By Tom Huntington

Maine veterans returned to Pennsylvania in October 1889, 26 years after they had fought at Gettysburg with the Army of the Potomac. For three days in July 1863, the Union troops had withstood the attacks of the Army of Northern Virginia, and they had emerged victorious in what would be the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. When the smoke had cleared, nearly 8,000 soldiers were dead, 27,000 were wounded, and an additional 11,000 were captured or missing. The soldiers who had fought then were now much older, if not always wiser. It was likely that many of them were making their first trip back to the field where they had risked life and limb for the Union cause on a battlefield far from their homes. Unlike so many, they had survived that battle and the war, and now they returned to reminisce, exaggerate and relive one of the crowning moments of their lives.

The chief reason for this visit was the dedication of monuments to the Maine units that had fought here. The solid stone sentinels, many of them chiseled from Hallowell granite, were intended “to commemorate and perpetuate the conspicuous valor and heroism of Maine soldiers on that decisive battlefield of the war of the rebellion.” There were 15 monuments, representing the regiments, batteries, and battalions that had struggled in the epic battle.

Dedication day, October 3, brought perfect autumn weather. The ceremonies began at 9 a.m., with a national salute fired from guns on Cemetery Hill, the strategic high ground that Maine native Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard had selected as an ideal defensive position when he arrived there on the first day of battle. After the salute, Gov. Edwin C. Burleigh and the state’s other Gettysburg commissioners set out to inspect the monuments; accompanying them was Hannibal Hamlin, the Maine Republican who had served as President Abraham Lincoln’s first vice president. That evening a large crowd gathered at the county courthouse for the overall dedicatory ceremonies. Anyone eager to hear the former vice president speak would have been disappointed, because Hamlin’s exertions during the day had left the 80-year-old too exhausted to attend. Maj. Greenlief T. Stevens, who had commanded the 5th Maine Battery during the battle—and had the knoll where his battery was posted named after him—called the meeting to order and introduced a speaker who still retained enough energy to talk.

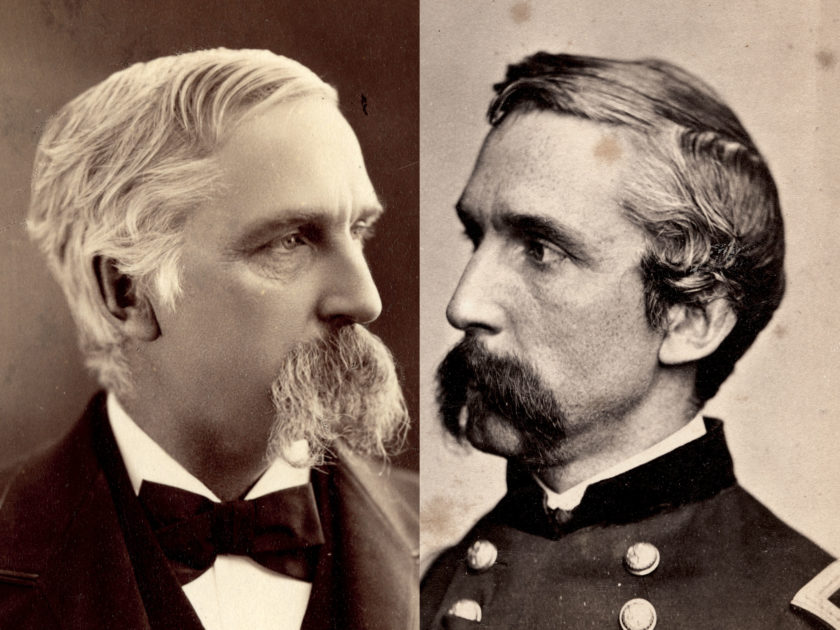

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain stood to speak. Twenty-six years earlier he had commanded the 20th Maine Infantry on the rocky, wooded slopes of Little Round Top, where his soldiers had successfully fought off attack after attack by Confederates from the 15th Alabama Infantry. Later in the war, Chamberlain was severely wounded, shot through both hips during a battle outside Petersburg, Va. Chamberlain’s wounds were so severe, in fact, that Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant promoted him to brigadier general on the spot, thinking that he wouldn’t survive. Perhaps they had been mortal wounds—but if so, they wouldn’t kill Chamberlain until more than five decades had passed. In the years after the war, Chamberlain served as governor of Maine and president of his alma mater, Bowdoin College. His Civil War experiences, especially his successful defense of Little Round Top, remained the high point of his life.

