By William Morgan-Palmer

By 1865, the bullets had stopped flying and many of the soldiers in blue and gray marched home. But the residual effects of the war would continue for many years.

Although Union veteran John Quincy Dickinson had escaped death on the battlefield, he faced new threats in his assignment to the Freedman’s Bureau in Jackson County, Fla., where he found himself in the crosshairs of the politically charged violence of the reconstruction effort. Yet behind his dutiful courage, he possessed a sober understanding of the imminent danger that he faced.

Born and raised in the small rural village of Benson, Vt., Dickinson graduated from Middlebury College in 1860, and soon thereafter began work as a news reporter for the Rutland Herald. His journalistic career was cut short however, as the call to arms rang out across the Union in 1861.

Dickinson enrolled in the military on Nov. 12, 1861, and mustered into the 7th Vermont Infantry as second lieutenant of Company C on Feb. 12, 1862. While stationed along the Gulf Coast in Louisiana, Alabama and Florida, the 7th saw its share of combat, most notably the capture of New Orleans in 1862. Dickinson rose to the rank of first lieutenant of his company, as well as quartermaster of the 7th. According to the regimental history, he was appointed captain of Company F in 1865, although he never mustered at this rank. He resigned his commission at Brownsville, Texas, in August 1865, because he was “suffering from fever and diarrhea of a malarial character.”

Despite his roots in the North, Dickinson elected to take up residence in Florida after the war, where he and a few associates established and managed a sawmill in the Florida panhandle. Their business ultimately failed, but Dickinson soon after took advantage of the increasing political opportunities that emerged as the nation entered post-war reconstruction.

Dickinson entered another type of war zone when he took his place within the Florida state Republican Party. In 1868, he received an offer to serve as the head of the Marianna Freedman’s Bureau office in Jackson County, which he graciously accepted. The Marianna office was dilapidated, and had been neglected by the previous officers. Dickinson’s responsibilities, other than revitalization of the office, were primarily to strengthen the presence of the Republican Party in Jackson County.

Local Ku Klux Klan members however, stood in opposition to the Republican Party in Jackson County.

Prior to Dickinson’s arrival the Klan’s opposition to the Bureau had largely been limited to verbal threats. The residual Union military presence in the area had served as a defensive buffer for the Reconstruction effort and had staved off politically charged violence that may have endangered the Bureau. But as the military presence in Jackson County steadily decreased, Republican officials became increasingly vulnerable.

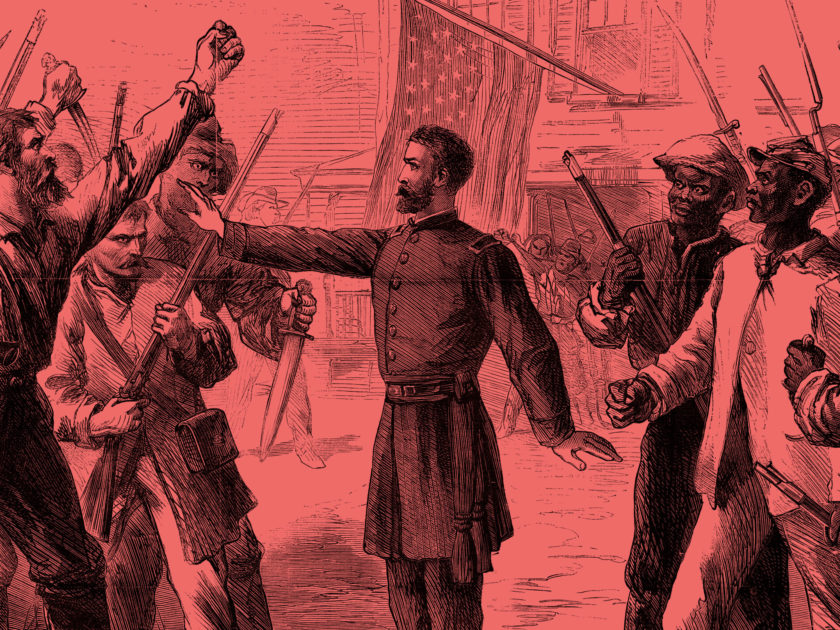

Violence erupted in Jackson County in 1869, as the state election approached. Enraged by the Republican efforts to register and ensure methods for black voters to get to the polls, the Klan violently pursued a number of politically active black citizens throughout Jackson County. On Feb. 26, 1869, Klan members fired upon two of Dickinson’s colleagues, William J. Purman, who was severely wounded, and Dr. John L. Finlayson, who died in the attack. The brazen attacks characterized the new political reality that had taken hold in Jackson County. Suddenly, the Republican label became a target for many throughout the area.

