By Edith Cuerrier

One book was a lavish production by the great showman-photographer Mathew Brady for the parlor or library, resplendent with lithographs based on daguerreotypes of young America’s movers and shakers.

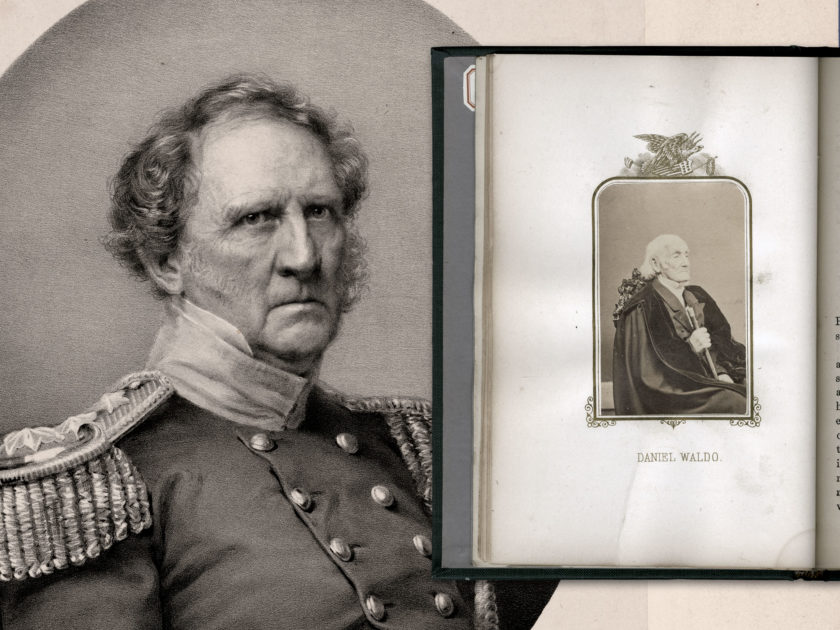

The other edition, a modest affair by an unknown minister, Elias Brewster Hillard, was a small, thin volume of profiles of the last surviving soldiers of the struggle for independence from Great Britain, each illustrated with an original photograph of the grizzled centenarian.

Brady’s 1850 Gallery of Illustrious Americans and Hillard’s 1864 Last Men of the Revolution are examples of biographical books with a tradition that dates back to the 15th century. Steeped in unabashed exceptionalism, each was a product of its time. Both books resulted from the convergence of illustrated and photographically illustrated books— a distinction significant to photographic historians.

Photography Impacts a Nation Consumed with Portraiture

Prior to the advent of photography, American generals, politicians and other notable figures either appeared in public or through drawings or paintings. Once Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the daguerreotype, a unique photographic image captured on a silver-clad copper plate, it became the preferred original from which portraits were reproduced as lithographs or engravings in publications.

In Mirror Image, a volume about the daguerreotype and its influence on American society, author Richard Rudisill explained that in the 19th century there was “a comprehensive effort to characterize the nation” through “national portraiture,” hence the interest in portraits of eminent citizens. Salons of portrait photographs, or portrait galleries, allowed the public to view original photographs of national leaders and celebrities in the form of daguerreotypes. The first establishment of this type in the United States was John Plumbe’s New York Gallery in 1847, followed shortly after by Brady’s Gallery.

The invention of the wet plate collodion negative and the albumen print photographic processes in 1850-51 gave the world a photographic negative-positive capability superior in quality to earlier similar processes. These developments marked the demise of the daguerreotype and the swift ascent of the carte de visite, a calling card-sized portrait more easily mass-produced and affordable.

Brady’s idea of publishing Gallery of Illustrious Americans drawn from his popular physical gallery of daguerreotypes in New York represented a move to capitalize on the public’s interest in celebrities and historical figures. The Gallery embodied the same principles that still permeate the contemporary media, such as the marketing of personality and image commodification. Unfortunately, the idea lacked the significant advantages that photographic prints and cartes de visite had only a few years later: easy reproducibility, portability and low cost.

Photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri patented the carte de visite in France in 1854. But it did not become popular in his country until 1858. England followed suit in 1859-1860, and the format arrived in America late in the summer of 1860. Portraits of military officers, politicians, presidents, authors, artists and other prominent public figures became instant top sellers. According to Dan Younger in “Cartes de Visite: Precedents and Social Influences,” the carte de visite phenomena resulted in profound changes in the “format, style, availability and social exchange of photographic portraiture.” These photographic gems represented the living generation of that time, and, importantly for historians, the nation’s leaders and other public personalities.

The popularity of relatively tiny cartes de visite prints completely altered the size of biographical books, thus explaining the difference between Brady’s large format volume and the small 1864 Hillard book.

Biographical books

In her book on Disdéri, author Elizabeth Anne McCauley cites several early examples of biographical publications about artists and public figures from the 15th and 16th centuries. These precedents illustrate a tradition of books that served common readers as inspiration and motivation by portraying the subjects as heroes. But by the 19th century, this genre of book served less as a platform for hero worship, and more as a useful source of knowledge about people involved in contemporary affairs. Some of these publications were made up of more than one volume, listing people in alphabetical order, and featuring the words ‘dictionary’ or ‘encyclopaedia’ in their titles.

Brady’s idea of publishing Gallery of Illustrious Americans drawn from his popular physical gallery of daguerreotypes in New York represented a move to capitalize on the public’s interest in celebrities and historical figures.

After the introduction of the daguerreotype in 1839, reproductions in the form of lithographs, wood engravings and line drawings based on photographs made the subjects more lifelike, as with the case of Brady’s Gallery, as explained by its editor, Charles Edward Lester, in an article he wrote for the Photographic Art Journal in January 1851. “Before the Daguerrean art was discovered, it is all useless to say that it was within the power of any publisher in the world, or any artist in the world, to execute such faithful, life-like, and strikingly beautiful portraits of our public men.”

A mere decade later however, the much-improved wet plate collodion process allowed actual photographic prints to be used to illustrate publications that include Hillard’s Last Men.

The George Eastman Museum library in Rochester, N.Y., holds several interesting examples of photographically illustrated biographical publications. The Album Contemporain, published in Paris in 1866, contains more than 300 postage stamp size portraits of celebrities, accompanied by short biographical facts. Editor Justin Lallier capitalized on the portrait-collecting trend of the mid-19th century by incorporating portraits of European royalty, military men, artists and eminent public servants.

The addition of actual photographic prints into books remained the only method to include authentic portraits in printed publications until the 1870s. At this time, the halftone process revolutionized printing by reproducing continuous tone images as tiny dots.

The first printed photograph employing the halftone process was an image of Manhattan’s Steinway Hall published in the Dec. 2, 1873, issue of The Daily Graphic, a New York periodical. Perfected by the early 1890s, the process allowed photographs to be mechanically reproduced and incorporated alongside written text in illustrated publications.

A “Great Crossroad of Consciousness”

Gallery and Last Men appeared during a tumultuous time in U.S. history, from the political struggle to expand slavery through the Civil War. Grant Romer, a former conservator at George Eastman Museum (GEM) and resident authority on President Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War era, offered his understanding to provide historical context. In his opinion, both publications were, above all, commercial ventures, though they indeed capitalized on the national identity crisis that dominated the political climate of the day.

Romer likened the country’s tumultuous times to an individual’s adolescence. Born on July 4, 1776, and legitimized in 1789 with the Constitution, the new nation embraced the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. It expanded its territories by purchase and war until 1848, when it became contiguous from coast to coast. Brady’s book was published only two years later.

This rapid expansion was fraught with economic and social upheaval. The nation had arrived at “a great crossroad of consciousness,” as Romer notes. Divided opinions about labor and the balance of power between federal and state governments gradually frayed the fabric of society. Northern reformers, especially abolitionists, challenged the tenets of the Southern way of life. The political rifts in these tensions prompted the secession of Southern states after the election of Lincoln, leading to all-out war in April 1861 after the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

The poisoned climate also abetted the political and military heroes on both sides. The fascination and curiosity that these figures evoked, heightened by nationalistic fervour, provide a useful backdrop for the conception of these books, and the fostering of patriotism.