Chamberlain was now 61 years old. His hair and drooping mustache had long since turned gray, and his war wounds left him in near-constant discomfort. If anyone had a right to be tired, it was Chamberlain. He had already given a speech that day, when he and other veterans of the 20th Maine had assembled with their wives and others at Little Round Top to dedicate their monument.

“You were making history,” he told the men who had fought under him. “The centuries to come will share and recognize the victory won here, with growing gratitude. The country has acknowledged your service. Your State is proud of it.” After the ceremonies on Little Round Top, the gathering moved west through the woods to pay homage at the spot where the regiment’s Company B had been during the fighting, when it had risen up from behind a stone wall at the struggle’s climax to pour a volley into the unsuspecting Confederates’ flank. Then the group climbed the steep slopes of Big Round Top to dedicate the monument that marked the position the regiment had taken and occupied during the night of July 2. Chamberlain made another short speech there.

Now he had one more speech to make. As he looked out over the faces in the audience, Chamberlain could be excused if he saw ghosts. Not just the spirits of the thousands of Maine men who had died in the war—the victims of shot, shell or, more likely, disease—but also the ghosts of much younger men who had been replaced by the graying veterans staring back at him.

“The centuries to come will share and recognize the victory won here, with growing gratitude. The country has acknowledged your service. Your State is proud of it.”

After war had broken out in 1861, young men from all over Maine had joined the cause. Many of them felt compelled to do their part to restore the Union. Others felt the stirring of adventure, or the chance to see the world outside their own state. And there were even some who wanted to strike a blow against slavery, the root cause of the war. They came from all walks of life. They were farmers, lumberjacks, fishermen, sailors, students, lawyers, and teachers. For all of them, it’s safe to say, their experiences in the war had been transformative. Missing limbs and scars testified to the physical effects, but life as a soldier in the American Civil War left wounds that were harder to see, psychic scars that few people in the nineteenth century understood. Those who were lucky enough to survive returned to their homes and resumed their lives. Now they had come back to this small Pennsylvania town where so much blood had been shed to receive recognition for what they had done and endured.

“We do not claim a monopoly of the glory won on this field,” said Charles Hamlin, the son of the former vice president and an assistant adjutant general to Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys during the battle, when he addressed his fellow Maine veterans that night at Gettysburg. “But it is with justifiable pride, as we scan the line occupied by the living arch throughout the long three days’ contest, we note the pivotal points made memorable by the presence and conspicuous valor of Maine soldiers.” While it may be an exaggeration to say that Maine saved the Union at Gettysburg, its soldiers certainly played vital roles in the victory.

Selden Connor, who had been in command of the 7th Maine Infantry during the battle and, like Chamberlain, went on to serve as the state’s governor, also spoke to the gathered veterans that night in October 1889. “In proportion to the number of her troops in the action, no one of the eighteen states whose regiments flew the stars and stripes on this hard-fought field contributed more than Maine to the victory,” he said. “At whatever point the battle raged, the sons of the Pine Tree State were in the melee.”

Some 4,000 Maine men fought at Gettysburg over the three bloody days in July 1863. For many who survived, the battle remained the high point of their lives. Some talked about it until the day they died; others buried it deeply into their consciousness and tried to forget its horrific events. None of them emerged unchanged from the killing fields of Gettysburg. Whether they liked it or not, they had become a band of brothers. As Joshua Chamberlain told some of the survivors in October 1889, “Those who fell here—those who have fallen before or since—those who linger, yet a little longer, soon to follow; all are mustered in one great company on the shining heights of life, with that star of Maine’s armorial ensign upon their foreheads forever—like the ranks of the galaxy.”

Here are some of their stories, illustrated with cartes de visite courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.

Mending Fences after Cemetery Ridge

Seaman-turned-artilleryman Capt. Freeman McGilvery commanded the 6th Maine Battery before being promoted to lead an artillery reserve brigade in February 1863. The officer who expected to replace him in the 6th was 2nd Lt. Edwin B. Dow.

