By Brian Boeve and Rusty Hicks

Some men were made for high rank, destined for renown as commanders who basked in glory in momentous battles.

Others refrained from senior leadership, preferring to remain among the soldiers in the ranks. Many of these men were no less courageous than the famous generals. And yet, they are little remembered, if at all.

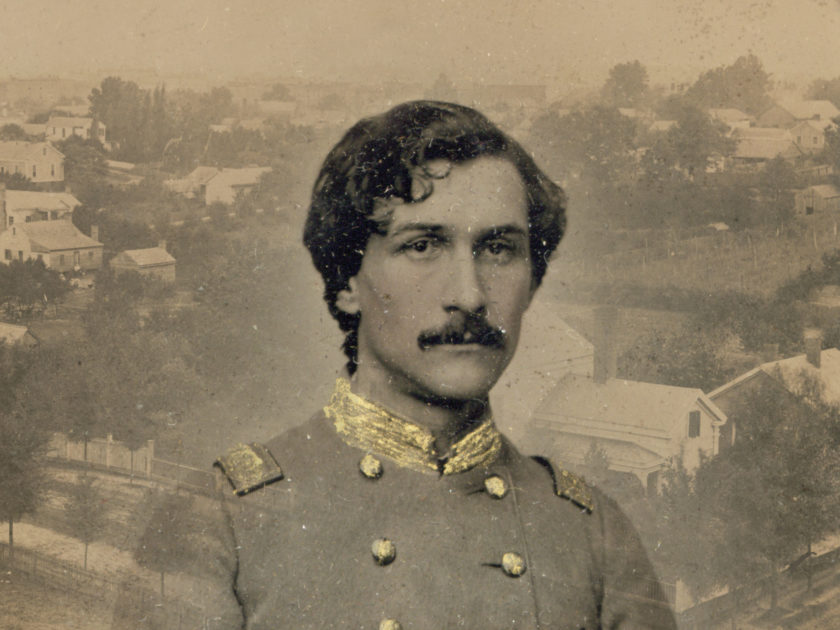

One of these unknowns became an unlikely Confederate warrior—a bookish, retiring and reclusive Kentuckian with a marvelous military name, Lafayette Hewitt.

Born in 1831 in Hardin County, “Fayette,” as he was familiarly known, moved with his family to Elizabethtown as a young boy. His father, Robert, the principal of a local academy, instilled his son with a fondness for academic study that ultimately contributed to the completion of his college studies at age 16. His father’s untimely death the following year left Hewitt, now 17, as the man of the family, which included his widowed mother and five siblings. He accepted his late father’s position as principal, and might have remained in the job for the rest of his days. But, health issues prompted him to seek a more hospitable climate in the Deep South.

Hewitt settled in Louisiana about 1857, but did not stay long. Two years later, fellow Kentuckian Joseph Holt, Postmaster General in the administration of President James Buchanan, offered Hewitt a job as superintendent of the Dead Letter Office in Washington. Holt, a lawyer and newspaperman prior to joining Buchanan, had once lived in Elizabethtown. He likely came to know the Hewitt family during that time.

Hewitt accepted the position, and moved to Washington as a deeply divided nation entered the 1860 presidential campaign season. The result of the election stirred Hewitt into action. According to a biographer, he “resigned that position on President Lincoln coming into power. And the war breaking out, he espoused the cause of the Confederacy.”

About a hundred miles south in Richmond, Confederate Postmaster General John H. Reagan moved swiftly to build a department from scratch. He poached numerous officials from his counterparts in Washington. Reagan became aware of Hewitt’s situation and telegraphed him to come to Richmond. “Accordingly, he went and received the necessary appointment and went to work in earnest,” noted the biographer.

Back in Washington, President Lincoln worked to put down the rebellion and fretted about further threats of secession. “Mr. Lincoln’s solicitude was deepened by the dubious, vacillating attitude of the Border Slave States, especially of his native Kentucky, which he was particularly anxious to attach firmly to the cause of the Union, while she seemed frantically wedded to Slavery,” reported New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley.

