By Frank Jastrzembski

One summer’s day in 1864, fear gripped the medical director of the 16th Corps when a feisty brigadier threatened to end his life.

The general, Thomas W. Sweeny, was an Irishman and career soldier who had suffered the amputation of an arm after a Mexican War battle wound.

The medical director, Surgeon Norman Gay, incurred Sweeny’s wrath after attempting to commandeer a corps ambulance wagon used by the general’s staff. Gay had a choice to make: Abandon the wagon and escape with his life, or face possible injury or death at the hands of the demonic general.

How Gay, a 44-year-old Vermonter, came to this precarious position traces back to his early years in the Green Mountain State. He was born in 1820 at Gaysville, a bustling community along the White River named after his grandfather, Daniel, and granduncle, Jeremiah, who had settled there and built a factory.

Young Norman’s parents, Dwight and Persis, did not remain in Gaysville. In 1834, when Norman was about 14, the family relocated to St. Lawrence County, situated at the northern corner of New York. Another move, in 1845, ended on a farm in Columbus, Ohio. While his father and his brothers, Justin and Sumner, worked the land, Norman went off to nearby Willoughby Medical College. After graduation in 1847, he became an anatomy instructor at the institution, renamed Starling Medical College.

About the time Dr. Gay embarked on his life’s work, the Hippocratic Oath appeared on the American medical scene. Gay proved his worthiness of it in 1849. During that summer, a vicious cholera outbreak threatened to kill prisoners confined at the Ohio Penitentiary. The inmates died by the dozen—23 in a single day. Five of the most prominent physicians from Columbus, among them Gay, offered their assistance despite the threat posed to their health. The outbreak ended exactly one month later, after taking the lives of 118 prisoners and two physicians.

Gay stepped up again after the Civil War began. In June 1861, he arrived at Camp Chase in Columbus with orders from the state’s Adjutant General, Henry B. Carrington, to take charge of the post hospital. As surgeon in charge, he oversaw the needs of 4,200 or so men waiting to head to the front. He treated a number of patients with various ailments and injuries.

Six months later, Secretary of War Simon Cameron proposed to President Abraham Lincoln that Gay be appointed a brigade surgeon with the rank of major. The recommendation was approved on Christmas Eve 1861, and Gay entered federal service.

Surgeon Norman Gay’s efforts to protect corps ambulances ended with a threat to be horsewhipped and a challenge to a duel.

He reported to the Army of Ohio’s medical director, Dr. Robert Murray, in early 1862. Following the bloodbath at Shiloh, Tenn., on April 6-7, 1862, Murray ordered Gay to oversee one of the hospital depots established in the hills above Pittsburg Landing.

The surgeons were not prepared to handle the 8,000-plus wounded Union soldiers. To further complicate the crisis, heavy rainstorms soaked the battlefield, leaving it a quagmire and making life miserable for the wounded men. Some of the patients were lucky enough to get a bed, while others were made as comfortable as possible on the ground. Though Gay lacked the supplies and manpower for the task, he faithfully toiled day and night to save as many lives as he could.

Six months later, on Oct. 3-4, 1862, Gay treated wounded soldiers following the Battle of Corinth, Miss. By day, he dressed a range of bullet and shell wounds from minor to mortal. By night, he worked by candlelight to operate or supervise amputations and other complex surgeries.

After the federals departed Corinth in pursuit of the enemy, wounded and sick patients were placed in Gay’s charge. Tishomingo Hotel, Corona Female College and other buildings of the Mississippi city were commandeered and converted to accommodate the patients. An agent sent to inspect the hospitals in November, George W. Sturgis, left a positive impression in his report. He judged Gay as “a man eminently qualified by experience and standing.” Likewise, a woman living in the city, Susan B. Gadson, declared the Yankee surgeon as “courteous and kind, and by his polite demeanor, inspired the respect of the few rebels left in the town.”

