By Kurt Luther

Identifying a Civil War soldier in an individual portrait can be tricky enough. But for advanced photo sleuths, sorting out multiple soldiers in a group portrait poses unique challenges.

On its face, group identifications require more time and effort because there are more subjects to research and identify. A soldier occupies a particular time and place. Yet, these types of investigations can often progress rapidly because any theory, assumption or insight about one person necessarily impacts the others. Who else occupied a similar slice of history, and why did they choose to immortalize it with a shared portrait? One solid discovery results in constraints and possibilities into which any subsequent identification must fit.

Previous columns have considered group portraits, but this is our first attempt to identify more than one soldier in the same photo. To do so, we will draw on familiar resources, such as reference books and fresh perspectives from fellow collectors. We also take advantage of a new tool, called a concurrent service timeline, which visualizes when soldiers served together to help narrow down possibilities.

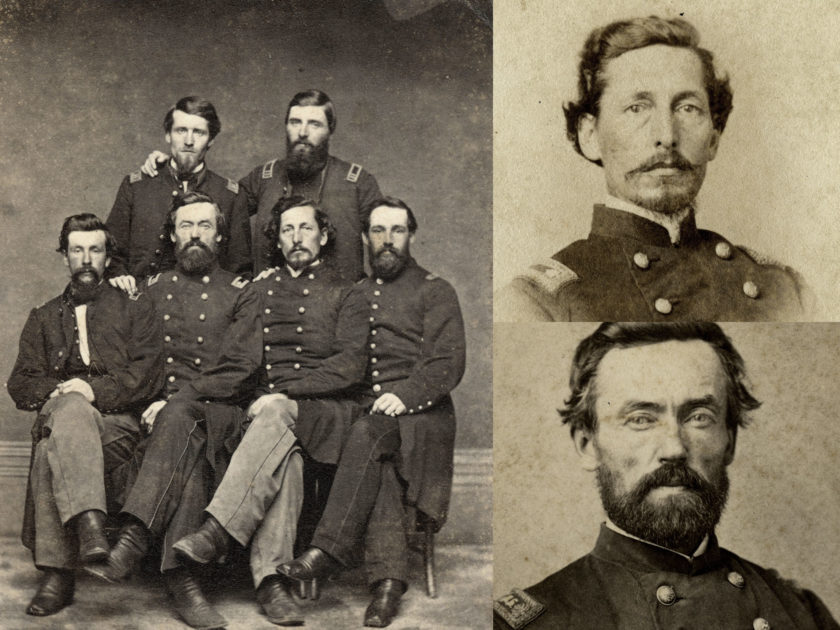

Our case study begins with a carte de visite featuring six unidentified Union officers. The two men occupying the center of the frame are field officers, judging by the double rows of buttons adorning their coats. The man on the left wears the oak leaves of a major, lieutenant colonel, or full surgeon. The man on the right, rather surprisingly, lacks any shoulder straps, allowing for the possibility of any rank between major and full colonel. Surrounding the field officers are four junior officers. The two men standing in the back wear captains’ shoulder straps, while the remaining pair seated in the front row appear to be first lieutenants.

Otherwise, this carte is pretty “cold.” Few additional clues are available. The mount lacks a photographer’s imprint or tax stamp. The officers wear no corps badges or headwear bearing regiment numerals or branch of service insignia. Groupings like this image typically depict a regimental commander and his staff. With this assumption in mind, I began my investigation with the goal of identifying the field officers.

High-ranking officers offer an interesting opportunity for photo sleuths. On the one hand, because they are more rare than the rank-and-file, the pool of candidates should be more manageable. (Theoretically, there are only three field officers for every thousand privates.) On the other hand, with higher rank generally comes better documentation; such prominent men were more likely to appear as engravings in regimental histories and to dole out dozens of cartes de visite. For example, the American Civil War Database (HDS) contains photos of more than 3,500 colonels, but less than 1,300 corporals. The upshot: identifying a field officer guarantees a lot of work, but it’s probably worth trying.

I scanned through all five volumes of Roger Hunt’s Colonels in Blue series looking for a matching face, but had no luck. Moving on to Brevet Brigadier Generals in Blue by Hunt and Jack Brown, I found a familiar face on page 431. John Morrill, colonel of the 64th Illinois Infantry, appeared to be the shoulder strap-less officer in my mystery photo. I didn’t find him in my Colonels in Blue search because the volume featuring Illinois colonels has not yet been published.

As I’ve often emphasized in this column, facial similarity is just a starting point. Was this man really John Morrill? My best chance to confirm this working theory was to use it to identify more officers in the photo. If the details of Morrill’s biography lined up with theirs, then each of the tentative identifications would mutually reinforce the others. If not, then I’d know Morrill registers a false positive, and I’d try another theory.

The concurrent service timeline visualizes when soldiers served together to help narrow down possibilities.

Morrill’s war biography offers some critical details. A gunsmith originally from New Hampshire, he joined the 64th Illinois as captain of Company A in late 1861. One year later, he was appointed lieutenant colonel in charge of all six companies. When four more companies were added in February 1864, Morrill received a promotion to full colonel in recognition of his enlarged command. He led his regiment through the Atlanta campaign until a gunshot wound to the right shoulder took him out of action on July 22, 1864. After a hospital visit and 60 days leave failed to restore the use of his arm, he was reassigned to head a district in the Department of Missouri for the remainder of the war.

Morrill’s multi-year command of the 64th creates a significant time frame in which he may have sat with subordinates for a group portrait. His lack of shoulder straps prevents us from narrowing the window to the time either before or after his promotion to full colonel. With this information in mind, my next step was to determine which officers, given their service histories, could feasibly have appeared with Morrill wearing the ranks pictured in the group portrait. To expand my search, I needed two things: a list of officers who served with Morrill in the 64th Illinois, and a set of reference images of those officers.

