By Kurt Luther

Last issue, we announced our Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) software, combining technology and community to create a powerful new way to identify unknown soldiers in portraits. We are thrilled that many of you joined us at the Annual Civil War Collectors Show in Gettysburg, Pa., for our public debut. In this column, I describe a case study of how CWPS can augment classic research techniques, including knowledge of 19th century photographers and their work practices, to solve a photo mystery.

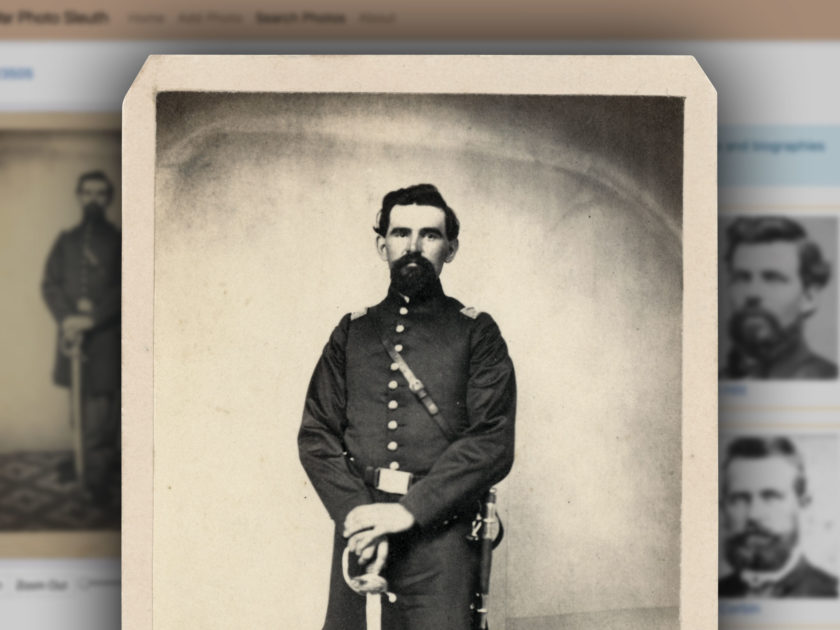

I recently came across a carte de visite of an unidentified company-grade Union officer. Following my usual process, I first made note of the photo’s visual clues, starting with the subject’s uniform and accoutrements.

The carte shows a standing view of a soldier in a dark, well-tailored frock coat with a single row of buttons and shoulder straps with obscured insignia, suggesting a lieutenant or captain. Over the coat, he wears a leather belt with a rectangular belt buckle—probably a standard-issue pattern 1851 eagle belt plate—and a scabbard on his left side, supported by a cross strap. He folds his hands over the pommel of an infantry foot officer’s sword, its blade pointed downwards. If he wore a sash or holster, his forearms obscure it. Trousers of a lighter shade than the coat, and dark shoes, complete the outfit.

The officer’s face is distinctive but well proportioned, with dark hair and eyes, strong brows, a thick mustache and goatee, and large ears. He stands in a studio with a plain backdrop and a patterned floor. His erect posture and steady gaze suggest a quiet confidence.

The officer’s clothing and accoutrements and even the studio all look unremarkable. Without so much as a corps badge, hat insignia, or perhaps a certain painted backdrop or prop, it would be tough to distinguish him from thousands of other line officers who served in the Union Army.

I broadened my inspection of the photo to its mount, searching for other clues. The plain mount has trimmed corners and lacks borders or other decorations that could help date it. The back features a nicely preserved orange 2-cent tax stamp. The photographer had cancelled the stamp in period ink with his initials, E.C., and below them, the date, February 21, 1865. There is no studio back mark, but the front of the mount bears the photographer’s name, E. Codding, in tiny, embossed lettering—a so-called “blind” imprint.

The studio’s location could provide further insight into the soldier’s identity, but it was either trimmed or omitted from mount. The photographer’s surname was fairly unusual, so I was optimistic that I could learn where his studio was based with a bit of research. I turned to my two favorite reference works on Civil War photographers, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West, 1840-1865 (2000) and Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide, 1839-1865 (2005). These books, both written by Peter Palmquist and Thomas Kailbourn, are the definitive biographical dictionaries of photographers operating west of the Mississippi during the Civil War. (Print copies, as is often the case in our field, are rare and expensive, but they are also digitized on Google Books for limited querying.) While many Civil War photographers were based in the east, I’m not aware of an equally comprehensive reference work covering that region of the country.

The Pioneer Photographers books have excellent indices, so it was quick work to look up E. Codding. Only one Codding is listed in either volume: Edgar Codding, daguerreotypist and ambrotypist, born circa 1829. Codding worked in various locations around Iowa, Missouri and Illinois prior to the Civil War. But in the years following, he seems to have settled in Knoxville, in northwest Illinois.