One high-profile patient Gay examined following the fight at Corinth was Brig. Gen. Richard J. Oglesby of Illinois, who had been shot through the left side under the armpit by a Confederate ball. President Lincoln, an old friend, became anxious after he learned of Oglesby’s wound. On October 8, Lincoln inquired about his condition by telegraph to Oglesby’s superior, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The general reached out to Surgeon John Holston, the Army of the Tennessee’s medical director, for his appraisal. Holston doubted Oglesby would live long, but called in Gay for a second opinion.

Gay examined Oglesby and reported his findings to Holston, who, in turn, contacted Grant’s chief of staff, Maj. John A. Rawlins, with an update. Holston stated, “The doctor agrees with my opinion yesterday. No reasonable hope of recovery.” Convinced Oglesby’s end fast approaching, Holston allowed him to dine on beefsteak and wine laced with opium.

Despite Holston’s and Gay’s unfavorable prognosis, Oglesby defied the odds and lived for another 36 years.

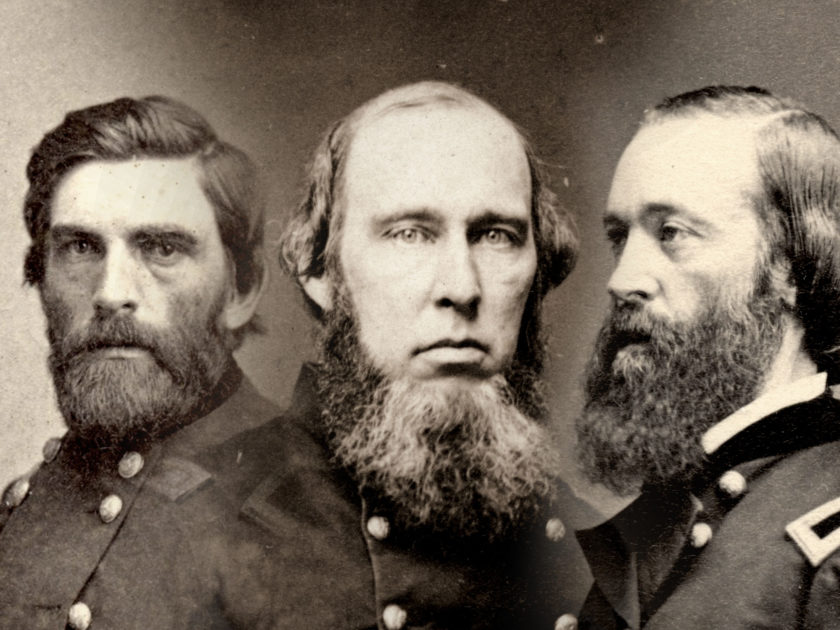

Gay, meanwhile, had become, by July 1863, medical director on the staff of Brig. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, who commanded the 2nd Division of the 16th Corps. Gay soon found himself immersed in a feud between two Union generals—Dodge and Sweeny.

Dodge, a military-educated banker and engineer-surveyor before the war, was not a professional soldier. Still, the 31-year-old had distinguished himself the previous autumn during the Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., where three horses were shot beneath him, and he suffered a wound when a branch from a tree hit by a Confederate shell fell on him. Sweeny, his senior by 11 years, had spent nearly two decades in the army, and had his empty coat sleeve to show for his Mexican War service. He had suffered two more wounds during the Civil War, at the battles of Wilson’s Creek and Shiloh. In the latter engagement, he received praise after he and his brigade successfully defended a gap in the Union lines. But, his dislike of Dodge was palpable.

The ill feelings intensified after the corps was reorganized into two wings, each composed of two divisions. Dodge led the left wing, which included his old 2nd Division, now commanded by Sweeny.

Gay became caught in the crossfire between the quarreling generals in 1864. On January 14, Gay issued an order to his divisional medical chiefs. The order arrived from Dodge’s headquarters without the general’s signature. Sweeny noticed the discrepancy and took the opportunity to snub Dodge. He returned the order with the note stating his division’s surgeon would not obey Gay’s orders. Dodge exchanged choice words with Sweeny, and complained to overall commander Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.

Gay would have an even more peculiar run-in with Sweeny roughly six months later.

