By Daniel R. Glenn

A loud knock jolted Henry McCarthy from sleep at his home in a black community in New Bern, N.C., on the night of April 20, 1864. He made his way to the door and opened it. Four white federals stared back at him. They first asked him for liquor, and then, if there was “any woman there who would screw.”

Stepping outside, McCarthy replied nervously, “there was only one, and she was in old man Winn’s house and that if they went there the old man would kill them.” One of the soldiers grabbed McCarthy by the neck, pushed him back, and ordered him to return to bed.

McCarthy hurried inside, watched the group continue down the path from a window, and then lay down. About five minutes later, just as he dozed off, another noise—this time the crack of a gunshot—shattered the nighttime stillness.

At a nearby house slept old man Lot Winn. He did not hear the shot, but awoke to a desperate voice calling for him. Darting from his bed and stepping outside, Winn saw Edmund Smith, a neighbor, coming towards him, and screaming for help. Just as Smith reached the house, Winn glimpsed a shadowy figure 40 yards away raise a gun to his shoulder.

Moments later, a report echoed through the woods. Smith collapsed in his tracks with a bullet in his head, just a few feet short of safety.

Someone called for an ambulance, which rushed Smith to a nearby army hospital. The physician who treated him, John Gore Johnson, had only recently joined the army.

Johnson, 39, had come to medicine later than most. Back in his hometown of Worcester, Mass., he started his adult life as a cobbler in the family business. But his frail health could not endure the rigors of factory work, and he turned to teaching. He was good at it, and might have remained an educator for the rest of his days.

In 1847, however, after tuberculosis claimed a younger brother and sister, Johnson, then 22, heard the call to medicine. According to a biographer, “He purchased books, as he had the means, and studied privately until able to attend the medical college.”

Johnson graduated from Worcester Medical College in 1856, and settled into a successful practice. Soon, he and his wife, Sally, started a family that grew to include six children.

In November 1863, Dr. Johnson answered a new call—from the federal government. He entered service as an acting assistant surgeon, a contract position that entitled him to wear an officer’s uniform. He reported to New Bern, N.C., for duty.

In this capacity, he attended to the critically injured Edmund Smith on the fateful night. His head wound proved mortal, and Smith succumbed the following day around 3 p.m.

Meanwhile, the provost and other military authorities launched an investigation into Smith’s death. What they found related to the shooting of an unarmed black man was disturbing.

On June 10, Judge Advocate Edwin S. Jenney, major of the 3rd New York Light Artillery, convened a court-martial in New Bern. The tribunal tried Sgt. Arthur J. Woods of the 12th New York Cavalry for the murder of Edmund Smith. Woods, about 21 years old, had been arrested four days after the death of Smith, and confined until the trial date.

At the trial, Surgeon Johnson delivered barebones testimony regarding his care of Smith. The recollections of McCarthy and Winn though, proved much more relevant.

The court also heard from two soldiers present that night. Pvt. David McDonald of the 3rd New York Artillery and Cpl. Harmonious Bridges of the 12th painted Smith’s murder as accidental. In separate testimony, McDonald and Bridges admitted that they and two others, Sgt. Woods and a sailor named Durfee, had gone to Smith’s house hoping to find “a woman of bad character” and that they might “go down and get something.” But the two also claimed that they had waited at a distance as Sgt. Woods and Durfee knocked on Smith’s door.

Less than a minute later, Bridges stated, he heard a gun discharge. “Somebody has fired,” McDonald exclaimed, and the two sprinted toward the sound. McDonald testified that he and Bridges approached Smith’s house to find Durfee holding Smith down while Woods demanded to know the whereabouts of the gun, and why he had fired it. Smith insisted that he had no such weapon. “That is a damn lie,” Durfee roared, “you tell me where that gun is, or you will fare worse.”

McDonald testified that Durfee reached behind Smith’s bed and found a double-barreled shotgun. Seeing the weapon, Smith shouted, “It ain’t loaded, it is not loaded.” Durfee then pushed him out the door, where he stood, six or seven feet away. Woods turned to Durfee and remarked “let me have the gun, and I will see whether it is loaded or not.” Snatching the shotgun, he “snapped the right cap” but with no effect. Then, raising the weapon to a “charge” position, he tried the other cap, and the gun went off. Smith “jumped into the air and fell flat on the ground.”

Bridges added that Woods then threw the gun down, saying, “I do not see how that was,” and left the scene.

In his defense, Woods claimed that he merely tried to “ascertain whether the gun was loaded … [and] had the misfortune to discharge it.” He attributed the killing to “nothing more than carelessness in relation to the unfortunate occurrence.”