One path forward would be to identify military units linked to Knoxville. The website ILGenWeb conveniently lists the companies recruited in every Illinois county. Fortunately for the Union, but unfortunately for our research efforts, Knox County was apparently a hotbed of patriotic sentiment, with companies from 25 infantry regiments and five cavalry regiments organized there.

A next step would be to search for reference photos of identified Illinois soldiers in online archives, such as the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s Boys in Blue collection or the American Civil War Research Database (HDS), and cross-reference these against the units that originated in Knox County. A search for Illinois soldiers in HDS alone yields over 1,800 photos, and the interface doesn’t allow us to filter these to only the junior officers. We could examine each of these photos for a potential match with the unidentified officer, but this could become a time-consuming process, vulnerable to human error and fatigue, and with no guarantee of success.

Happily, our new Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) software offers a powerful alternative. I entered our mystery photo into the system and tagged the visual evidence: dark-colored frock coat, one row of buttons, indeterminate shoulder straps, Illinois-based photographer. Synthesizing these visual clues, CWPS automatically suggested search filters for Union lieutenants or captains who served Illinois regiments. When I clicked the search button, the software used face recognition to compare the unknown officer to all the identified soldiers matching my search criteria, sorted by similarity. The first result produced an exact match. The entire process took less than a minute.

The matching soldier was Thomas Whiting. Born around 1832 in Connecticut, he married Harriet Pease in Knox County, Ill., in 1857. When the Civil War broke out, he was farmer in Walnut Grove. In August 1862, he joined the newly formed 89th Illinois Infantry as captain of Company G, composed primarily of Knox County men. About a year later, on Sept. 19, 1863, Thomas Whiting fell at the Battle of Chickamauga, one of five officers from his regiment killed at the engagement. His body was eventually shipped north and buried in Center Prairie Cemetery in Knox County.

Whiting’s biography creates a conundrum. If he was killed in September 1863, how could the mystery photo be dated February 1865, almost a year and half later? We know the carte is Whiting—the portraits are identical. And we can be confident the carte post-dates Whiting’s death; in addition to the 1865 cancellation, it also features a tax stamp, first introduced in August 1864.

Pondering this discrepancy, I reexamined the photo. Although I’d already considered the fairly typical subject matter, something about the image quality struck me as unusual. The camera angle looked slightly canted. The shiniest objects, like Whiting’s coat buttons, belt buckle and sword blade, looked blurred or blown out, almost white. And most noticeably, a subtle halo of light at the top of the photo seemed to frame the subject matter. I originally attributed these flaws to an inexperienced or rushed photographer, but the new information about the date discrepancy raised a more interesting possibility. Could this carte be a photographic copy of an earlier image?

Photographic copies often signal a special meaning in Civil War-era imagery. If a soldier wanted to acquire extra copies of his likeness to distribute to new comrades or admirers, he had several options, depending on the format of the original. If he had a carte de visite, the task was trivial; he needed only to ask the photographer to produce more copies from the negative, which most studios retained, with no loss in quality. If he had a hard image like a tintype or ambrotype, the best idea was probably to have a new portrait taken, because the quality of any photographic copy would be inferior to the original.

However, sometimes a new portrait wasn’t possible—namely, when the subject was deceased. The departed’s family may have wanted additional photos as mementos, but did not embrace the Victorian custom of post-mortem photography, or did not have access to the body. In these sad cases, a photographic copy, in which the photographer pointed his camera at the original image and snapped a new version, proved the only realistic option, despite the degradation in quality.

The offset camera angle, gleaming metal and halo effect of the Whiting carte, combined with his service record and the one and a half year gap, all pointed to a photographic copy. Perhaps Whiting originally sat for a tintype shortly after joining the army, and left it with his wife Harriet. When he was killed a year later, this tintype may have been the only visual evidence of his existence. In February 1865, Harriet may have visited Edgar Codding’s studio in Knoxville, about 30 miles from the Whiting farm in Walnut Grove, and requested carte de visite copies for relatives. As Codding photographed the tintype, the reproduction would have created the telltale visual artifacts we see today.

The evidence suggests that Mrs. Whiting made a special effort to preserve her husband’s image and memory after he made the ultimate sacrifice for his country. But as with so many others, the identity of this portrait was lost to time. With careful research methods and new tools like CWPS, we can honor those efforts by recovering the names and stories of soldiers like Capt. Thomas Whiting. They deserve to be remembered.

We encourage you to pick up the torch to continue this investigation and, as always, submit other photo mysteries to be investigated as well as summaries of your best success stories to MI via email. Please also check out our Facebook page, Civil War Photo Sleuth, to continue the discussion online.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.

© 2017 Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.