Gallery: Politically Sensitive, Underlying Patriotism

In Photographing History, author Manuel Komroff qualifies Brady’s Gallery as “an artistic success but a financial failure.” The 12 subjects in the book represent a cross section of the nation geographically and politically. Nine of the men featured include prominent political or military figures: John C. Calhoun, Lewis Cass, Henry Clay, Millard Fillmore, John C. Frémont, Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, Silas Wright and Daniel Webster. These choices perhaps demonstrate an attempt by Brady to appear non-partisan and politically sensitive. Three other prominent figures, naturalist John J. Audubon, theologian William E. Channing and historian William H. Prescott, are less identified with a region or faction of the country.

Though Brady took pains not to take sides in his selections, his overarching loyalties are possibly revealed in the nationalist symbols integrated in the elaborate stamped designs on the front and back cover, which include the words, “The Union Now and For Ever.” The book subtly supports Brady’s perceived role as the official photographer of the entire country.

Last Men: Principles, Patriotism and Union

Rev. Hillard’s volume features six men unknown to Americans. The subjects came to Hillard’s attention in March 1864, after Congress passed legislation to increase the pensions of Revolutionary War veterans, and released the names of 12 veterans believed still alive. Six had passed away before their names became public. Most had passed within two years, and the last died in 1867. Congress eventually recognized one man that Hillard did not visit, Daniel Bakeman, (1759-1869), as the true last survivor of the Revolutionary War. The government was not aware of Bakeman when the 1864 list was issued.

Hillard made it his mission to record their stories for posterity. A graduate of Yale and Andover Theological Seminary, Hillard was the youngest son of a sea captain and farmer who passed his love of sea and travels to his children. According to Archibald MacLeish, the grandson of Hillard, who wrote the introduction of a 1968 reprint of the book, he remembered his grandfather as a strong minded, opinionated, principled and patriotic “man of fire,” with a love of God and “a relish for a good fight in a worthy cause.”

MacLeish also explains that his grandfather was a decided Unionist, as evidenced by his outspoken opposition against Copperheads and other anti-war movements. Hillard’s Union loyalty comes through in the type of questions that he asked of the Revolution survivors in his interviews, such as “What would Washington say…?”

Hillard’s writings reinforce MacLeish’s conclusions. In the first paragraph of Last Men, he refers to the veterans as “sacred.” In the biographical notes, he describes the six pensioners in a way that establishes their affiliation as unionists and/or abolitionists.

Hillard’s obvious pro-Union leanings contrast with Brady’s personal politics, which may be difficult to discern in Gallery.

Whereas Brady’s name is synonymous with Gallery, the person or persons who illustrated Last Men remains something of a mystery. Hillard never credits a photographer by name, though he refers to “artists” who provided albumen portraits of the veterans and lithographs of their homes.

Some speculation surrounds Hillard as the man behind the camera. According to editors Lucien Goldschmidt and Weston J. Naef in the 1980 survey The Truthful Lens, the MacLeish introduction suggests that the reverend was writer and photographer. Goldschmidt and Naef also imply that Hillard produced the photographs, observing that they appear “made uniformly under makeshift circumstances as would have been required if the photographs were made in situ while Hillard visited each for a personal interview.”

Another theory holds that the publishers of Hillard’s book, brothers Nelson Augustus Moore and Roswell A. Moore, were the photographers. Trained photographers, both men operated a studio in Hartford, Conn. Author William Johnson writes in Nineteenth-Century Photography that they were “more probably the makers of the images.”

MacLeish raised a third possibility when he noted that Hillard raced against time as he traveled to the veteran’s homes. He may have engaged the closest available person who owned a camera, which may explain the uneven quality of the portraits.