Certain facts of the case are indisputable. Clearly, the soldiers had gone looking for an amorous woman, that Smith fired an initial shot from inside the house, and that Woods fired the second, fatal round.

“You as Father Abraham will be as lenient as possible with me on this my first and only misfortune.”

The soldiers’ testimony is inconsistent, however, with that of Smith’s neighbors. The discrepancy hinges on the location of Smith at the time of the second shot, and the extent to which Woods intended to shoot him. The soldiers’ accounts suggest that Smith was shot just outside of his own house, whereas Lot Winn’s testimony indicates that Smith had run some 40 yards to Winn’s house before Woods raised the weapon to his shoulder, aimed and discharged the lethal round. If true, then Woods took careful aim and intentionally shot Smith in cold blood as he tried to escape. If the soldiers were telling the truth, then Woods, though he pointed the gun at Smith, did so in the flustered aftermath of Smith firing the same gun supposedly in his direction, and thus, was not so deliberate as Smith’s neighbors suggest.

The court-martial convicted Woods of a lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced him to a year of hard labor and forfeited pay.

Following the verdict, Brig. Gen. William J. Palmer reviewed the case and approved––albeit reluctantly––the proceedings and findings. “This looks very much like a case of deliberate murder,” he remarked. “The sentence of the Court seems to be altogether insufficient.”

Despite his comparatively light sentence, Woods appealed to President Abraham Lincoln for clemency. In his petition, he sought to discredit the testimony of the black witnesses, and hoped that “you as Father Abraham will be as lenient as possible with me on this my first and only misfortune.” Woods also included supporting statements attesting to his previous good behavior from two commanding officers and a childhood friend.

Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt reviewed the case and questioned whether the sentence was “too severe a penalty, for a reckless misdemeanor.” He added that while the incident resulted in a homicide, it was “committed by a man whose general character appears to have been excellent.”

Lincoln stayed true to his reputation as “The Soldier’s Friend” for reducing or commuting sentences. In mid-August, the commander-in-chief downgraded Wood’s punishment to imprisonment and loss of pay only through Oct. 20, 1864.

Woods served out his abbreviated sentence, and settled in Chicago after the war. He joined the Grand Army of the Republic and died at about age 47 in 1890.

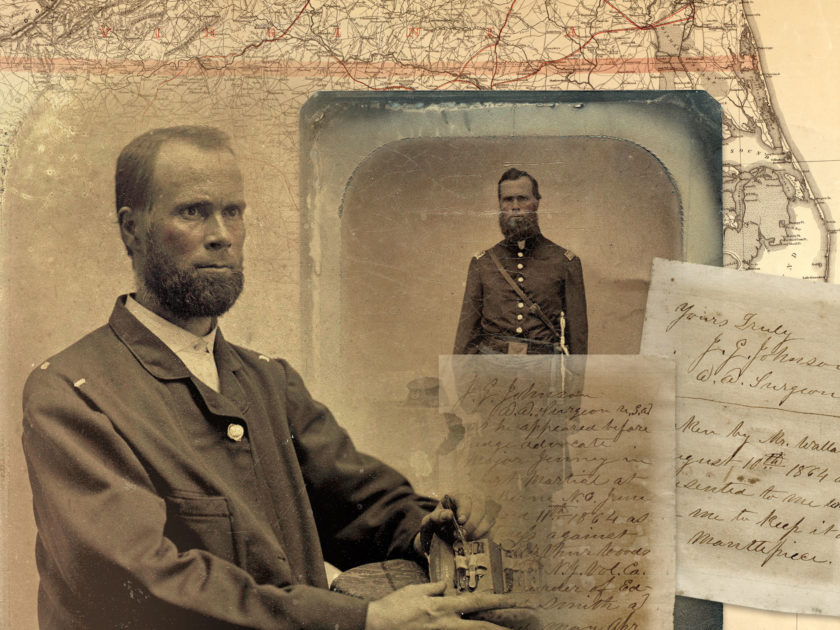

The perfunctory testimony by Johnson amounted to a minor point in an otherwise sordid trial. Still, the events stayed with him, as evidenced by the note enclosed with this tintype portrait. Johnson resigned his position due to feeble health a month after sitting for the photograph. He returned to his family in Massachusetts and resumed his practice.

Johnson died in 1896 from tuberculosis, the same disease that killed his siblings a half-century earlier, and had inspired him to become a physician. He was 70.

References: Court-Martial Case File LL-2255, National Archives; Arthur Woods pension and military service records, National Archives; Transactions of the National Eclectic Medical Association, Vol. 24 (1897).

Daniel R. Glenn is a student at Christopher Newport University majoring in American Studies and political science. He plans to attend law school.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.