The wide defensive ditch that reinforced Stockade Redan and its Confederate garrison at Vicksburg, Miss., measured six feet deep and about twice as wide. Akin to a grave, the furrow presented a formidable obstacle for attackers determined to capture a key road to the city.

For 150 Union infantrymen, the trench ultimately became a crucible of suffering and death when they attempted to traverse it on the morning of May 22, 1863.

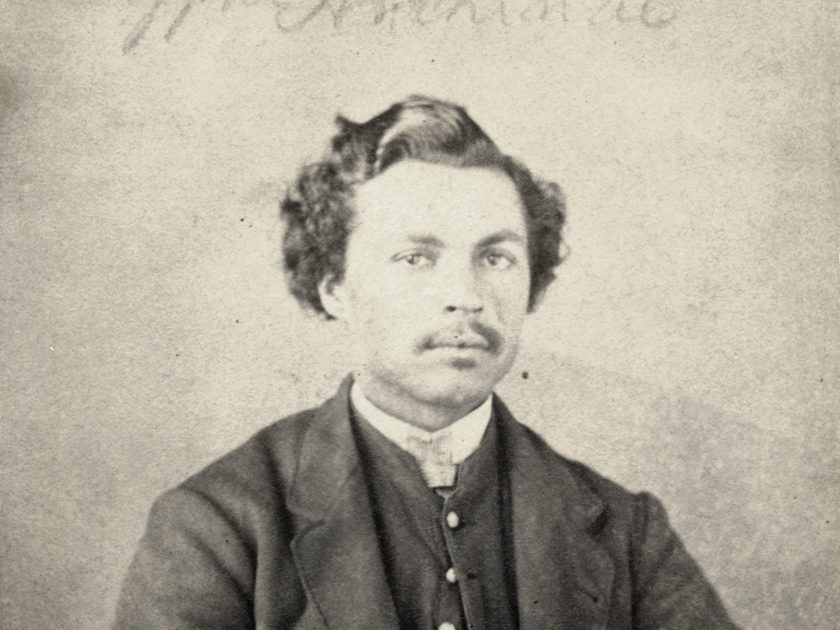

The men, all unmarried, volunteered for a “forlorn hope,” the spearhead of a massive Union assault to capture Vicksburg. The stormers, armed with logs to bridge the ditch, included William J. Archinal, a German-born immigrant who served as a corporal in Company I of the 30th Ohio Infantry.

The men, all unmarried, volunteered for a “forlorn hope,” the spearhead of a massive Union assault to capture Vicksburg. The stormers, armed with logs to bridge the ditch, included William J. Archinal, a German-born immigrant who served as a corporal in Company I of the 30th Ohio Infantry.

Archinal and a comrade, holding opposite ends of one log, crossed open ground near the ditch. A bullet struck his comrade, and he dropped the log. The impact threw Archinal to the ground, where his head struck a stone and knocked him unconscious.

Years later, he recalled what transpired.

“When I came to my senses, I was lying on my face with the log across my body and showers of bullets whistling through the air and dropping all around me. These bullets, I found, came from my own division, and to save myself from being shot by my own comrades, I wriggled from under the log, and got it between me and them. It was providential for me that I did so, for I could hear the bullets striking the log in dozens. Sometime during the afternoon one of our cannon balls struck the log close to my head; the log bounded into the air and fell a little way from me, but I crawled up to it again and hugged it close. The firing continued incessantly all day until nightfall, when it gradually slackened, and finally died away altogether. I thought I could make my way back to the regiment, but as I was rising the butt of my gun which was slung on my back, attracted the attention of the enemy above me. Half a dozen rifles were pointed at me, and I was ordered to surrender, which I did, considering discretion the better part of valor.

When I was taken into the fort, a rebel officer came up to me, slapped me on the shoulder, and said: ‘See here, young man, weren’t you fellows all drunk when you started this morning?’ I replied: ‘No Sir.’ ‘Well, they gave you some whiskey before you started, didn’t they?’ he said, and I answered: ‘No Sir, that plan is not practised in our army.’

‘Didn’t you know it was certain death,’ he asked me again, and I replied: ‘Well, I don’t know, I am still living.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘You are living, but I can assure you that very few of your comrades are.’”

The officer was correct. The stormers had suffered 85 percent casualties in the assault. After the overall attack failed, the Union army opted for a siege that ended less than two months later, when Confederate forces surrendered the city on July 4, 1863, to Maj. Gen Ulysses S. Grant.

Archinal was paroled about 12 hours later and returned to Union lines. He eventually returned to active duty with his regiment, and mustered out of the army in 1865. Almost 30 years later, in 1894, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He was among 96 men recognized for their actions at Vicksburg on May 22, 1863—the highest single-day total in Medal of Honor history.