New Jersey native John Kuhl discovered his passion for Civil War soldiers from his home state in a most unlikely place— a navy vessel in the Antarctic during the 1950s. In between duty as deck officer and navigator, he read a lot of books. One in particular stuck with him: A volume about the Civil War that contained a reference to a Paul Kuhl.

The name roused his curiosity. Upon his return to the States, Kuhl traced the man’s genealogy and found they were distantly related. Kuhl, in fact, had a lifetime fascination with the Civil War that began in his childhood. It deepened through his years as a navy midshipman at Penn State, his tenure as a naval officer, and his career in commercial agriculture in the northwest part of the Garden State.

Kuhl bought his first war relic, a musket, in 1953. More than two decades later, in 1976, the wife of a late friend gave him a few cartes de visite of New Jersey soldiers. He’s been collecting them ever since.

Here are representative examples from his collection of Jerseymen.

Unique Hat Brass

As far as hat brass is concerned, New Hampshire soldiers stand out among the Union states for the ubiquitous NHV attached to their caps. But here is an example from New Jersey—Pvt. William H. Estell, who served in Company D of the 14th Infantry. He died at Spotsylvania Court House on May 13, 1864, and his remains rest in the national cemetery at Fredericksburg, Va.

Mortally Wounded at Fredericksburg

As an expression of respect and admiration, the men of the 4th New Jersey Infantry presented their colonel, William B. Hatch, with a dappled horse named “Grey Warrior.”

Hatch had a lifelong fascination with army life. Prior to the war he toured Europe to observe military systems. After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, he promptly enlisted in the 4th New Jersey Militia for a 3-month term. When the new 4th Infantry organized for three years, he became the regiment’s major. Captured with his men during the Battle of Gaines’ Mill in July 1862, he advanced to colonel upon his release, and commanded at the Battle of Fredericksburg on Dec. 13, 1862. Here, he fell with a severe leg wound leading a charge at the head of his troops during an assault against Confederates at Marye’s Heights. Hatch suffered an amputation at the thigh, and succumbed to its effects two days later.

Grey Warrior survived and became the property of cavalry Brig. Gen. Alfred T.A. Torbert. The horse died in 1882, outliving Torbert by two years.

Artist Artilleryman

In June 1863, Harper’s Weekly illustrator John R. Chapin exchanged the tools of his trade for a sword to repel Confederate invaders in Pennsylvania. He captained a light artillery battery that took his name, and, with other emergency militia infantry from New Jersey, crossed into the Keystone State to fight. Assigned to the defenses of Harrisburg, Chapin and his gunners served a 30-day enlistment. Though they never faced the enemy or mustered for federal service, Chapin and his comrades left knowing that they stood up and did their part for the cause. Chapin returned to his work as an artist, and died in 1907.

Trenton Oasis

After a six-day journey by foot, train and ship, the veterans of the 14th New Jersey arrived in their state capital to muster out of the army after completing their 3-year term of enlistment. At midnight on June 22, 1865, “these heroes of many battles marched through the dark and silent streets of Trenton to the ‘Soldiers’ Rest,’ where, a few hours later, they were welcomed by patriotic ladies, who entertained them at breakfast,” noted the regimental historian. It is easy to imagine the tables in this undated view piled high with food for the hungry men and those of other New Jersey regiments.

“How Are You, Butterfly?”

As the war progressed, attracting quality recruits became more challenging. In late 1863, organizers of one Union regiment hoped to appeal to recruits through dramatic dress in the ancient Hussar tradition. The 1st United States Hussars, or 3rd New Jersey Cavalry, wore uniforms crawling with braid, buttons and trim, and finished with sideways, brimless caps and short cloaks, or talmas. They were regarded with awe by some, and ridicule by others, who nicknamed them the Butterflies in light of the preponderance of yellow lace.

“Expressions like this might often be hard on the march. ‘There goes a butterfly, ketch him and put him in a canteen!’” chided one New Jersey newspaper. The reporter went on to share an exchange between one of the Hussars and a member of the 2nd New York Mounted Cavalry. The New Yorker, a soldier boy, “looked up, and in a quiet way saluted the Third New Jersey with, ‘How are you, butterfly? Third New Jersey turned partly around in his saddle, with a smile, and saluted with, ‘How are you, caterpillar?’”