Lincoln’s sentiment was captured in a quip reportedly made by him to a group of ministers who sought to reassure him that God was on his side should he free the slaves. “I would like to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

“He became as dear to me as my own sons. Brave, courteous, amiable, unassuming, obliging, and kind to every one, firm in the performance of duty—a nobler gentleman or better soldier never lived.” —Gen. Albert Pike

Although Kentucky ultimately adhered to the Union, approximately 25,000 of her sons joined the Confederate Army. Considering the 90,000 Kentuckians who enlisted in the federal army, this border state was indeed a brother’s war.

The most prominent Confederate military organization raised in the state was the Kentucky Brigade. Five regiments strong, it became known after the war as the Orphan Brigade, when a devastating assault against Union forces at the Battle of Stones River on Jan. 2, 1863, decimated its ranks. Maj. Gen. John C. Breckenridge, upon seeing the tattered remnants of his command, broke into tears. “A sorrowful expression escaped his lips, to find, as he said, his ‘poor Orphan Brigade torn to pieces,’” reported the brigade historian.

As the Kentuckians rebuilt their fighting force, Hewitt joined them with a desire for field duty. In late 1861, he resigned his post office position and accepted an appointment as Assistant Adjutant General with the rank of captain. Ordered to the Trans-Mississippi Department, he spent more than a year on the staffs of generals Albert Pike, Thomas C. Hindman, Theophilus H. Holmes and John G. Walker.

Hewitt especially impressed Gen. Pike, who observed, “He daily deserved praise, and won the love and admiration of all who knew him. He became as dear to me as my own sons. Brave, courteous, amiable, unassuming, obliging, and kind to every one, firm in the performance of duty—a nobler gentleman or better soldier never lived. If he has a vice, a fault, or a failing, I never discovered it; and there is no knightly virtue or excellence with which his character is not adorned. A more gallant soldier there never was—gallant with the cool, reflective courage of a gentleman and man of honor.”

In February 1863, Hewitt served briefly with Breckenridge before transferring to the staff of Brig. Gen. Benjamin H. Helm, who commanded the Orphan Brigade. The Kentucky-born Helm, a West Pointer, Harvard-educated lawyer and politician, was married to Emily Todd, the half-sister of Mary Todd Lincoln.

Hewitt faced his baptism under fire with the Orphans at the battles of Jackson, Miss., and Chickamauga, Ga. During the latter engagement, Gen. Helm suffered a mortal wound. The Lincolns received word of his death with great sadness, with the president visibly moved upon receipt the news.

Hewitt received praise for his leadership at Chickamauga in an official report by Col. Joseph H. Lewis, who took command of the Orphans after Helm fell. “As soon as he was enabled to do so he reported to me, and throughout the entire action,” Lewis wrote. “He displayed gallantry, coolness and judgment.”

Less than a year later, during the Battle of Atlanta on July 22, 1864, Hewitt’s soldierly qualities impressed an unnamed officer from the 5th Kentucky Infantry. The officer recalled, “The nature of the ground and the furious reception with which we were met, as soon as the Federals caught sight of us, and the withering fire under which we tried to press forward, had the effect of throwing our brigade too much in a mass to the left and the situation was dangerous in the extreme. We were being destroyed while in poor shape of returning fire. Hewitt came from the right fearfully exposed, but not only was his arrival opportune, but his cool judgment grasped the situation in a moment. He saw the remedy and we were extricated. It was a display of qualities of which real generals are made.”

“I do wish I could bear myself like that man Hewitt. He rode down there into the jaws of that hell on the left, to get us out of the tangle, composed and smiling.”

Though Hewitt may have possessed skills for higher command, he did not seek promotion. When a major general in the Army of Tennessee sought to elevate Hewitt to colonel, and assign him as his chief of staff in 1864, Hewitt declined. He reportedly told that general that he would rather remain captain among his fellow Kentuckians of the Orphan Brigade than a general of any other brigade in the army.

