By John O’Brien

In 1865, the great War for Southern Independence ground to a final end after four and a quarter years of combat and a tremendous cost in blood and fortune. On May 9, victorious Union forces captured President and Commander-in-Chief Jefferson Davis near Irwinville, Ga., as he and his cabinet fled south from the fallen capital at Richmond, Va.

That Davis had to be taken by force was perhaps no surprise, for he had indicated that surrender was not an option. In early 1861, he addressed South Carolina’s Hampton Legion near Manassas, Va., and said, “When the last line of bayonets is leveled, I will be with you.” In July 1864, he told two northern visitors, “This war must go on till the last of this generation falls in his tracks, and his children seize his musket and fight our battles, unless you acknowledge our right of self-government. We are not fighting for Slavery. We are fighting for independence; and that, or extermination, we will have.” His words are reminiscent of those uttered by Winston Churchill in his heralded 1940 speech before the House of Commons, “We shall fight on the beaches … we shall never surrender.”

The never-say-die spirit that carried Davis through the war sustained him through two years as a state prisoner, briefly shackled in chains, at Virginia’s Fortress Monroe. Stripped of his citizenship, he was a man without a country. But, for the next 22 years, he lived in the afterglow of the Lost Cause. He wrote, made speeches and dedicated memorials. In 1881, he completed The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, his defense of secession and the war for Southern independence—and an important text in the Lost Cause narrative.

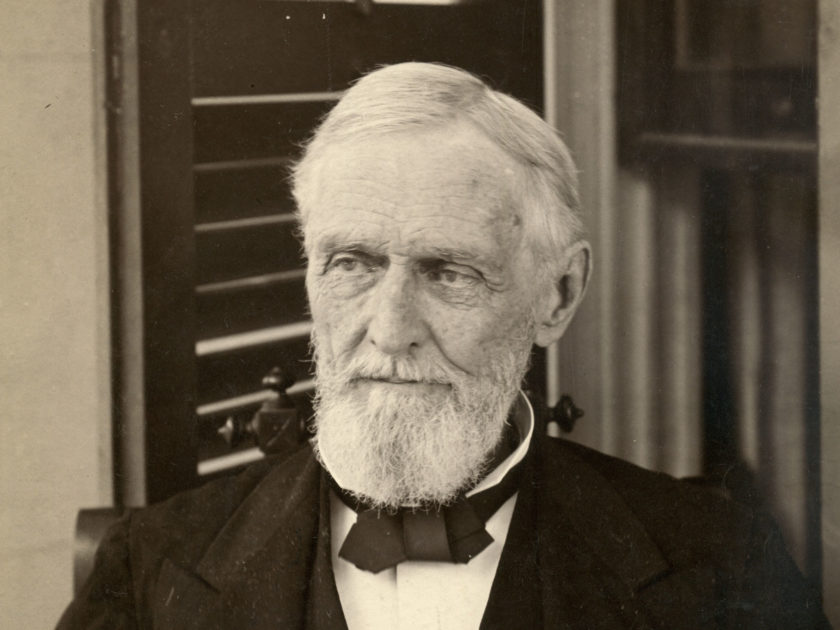

Davis posed for a portrait almost every year after his release from prison in 1867. The relatively high number of sittings stands in stark contrast to the handful of images he had made before and during the war. One explanation may be that the rigors of the presidency and prison caused him to shed his natural shyness, and a concern about an eye noticeably affected by an early bout with malaria. In 1887, he sat for his final portrait in two separate poses. On Dec. 6, 1889, he passed away from a severe cold complicated by malaria and bronchitis at age 79.

His death was widely mourned and marked by the largest public funeral ever held in the South. Distinguished historian Douglas Southall Freeman observed, “Opinions regarding Jefferson Davis always, I suspect, will be divided, because he had such a complex personality. My own belief is that he was a devoted and earnest man of high ability, though he was handicapped by physical malady and a singular sensitiveness to criticism.”

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter restored Davis’ American citizenship.

John O’Brien of Charles Town, W.Va., is a retired journalist and historian from the University of Connecticut, and a contributor to MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.