By Scott Valentine

On an inclement December eve at a Grand Army of the Republic meeting about 30 years after the war, veteran Josiah Murphey experienced a dull ache in his right cheek. The pain was all too familiar. He had felt it for years.

The source, a deep scar, marked the location of a battle wound he had received many Decembers earlier. The pain that emanated from it often caused Josiah Murphey to relive the grim details of the fight and his military service.

In the summer of 1862, Murphey—all 5-feet-3 ½ inches of him—was only 16 years old when he left his home on Nantucket Island, Mass., and joined the army. Because of his tender age, Murphey needed and received his parent’s permission to enlist. Full of patriotism and ready to take on the Rebs, he later likened his fervor to an ailment, stating that he had “caught the fever.”

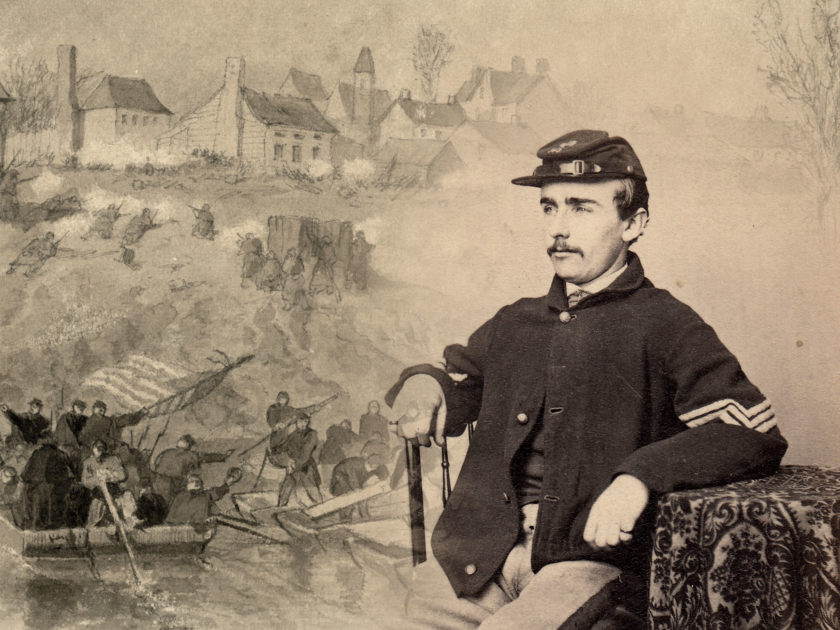

Murphey enlisted in Company I of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, nicknamed the “Harvard Regiment” because so many of its officers were educated at the college.

During the next three years, the regiment would become known as the “Bloody 20th” in recognition of its high casualties, the fifth highest of 3,000 regiments in blue.

The men of the 20th Massachusetts had a tough time from the start in 1861. They saw hard service at Ball’s Bluff, White Oak Swamp, Glendale, Malvern Hill and Antietam.

Murphey missed all these engagements. But he would be present for the regiment’s toughest test at the Battle of Fredericksburg, and would later tell his story.

During the early morning hours of Dec. 11, 1862, Murphey had just fallen to sleep along the fog-enshrouded Rappahannock River when he and the rest of his company were ordered to be ready to move in about an hour.

By this time, rumor held that the overall commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, planned to cross the Rappahannock and attack the town of Fredericksburg, defended by Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

Murphey and his comrades could not have known the battle was lost before it began. Burnside’s original concept relied on swift movement and deception to catch his adversary off guard. But weeks had passed as pontoon boats were brought into position for the crossing. Lee took advantage of this and other delays to prepare for the assault.

By the time Burnside moved, Lee had fortified his position on the river’s west bank, notably along a sunken road perched above the town on Marye’s Heights.

Burnside’s engineers began to lay the pontoons under the cover of the early morning fog on December 11. But the fog lifted by mid-morning, revealing that only one of five bridges was partially constructed. Confederate sharpshooters, Mississippians and Floridians under Gen. William Barksdale, made life difficult for the unarmed engineers, who hightailed it back to the safety of the east bank of the Rappahannock.