McGilvery fought to block the promotion. He informed Maine’s governor that Dow was “frequently intoxicated while on duty.”

Dow countered that McGilvery had whipped up the gunners of the battery into a state of near mutiny and threatened to press charges.

Then Gettysburg happened. On July 2, Dow still ranked as a lieutenant in temporary command. Later in the day, McGilvery reined up and requested Dow’s battery join a cobbled-together artillery line along Cemetery Ridge. After an intensive 90-minute action, McGilvery’s Plum Run Line stopped advancing Confederates until long-awaited Union infantry support arrived on the scene. The crisis was over and Cemetery Ridge saved.

Dow put aside any lingering personal feelings when he wrote his official report, “I deem it due to Major McGilvery to say that he was ever present, riding up and down the line in the thickest of the fire, encouraging the men by his words and dashing example, his horse receiving eight wounds, of which he has since died, the gallant major himself receiving only a few scratches.”

Dow advanced to captain, and McGilvery went on to become Chief of Artillery of the Tenth Corps. He died in early September 1864 from an overdose of chloroform during an operation to amputate a wounded finger that had not healed properly.

“Damned, Damned, Damned, God-Damned Son of a Bitch”

A Boston native and nephew of the mayor of Hallowell, Maine, Moses B. Lakeman was a carpenter by trade. He joined the 3rd Maine Infantry in the summer of 1861 as captain of Company I.

“Lakeman is a gallant officer, deserves such credit for his exemplary behavior, and should make an excellent Colonel, Lieut. Col. or Major,” said his division commander, Maj. Gen. David Birney, who added, “He has energy, and great decision of character.”

Lakeman fulfilled his promise, rising to the colonelcy and command of his regiment and leading it at Gettysburg into the fighting at Pitzer’s Woods and the Peach Orchard.

He also had a drinking problem. In October and November 1863, he faced court-martial proceedings on charges of being drunk on duty, habitual drunkenness and conduct unbecoming of an officer and gentleman.

On one occasion Lakeman, while under the influence, had taken umbrage when he felt that his second-in-command, Lt. Col. Edwin Burt, was usurping his position. Lakeman loudly declared that Burt did not “run this machine, and that he, Moses Lakeman did,” and loudly proclaimed that Burt “is a damned, damned, damned, God-damned son of a bitch.”

Burt testified that Lakeman made faces at him whenever he looked in the colonel’s direction. The charges didn’t stick, for Lakeman remained in his position.

The following year during the Overland Campaign, Burt was killed during the Battle of The Wilderness. Lakeman suffered a wound during the fighting around the North Anna River on May 23, 1864. He and his comrades mustered out a month later at the expiration of their enlistment.

Like Blades on a Pair of Shears

Waterville native Abner Small fought at the First Battle of Bull Run with the 3rd Maine Infantry, and then received the position of adjutant in the newly formed 16th Maine Infantry. He served in this capacity when the regiment was ordered by division commander Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson to hold its position along Oak Ridge on the afternoon of July 1.

“We were sacrificed to steady the retreat,” Small said. Another soldier from the 16th compared the situation to a pair of shears, with two blades closing in and the 16th Maine sent to the pivot point to keep them from snapping shut. As the Confederates tore into its position and the situation deteriorated, the Maine men determined that their flags would not fall into enemy hands.

“We looked at our colors, and our faces burned,” Small noted. “We must not surrender those symbols of our pride and our faith.” The soldiers tore up the flags and distributed the pieces among them. “These fragments were carried through Southern prisons and finally home to Maine, where they are still treasured as precious relics more than a quarter century after Gettysburg,” Small explained in 1889. Small was not among those captured at Gettysburg, but he spent time in Libby Prison later in the war. Today the Maine Historical Society has his scrapbook, which contains the star he kept from the regiment’s national flag.

Hot Smoke and Set Faces

Among the officers of the 20th Maine Infantry who fought at Little Round Top on July 2 were an educator and an attorney.

Ellis Spear, a schoolteacher from Wiscasset, was acting major. He was on the regiment’s left during the fight and remembered “uproar & earnest hot work.” He noted, “I smelt the hot smoke, the faces of the men were set. How they worked.”