Whoever took the photographs may never be proven. Still, the likenesses of these aged veterans and their stories reminded Northerners in the midst of the tragedy of the Civil War of the Spirit of 1776. The words uttered by this handful of aged veterans who fought for independence underscored the importance of sacrifice and remembrance.

Epilogue

American photographers recorded the turning points of their fledgling nation and the individuals who shaped its destiny. By the 1850s, those who had signed the Declaration of Independence had disappeared, as did a great many men who were considered national treasures. The few heroes still around from the nation’s early years were well into their elderly years, and photography served as the best modern technology available to preserve their “last living presence,” as Romer put it. Daguerreotypes and, later, albumen prints, immortalized those who had personally helped shape the destiny of the country.

Today, no more than 59 copies of Last Men exist in libraries throughout the United States. Two other copies reside in other countries: Cambridge University in the United Kingdom and the University of Alberta in Canada.

Comparatively, Brady’s Gallery is available in only 15 libraries in America. Only one copy is found outside the United States, at Cambridge. (London’s Victoria and Albert Museum own an incomplete copy.) The low number of surviving volumes could be due in part to the lack of its financial success.

Still, both books remain of great interest to collectors and historians. Numerous history books have included illustrations from Last Men and Gallery through the years.

As time passes and memories of events and people diminish, the preservation of portraiture plays a critical role in the historical record. These images remind us that flesh and blood individuals made our history. A collective debt of gratitude is owed for their achievements and sacrifices on the altar of progress and the furtherance of democracy. Their number rightfully includes Mathew Brady and Elias Brewster Hillard, and those who had the foresight to capture photographic images for future generations.

References: “Cartes de Visite.” American Journal of Photography and the Allied Arts and Sciences 4, No. 12 (Nov. 15, 1861); “Charles Edwards Lester,” Virtualology.com, Museum of History, Hall of North and South Americans; Frank Moore Colby and Talcott Williams, New International Encyclopaedia; “F. D’Avignon Lithographer,” Ancestry.com; Lucien Goldschmidt and Weston J. Naef, The Truthful Lens: A Survey of the Photographically Illustrated Book, 1844-1914; “Gossip.” The Photographic Art Journal. 1, No. 1 (January 1851); George Hobart, Mathew Brady; Dorothy Hoobler, Photographing History: The Career of Mathew Brady; William S. Johnson, Nineteenth-Century Photography: An Annotated Bibliography, 1839-1879; Manuel Komroff, Photographing History: Mathew Brady; Justin Lallier; Album-Contemporain Contenant les Biographies Sommaires de Trois Cents des Principaux Personnages de Notre Époque; Charles Edwards Lester, “M.B. Brady and the Photographic Art.” The Photographic Art Journal. 1, No. 1. (January 1851); Elizabeth Anne McCauley, A.A.E. Disderi and the Carte De Visite Portrait Photograph; Lou W. McCulloch, Card Photographs: A Guide to Their History and Value; Roy Meredith, Mr. Lincoln’s Camera Man: Mathew B. Brady, Mary Panzer, Mathew Brady and the Image of History; Barry Pritzker, “Mathew Brady,” John William Reps, Views and Viewmakers of Urban America: Lithographs of Towns and Cities in the United States and Canada, 1825-1925; Richard Rudisill, Mirror Image: The Influence of the Daguerreotype on American Society; “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans.” The American Whig Review 11, No. 26 (February 1850); Michael Twyman, Printing 1770–1970: An Illustrated History of its Development and Uses in England; “Waifs and Strays: Photographic Eminence,” British Journal of Photography 11, no. 227 (9 September 1864); Dan Younger, “Cartes de Visite: Precedents and Social Influences.” CMP Bulletin 6, no. 4 (1987).

Edith Cuerrier loves historical photography. Her interest began in a high school photography class. After retiring from a career as a military photographer in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), she completed a Masters degree in Photographic Preservation and Collections Management (Ryerson 2009) which included studies at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y. She is currently an archivist at the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.