After Union artillery perched on Stafford Heights failed to drive Barksdale’s sharpshooters from the shoreline, Burnside asked for volunteers to cross the river in pontoon boats and drive away Barksdale’s sharpshooters. One brigade commander, Col. Norman J. Hall, offered his five infantry regiments, which included his own 7th Michigan. The others were the 19th Massachusetts, the 59th New York, the 137th Pennsylvania—and the 20th Massachusetts.

Word of the assignment circulated swiftly through the ranks. Murphey later recalled: “Well we knew what was in store for us, we knew that we were to make an attempt across the river and gain the city and the heights beyond, and knowing how strongly fortified the rebs were, we knew what a reception we should get, and that many of us would never see the light of another day.”

The men of the 7th Michigan ferried over first, and, after a brief firefight, secured the riverbank and sent Barksdale’s sharpshooters scampering up into the streets of Fredericksburg. A half-hour later, the 19th Massachusetts followed, and both regiments fanned out along the street above the river. By the time Murphey and the 20th Massachusetts readied to cross, the wounded of the 19th Massachusetts and 7th Michigan were being ferried back from the shoreline opposite. The pontoons pulled up and unloaded the injured.

Now, the time arrived for Murphey and the rest of the 20th Massachusetts boys to cross. Murphey later recalled that, “When we crossed the Rappahannock river in boats at the assault on Fredericksburg, it was necessary to push the boats a little way from the shore to prevent their grounding when we got into them. The shore was fringed with ice and we with shoes on, of course, we were wet above our ancles and with no chance to dry them.

After getting into the boat two men sat down at the oars. One was Thomas Russell of this town [Nantucket], the other man I do not remember, but he pulled Russell right around and headed the boat upstream. Lieut. Leander F. Alley said to me, ‘Murphey, take that oar,’ which I did and we soon had the boat across on the other side where she grounded a few feet from the shore. We jumped out and waded to the land.”

They soon joined their comrades in the 19th Massachusetts and the 7th Michigan, and awaited further orders.Meanwhile, engineers completed construction of the pontoon bridge, and the free flow of Union forces began in earnest.

“We lay under the bank of the city and as soon as the troops began to cross we were ordered forward,” Murphey remembered. “Our company formed in two platoons of about thirty men each at the lowest end of a street called Farquier street and began our advance up the street.”

“As soon as we came in sight of the rebels who were concealed in every house and behind every fence, they opened a terrible fire on us at short range”

Though Murphey had misidentified the street—Hawke Street—he and the rest of the men soon discovered that they occupied a precarious position.

“As soon as we came in sight of the rebels who were concealed in every house and behind every fence, they opened a terrible fire on us at short range and our men began dropping at every point, those struck in the vital parts dropping without a sound, but those wounded otherwise would cry out with pain as they fell or limped to the rear,” Murphey reported. “But despite the terrible fire we pressed on up the street. Where men fell and left a vacant place other men stepped into their places and although death stared us in the face there was not a man who faltered. Our chief company officer Capt. H.L. Abbott said, ‘… hold your fire, boys, until you see something to fire at.’”

They moved up Hawke Street toward its intersection with Caroline Street. “We had now arrived at the corner of a cross street and I, being on the left flank of the company, turned to look down the street to see if anything could be seen to fire at, and bringing my gun to the ready at the same time,” Murphey recounted. “At that moment, I felt a sharp stinging pain on the right side of my face and presto, I knew no more. …When I came to I was lying on the ground where I had fallen, and the company had advanced a short distance up the street. The balls were still flying thick around me and I realized I was wounded. I clapped my hand to my face to stop the flow of blood but it was no use. It flowed between my fingers and down onto my clothing.”

Murphey had just joined the list of 97 men killed and wounded in the intense street fight that lasted no more than a few minutes. Casualties included Pvt. Thomas J. Russell, one of the rowers in the boat. According to a corporal from the 19th Massachusetts, who was eyewitness to the action, “I saw the 20th make this desperate march, with no definite end in view as far as anyone could see, into the most useless slaughter I ever witnessed. It was a wonderful display of orderly movement by a body of men of unsurpassed courage and coolness.”