To accomplish the first goal, I decided to create a concurrent service timeline for all officers of the 64th. A concurrent service timeline allows us to take information about soldiers’ service records, typically presented in dense tables, and display it visually. This helps us quickly identify time periods when certain soldiers served concurrently (or didn’t).

Using Google Docs, I first made a spreadsheet with a column for every month that Morrill was a field officer, September 1862 through July 1864. I then made a row for every soldier who held a commissioned officer’s rank in the 64th, using the Adjutant General’s rosters hosted online by Illinois GenWeb. For each cell, I filled in the officer’s rank during that month; e.g. Hanson H. Crews was second lieutenant of Company G for February, March, April and May, and first lieutenant in June and July. I also indicated when soldiers resigned or died. The result is available here: https://goo.gl/mk9D6p. Feel free to copy and modify for your own research.

To accomplish my second goal, I gathered together as many reference images of 64th Illinois officers as I could find. HDS provided several, but I hit the jackpot with Boys in Blue, an online photo gallery hosted by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. This collection contains more than 900 digitized portraits of Union soldiers from Illinois—a fraction of the 8,000 such images in the Library’s physical archives, including 56 photos of members of the 64th.

To accomplish my second goal, I gathered together as many reference images of 64th Illinois officers as I could find. HDS provided several, but I hit the jackpot with Boys in Blue, an online photo gallery hosted by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. This collection contains more than 900 digitized portraits of Union soldiers from Illinois—a fraction of the 8,000 such images in the Library’s physical archives, including 56 photos of members of the 64th.

With both goals achieved, I prepared to tentatively identify more officers in the mystery photo. I focused on the field officer to Morrill’s left, who offered the greatest chances for success. The concurrent service timeline showed that there were 68 unique individuals who mustered in as officers at some point in the 64th’s history. Of these, five served as field officers while Morrill led the regiment. When I consulted my reference images for these men, I got two hits. The field officer beside Morrill appeared to be Michael W. Manning. The man standing behind him resembled Joseph S. Reynolds, captain of Company D and a future field commander of the regiment.

Manning’s and Reynolds’ service records significantly narrow the time frame for the group portrait to a six-month period between February 1864, when Manning was promoted from captain to lieutenant colonel, and July 1864, when Morrill was severely wounded. The concurrent service timeline shows that 26 officers (besides Reynolds and Manning) served within this window, and held any of the ranks visible in the group portrait. The names of the remaining three unidentified officers had to be among these 26. I found reference images for 15 of them, but my initial pass hadn’t turned up any obvious matches, other than Reynolds and Manning. Setting my research aside for the moment, I hoped that perhaps some new clue would surface in the future.

I didn’t have to wait long. A few weeks later at a Civil War collectibles show in Gettysburg, I joined a conversation between two men about portraits of the 1st Minnesota Infantry. One of the men, Michael Cunningham, soon revealed that he also collected images of the 64th Illinois—and better yet, he owned a copy of the same group portrait that I had!

Amazed by this serendipitous encounter, we exchanged theories about the mystery photo. We had independently identified Morrill and Manning. I shared my Reynolds identification, and Cunningham shared one that I had missed: Charles I. Conger, the other standing captain. I had initially passed over Conger because my reference image showed him clean-shaven with the exception of a mustache. In the group portrait, he wore a full beard. Cunningham owned a second view of Conger in mid-beard, which helped him spot a resemblance that I had missed.

This experience was educational. Reynolds, Manning and Morrill were quick to identify because they kept consistent facial hair. Conger demonstrated that soldiers with more capricious grooming styles could mislead me. If I had missed Conger, might I have missed someone else?

I returned to the 15 reference photos, this time with laser focus, comparing hairlines, earlobes and eyebrow shapes—everything except facial hair. Sure enough, my efforts revealed another match. Seated besides Manning was 1st Lt. Duncan M. Reid of Company D, sporting a goatee that he conspicuously lacked in my reference image. Cunningham closed the loop by sharing a second view from his collection of Reid with the same goatee.

With five of the six men identified, we can now take a more educated guess about why they sat for this group portrait. My own theory is that these men arranged it while on their veterans’ furloughs, between January and March 1864, perhaps back in Illinois. All five officers had joined the 64th’s original six companies in the first year of the war. The photo may commemorate the regiment’s expansion to 10 companies and Manning and Morrill’s corresponding promotions, perhaps so recent that the latter had not yet acquired new shoulder straps. With arms draped over each other’s shoulders, the officers seem to express a warm familiarity.

The trials ahead would bring them even closer together. Morrill, severely wounded later that year, survived to marry Conger’s sister, Visa, in 1869. Conger would be killed at Resaca on October 18, and buried in the family plot in Illinois. Manning and Reynolds would both command the 64th, while Reid served more than two years as first lieutenant. All three survived the war.

Although the mystery image has yielded many of its secrets, a key question remains: Who is the sixth officer?

I don’t yet have an answer. But some clues offer a path forward. His dark blue pants and coat, which appears to bear general staff buttons and a first lieutenant’s shoulder straps, suggest the uniform of an assistant surgeon. I have not been able to locate any reference images of Henry A. Mix or William D. Plummer, the two assistant surgeons during Morrill’s colonelcy.

Perhaps diligent research by a reader, however, can restore the name of the final soldier, which, in turn, may shed new light on the story behind this group portrait.

We encourage you to pick up the torch to continue this investigation and, as always, submit other photo mysteries to be investigated as well as summaries of your best success stories to MI via email. Please also check out our Facebook page, Civil War Photo Sleuth, to continue the discussion online.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.