Samuel Keene, the captain of Company F, had been lawyering in Rockland when the war broke out. He had been married for less than four months to Sarah Prince at the time of his enlistment. He kept a meticulous diary with succinct entries of each day’s events, noting the weather, his activities, the letters he sent and received, and the people he saw. He often complained of being “blue” and of longing for home.

Both men survived the ferocious fighting at Gettysburg. But less than a year later outside Petersburg, a sharpshooter’s bullet struck Keene. He died in Spear’s arms. Spear reported that his last words were, “Write to my wife. It is all well. I die for my country.”

Ten years later, in 1874, Spear’s wife died. He married Keene’s widow.

“Come on! Come on! Come on boys!”

A farm boy from Topsham, Holman Melcher graduated from the Maine State Seminary (later Bates College) in Lewiston. When he mustered into the 20th Maine Infantry as a corporal, he had just turned 21, and taught school.

At Gettysburg, Melcher served as first lieutenant of Company F, which was charged with the regimental colors on Little Round Top. When the Alabamians pushed the Union line back, he was distressed to see that some of the Maine dead and wounded now lay between the contending lines, where they were exposed to fire from both sides.

Melcher approached Col. Chamberlain and suggested moving his company forward to cover the wounded. Chamberlain gave the order and Melcher took off. “With a cheer and a flash of his sword that sent an inspiration along the line, full ten paces to the front he sprang—ten paces—more than half the distance between the hostile lines,” wrote Theodore Gerrish in his history of the regiment. “‘Come on! Come on! Come on boys!’ he shouts. The color sergeant and the brave color guard follow, and with one wild yell of anguish wrung from its tortured heart the regiment charged.”

Behind Enemy Lines

A law student in Dixfield, George Bisbee enlisted as a first sergeant in the 16th Maine Infantry in June 1862. Shot in the arm at the Battle of Fredericksburg, he went to extraordinary lengths to rejoin his regiment before the fighting at Chancellorsville, including finding Vice President Hannibal Hamlin in Washington, D.C., to get a pass to the front.

By the start of the Gettysburg Campaign he had been promoted to second lieutenant. Bisbee was captured on July 1 and held behind Confederate lines. On July 3, Bisbee recalled, he saw Maj. Gen. George Pickett ride by before he led his division on the attack that Gen. Robert E. Lee hoped would break the Union center.

Bisbee heard the cannonade that preceded the attack and listened to musketry as the two infantries clashed. All he could see of the battle was smoke rising in the distance. The suspense was excruciating. He learned that Union forces had won the day after Pickett’s soldiers came stumbling back out of the smoke, “bloody, wounded, straggling, and in short all cut up and with hardly any resemblance to the brave men who so boldly went out a short time before.”

On the night of July 4, as rain poured down, the captured members of the 16th and the rest of the Union prisoners were placed in the rear of the Southern army to begin a weary march south. “While we rejoiced over the defeat of Lee’s army and the success of the Union troops it was a sad march for us prisoners,” Bisbee said. He spent most of the rest of the war in enemy hands.

Blazing Away in the Wheatfield

Vermont-born Charles Mattocks moved to Baldwin, Maine, when his widowed mother remarried a local man. At the start of the war, Mattocks attended Bowdoin College, where Joshua Chamberlain was one of his professors. Upon his graduation in 1862, he joined the 17th Maine Infantry as a first lieutenant.

Young, ambitious and intelligent, he earned a reputation as a disciplined soldier, though enlisted men found him aloof. “I can’t think of any officer I’d sooner part with, for he was very pompous and had yards and yards of superfluous red tape about him,” one private noted.

On July 2 at Gettysburg, Mattocks and his comrades defended a stone wall in the Wheatfield. Mattocks had three men loading muskets for him while he blazed away from behind the wall. Two men were shot and killed beside him. Captured at the Battle of The Wilderness in 1864, Mattocks eventually gained his release and returned to his regiment.

His gallantry at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Va., on April 6, 1865, earned him the Medal of Honor. He ended the war as colonel and brevet brigadier general.

Tom Huntington was born in Maine but now lives in Pennsylvania. The former editor of American History and Historic Traveler magazines, he has also written Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg and Guide to Gettysburg Battlefield Monuments.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.