By Kevin D. Canberg

In 1861, happenstance brought together young Carrie Deppen and her soldier love, George W. Ladd.

And, 154 years later, a chance discovery has reunited them.

On Aug. 29, 1862, Ladd, a young New Hampshire soldier, sustained a severe wound during the frenzied fight at Second Manassas. Bleeding profusely from a mangled leg, Ladd was carried from the field to a surgeon’s tent, where the useless leg was removed. Sent to convalesce in a Washington, D.C. hospital, he lingered there for several weeks, until succumbing to the effects of the amputation on Sept. 25. Pvt. Ladd took his last breath at the tender age of 22.

Retribution catalyzed Ladd’s Civil War story. A few weeks prior to his enlistment, Ladd’s first cousin, Luther C. Ladd, lost his life on a Baltimore street when he, and his fellow members of the 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, ran afoul of an armed secessionist mob. With a brickbat to the skull and a ball to the leg, Luther became one of the first casualties of the Civil War. After hearing the terrible news, Ladd joined the fight. “When I heard news of [Luther’s] death, I told my folks I would go and try to revenge [him],” he wrote.

By June 1861, Ladd was drilling with Company B of the 2nd New Hampshire, a company of sharpshooters nicknamed “Goodwin’s Rifles.” Given their prowess at slinging lead, the boys of Company B were issued coveted Sharps rifles and matching saber bayonets, with which to ply their deadly trade.

The 2nd New Hampshire headed by train to Virginia, a few months after organization, Ladd among them. During a stop in Lebanon, Pa., he noticed an attractive girl in the admiring crowd. He quickly jotted his name and regimental designation on a card, and threw it out the window towards the woman, Carrie Deppen. She picked it up just a few moments before the iron wheels resumed to roll towards Washington. The connection made, she began a vigilant correspondence with Ladd that would last until just prior to the fateful day on a Virginia battlefield. They would never be physically closer than the moment the calling card fluttered from Ladd’s hand to her hand.

For 10 months, Ladd wrote Deppen constantly, and with increasing passion. A lover and a fighter in every sense, Ladd described the 2nd’s brutal engagements in Virginia – at First Manassas, Williamsburg and Fair Oaks – alternating his battle narratives with wistful, and occasionally scandalous romance. A series of letters even suggest the two lovers debated sneaking Deppen into the Army, disguised as a man, so that they could be together. “I have read a number of times about girls having enlisted in regts. [Two] were found in Gen. Pope’s army a short time since, who had enlisted with their lovers, but I shouldn’t advise anyone to do that. Rather romantic, is it not?” he wrote. Ladd ended his last known letter to Deppen with, “Much love to you and sweet kisses. Dream of me, love.”

After Ladd’s death, his mother, Susan Abbott, stayed in contact with Deppen, lamenting the loss of her son, yet heartened by the effect the young woman had on him. Ladd may have died young, but at least he knew love.