Military Professor in Training

Capt. George Patten, a South Carolina native who had served in the Mexican War, survived his enlistment as a Butterfly and became a professor of engineering at Pennsylvania Military College. He died in 1890.

Going Full Talma

The talma, a short cloak worn by troopers in the 3rd New Jersey Cavalry, is often pictured in portraits as unbuttoned with the hood hidden from view. This example pictures the garment, copied from a French design and fashioned from sky-blue kersey with a bright orange lining, in full form. The sight of this unidentified soldier and his comrades in the regiment riding with their talmas fully deployed must have been a real attention grabber.

Loyal Aide-de-Camp

First Lt. James H. Demarest of the 8th New Jersey Infantry served on detached duty as a trusted aide-de-camp to a fellow Jerseyman, Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott. During the waning days of the Confederacy, Demarest impressed Mott with his courage in two 1865 engagements—the attempted Confederate breakout at Fort Stedman on the Petersburg front on March 25 and the Battle of Amelia Springs on April 6. Mott recommended a promotion for Demarest, who received a captain’s brevet in honor of his meritorious conduct. He lived until 1883.

Honored Chaplain

In May 1862, Rev. Dr. Julius David Rose of the 7th New Jersey Infantry missed the annual convention of the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey for the first time in many years. The reason? The 37-year-old German-born minister had become an army chaplain. Instead, he sent a written report, in which he noted, “My labors thus far have been blessed. The attendance of services during the winter averaged from 400 to 500. I administered the Holy Eucharist several times to great numbers. I buried, I am sorry to say, about 125, many of which showed a decidedly Christian character, and died in the Lord.”

Rose filed another written report in May 1863. By this time, he suffered from malarial fever. Still, he accompanied his regiment through the Battle of Gettysburg. But on the return trip to Virginia, he fell victim to sunstroke, which, with his other ailments, prompted his resignation in September 1863. At some point, he posed for this portrait wearing three medals pinned to his uniform. The decoration on the right is the Kearny Medal.

Back in New Jersey, Rose returned to his flock at St. Matthew’s Church in Newark. He left in 1869, became an educator and founded two schools. He died in 1890 at age 66.

Defending Bliss Barn

At Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, Capt. Henry Franklin “Harry” Chew of the 12th New Jersey Infantry and his comrades dashed beneath the scorching sun towards a barn belonging to William and Adelina Bliss. The fortress-like structure had narrow windows perfect for sharpshooters. Chew and an orderly sergeant took up a position along a fence as enemy artillery boomed. The sergeant suggested that they move out of harm’s way. Chew replied, “We are as safe here as any where, you can’t run away from them things.” At that moment, a solid shot crashed into and knocked a picket out of the fence, against which the orderly sergeant leaned. Chew shouted, “Get out of here,” and the pair ran to the barn.

Chew, a Quaker who suspended his beliefs to fight, narrowly avoided a wound on this occasion. He was not so lucky a year later in The Wilderness, when he suffered a gunshot wound to the right elbow. He soon returned to duty, and participated in the Petersburg and Appomattox campaigns. After the war, he returned home, married and fathered two daughters. Active in veteran’s affairs, he helped establish a regimental memorial at Gettysburg. Chew died in 1907 at age 80.