Dickinson’s forceful defense of his fallen colleagues aroused the anger of the white citizens of Marianna, who concealed the identities of the assassins. Following the attack, Dickinson replaced the late Finlayson as the clerk of the court, and became the head of the Republican Party in Jackson County.

The violence persisted, and as the 1870 state election approached, Dickinson found himself the sole white Republican official in Jackson. Party leaders knew they needed to maintain control in the state legislature if they wanted their party to survive in the state. One Republican wrote to Dickinson from the safety of Tallahassee, and reminded him that “all of our hopes for success in Jackson” rested upon him. The letter went on further to single him out as the lone, reliable pillar for the state and party in the area.

Dickinson courageously strove to ensure that black men voted in the 1870 state elections. Nevertheless, violence and intimidation carried the day. At one polling place, a local Democrat attacked black voters with his walking stick, telling them he would “have their blood or guts.” Another white Democrat shouted, “This has been a negro Government, but now it is going to be a white man’s Government. You have been voting for niggers, carpet-baggers, and scalawags, and we white men are going to put a stop to it.”

As a result of the hostility and intimidation, at least 200 black men in the county chose not to vote, and the Republican Party suffered several important losses to the Democrats. In the wake of their success, Democrats in Jackson County increased their threats and violence against black and white Republicans, and the few remaining local white Republicans resigned their offices out of fear for their safety.

Dickinson was racked with depression brought on by the events. “Human life is counted cheap,” he remarked. “The frequency and cold blood which have characterized our murders has not been to me so fearful a fact as the carelessness with which the public learns of a new outrage.”

“I hardly think it possible for me to get through with another election with my head on my shoulders.”

Dickinson wrote to the Florida secretary of state, and reflected upon his political legacy. “To say that the colored man here has through my agency uniformly obtained even-handed justice would be a lie; to say that I have striven, even to a loss of self-respect and several times by incurring personal danger, to do the best thing under the circumstances, is to tell the whole truth.”

Dickinson knew that his life was in danger, and, in March 1871, wrote, “I hardly think it possible for me to get through with another election with my head on my shoulders.” Regrettably, his time would come sooner than he expected.

On the evening of April 3, 1871, while on his way home from a meeting with Jackson County officials, Dickinson was ambushed by a group of assassins who were hiding near his home. The men fired 13 or 14 buckshot rounds at Dickinson from a protected spot behind a cedar tree. The shots pierced his intestines and lungs. One of the gunmen then approached Dickinson’s listless body and shot him through the heart.

News of Dickinson’s death traveled fast across the nation, as newspapers printed starkly different accounts of the story. Southern newspapers sought to discredit the evidence that pointed to the Klan. “Circumstances rather point to a negro as the assassin, for the object was clearly robbery,” wrote the editors of the Raleigh Daily Telegraph. “The fanatical press at the North have seized upon this as another Ku Klux Outrage and they add Mr. Dickinson to the long list of ‘victims of southern hatred.’”

By contrast, Republican newspapers mourned the loss of Dickinson, and refused to acknowledge the likelihood of any other assailant than the KKK. “He had from time to time, owing to him being an earnest republican and a leader of the party in Jackson County, been threatened with death,” wrote the editors of one paper. “But having right and freedom as his motto, bid defiance to his enemies and died at his post; he was a good citizen and officer, and all that could be said against him by his bitterest political enemies, was that he was a Republican.”

Dickinson would be one of the last of about 150 men, both black and white, to die in what became known as the 1869-1871 Jackson County War. In the end, white supremacy and Democratic power won.

In their regimental history, one comrade from the 7th Vermont paid tribute to Dickinson’s sacrifice, “Although he escaped the rebel balls on more than one battle field, he at last fell a victim to rebel hate, which was as unrelenting for years after the war as it was during its progress.”

Sources: William C. Holbrook, A Narrative of the Services of the Officers and Enlisted Men of the 7th Regiment of Vermont Volunteers; Daniel R. Weinfeld, The Jackson County War: Reconstruction and Resistance in Post-Civil War Florida; Compiled military service record of John Quincy Dickinson, National Archives; Raleigh Daily Telegraph, April 25, 1871; Bloomington Daily Pantagraph (Bloomington, Ill.), April 25, 1871.

William Morgan-Palmer is a double major in American Studies and Political Science at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Va. He plans to attend law school.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.