In July, Gay learned that Sweeny’s staff officers had seized a corps ambulance. After making this discovery, Gay left to report his findings to Dodge’s headquarters.

Sweeny intercepted Gay before he arrived. He later recalled that he “was most grossly insulted” by the enraged general. Sweeny directed his orderly to beat Gay with his horsewhip. Sweeny then challenged Gay to a duel. As the surgeon made his escape, Sweeny, in a manic-like state, yelled to Gay that he would “shoot me the first time he caught me alone.”

It is unclear if Gay was present or not when the feud between Dodge and Sweeny came to a head. On July 25, 1864, Dodge, in the company of Brig. Gen. John W. Fuller, one of his other division commanders, stopped at Sweeny’s headquarters tent. Sweeny verbally assailed his commander for the events that transpired during the fight at Atlanta three days before.

Dodge, grabbing a quick bite to eat with Fuller that day, was interrupted by the roar of gunfire coming from the direction of Sweeny’s division. He arrived to find Sweeny’s men under a furious Confederate assault. He said Sweeny appeared drunk, so Dodge began to direct his division. This affront infuriated Sweeny.

The confrontation escalated when Sweeny called Dodge a son of a bitch and threw a punch at him. Dodge attacked back, and the two tangled. Staff officers jumped in and broke up the scuffle. Sweeny, still restrained by his staff officers, called out, “Mr. Dodge of Iowa, you can fire a pistol—and so can I!”

Sweeny then turned on Fuller and struck him in his face. The general wrestled Sweeny to the dirt and began to choke the life out of him. Again, staff officers pulled them apart. As Dodge rode away with Fuller, Sweeny cried out, “Go, Mr. Dodge of Iowa, you God-damned political general! I shall expect a note from you, sir!”

Quarrels between generals during the American Civil War were not uncommon, especially in Union armies. One of the more deadly of these incidents took place on Sept. 29, 1862, when Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis confronted Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson in the hall of Louisville’s Galt Hotel, and shot the burly general in the right breast with a Tranter revolver. Despite gunning down and slaying Nelson, Davis was restored to duty and breveted major general.

Sweeny was court-martialed on Dec. 5, 1864. Although ample overwhelming evidence against Sweeny, the Irishman was acquitted. Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, in command of the Army of the Tennessee, refused to allow the exonerated commander to return to his division. Sweeny continued to generate controversy after the war. In the summer of 1866, he was arrested for encouraging the Fenian invasion of Canada.

Dodge remained in command of the 16th Corps until August 19, 1864, when he suffered a head wound that fractured his skull and knocked him unconscious. He had to be carried to the rear on a blanket. He didn’t return to the corps due to the severity of his wound and the complications that followed. After the war, Dodge resumed his career in the railroad industry, and served in the House of Representatives until his death in 1916.

After the fall of Atlanta, Gay oversaw the Marine Hospital in Cincinnati. In July 1865, he mustered out as a lieutenant colonel, ending his eventful career as an army surgeon. He returned to Columbus, continued to practice medicine, and served as a physician at the Ohio Penitentiary.

In August 1885, Gay applied for a veteran’s pension but it was denied. He claimed to be suffering from “blood-poisoning” caused “by accidental inoculation of virus while dissecting an amputated limb” during the war. The Commissioner of Pensions reasoned that Gay’s war service had been voluntary and that he had not acted under orders, “but simply with a view of gratifying his own curiosity and or increasing his store of medical knowledge.”

The eminent physician died at his home in Columbus on May 5, 1898, at the age of 77. He was universally mourned for his altruistic work during and after the war.

“He has done much for the good of his fellowmen and his memory,” the Columbus Medical Journal declared. “He should be hallowed by his successors in the medical profession.”