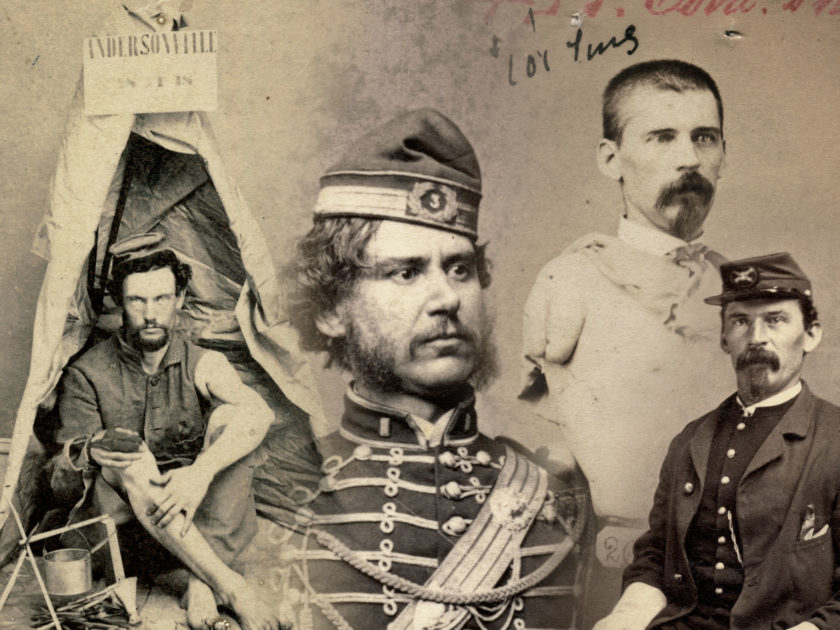

Carrying the Colors at Spotsylvania

Cpl. Joseph G. Runkle, standing above right, of the 15th New Jersey Infantry color guard, made the ultimate sacrifice on May 12, 1864, at Spotsylvania. He “had his right arm pierced by bullets, and it fell paralyzed by his side. He continued to carry the colors with his other hand, until the contest ended. He died from his wounds, at the hospital in Washington, June 7th. He was a young man of more than ordinary promise,” noted the regimental historian, “Feeling it his duty to enter the service of his country, no earthly consideration could dissuade him from it.” Runkle was 19.

His pard, Albert H. Kingman, served as a private in the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters. He mustered out of the army a few months after Runkle died and lived until 1908.

Before the Terrible Swift Sword

The 15th New Jersey Infantry went into winter quarters near Brandy Station at Freeman’s Ford, along the Hazel River in Virginia, in December 1863. According to the regimental history, “The camp of our brigade was in a pleasant situation, on a number of rolling hills five miles from the railroad and on the extreme right of the army. Good water was convenient and timber abundant. The men built small log houses for themselves, and roofed them with the pieces of their shelter tents.”

Sometime between January and March 1864, these groups of officers and non-commissioned officers posed for their portraits by Weitfle and Wright, both civilian photographers approved by the Army of Potomac.

The good times would soon end. On May 4, 1864, the 15th left its quarters and crossed the Rapidan River with 15 officers and 429 muskets. About 300 became casualties at Spotsylvania on May 12. Among the 116 killed or mortally wounded: 1st Sgt. Paul Kuhl of Company A, to whom the caretaker of these photographs is connected on the family tree.

The 15th is listed as one of Fox’s 300 Fighting Regiments. Only 11 of 2,200 Union regiments suffered more battle casualties than these Jerseymen.

Struck by a Shell as He Sighted a Gun

Julius George Tuerk is pictured before and after Confederates made a final desperate attempt to break the Siege of Petersburg on March 25, 1865. The German-born first lieutenant and his comrades in Battery C of the 1st New Jersey Light Artillery happened to be in Fort Haskell when the Southerners struck. A shell struck Tuerk as he sighted a gun, tearing off his right arm. The loss of a limb did not prevent him from returning to the army as quartermaster of the 114th U.S. Colored Infantry. After his service ended in 1867, he and his wife, Louisa, settled in Davenport, Iowa, where he died in 1886.

A Hero of New Orleans

Career navy officer Charles Stewart Boggs brought more than three decades of experience to bear when he was named commander of the 150-man gunboat Varuna after the start of the war. On April 24, 1862, his vessel became the first of Rear Adm. David Farragut’s fleet to make it through heavy fire from Confederate Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip on its way to New Orleans. The Varuna cleared the forts, only to run straight into a hornet’s nest of enemy vessels. Boggs fired everything he had at the ships. When it was all over, the Varuna went down with flag flying—but only after it destroyed four vessels and contributed to the destruction of two others.

Boggs and most of his crew survived the sinking. They became heroes, and made headlines in newspapers across the North, and even inspired a poem. Boggs received a promotion and a new vessel, and fought on through the war’s end. He retired in 1872 as a commodore. He died five years later.