Another anecdote from the Battle of Atlanta illustrates Hewitt’s compassion for his Kentucky brothers. As the fight prepared to commence, Hewitt noticed a soldier set aside his blanket. The man explained that he preferred to fight without being encumbered by the blanket. Hewitt replied that should the soldier be wounded, he would certainly have use of the blanket. With that, Hewitt tied the blanket beside his saddle, in case the soldier would need it later. During the battle, Hewitt’s horse was torn apart by a shell. Hewitt, uninjured, untied the blanket, tossed it over his shoulder and carried it until another mount was found for him. He rode on, encouraging his boys forward, into the fray.

Through it all, he carried the blanket.

Hewitt happened upon its owner at a field hospital after the battle. The grateful soldier was amazed that the captain had remembered the blanket.

Later that night in another section of the battlefield, a group of Kentuckians bivouacked in an open field. A gloom had settled over them as they reflected on the days’ disaster, over scant rations and an open fire. Hewitt came by, sensed the sour mood, and attempted to cheer them with a story.

Hewitt told them that he had just come from a group of Kentuckians from the 9th infantry. They did not recognize him. As he mingled with the men, Hewitt overheard two of the officers talking, with one remarking to the other, “I have courage enough to stay and try to do my duty when fighting has to be done, but I do wish I could bear myself like that man Hewitt. He rode down there into the jaws of that hell on the left, to get us out of the tangle, composed and smiling. I like it.” Hewitt, with characteristic modesty, did not reveal his identity. He did however, think to himself, “My friend, if you only knew how badly Hewitt was scared you wouldn’t like it!”

Hewitt remained on duty with the Orphans through the rest of the war, losing two more horses in battle and having numerous shots pass through his clothing, hat and even his hair. He surrendered with survivors on May 7, 1865, at Washington, Ga. Though exact details of his whereabouts are not known, the time and place indicate that he accompanied Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his entourage as they fled the fallen capital.

As with many veterans, Hewitt returned home to build a new life. Back in Elizabethtown, he held a temporary position as head of an academy for young women, and also practiced law. In 1867, he accepted an appointment as the state’s Quartermaster General, and collected more than two million dollars from the federal government to settle the state’s war debt. As an officer of the Kentucky Soldier’s Home, he fought for aging veterans. He went on to be elected three times as State Auditor, and finished his career as the president of the State National Bank in Frankfort. He never married.

Hewitt’s death at age 77 in 1909 was mourned by many at a time when North and South still struggled to bind the nation’s war wounds. Among those who attended his funeral was Emily Todd Helm. The Kentucky State Historical Society passed a series of resolutions to honor his life. One resolution included this passage: “Nearly fifty years ago, it was given to this nation that they pass through a period of travail. Devastating war laid waste to a part of this fair land. All the passions that sway men’s souls united in the great sacrifice and from out the ashes there sprang up a set of men, tempered by the fire of experience, true as steel. These men are passing away from us, and to those who know their worth and love them, each death recorded adds a weight of woe, and one of these was Fayette Hewitt. Patriotism with him was not a mere rhetorical expression, but a deep-seated, passionate instinct. Kindness with him was not incidental, but an ever present beneficial influence. Truth shone in his countenance and lighted the way through all the days of his life.”

An obituary in Confederate Veteran added, “In his death Kentucky lost a splendid citizen and many citizens lost a perfect friend.”

Perhaps Hewitt’s most enduring legacy was a donation he made to the U.S. War Department in 1887—thousands of pages of original reports, correspondence and other papers related to his beloved Orphan Brigade. Housed in the National Archives, they serve as a primary resource that tells the story of this unique border state military organization.

References: Samuel Haycraft, A History of Elizabethtown, Kentucky; Horace Greeley, The American Conflict, Vol. II; Edwin Porter Thompson, History of the Orphan Brigade; Battle, Perrin and Kniffen, Kentucky: A History of the State; Zachariah Frederick Smith, The History of Kentucky; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; William C. Davis, The Orphan Brigade: The Kentucky Confederates Who Couldn’t Go Home; “Gen. Fayette Hewitt,” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 17; Unfiled Papers and Slips Belonging in Confederate Compiled Service Records, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Brian Boeve is an MI Senior Editor and Rusty Hicks is a Contributing Editor. Both are longtime collectors and frequent contributors.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.