The bullet that struck Murphey tore into his right cheek and had sliced along a couple of inches of flesh, carrying away bone tissue and permanently impaired his right eye. Drenched in blood and feeling faint, he stumbled down Hawke Street and back across the river to a field hospital quartered at the Lacy House. Upon reaching the relative safety of the hospital, Murphey thought his ordeal was over.

It was not.

“A nurse came along and said he would take a few stiches in my wound for me. He went off to get his needle and I never saw him afterwards. …Think of it, wounded and unable to help yourself, and lying on the ground in the month of December with only a rubber blanket between you and the cold earth,” Murphey noted. “The first night I spent in the Lacy House hospital opposite Fredericksburg was an awful night. Men were brought in at all hours with all kinds of wounds and groaning terribly. Others were brought in from the battlefield insensible but also groaning with pain. Those that died during the night were carried out and laid on the ground to make room for others.”

He passed a second night in the uncomfortable conditions, and awoke to the sound of cannonading on December 13. The hospital stood in the line of fire. “A rebel solid shot struck it and made it tremble all over,” Murphey recalled. “It did no damage as far as I know but we held our breath expecting every minute another would come tearing through the walls and perhaps into the room where we were lying, but none others struck us.”

Murphey’s injury caused him to miss the horrific fighting along Marye’s Heights. Others in his regiment were not so fortunate. Many more fell in the failed assault to dislodge its well-entrenched defenders. One of those was the second lieutenant in command of Murphey’s company, Leander F. Alley. A much-beloved officer who hailed from Nantucket, he had ordered Murphey to grab an oar and row just two days earlier. Now, he lay dead with a bullet through the left eye. Murphey was tasked with escorting his fallen lieutenant’s remains home.

Total casualties for the 20th at Fredericksburg reached 238.

Murphey rejoined his regiment by March 1863, and in May took part in the Battle of Chancellorsville. In late June, Murphey and the regiment matched into Pennsylvania to counter Gen. Lee’s second northern invasion that would result in the Battle of Gettysburg.

“We had some terrible forced marching, often thirty miles a day, and were kept at it through mud and rain,” Murphey remembered. “I took a severe cold by having to sleep in wet clothes and was ordered to the hospital.” In fact, he had contracted typhoid fever and spent most of the next four months hospitalized in Alexandria, Va.

Murphey reunited with the regiment again in October 1863. Promoted to orderly sergeant, he briefly commanded Company C and E before he mustered out at the end of his three-year enlistment in August 1864.

Before his enlistment expired, he had been offered a commission. He declined. “I did not choose to remain, it was too hard a life for me,” he remarked.

Years later, at the Grand Army of the Republic meeting, life was not nearly as hard as it had been in 1862. Walking home that raw December night he offered a silent prayer of thanks for a good life and all of the opportunities and honors he had received over the years. He had married a wonderful woman and had two children, whom he adored. He had served as postmaster of Nantucket, town assessor, town clerk and Commander of the Thomas M. Gardner Post 207 of the G.A.R.

In the sunset of his life, Murphey reflected on the role he and his compatriots played during the war, and how he hoped they would be remembered.

“Time will thin the Veteran ranks, as battle thinned the armies of thirty years ago, and each succeeding year will illustrate the mournful record of their mortality. But never so long as Americans love liberty, and honor the precepts of their fathers will America forget her debt to the private soldier who fought with Grant and Sheridan and Sherman with Hancock and Thomas and Meade and to whose courage and fidelity under every trial the country owes its present happiness and peace.”

On May 2, 1931, the ranks of the “Bloody 20th” were thinned by one more when Murphey joined the fallen. He was 88 years old.

References: Henry Livermore Abbott, Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott; George A. Bruce, The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865; A.W. Greeley, Reminiscences of Adventure and Service; Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Touched with Fire: Civil War Letters and Diary of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., 1861-1864; Richard F. Miller, Harvard’s Civil War: A History of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry; Richard F. Miller and Robert F. Mooney, The Civil War: the Nantucket Experience: Including the Memoirs of Josiah Fitch Murphey; George C. Rable, Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!

Scott Valentine is a Contributing Editor to MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.