Battlefield Promotion

Few soldiers received promotions for gallantry on the battlefield. Here is one of them—William Gillon Thompson of the 6th New Jersey Infantry. While serving as an aide-de-camp to Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott during the Battle of Chancellorsville, 2nd Lt. Thompson suffered a severe wound, and received a promotion to first lieutenant. A Pennsylvania native educated at Amherst College, Thompson had served in the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry prior to joining the 6th. He survived his wound, mustered out in September 1864, and went on to become a two-term mayor of Detroit. Baseball buffs may remember him as the man who founded the first professional team in Detroit—The Wolverines. Thompson lived until 1904.

All in the Family

Army and Navy surgeons with a New Jersey connection pose with their wives in New Orleans, La. The naval officer is Benjamin Franklin Gibbs of Pemberton, N.J., who began his military career in 1858. He served through the war, notably aboard the Ossipee during the Battle of Mobile Bay. That same year he married the woman standing next to him, Elizabeth Beatrice Kellogg, who glances downward upon a letter held by her mother, Lydia. White-bearded George M. Kellogg, wife of Lydia and father of Elizabeth, stands off to the side. During the war, he served as medical director on the staff of Maj. Gen. George Crook.

After the end of hostilities, George remained in the navy and advanced to medical director and fleet surgeon of the European Squadron. In 1882, he died on duty in the Italian seaport of Trieste after a brief illness. Navy officials sent his body to Washington, D.C., for burial. His distraught wife, Elizabeth, committed suicide a year later when she jumped from the window of a moving train. Both her parents and two children survived her.

Well-Traveled Portrait

Dr. Alvin Satterthwaite carried this portrait of his wife, Jennie, through more than a dozen battles—from Chancellorsville through the Petersburg and Richmond Campaign. The couple had married in Philadelphia in August 1861, soon after Satterthwaite returned from a 3-month enlistment in the 4th New Jersey Infantry. After the wedding, he returned to the army with the 7th New Jersey as its assistant surgeon, and went on to become the surgeon of the 12th New Jersey Infantry. He mustered out in June 1865, and returned to his wife in Mount Holly, N.J., where he died in 1873.

Phil Kearny’s Nephew

Capt. Philip John Kearny of the 11th New Jersey Infantry was cut from the same military cloth as his illustrious uncle, Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny Jr. At first, it seemed their name was the only thing the two men shared in common. Gen. Kearny dismissed his captain-nephew as ill-suited for combat. The captain’s men thought him arrogant and too harsh a disciplinarian. Attitudes towards young Kearny softened, however, after he proved his courage at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, earning a major’s brevet for the latter action.

On July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg, a rebel bullet lodged in Kearny’s knee during the fighting in the Peach Orchard. He underwent an amputation and succumbed to its effects after a month of suffering. He was 21. The historian of the 11th noted, “In the death of Major Kearny the regiment lost one of its best officers.”

“Andersonville As It Is”

The words on a sign above this lean-to suggest this is a realistic recreation of life inside the Union prisoner of war camp in Georgia. The ragged soldier, huddled beneath his makeshift tent with a primitive cooking setup, may have been a survivor.

His portrait is a reminder of the 235 Jerseymen reported to have died at the camp. In 1899, a monument was erected on the grounds to honor them. Inscribed on it is a verse inspired by the “Go tell the Spartans” memorial at Thermopylae:

Go, stranger, to New JerseyTell her that we lie hereIn fulfillment of her mandateAnd our pledge,–to maintain theProud name of our State unsulliedAnd place it high on the scroll of honorAmong the States of this Great Nation.

“John Emery, My Jo”

The inscription below this portrait of John Runkle Emery plays on the lyrics of a popular song, John Anderson, My Jo, from a poem by Scottish bard Robert Burns:

When art at first began to try her canny hand, John, her master work was man

And you among them a’John, so trig from top to toe,

She proved to be her first attempt, John Emery, my Jo.

Emery joined the 15th New Jersey Infantry as the second lieutenant in August 1862 and left six months later due to illness. He lived until 1916.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.