical supplies, hospital supplies, record keeping, and overall hospital administration. His inventory of records was never ending. It included the Steward’s Weekly Report, an enormous spread sheet. The number of beds, linen, clothes, dishes, and even spittoons, were counted and recorded on a weekly basis. In the field and on the march, the dispensary had to stay mobile, and required quick assembly and disassembly. Much of his time was spent in packing precious glass bottles of medications. Dr. Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, even specified that the hospital steward should carry the hospital knapsack for the surgeon when on the march.

The Manual also contained chapters that discussed hospital attendants and nurses. Woodward explained that the hospital steward supervised male nurses but not the female nurses. He stated: “Enlisted men are under the orders of the surgeon…look up to [him] as their commanding officer… [and] are also under the orders of the hospital steward, to all whose lawful commands they must yield prompt obedience.” The supervisory role similarly echoed in the South, where the regulations for the Confederate Medical Department noted that “the cooks and nurses are under the orders of the stewards.” While the term nurse did not specifically pertain to males or females, one must remember that the South was slow to accept female nurses during the war. In contrast, regarding the female nurses, Woodward added, “she should heartily co-operate with the steward, and strictly obey the orders of the medical officers.” It would appear from this wording that while all Union female nurses were under the orders of the surgeon (and for some also the supervision of Dix) they did not necessarily answer to the hospital steward. His leadership and supervision were reserved for the male nurses.

Nevertheless, the hospital steward proved an invaluable asset to the hospital staff with his many varied roles and responsibilities.

References: Campbell, W. T. “The Hospital Steward: His Role & Responsibilities Including His Relationship to Nursing,” Surgeon’s Call: Journal of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine; Gillett, The Army Medical Department 1818-1865; Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac; Moore, Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States; Woodward, The Hospital Steward’s Manual: For the Instruction of Hospital Stewards, Ward Masters, and Attendants in their Several Duties.

Dr. William T. Campbell is Professor of Nursing at Salisbury University in Maryland. He has been a student of the Civil War for over 50 years. The historical spark was ignited as a youth growing up in southern Delaware when his aunt would frequently take him to visit Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania battlefields and Fort Delaware. With his later profession as a registered nurse this interest evolved into the study of medicine, pharmacy, and nursing during the 1860’s. A member of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, he has served as a docent in uniform as a Union hospital steward at the Pry House Field Hospital Museum on the grounds of Antietam Battlefield National Park in Sharpsburg, Md.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.