References: American Medical Times, Nov. 22, 1862, Dec. 20, 1862; Daily Ohio Statesman, Columbus, Ohio, April 21, 1863; The National Tribune, Washington, D.C., Sept. 17, 1885; The Weekly Corinthian, Corinth, Miss., March 31, 1898; Wood County Reporter, Grand Rapids, Wis., Nov. 29, 1862; A Digest of the Laws of the United States, Governing the Granting of Army And Navy Pensions and Bounty-Land Warrants; Decisions of the Secretary of the Interior, And Rulings and Orders of the Commissioner of Pensions Thereunder; Annual Message of the Governor of Ohio, to the Fifty-Ninth General Assembly, at the Session, Commencing Jan. 3, 1870; Anders, “Fisticuffs at Headquarters: Sweeny vs. Dodge.” Civil War Times Illustrated 15 (February 1977); Annual Report for 1871, Made to the Sixtieth General Assembly of the State of Ohio At the Session Commencing January 1, 1872. Part I. “Army Medical Intelligence.” In The Cincinnati Lancet & Observer. Edited by Stevens and Murphy, Vol. 8; Barnes, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865); Brown, History of the Fourth Regiment of Minnesota Infantry Volunteers During the Great Rebellion, 1861-1865; Clark, The Notorious “Bull” Nelson: Murdered Civil War General; DeWitt, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Ohio. Vol. 39; Executive Documents. Message and Annual Reports for 1865, Made to the Fifty-Seventh General Assembly of Ohio, At the Regular Session, Begun and Held in the City of Columbus, January 1, 1866. Part 1; Flint, Austin, ed., Contributions Relating to the Causation and Prevention of Disease, and to Camp Diseases; Together With a Report of the Diseases, Etc., Among the Prisoners at Andersonville, Ga.; Forman, “Ohio Medical History—Pre-Civil War Period: The First Year of the Second Epidemic of Asiatic Cholera in Columbus, Ohio—1849.” Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 53 (October-December, 1944); Franklin County at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century: Historical Record of Its Development, Resources, Industries, Institutions, and Inhabitants; Gay, “Splinters and Dressings for Treatment of Fractures and Injuries of Limbs.” In Transcriptions of the Twenty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Ohio Stated Medical Society. Held at Portsmouth, June 11, 12, and 13, 1872, 253-255; Grace, The Army Surgeon’s Manual, for the Use of Medical Officers, Cadets, Chaplains, and Hospital Stewards; Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Volume 6: September 1-December 8, 1862; Gray, “Corona Female College (1857–1864).” Journal of Mississippi History (May 1980); “January Term, 1883: Knapp v. Thomas.” The Columbus Medical Journal 23 (July to Dec. 31, 1899); Jordan and Thomas, “Reminiscences of an Ohio Volunteer.” Ohio Archeological and Historical Quarterly 48 (1939); Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Ohio, for the Adjourned Session of the Sixty-First General Assembly, Commencing Tuesday, December 1st, 1874. Vol. 71; Loving, “History of Starling Medical College.” The “Old Northwest” Genealogical Quarterly 8, no. 1 (1905); Miner, Past and Present of Greene County, Illinois; Moore, “The Medical Pioneers of Columbus.” Columbus Medical Journal: A Magazine of Medicine and Surgery 20, No. 2 (Jan. 18, 1898); Morgans, Grenville Mellen Dodge in the Civil War: Union Spymaster, Railroad Builder and Organizer of the Fourth Iowa Volunteer Infantry; Official Army Register for 1861; “Obituary—Dr. Norman Gay.” Columbus Medical Journal: A Magazine of Medicine and Surgery 20, no. 1 (Jan. 4, 1898); Plummer, Lincoln’s Rail-Splitter: Governor Richard J. Oglesby; Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Annual Encampment of the Department of Ohio Grand Army of the Republic, Youngstown, O., June 20, 21 and 22, 1899; Reid, Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Generals and Soldiers. Vol. 1; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I—Volume X—In Two Parts. Part I—Reports; Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals.

A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Frank Jastrzembski is an associate editor with Delta Defense, LLC. He studied history at John Carroll University (B.A.) and Cleveland State University (M.A.). He’s written dozens of history and travel articles and two books on Victorian officers. He’s also a regular contributor to the blog Emerging Civil War. He runs “Shrouded Veterans’” a nonprofit mission to identify or repair the graves of Mexican War and Civil War veterans.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.