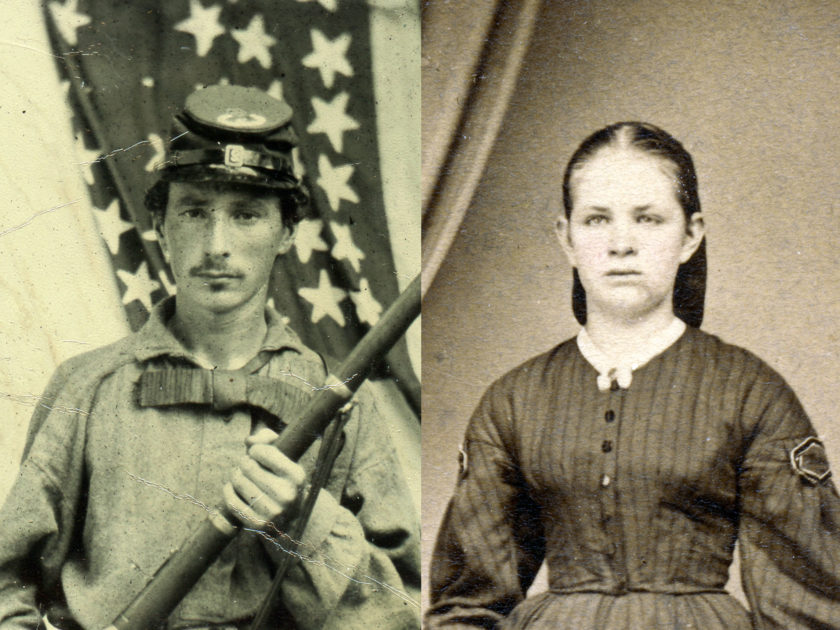

The fascinating story of Ladd and Deppen, preserved in a large archive of period letters and a lone carte de viste photo of Deppen, has always been left partially up to the imagination of the writer. Mike Pride, editor emeritus of the Concord Monitor, explored the young couple’s story in his excellent 2012 book, Our War: Days and Events in the Fight for the Union. In 2004, Deppen’s descendant, Richard R. Lord, told his version of the tale in his Dearest Carrie: The Civil War Romance of a Myerstown Girl and a New Hampshire Boy. While the material breathes life into the story, one significant gap vexed the previous narrators: what did Ladd look like?

For the past nine years, I’ve visited with a dear friend and mentor who taught me almost everything I know about Civil War-era photography. We examined dozens of his images on every visit, a privilege for which I’m humbled and grateful. Several years ago, I opened a tattered leatherette case and inspected an unforgettable sixth-plate Neff’s Patent melainotype. The subject, a young Union soldier, stands in front of a plain backdrop, an American flag draped over the crude studio wall. He grips an 1859 Sharp’s rifle in front of his chest, a light-colored tassel hanging from the stock. His pained expression made me think that he subconsciously used the rifle to try and block the anxiety that comes with deployment. A prop buckle on the soldier’s belt presents the letters “US” as they would correctly be viewed in real life. Tucked into said belt – and maybe an additional cord or sash – sits a revolver. After several years of unabashed image envy, and many rebuffed offers, I finally secured the tintype in a trade.

As soon as I returned home with the image, I went over to my desk to do what I have always done with new images: Carefully disassemble them to inspect for any identifying marks, make a high-resolution scan, and carefully re-package them for safe storage. In this instance, I quickly saw identifying marks etched into the back plate, and two of the brass rails on the keeper with the name “Geo. W. Ladd.” Initial research pointed to several soldiers with the same name, but my high-resolution scan revealed additional key details. Pinned to the soldier’s kepi, within the chinstrap buckle, is a brass “2.” Also, the crown of his forage cap is adorned with the letter “B,” within laurel leaves. Only one Union soldier, the George W. Ladd, fit this bill. And then I learned that Company B of the 2nd New Hampshire received the scarce Sharps rifle. A little more research, and correspondence with Mike Pride, confirmed it. The soldier in my image became the face to the improbable story of Ladd and Deppen.

The photographic artist who used this prop buckle is unknown, but he is thought to have worked in eastern Pennsylvania early in the War, based on known examples with solid identification. This photographer’s images almost always feature this peculiar prop, apparently carved from wood and placed over a soldier’s existing brass buckle. Another common theme is the backdrop, unadorned except for the prominent flag. Most known examples are exceptionally bright sixth-plate Neff’s Patent melainotypes, although I am aware of only one example made on ruby glass.

Ladd ended his last known letter to Deppen with, “Much love to you and sweet kisses. Dream of me, love.”

Based on the above facts, and knowing that the 2nd New Hampshire rode the Reading Railroad line through eastern Pennsylvania en route to Virginia, I can speculate that Ladd had this likeness made during this trip – the very trip he met Deppen. This raises a compelling question: Who ultimately received this image? Was it Deppen?

We may never know. But this image certainly reawakens passions thought extinguished by a war more than 150 years ago.

Kevin D. Canberg, a regulatory compliance attorney specialized in government affairs, studies and collects cased images from the American Civil War era. He also enjoys researching and writing about this period, and has been featured in publications including the Baltimore Sun. Kevin lives in New Jersey with his wife, Sarah, daughter, Darcy, and lovable mutt, Toby.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.